Heavy Metal magazine debuted in the U.S. in the spring of 1977 with the image of a pointy-breasted robot bashing to pieces another robot with a wrench. The publishers of the National Lampoon had compiled this “adult illustrated fantasy magazine” primarily from the contents of the French Metal Hurlant (“Screaming Metal”), which had already been going for several years and had become a phenomenon in Europe. That magazine was published by Les Humanoides Associes, an organization fronted by artists Philippe Druillet and Jean Giraud (aka “Moebius”), writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, and Bernard Farkas. The comics in Metal Hurlant were typically stream-of-consciousness, erotic, violent, grotesque, and gorgeous. Heavy Metal editors Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant translated and serialized the best of the Hurlant stories, adding into the mix prose from noted science fiction and fantasy authors (Terry Brooks in the first issue, and later James Tiptree, Jr., Theodore Sturgeon, and even Steven Spielberg, excerpting his novelization of Close Encounters of the Third Kind), as well as comics from well-known American artists like Richard Corben and the recently-deceased Vaughn Bodé. Heavy Metal arrived at the right time. Star Wars was released that spring, and science fiction was the rage, but this magazine went to places George Lucas could never go: it was druggy, taboo-flaunting, funny, and oversexed. It was a hit.

Heavy Metal magazine debuted in the U.S. in the spring of 1977 with the image of a pointy-breasted robot bashing to pieces another robot with a wrench. The publishers of the National Lampoon had compiled this “adult illustrated fantasy magazine” primarily from the contents of the French Metal Hurlant (“Screaming Metal”), which had already been going for several years and had become a phenomenon in Europe. That magazine was published by Les Humanoides Associes, an organization fronted by artists Philippe Druillet and Jean Giraud (aka “Moebius”), writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, and Bernard Farkas. The comics in Metal Hurlant were typically stream-of-consciousness, erotic, violent, grotesque, and gorgeous. Heavy Metal editors Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant translated and serialized the best of the Hurlant stories, adding into the mix prose from noted science fiction and fantasy authors (Terry Brooks in the first issue, and later James Tiptree, Jr., Theodore Sturgeon, and even Steven Spielberg, excerpting his novelization of Close Encounters of the Third Kind), as well as comics from well-known American artists like Richard Corben and the recently-deceased Vaughn Bodé. Heavy Metal arrived at the right time. Star Wars was released that spring, and science fiction was the rage, but this magazine went to places George Lucas could never go: it was druggy, taboo-flaunting, funny, and oversexed. It was a hit.

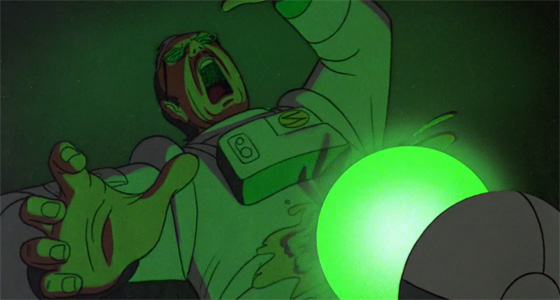

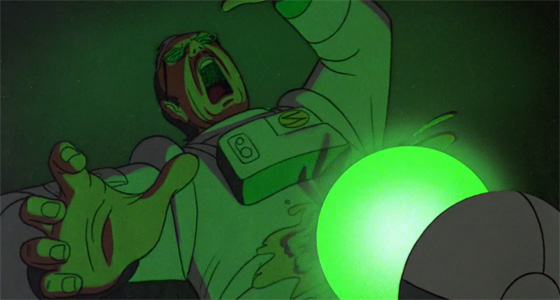

"Grimaldi": an astronaut's gift to his daughter turns out to be murderous.

Soon talks began on a big-screen adaptation, an animated anthology film. The producer would be the same man who’d produced National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978), as well as some of fellow Canadian David Cronenberg’s early films: Ivan Reitman. Each segment of the film – some of which were based upon Heavy Metal stories, others original – would be animated by a different independent unit, all of them working simultaneously to complete the film for director Gerald Potterton. Thus, Heavy Metal the movie has some of the same qualities of the magazine: an anthology that serves up one unique style after another; if one isn’t to your taste, you only need to wait a short while before the next is queued up. Given the title, it would be a requirement to line up a stellar soundtrack, and although most of the bands don’t represent “heavy metal,” they do represent 1981 pretty well: Devo, Cheap Trick, Sammy Hagar, Black Sabbath, Blue Oyster Cult, Donald Fagen, Stevie Nicks, Journey, Nazareth, Grand Funk Railroad, etc. Two soundtrack albums were released – one for the songs (it peaked at #12 on Billboard), and one for Elmer Bernstein’s superb and muscular score; Devo’s end-credits “Working in a Coal Mine” cover was released as a 7″ single bearing the Heavy Metal promo artwork. The R-rated animated film, laden with bare breasts and gore, was unleashed in August of 1981, and became a head-trip favorite for the midnight movie crowd over the next decade or so. It would have to be: entanglements with the music rights kept the film unavailable on video until after it made a theatrical relaunch on its 15th anniversary in 1996. Prior to that, most of its fans had just seen the film on late-night cable. (A Blu-Ray special edition was recently released.)

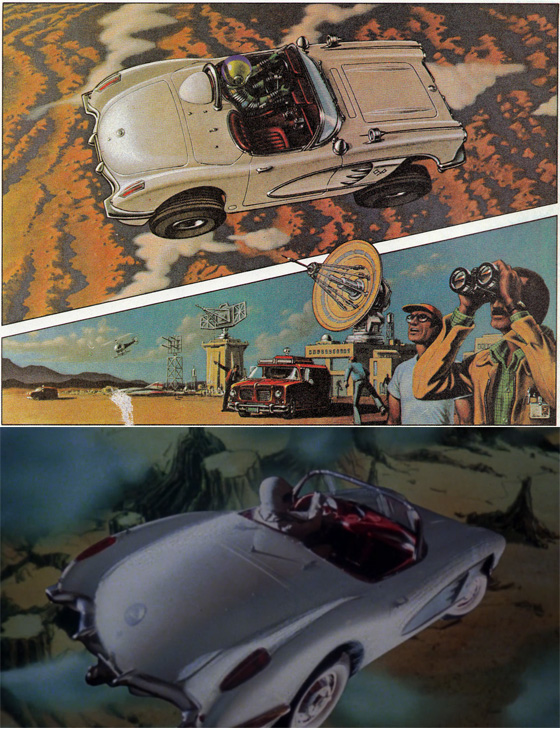

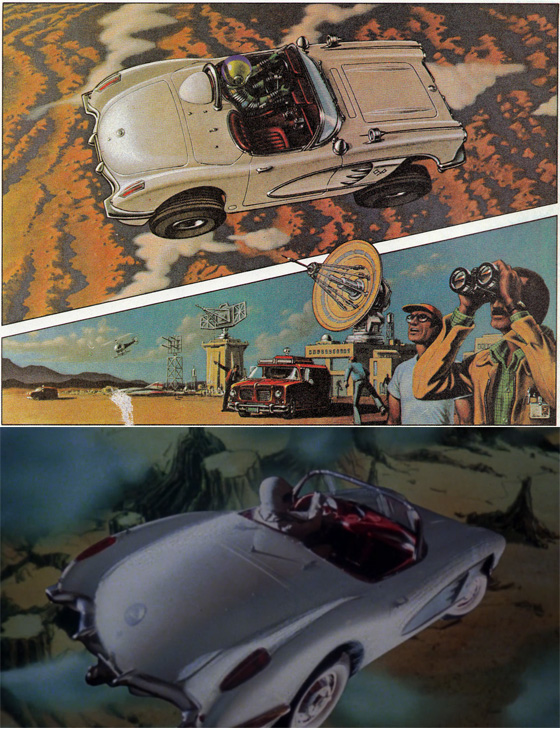

"Soft Landing": the short comic by Dan O'Bannon and Thomas Warkentin (top) was adapted closely for the film (bottom).

The film opens with a space shuttle floating through outer space. The cargo doors open, and out drops a white Corvette convertible, an astronaut at the wheel. The propulsive song “Radar Rider,” by Riggs, blasts on the soundtrack as the car is piloted toward Earth, burning through the atmosphere, hovering over the plains of a desert, and finally firing a parachute to land on all four wheels. This animation style won’t be repeated in the film: a series of photographs rotoscoped imaginatively and finally integrated into traditional cel animation as we transition from this first segment (based on a 1979 comic illustrated by Thomas Warkentin and written by Alien‘s Dan O’Bannon) into “Grimaldi,” which will act as the linking sequence for all of the film’s tales. The astronaut is the father to a young girl in a country farmhouse. He offers her a present, but when he opens the package, inside is a glowing green orb which immediately melts him into goop. This orb is our narrator, who is evil. He will tell the child tales of his cosmic influence before he destroys her. It’s not the strongest story arc: most of these stories are actually about good triumphing over evil (the omnipresent green orb), which makes you wonder why the orb would choose to tell them. (“Oh, I should tell you about this other time that I was defeated…don’t worry, this one also has boobs.”) “Grimaldi” was actually a last minute substitution for a more surrealistic linking device, storyboards of which are shown on the DVD and Blu-Ray.

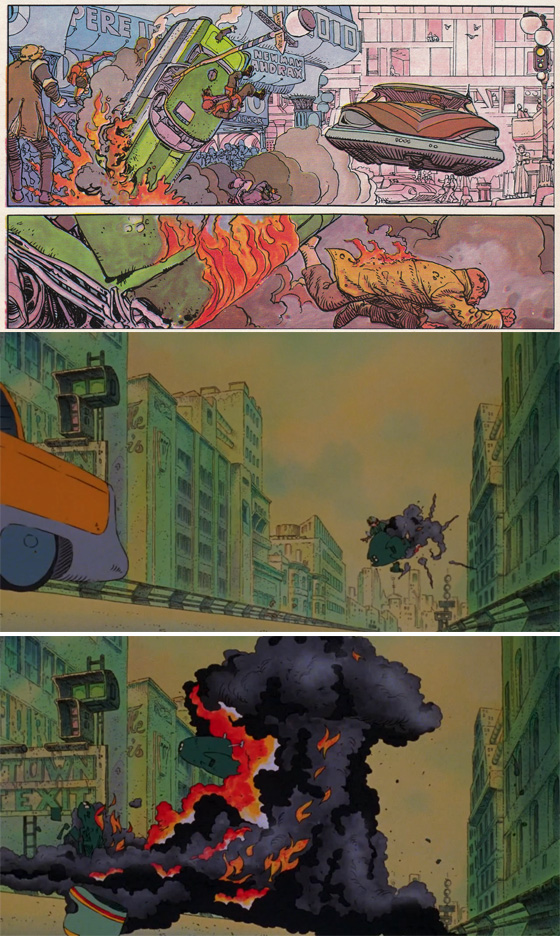

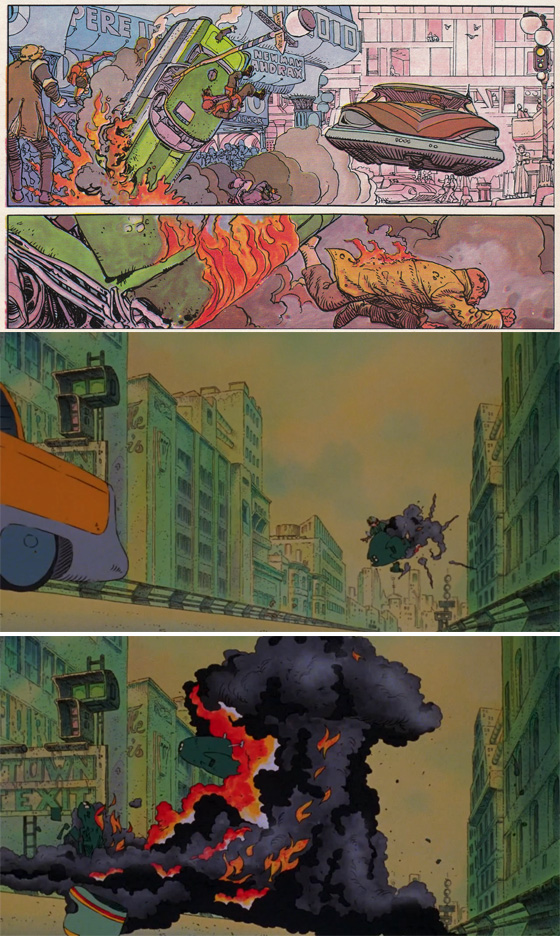

Two sci-fi noirs depict a car chase gone wrong. Top: "The Long Tomorrow" by Dan O'Bannon and Moebius. Bottom: the film's "Harry Canyon."

Dan Goldberg and Len Blum’s “Harry Canyon” is the first full-bodied story in the film, and a fan favorite: the tale of a cynical taxi driver who gets mixed up with a duplicitous dame and some stolen loot (actually the glowing green orb). Storyboards and design are credited to Juan Gimenez, the illustrator of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Metabarons series, though the design of the futuristic New York – sprawling, decaying, and overwhelmed with crass advertisements – owes something to the style of Moebius. His collaboration with Dan O’Bannon, “The Long Tomorrow” (part 1 of which appeared in the July 1977 Heavy Metal), was a hard-boiled detective noir that seems to be the chief inspiration for “Harry Canyon.” Both stories, in turn, borrow liberally from Robert Aldrich’s classic Atomic Age noir Kiss Me Deadly (1955), in which Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer chased a mysterious and deadly box. Part of the reason “Harry Canyon” works so well is that the tough-guy dialogue is obviously parodic; when I saw this film in a packed theater in 1996, one of Harry’s single-entendres during a semi-graphic sex scene earned a big laugh from the crowd. Here you’ll also begin to note the presence of various SCTV performers in the voice cast: John Candy, Eugene Levy, Joe Flaherty, and Harold Ramis all contribute to Heavy Metal. (Harry is voiced by Richard Romanus, the veteran character actor who appeared in Scorsese’s Mean Streets and voiced Weehawk in Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards.)

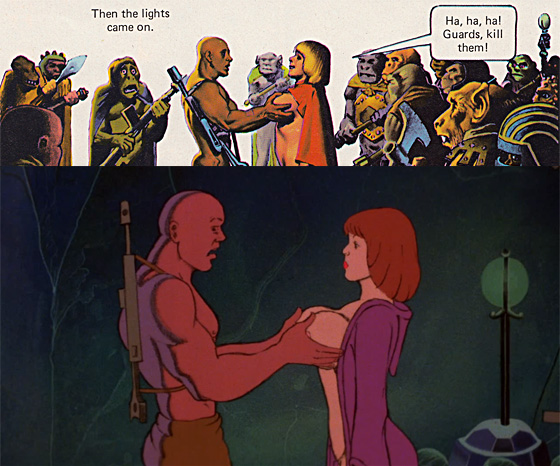

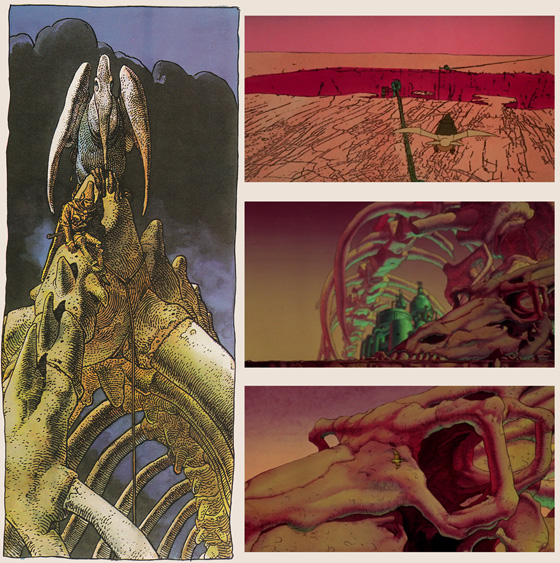

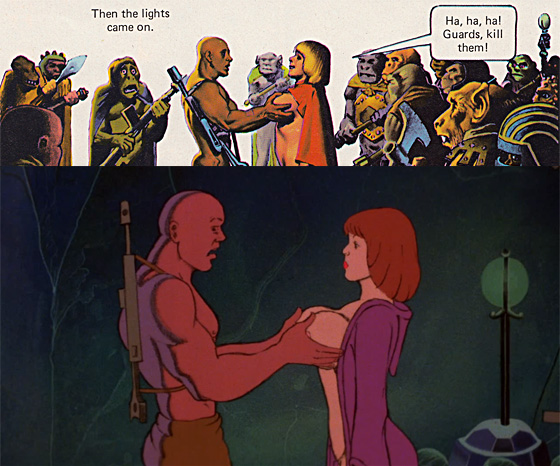

"Den": Richard Corben's lusty comic (top) is adapted for the film (bottom).

Richard Corben’s Den was serialized in Heavy Metal from 1977-78; as much a love-letter to human anatomy as it is the pulp works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, H.P. Lovecraft, and Robert E. Howard, the science fiction/sword & sorcery hybrid tells the story of a scrawny nerd teleported into another dimension, where he becomes the fully-nude, well-endowed warrior Den, and is soon trapped between sorcerers battling for possession of the crystal called the Loc-Nar. Corben’s follow-up, “New Tales of the Arabian Nights,” was originally slated for the film, but work was scrapped to deliver the more straightforward saga of “Den” instead (the love scene between Den and the Queen is actually animated from preliminary sketches for the “Arabian Nights” adaptation). Frankly, I wish they hadn’t changed their minds, but that’s because the first installment of “Arabian Nights,” depicting the tale of Scheherazade, is one of my favorite works of fantasy illustration. Admittedly, Den provides an easier template for a short segment of an anthology film, and delivers enough animated skin to keep the audience awake. It’s not taken the least bit seriously, and the casting of John Candy as the brawny Den is suitably whiplash-inducing. If you’re going to accuse Heavy Metal of being juvenile and stupid T&A, you’re going to point at “Den.” If you’re going to defend the film as silly escapist fun, you’ll point at “Den” too.

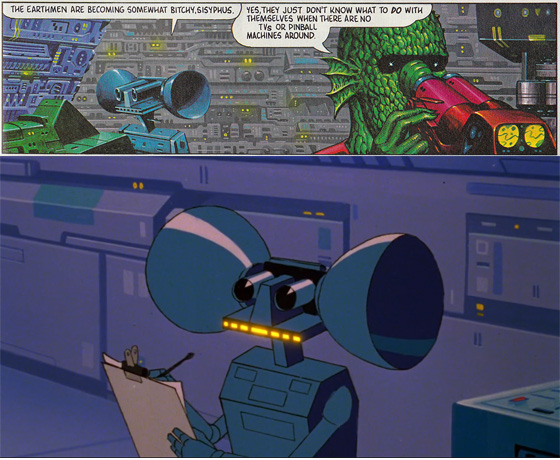

"Captain Sternn": Bernie Wrightson's original (top) and the same moment in the film version (bottom).

Master horror and fantasy illustrator Bernie Wrightson created the uncharacteristically comic “Captain Sternn,” which ran in Heavy Metal and in a 5-part comic book. The animated adaptation, at least from a design standpoint, might be the most impressive segment of Heavy Metal since it follows Wrightson’s panels so devotedly. (In the comparison above, note that even the two googly-eyed aliens in the background are carried over.) Eugene Levy effectively disguises his nasally voice to portray a booming Sternn, and Joe Flaherty plays his nervous lawyer. Unfortunately, it all devolves into a chase scene set to Cheap Trick’s “Reach Out” – not one of their better songs, though the lyrics to “reach out and take it” and “you’ll go the distance/you never thought that you could” amusingly remind one of Dirk Diggler’s inspirational power rock in Boogie Nights.

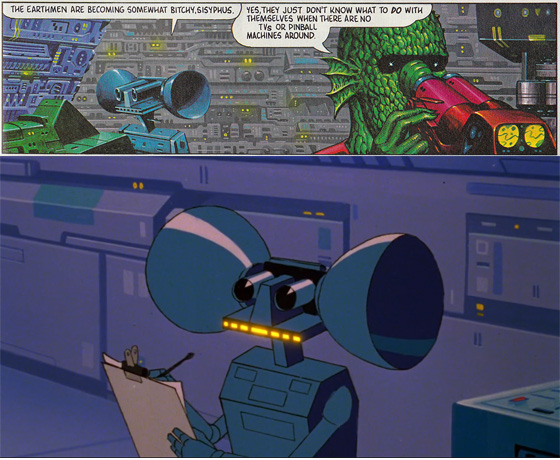

"So Beautiful & So Dangerous": the robot navigator in Angus McKie's original (above) and in the film (bottom).

Luckily, what follows is one of the film’s grooviest songs, Don Felder’s “Heavy Metal (Takin’ a Ride)”, playing over some spectacular rotoscoped animation of a B-17 (model) engaging in a dogfight before a night sky that looks like deep space. Most of the crew is massacred in the fight, and subsequently return to life as zombies to battle the trapped pilot, in this spooky, claustrophobic tale from future Return of the Living Dead (1985) writer/director O’Bannon. Comic book artist Mike Ploog, who also worked on Wizards, helped design the slime-dripping zombies. Next up is another abrupt change of mood: “So Beautiful & So Dangerous” sees an ocular UFO visiting Earth and accidentally abducting a Jewish secretary (Alice Playten). The ship is piloted by two drug-addled aliens (Ramis and Levy) and an efficient robot (Candy) who is equipped to sexually satisfy their captive; marriage follows. This stoner sex comedy is tonally at odds with Angus McKie’s original, which was a cosmic and philosophical saga (a large selection of Earthlings are taken on an interstellar voyage) with more intelligent touches of satire. As an adaptation, it might be a disappointment, but the animation’s design (abetted by Neal Adams, a famed artist for both Marvel and D.C.) and the trippy visuals nonetheless make for an iconic sequence for the film. There’s a contact high; you can almost smell the pot smoke.

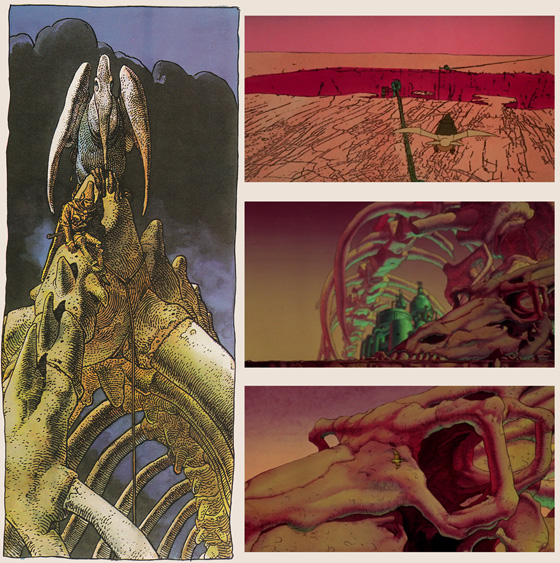

"Taarna" (right) contains visual homages to Moebius' "Arzach" stories (left). Click to enlarge.

The final segment is the longest: “Taarna,” an original story written by the “Harry Canyon” team of Goldberg & Blum. The green orb causes a volcano to erupt, and its spillage transforms the inhabitants of a country into raging barbarians. A secret religious society summons the reincarnation of an ancient female warrior, the white-haired, leather-clad, pterodactyl-riding Taarna, to conquer the enemy. Though Ploog and fellow comic book artist Howard Chaykin are credited among the designers, there are visual quotes to the wordless “Arzach” stories of Moebius (see the above comparison), which appeared in America starting with Heavy Metal #1. This segment and O’Bannon’s “B-17” are the only straight-faced sequences in the film, though if O’Bannon’s was inspired by old E.C. horror comics, “Taarna” takes its queue from Sergio Leone Westerns. In one scene, the heroine strides through the swinging doors of a saloon (where an alien version of Devo is playing “Through Being Cool”) and takes out a couple of baddies with her sword, spilling oodles of green blood. After finally defeating the barbarian leader in a bloody duel, Taarna’s spirit is transmigrated into the body of the young girl who has been forced to listen to stories for a solid ninety minutes. Our evil-orb narrator is destroyed by his own storytelling; he should have kept his mouth shut.

"Taarna": an animated Devo performs "Through Being Cool."

The deadline was fast approaching, and an exploding farmhouse couldn’t be animated, so live-action footage of a model exploding is shown in slow-motion instead. Oh well; at least the film was completed, and there would be nothing else like it in theaters. The international army of animators produced a bona fide cult classic, a film that every science fiction and fantasy aficionado would have to watch as a rite of passage in the decades to come, and judge accordingly. A sequel arrived far too late (Kevin Eastman’s disappointing Heavy Metal 2000), and in the past few years, chatter has begun of a remake: originally to be overseen by David Fincher, though the latest talk has put it in Robert Rodriguez’s ever-growing stable of projects. (Can we give it back to Fincher?) I’d only argue that any remake should take the same approach as the original: divide up the workload and let the animators run wild with their uncensored imaginations. Once, in 1981, it worked.

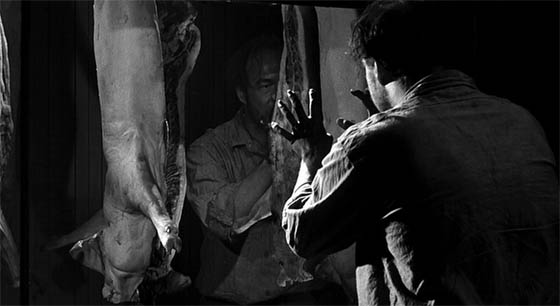

From the late 50’s to the early 60’s, William Castle was on a roll, cranking out one B-picture after another, each generally tempering some classy and competent direction with shameless gimmickry. By early ’64, he was pulling back on the gimmicks, but that doesn’t mean that Strait-Jacket isn’t shameless. The film came in the wake of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), an unlikely horror film that resuscitated the careers of two Hollywood stars of the 30’s and 40’s, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Davis used that film’s success to launch a twilight career in the horror/suspense genre, with Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), The Nanny (1965) and The Anniversary (1968) for Hammer Films, and, later, Burnt Offerings (1976) and The Watcher in the Woods (1980). Crawford also relished being in the spotlight again, whatever the circumstances, and when Castle, a Baby Jane fan, arrived on bended knee with a script by Psycho author Robert Bloch, she accepted – so long as she ruled like a queen on the set. The result was Strait-Jacket, filmed in 1963, the year that saw the release of two William Castle films which were not horror. Strait-Jacket, a psychological thriller with plenty of shocks, would be a return to form for the director/producer/showman.

From the late 50’s to the early 60’s, William Castle was on a roll, cranking out one B-picture after another, each generally tempering some classy and competent direction with shameless gimmickry. By early ’64, he was pulling back on the gimmicks, but that doesn’t mean that Strait-Jacket isn’t shameless. The film came in the wake of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), an unlikely horror film that resuscitated the careers of two Hollywood stars of the 30’s and 40’s, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Davis used that film’s success to launch a twilight career in the horror/suspense genre, with Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), The Nanny (1965) and The Anniversary (1968) for Hammer Films, and, later, Burnt Offerings (1976) and The Watcher in the Woods (1980). Crawford also relished being in the spotlight again, whatever the circumstances, and when Castle, a Baby Jane fan, arrived on bended knee with a script by Psycho author Robert Bloch, she accepted – so long as she ruled like a queen on the set. The result was Strait-Jacket, filmed in 1963, the year that saw the release of two William Castle films which were not horror. Strait-Jacket, a psychological thriller with plenty of shocks, would be a return to form for the director/producer/showman.

It’s all a matter of tone. The Bed Sitting Room (1969) could be the bleakest nuclear apocalypse movie ever made. Its themes, characters, and incidents could be unbearably disturbing; and in many ways they still are. But the ideas are pressed through a filter, which reduces our story to a broad satire that, at times, resembles a dry-as-hell BBC sketch comedy series, and at other times a Looney Tunes cartoon. The Bed Sitting Room is nonetheless haunting, because although it’s a comedy, we know what’s really at stake. Which is everything: our society, our children, our world – us. What I am saying is that you will probably not burst into tears when the end credits roll. In fact, the minds behind this film have actively worked to prevent that. The poster should have boasted that ambiguous guarantee: “You’ll laugh until your sides hurt, which means there is a very good chance that you will not succumb to existential despair. Look! Look at the funny parrot and watch Dudley Moore transform into a cute little dog! We will all die in the end.”

It’s all a matter of tone. The Bed Sitting Room (1969) could be the bleakest nuclear apocalypse movie ever made. Its themes, characters, and incidents could be unbearably disturbing; and in many ways they still are. But the ideas are pressed through a filter, which reduces our story to a broad satire that, at times, resembles a dry-as-hell BBC sketch comedy series, and at other times a Looney Tunes cartoon. The Bed Sitting Room is nonetheless haunting, because although it’s a comedy, we know what’s really at stake. Which is everything: our society, our children, our world – us. What I am saying is that you will probably not burst into tears when the end credits roll. In fact, the minds behind this film have actively worked to prevent that. The poster should have boasted that ambiguous guarantee: “You’ll laugh until your sides hurt, which means there is a very good chance that you will not succumb to existential despair. Look! Look at the funny parrot and watch Dudley Moore transform into a cute little dog! We will all die in the end.”

Heavy Metal magazine debuted in the U.S. in the spring of 1977 with the image of a pointy-breasted robot bashing to pieces another robot with a wrench. The publishers of the National Lampoon had compiled this “adult illustrated fantasy magazine” primarily from the contents of the French Metal Hurlant (“Screaming Metal”), which had already been going for several years and had become a phenomenon in Europe. That magazine was published by Les Humanoides Associes, an organization fronted by artists Philippe Druillet and Jean Giraud (aka “Moebius”), writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, and Bernard Farkas. The comics in Metal Hurlant were typically stream-of-consciousness, erotic, violent, grotesque, and gorgeous. Heavy Metal editors Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant translated and serialized the best of the Hurlant stories, adding into the mix prose from noted science fiction and fantasy authors (Terry Brooks in the first issue, and later James Tiptree, Jr., Theodore Sturgeon, and even Steven Spielberg, excerpting his novelization of Close Encounters of the Third Kind), as well as comics from well-known American artists like Richard Corben and the recently-deceased Vaughn Bodé. Heavy Metal arrived at the right time. Star Wars was released that spring, and science fiction was the rage, but this magazine went to places George Lucas could never go: it was druggy, taboo-flaunting, funny, and oversexed. It was a hit.

Heavy Metal magazine debuted in the U.S. in the spring of 1977 with the image of a pointy-breasted robot bashing to pieces another robot with a wrench. The publishers of the National Lampoon had compiled this “adult illustrated fantasy magazine” primarily from the contents of the French Metal Hurlant (“Screaming Metal”), which had already been going for several years and had become a phenomenon in Europe. That magazine was published by Les Humanoides Associes, an organization fronted by artists Philippe Druillet and Jean Giraud (aka “Moebius”), writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, and Bernard Farkas. The comics in Metal Hurlant were typically stream-of-consciousness, erotic, violent, grotesque, and gorgeous. Heavy Metal editors Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant translated and serialized the best of the Hurlant stories, adding into the mix prose from noted science fiction and fantasy authors (Terry Brooks in the first issue, and later James Tiptree, Jr., Theodore Sturgeon, and even Steven Spielberg, excerpting his novelization of Close Encounters of the Third Kind), as well as comics from well-known American artists like Richard Corben and the recently-deceased Vaughn Bodé. Heavy Metal arrived at the right time. Star Wars was released that spring, and science fiction was the rage, but this magazine went to places George Lucas could never go: it was druggy, taboo-flaunting, funny, and oversexed. It was a hit.