Roger Vadim was one of the most sensationalistic directors of his day; beginning with the risqué And God Created Woman… (1956), which introduced the world to Brigitte Bardot, each of his films was an event, and, along with his personal life, fodder for the tabloids. Over time, he became best known for his relationships with his starlets. His film work was taken less seriously by critics, as he was swiftly overtaken by the more daring and intellectual directors of the French Nouvelle Vague. Increasingly, his films tended toward camp: these days, he’s still best known for Barbarella (1968), a pop-art, paper-thin fantasy based on the erotic French comic strip that exists largely as a showcase for his then-squeeze, Jane Fonda. Most of his films were about sex, and for that he was unapologetic. I’d imagine film classes now skip Vadim entirely; why show one of his commercial hits when you could be showing a Godard instead? But Blood and Roses (Mourir de plaisir, 1960) deserves to be an exception. Vadim could be a very gifted stylist, and when he had the right subject matter, was capable of remarkable effect. In a year overcrowded with great films, this one is something of a forgotten treasure. And it’s a vampire movie.

Roger Vadim was one of the most sensationalistic directors of his day; beginning with the risqué And God Created Woman… (1956), which introduced the world to Brigitte Bardot, each of his films was an event, and, along with his personal life, fodder for the tabloids. Over time, he became best known for his relationships with his starlets. His film work was taken less seriously by critics, as he was swiftly overtaken by the more daring and intellectual directors of the French Nouvelle Vague. Increasingly, his films tended toward camp: these days, he’s still best known for Barbarella (1968), a pop-art, paper-thin fantasy based on the erotic French comic strip that exists largely as a showcase for his then-squeeze, Jane Fonda. Most of his films were about sex, and for that he was unapologetic. I’d imagine film classes now skip Vadim entirely; why show one of his commercial hits when you could be showing a Godard instead? But Blood and Roses (Mourir de plaisir, 1960) deserves to be an exception. Vadim could be a very gifted stylist, and when he had the right subject matter, was capable of remarkable effect. In a year overcrowded with great films, this one is something of a forgotten treasure. And it’s a vampire movie.

Annette Vadim as Carmilla Karnstein

Vadim had just filmed Les liaisons dangereuses (1959) – based on the 1782 novel by Choderlos de Laclos – with his latest wife, the beautiful Annette Stroyberg. She wasn’t a professional actress, but she longed to be in one of her husband’s films, and so he obliged by giving her the starring role. By the time he began work on Blood and Roses, their marriage was already crumbling; Vadim claimed she was having an affair with a pop singer. If this lends a despondent feeling to the film, it’s only to the story’s benefit. Blood and Roses was based on the famous (and much-filmed) 19th century vampire novella Carmilla. In his 1975 autobiography, Memoirs of the Devil, Vadim writes: “I adore the fantastic. Carmilla, the young vampire in Sheridan Le Fanu’s novel, held a special place in my own personal mythology. I decided to give her Annette’s face. But despite the success of my latest film, persuading a producer and distributors to put their money into a film about a female vampire, to be shot in sunny Italy, in the age of the jet plane and television, was no easy matter. I had a hundred offers of so-called commercial subjects with big stars. They were right, but I could imagine no better role for Annette, and I have never been very good at seeing reason.” He said of Annette Vadim, “[The film] gave its heroine a taste, not for blood, but for freedom.” Their marriage barely lasted to the film’s premiere; his next picture would star Bardot once more.

Leopoldo Karnstein (Mel Ferrer) shares the piano with his cousin Carmilla.

But the melancholy origins of Blood and Roses only enhance the film’s strange qualities. All of its shots of sunny Italy and jet planes, which are, indeed, inappropriate for a Gothic picture, underline the film’s theme of an ancient heritage intruding upon modern day life. Deliberately, there are no scenes borrowed from Hammer’s recent Dracula (1958) – no vampires creeping through windows to seduce young brides; no grisly stakings in mausoleums. Rather than listening to a Van Helsing lecture about the hallmarks of the vampire, we receive clumsy folklore whispered by two gossiping adolescent girls, who drape garlic about their necks when they suspect that vampirism is afoot. It’s parodic – comic relief. Real vampirism is beyond the understanding of the two girls, because it involves adult desires. When a fireworks celebration, for a costume ball at an old abbey, sets off hidden landmines from the war, a previously-hidden crypt is opened, and Signorina Carmilla, exploring, discovers the tomb of her seventeenth century ancestor, Millarca, who was said to be a vampire. In a scene that recalls Mario Bava’s Black Sunday, released the same year, the tomb slides open of its own accord, and something unseen confronts Carmilla. When next we see her, she seems to be possessed by the spirit of Millarca. She develops a craving for blood. Horses are frightened of her, and refuse to let her mount. When she meets a young local girl named Lisa, she stalks her through an orchard, and finally chases her right off a cliff. This killing takes place in the golden hours of dawn, in the gorgeous and lush Italian countryside. Carmilla is a vampire who refuses to waste the daylight, and Vadim has no interest in shooting a film whose visuals aren’t as sweet as candy.

Lisa's corpse is discovered at the bottom of a cliff by a local peasant girl.

Carmilla also begins advancing her relationship with her “first cousin and childhood playmate,” Leopoldo De Karnstein, played by Mel Ferrer (The World, The Flesh, and the Devil). She begins to drive a wedge between Leopoldo and his fiancée, Georgia (the Italian beauty Elsa Martinelli, looking very Sophia Loren-esque): she seduces them both. Granted, neither seduction proceeds further than a kiss, but Vadim lavishes such attention on both encounters that the eroticism is off the scale. Lesbianism? Check. Quasi-incestuousness? Check. But actual sex is withheld – this is a film about taboo temptations. Vadim enjoyed being scandalous (for the press must have something to write about), and so when Carmilla sees her reflection in the mirror – covered in blood where, presumably, she had been staked in a former life – she rips off part of her dress in anger, and collapses semi-nude upon her bed. There is only one brief sequence late in the film which features actual nudity (though not by any of the stars), yet this is a sensual film throughout, embracing the novel’s famous erotic qualities. (A later adaptation, 1970’s The Vampire Lovers, would have license to push the envelope further, though without the lyricism found in Vadim’s film.)

Carmilla kisses a drop of blood off the lips of Georgia (Elsa Martinelli).

A dream sequence climaxes the film, in which Carmilla attempts to possess Georgia. Ostensibly, this is done with a bite on the neck, but that’s not what we see: Vadim subverts the genre convention by showing the possession from Georgia’s point of view, as Carmilla enters her mind. The black-and-white dream sequence – if it can be called that – evokes the work of Jean Cocteau and Luis Buñuel. First we see bright red blood streaking down from the neck of the monochromatic Carmilla – an unsettling but dazzling image. Then the dead Lisa calls to Georgia from the window; she’s swimming in a wall of water. Georgia opens the window and steps forward, directly into the water, her step becoming a dive and a splash. She walks across a courtyard of costumed dancers, and through a tunnel crowded with waiting women and posed female mannequins, until she is seized by nurses and carried into an operating room. There, Carmilla is conducting a surgery upon a topless woman, attended by masked nurses with bloody gloves. She tells Georgia, “I am Millarca. Carmilla is dead. I killed her the night of the ball.” She reveals the face of Carmilla on the operating table. Then Millarca is embracing Georgia, twirling in a black void while a wind howls on the soundtrack, and she bites down on Georgia’s neck. In theory this is pretentious, but damn if it isn’t breathtaking to watch.

In a fantasy sequence, the dead Lisa (Gabriella Farinon), submerged in water, calls to Georgia from the window.

Vadim is ably served by his cinematographer, Claude Renoir (The River, The Golden Coach), and composer Jean Prodromidès, who crafts a theme music for Carmilla that’s both romantic and desolate. The immortal spirit of Millarca narrates the story, and though we receive a psychoanalytical interpretation of the events by a doctor (shades of Psycho‘s denouement), it’s Millarca who has the final word, mocking the diagnosis and urging you to let go of rational explanation. Take her advice.

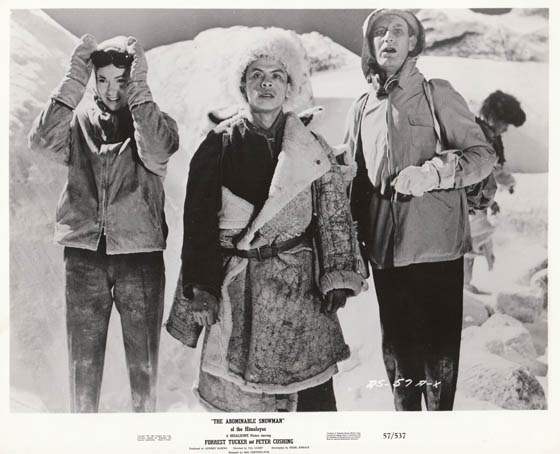

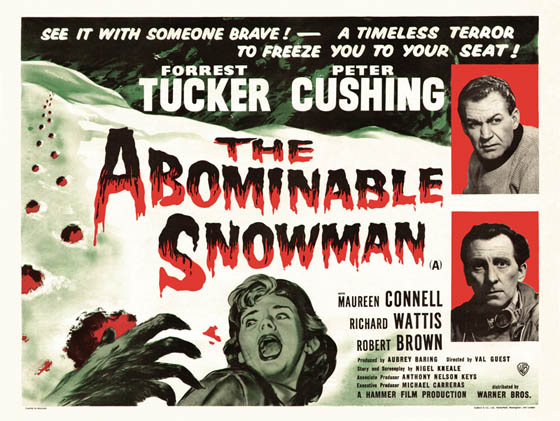

1957 was a landmark year for Hammer Films: The Curse of Frankenstein was released that spring, a full-color adaptation of the Mary Shelley tale with Peter Cushing as the doctor, Christopher Lee as his monster, gooey brains, bright red blood, and a proud “X” certificate. It was full speed ahead into the new world; Dracula (1958), The Mummy (1959), and more than a decade’s worth of sequels would follow. Often overlooked in this explosion of classic horror is The Abominable Snowman, released in the late summer of ’57, following hot on the heels of both The Curse of Frankenstein and Quatermass 2. It could be seen as a transitional film for the studio. The black-and-white, the evolution theme, and the script from Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale, all seem to grant it a kinship to Hammer’s 50’s SF thrillers initiated by

1957 was a landmark year for Hammer Films: The Curse of Frankenstein was released that spring, a full-color adaptation of the Mary Shelley tale with Peter Cushing as the doctor, Christopher Lee as his monster, gooey brains, bright red blood, and a proud “X” certificate. It was full speed ahead into the new world; Dracula (1958), The Mummy (1959), and more than a decade’s worth of sequels would follow. Often overlooked in this explosion of classic horror is The Abominable Snowman, released in the late summer of ’57, following hot on the heels of both The Curse of Frankenstein and Quatermass 2. It could be seen as a transitional film for the studio. The black-and-white, the evolution theme, and the script from Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale, all seem to grant it a kinship to Hammer’s 50’s SF thrillers initiated by

The late 70’s and early 80’s were the golden age of the slasher film, and by that I mean that a lot of slasher films were made – a lot – some of them good (

The late 70’s and early 80’s were the golden age of the slasher film, and by that I mean that a lot of slasher films were made – a lot – some of them good (