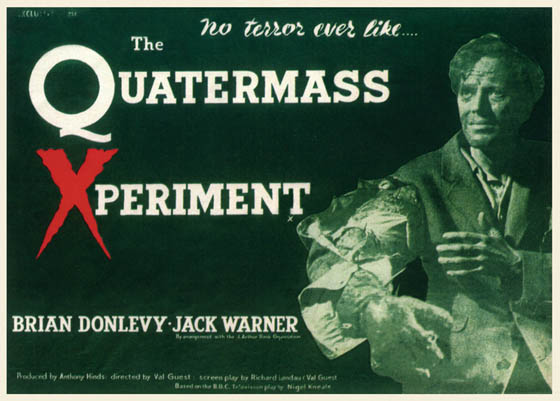

Before there was Doctor Who, there was Professor Quatermass, the British scientist who battled the strangest of alien invasions in the 1953 BBC serial The Quatermass Experiment. The hit science fiction series, starring Reginald Tate as Quatermass, was blessed with an intelligent and suspenseful script by Nigel Kneale, and Hammer Films swooped in and purchased the rights before all the episodes had aired. It was one of the smartest moves the company ever made. Prior to making the film, Hammer was a reliable producer of dispensable B-pictures: detective thrillers, film noirs, comedies. Robert Lippert, the American producer behind countless B-Westerns as well as 1951’s Cesar Romero-plus-dinosaurs picture Lost Continent, had begun co-producing pictures for Hammer, which allowed American stars to be cast, and thus American distribution secured. Their adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s popular serial was part of this arrangement, and so an American, Brian Donlevy (Kiss of Death), was quickly slated for the starring role of Professor Quatermass. This would be the studio’s first picture to be branded with the U.K.’s newly-created “X” rating, meaning that no one under the age of 16 could see the film. Studio head James Carreras and producer Anthony Hinds decided to embrace the rating. The title would be changed to The Quatermass Xperiment, with the giant-sized “X” dominating the posters. The tactic worked, and audiences flocked to the film’s opening.

Before there was Doctor Who, there was Professor Quatermass, the British scientist who battled the strangest of alien invasions in the 1953 BBC serial The Quatermass Experiment. The hit science fiction series, starring Reginald Tate as Quatermass, was blessed with an intelligent and suspenseful script by Nigel Kneale, and Hammer Films swooped in and purchased the rights before all the episodes had aired. It was one of the smartest moves the company ever made. Prior to making the film, Hammer was a reliable producer of dispensable B-pictures: detective thrillers, film noirs, comedies. Robert Lippert, the American producer behind countless B-Westerns as well as 1951’s Cesar Romero-plus-dinosaurs picture Lost Continent, had begun co-producing pictures for Hammer, which allowed American stars to be cast, and thus American distribution secured. Their adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s popular serial was part of this arrangement, and so an American, Brian Donlevy (Kiss of Death), was quickly slated for the starring role of Professor Quatermass. This would be the studio’s first picture to be branded with the U.K.’s newly-created “X” rating, meaning that no one under the age of 16 could see the film. Studio head James Carreras and producer Anthony Hinds decided to embrace the rating. The title would be changed to The Quatermass Xperiment, with the giant-sized “X” dominating the posters. The tactic worked, and audiences flocked to the film’s opening.

A publicity still emphasizes the film's theme of scientists battling a confounding menace.

It’s widely known that Kneale hated the casting of Donlevy, who played the professor with a short temper, at times almost bullying the British scientists and police inspectors around him. Director Val Guest found the actor a commanding presence. Yes, Donlevy’s Quatermass is abrasive when first we meet him, but he probably has to be – taking charge of an accident site where an experimental rocketship (the “Quatermass 1”) has crashed nose-first into the earth. A crowd of onlookers swarm the grounds, and the police and firefighters only add to the chaos. In short order, Quatermass orchestrates a manner of opening the ship without threatening the lives of those inside. It’s an oddly gripping scene, in part because of Guest’s intelligent decision to shoot the film with the immediacy of a docudrama, and in part because of Donlevy. Yes, he is a foul-tempered American, but he subtly dials down his performance as the film continues, the stakes are raised, and the challenge grows more daunting. There’s only one survivor on the “Quatermass 1,” Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth), and since he seems unable to speak, there’s no explanation forthcoming for what happened on the journey, nor where the bodies of his fellow crew members went. Essentially, this is a science fiction mystery – something which was relatively new to the genre. Quatermass is our Sherlock Holmes, though he doesn’t tackle the problem alone: he teams with Police Inspector Lomax (Jack Warner) as they begin to piece together the events which occurred in outer space, and what is happening now to poor Victor.

Publicity still: Richard Wordsworth as the mute, and mutating, Victor Carroon.

Victor’s flesh begins to look sickly and grotesque. At the insistence of his wife Judith (Margia Dean), he’s transferred out of the government laboratory and into a hospital; Quatermass can hardly protest the decision, since they’re unable to diagnose his condition, and he appears to be decaying before their eyes. But once Victor is in the less-protected hospital ward, Judith hatches a plan to liberate her husband and take him home; this backfires when Victor, now absorbing the properties of a cactus which he has punched in his hospital room, murders Judith’s friend and escapes into the streets. This initiates the second act of the film, which recalls James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) – the very property which would be the studio’s next big success. Victor (named after Frankenstein’s creator?) even has an encounter with a young girl by a river, though the girl escapes unharmed (not so her little doll, which receives a swift decapitation). When the astronaut stumbles into the city zoo after closing hours, the end result is animal slaughter – and further mutations, until Victor no longer resembles something human. At last, as Quatermass and Lomax realize that the entire planet could be threatened by the alien entity which has taken control of Victor’s form, they join the British army at Westminster Abbey for a final confrontation.

"The Quatermass Xperiment" was released in the U.S. as "The Creeping Unknown."

Shorn of four minutes, the film was released in the United States as The Creeping Unknown. Hammer had such a hit that the studio seemed to refocus its efforts immediately upon this new science fiction-meets-horror goldmine. The follow-up, though not a sequel, was X the Unknown (1956), written by a young Jimmy Sangster, who would go on to become one of the studio’s most prolific screenwriters. Again, the “X” was displayed prominently in the title, like a boast. (One gathers that if the xylophone were a more fearsome instrument, Hammer would have commissioned a script on the subject.) In X the Unknown, the menace was a radioactive slime bubbling up from a fissure in the Earth’s crust; Leo McKern co-starred, though another American scientist, Dean Jagger, topped the bill. Quatermass 2 (1957 – released in the U.S. as Enemy from Space) reunited Val Guest, Brian Donlevy, and screenwriter Nigel Kneale for a true sequel to Hammer’s blockbuster; but after The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and the subsequent pursuit of straight horror over science fiction thrills, it would not be until 1968 that Professor Quatermass returned to the big screen. And that one would be a stunner: Quatermass and the Pit (in the U.S., Five Million Years to Earth), a nail-biting genre-blender that begins as Satanic horror and evolves gradually into high-concept science fiction (John Carpenter has frequently cited it as one of his favorite films). Andrew Keir would play the Professor with a very different temperament than Donlevy: his Quatermass was moody, cerebral, and brilliant. As a further bonus, he was actually British. Kneale was pleased.

Note: Icon Films in the U.K. has just released a string of Hammer films on budget DVDs: “The Dick Barton Trilogy” (three “Dick Barton” mysteries from the late 40’s and early 50’s), “The Quatermass Double Bill” (The Quatermass Xperiment/Quatermass 2), X the Unknown, The Abominable Snowman, and Captain Kronos Vampire Hunter. It appears that Icon has taken very little care with these releases. For this review I watched the Icon copy, and found it acceptable if not spectacular; however, X the Unknown is a complete botch, as a loud hum overwhelms the sound and dialogue for the entire length of the film. I had to fiddle with my receiver’s sound presets before I could find a mix that would at least reduce the hum a little bit. Reportedly, Captain Kronos is also too dark; I already have the Region 1 copy of this title so I can’t attest to the R2 version’s qualities or lack thereof. (I’ve yet to watch Icon’s DVDs of The Abominable Snowman and Quatermass II, though I will be doing so shortly. I hear The Abominable Snowman is fine, and I hope so, as it’s one of my favorite Hammers.) It’s a shame to see these classic films given such a shoddy treatment; one wishes that Criterion would consider releasing an Eclipse box set of Hammer’s science fiction titles so that at least we have some watchable transfers of the films back in print.

Note: Icon Films in the U.K. has just released a string of Hammer films on budget DVDs: “The Dick Barton Trilogy” (three “Dick Barton” mysteries from the late 40’s and early 50’s), “The Quatermass Double Bill” (The Quatermass Xperiment/Quatermass 2), X the Unknown, The Abominable Snowman, and Captain Kronos Vampire Hunter. It appears that Icon has taken very little care with these releases. For this review I watched the Icon copy, and found it acceptable if not spectacular; however, X the Unknown is a complete botch, as a loud hum overwhelms the sound and dialogue for the entire length of the film. I had to fiddle with my receiver’s sound presets before I could find a mix that would at least reduce the hum a little bit. Reportedly, Captain Kronos is also too dark; I already have the Region 1 copy of this title so I can’t attest to the R2 version’s qualities or lack thereof. (I’ve yet to watch Icon’s DVDs of The Abominable Snowman and Quatermass II, though I will be doing so shortly. I hear The Abominable Snowman is fine, and I hope so, as it’s one of my favorite Hammers.) It’s a shame to see these classic films given such a shoddy treatment; one wishes that Criterion would consider releasing an Eclipse box set of Hammer’s science fiction titles so that at least we have some watchable transfers of the films back in print.

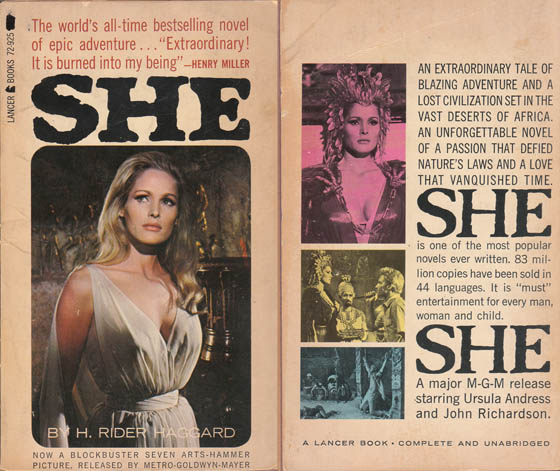

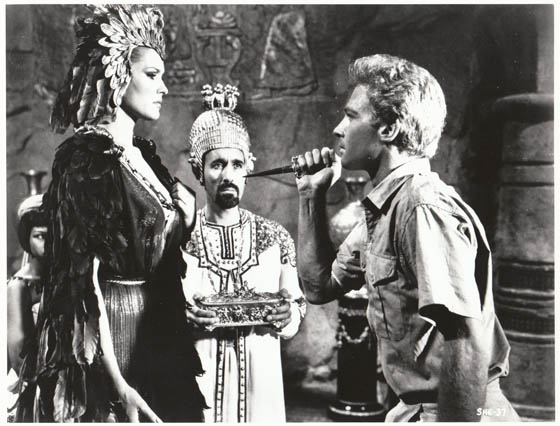

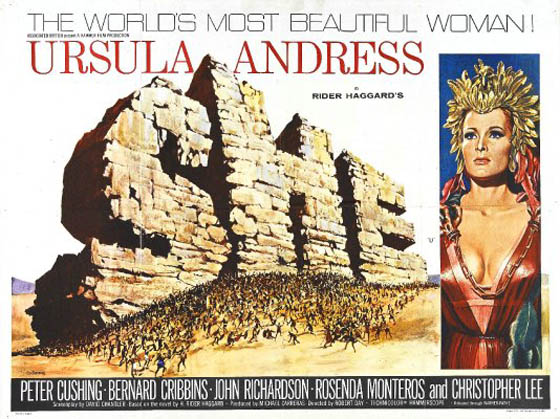

Hammer Films had grown steadily since the box office breakthroughs of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). Distributors knew that the British studio’s genre product was reliably classy and literate, but also sexy and violent; they certainly knew how to fill seats and please audiences. By the mid-60’s, Hammer producers Michael Carreras and Anthony Hinds were ready to swing for the fences: a Hollywood-style spectacle, with a bigger budget than the thrifty studio would typically allow. Hammer settled upon a known property, H. Rider Haggard’s popular adventure novel of 1887, She. As Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes recount in The Hammer Story, it actually took a few years before the studio could enlist an American partner for what promised to be an expensive venture: MGM finally stepped up when Universal would not, and She was ultimately filmed for £323,778, far above the price tag for the typical Hammer programmer. It was shot in the studio’s anamorphic “Hammerscope,” capturing the wide desert landscapes of Israel (the film is set in Palestine, relocating the African setting of Haggard’s original). Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, the studio’s horror stars, both took supporting roles, but overshadowing their presence was Ursula Andress, Dr. No‘s Honey Ryder, in the starring role of the immortal Ayesha, “She Who Must Be Obeyed.” The posters proudly proclaimed her “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman!” above the three towering letters, S-H-E, built out of stone Ben Hur-style. Everything about this movie was going to be big, in the grand Cecil B. DeMille tradition.

Hammer Films had grown steadily since the box office breakthroughs of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). Distributors knew that the British studio’s genre product was reliably classy and literate, but also sexy and violent; they certainly knew how to fill seats and please audiences. By the mid-60’s, Hammer producers Michael Carreras and Anthony Hinds were ready to swing for the fences: a Hollywood-style spectacle, with a bigger budget than the thrifty studio would typically allow. Hammer settled upon a known property, H. Rider Haggard’s popular adventure novel of 1887, She. As Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes recount in The Hammer Story, it actually took a few years before the studio could enlist an American partner for what promised to be an expensive venture: MGM finally stepped up when Universal would not, and She was ultimately filmed for £323,778, far above the price tag for the typical Hammer programmer. It was shot in the studio’s anamorphic “Hammerscope,” capturing the wide desert landscapes of Israel (the film is set in Palestine, relocating the African setting of Haggard’s original). Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, the studio’s horror stars, both took supporting roles, but overshadowing their presence was Ursula Andress, Dr. No‘s Honey Ryder, in the starring role of the immortal Ayesha, “She Who Must Be Obeyed.” The posters proudly proclaimed her “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman!” above the three towering letters, S-H-E, built out of stone Ben Hur-style. Everything about this movie was going to be big, in the grand Cecil B. DeMille tradition.

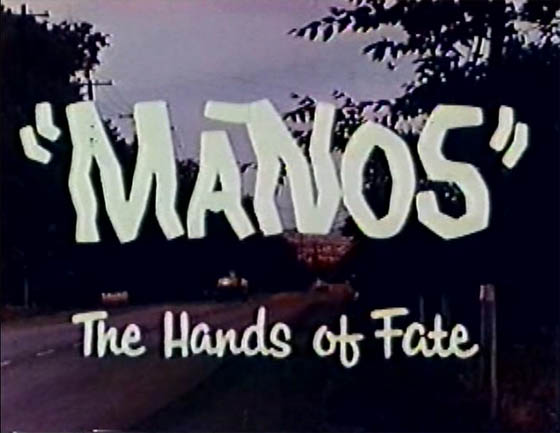

Like almost everyone else, I first saw Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) on Comedy Central’s Mystery Science Theater 3000, probably on one of its reruns. My strongest memory of that first viewing was of women in diaphanous gowns and giant white underwear wrestling to get the attention of their pasty-faced cult leader, The Master (Tom Neyman). Even with the witty riffs of Joel Hodgson and the ‘Bots, you get a queasy feeling watching Manos. It might be the light-jazz soundtrack, or the out-of-focus visuals, or the shaking camera, but there’s a too-many-Quaaludes sensation to the film that’s hard to shake. At first, the film is unintentionally hysterical. After a while, you want to crawl up the wall – anything to escape its deadly pull. I’ve never much liked awarded titles such as “the worst movie ever made.” I’ve made the worst movie ever made, when I was in high school, with a camera rented out from the A/V department; or maybe you did. Narrow the standards to anything that’s seen a theatrical release, and you could still fill warehouses with unwatchable films, far worse than Gigli or Catwoman. But then you’re in the middle of Manos: The Hands of Fate – lost, adrift – and damn if this doesn’t feel like the worst. It’s just so punishing, so thoroughly incompetent, so greatly misguided…so intent on your absolute destruction.

Like almost everyone else, I first saw Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966) on Comedy Central’s Mystery Science Theater 3000, probably on one of its reruns. My strongest memory of that first viewing was of women in diaphanous gowns and giant white underwear wrestling to get the attention of their pasty-faced cult leader, The Master (Tom Neyman). Even with the witty riffs of Joel Hodgson and the ‘Bots, you get a queasy feeling watching Manos. It might be the light-jazz soundtrack, or the out-of-focus visuals, or the shaking camera, but there’s a too-many-Quaaludes sensation to the film that’s hard to shake. At first, the film is unintentionally hysterical. After a while, you want to crawl up the wall – anything to escape its deadly pull. I’ve never much liked awarded titles such as “the worst movie ever made.” I’ve made the worst movie ever made, when I was in high school, with a camera rented out from the A/V department; or maybe you did. Narrow the standards to anything that’s seen a theatrical release, and you could still fill warehouses with unwatchable films, far worse than Gigli or Catwoman. But then you’re in the middle of Manos: The Hands of Fate – lost, adrift – and damn if this doesn’t feel like the worst. It’s just so punishing, so thoroughly incompetent, so greatly misguided…so intent on your absolute destruction.