A common reference point for teenage boys everywhere, The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977) launched the cinematic careers of “ZAZ” (David Zucker, Jim Abrahams, and Jerry Zucker) and helped establish young John Landis as a comedy director of note. In three years ZAZ would make Airplane! (1980), a benchmark of 80’s comedy that would lead, in turn, to the television series Police Squad! (1982), Top Secret! (1984), and The Naked Gun (1988). Not bad for three boys from UW-Madison. Landis, meanwhile, would film Animal House in 1978 and graduate immediately to the big leagues. The Kentucky Fried Movie looks every cent of its very low budget, but over the decades it’s held its own as a cult classic while its creators went on to bigger and better things.

A common reference point for teenage boys everywhere, The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977) launched the cinematic careers of “ZAZ” (David Zucker, Jim Abrahams, and Jerry Zucker) and helped establish young John Landis as a comedy director of note. In three years ZAZ would make Airplane! (1980), a benchmark of 80’s comedy that would lead, in turn, to the television series Police Squad! (1982), Top Secret! (1984), and The Naked Gun (1988). Not bad for three boys from UW-Madison. Landis, meanwhile, would film Animal House in 1978 and graduate immediately to the big leagues. The Kentucky Fried Movie looks every cent of its very low budget, but over the decades it’s held its own as a cult classic while its creators went on to bigger and better things.

"If you're a Gemini like me, you can expect the unexpected."

The Kentucky Fried Theater was a comedy group ZAZ had formed in 1971 while attending the UW; Dick Chudnow completed the cast. Rich Markey, an early KFT fan, indicates the creation of the sketch group was inevitable given the students’ penchant for street theater: “For example…Abrahams would wrap his foot in bandages to resemble a cast, and hobble into a study room with an armful of books. When Abrahams arrived, Chudnow got up to leave, and as he passed Abrahams, he kicked the cane out from under him and down he went — splat! Books everywhere. Chudnow would grab the cane and whack Abrahams with it a few times and then run… Once, a couple of outraged students chased after Chudnow all the way out into the street.” Their knack for comic inspiration led to the formation of the KFT, a multi-media sketch show which performed in various venues across Madison (including the old Union South, which has just been rebuilt) before transporting itself to Los Angeles in 1972. There, they inadvertently helped inspire the creation of Saturday Night Live when Lorne Michaels witnessed a show; they also performed their “Fried Egg” routine on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. Dick Chudnow left the group, stating that all the attention was making him “uncomfortable,” and sold the rights to his KFT material to ZAZ. But Abrahams and the Zuckers had stars in their eyes; if they could get a feature film made, their material would reach a much wider audience.

Catholic School Girls in Trouble

John Landis had been actively working in Hollywood for several years, beginning his career in the mail room at 20th Century Fox and quickly climbing up through the ranks. With some friends he had made the B-movie send-up Schlock (1973), which featured future Oscar-winner Rick Baker in a gorilla suit, and gained some favorable notices but didn’t exactly light up the box office. In an interview in the Fall 1973 Cinefantastique, Landis confidently talked up his next projects: “One is called An American Werewolf in Paris, which is very funny and very frightening. Teenage Vampire is another one. I’ve always wanted to make Island of Dr. Moreau since I was four, and I intend to; also A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.” Though he’d eventually make that first project (with a change in locale), Schlock wasn’t the calling card he’d hoped it would be, and he languished as a script doctor and production assistant. It would be another four years before he teamed up with ZAZ, and by this point, they needed each other. The Kentucky Fried Movie would take the best of the sketch team’s live material with some new, more cinema-friendly parodies thrown in. It was good timing: SNL was by now popularizing irreverent, adult-oriented sketch comedy, and a few R-rated sketch films were beginning to appear at the box office, movies like The Groove Tube (1974), Tunnelvision (1976), and American Raspberry (1977). There was room for ZAZ and Landis to offer their own take, and certainly plenty of opportunity to improve on what had been a pretty dismal subgenre thus far.

"High Adventure": an interviewer (Joe Medalis), his subject (Barry Dennen), and their boom mic.

I might quibble about The Kentucky Fried Movie. I might suggest that some of the jokes are too stupid, or too immature. Or that the film could be given a stronger internal logic (is the viewer supposedly watching this lineup on late-night television, or in a movie theater?). Or that some of the segments might be rearranged for more impact – for example, one sketch involving a man being physically slapped about and abused (“Feel-Around”) shouldn’t be followed immediately by a commercial parody in which the same thing happens (“Nytex P.M.”). Except that these really are quibbles, and, unlike its forebears (with the exception of the Monty Python films, and Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask, which had the benefit of Woody Allen’s wit), the movie hits more often than it misses. It’s funny. That’s all that matters. The ZAZ style is to tell very dumb jokes, but relentlessly; to hammer away at them until you surrender. Be honest with yourself: “Don’t call me Shirley” is not particularly hilarious. That is, unless Peter Graves is delivering the line, and without any trace of a smile. The Kentucky Fried Movie injures the dignity of more respectable actors: the chaotic and overstuffed disaster movie trailer “That’s Armageddon” features former 007 George Lazenby trapped in an infinitely repeating page of circular dialogue, from which there is no escape (“What are you saying?”), and Donald Sutherland plays the “clumsy waiter” (he falls into a cake – that’s it). In “Courtroom,” Tony Dow reprises his role as Leave it to Beaver‘s Wally, looking exactly the same, while he sincerely delivers his dopey lines to a perfectly-cast Jerry Zucker as the Beav. When the witness breaks into tears, Beaver stammers, “You wouldn’t cry if you was just gettin’ yelled at, would ya, Wally?” “Heck no, Beav. Girls are different. I mean, if a guy cried, everybody would think he was a creep or somethin’.”

"Courtroom" - Jim Abrahams narrates a tense trial.

Landis indulges the film’s R-rating with “Catholic School Girls in Trouble,” a parody of every sexploitation and porno of the 70’s. The actresses are given wink-wink names such as Linda Chambers and Nancy Reems. The famously-endowed Uschi Digard (of Russ Meyer’s Supervixens) plays “The Woman in the Shower,” and if you have seen this film, I’m betting that you remember her brief role. Landis also throws in a dwarf in a clown outfit whipping some girls chained up in a dungeon, just to cover the bases. This is a film made for in-jokes, and naturally Landis’s fictional “See You Next Wednesday” (taken from a line in 2001: A Space Odyssey) appears on a marquee; you’ll see more of the film in An American Werewolf in London (1981). A poster for Schlock is hanging in the lobby. Landis, a movie junkie, really seems more at home with the film parodies, such as the whimsical “Cleopatra Schwartz,” in which a scantily-clad Pam Grier lookalike (Marilyn Joi), outfitted with heavy artillery, weds an Orthodox Jew (Saul Kahan). But the film’s singular triumph is “A Fistful of Yen,” the sustained Enter the Dragon parody which fills out about half of The Kentucky Fried Movie‘s running time.

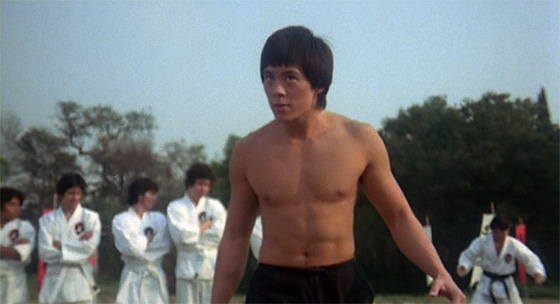

"A Fistful of Yen" - Evan Kim as Loo

Evan Kim plays Loo, applying (and only slightly exaggerating) Bruce Lee’s speech impediment, as well as a fair imitation of his martial arts skills. Ironically, he’s probably the best of the Lee imitators that followed in the wake of the actor’s death in 1973; the preponderance of rip-offs was still glutting theaters by the time this film was released. But Evan Kim doesn’t just look the part; seldom noted is just how perfect his comic timing is – and how good he looks in Dorothy Gale pigtails. Abrahams and the Zuckers write a script so close to Enter the Dragon that it often directly borrows that film’s dialogue, just to pick it apart and skewer it (“these people are drunk, and don’t know where they are”). As the one-handed Dr. Klahn, Master Bong Soo Han looks almost exactly like Kien Shih’s “Han” of the original film. It’s difficult to parody that character, considering how ridiculous it was in the first place (most of his various instruments of death, and the skeleton hand in a jar, all originate in Enter the Dragon). But simple touches like repeating the villain’s unintentional rhyme of “magnitude” and “gratitude,” or showing what his answering machine might be like, are inspired. For his part, Landis apes the style of Hong Kong martial arts films, with zooms, slow-motion, and extreme close-ups of intense-looking stares; the perfect compliment to his writers’ non sequitur gags, including a kung fu match-up which devolves, somehow, into a Love Connection parody.

"A Fistful of Yen": Careful, the room might be bugged.

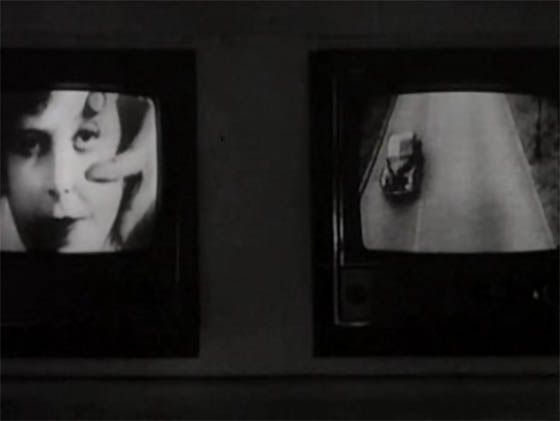

Whatever my ineffectual quibbles about the arrangement of the sketches, “A Fistful of Yen” is placed perfectly in the center of the film, so that you get a break from the local news, TV commercial, and movie trailer spoofs, which would be an overload if filling out the full 90 minutes. It gives a chance to relax into a narrative, if an absurd one; and it provides such rewards that Airplane!, which applies the same treatment to the Airport films, is a natural evolution. Finally, The Kentucky Fried Movie serves up a sketch from their live show: some sexual activity in the living room is so heated that it begins to distract the anchorman on the television. Did I mention that this film is a favorite of teenage boys across the United States? Some more gratuitous T&A is served, and a novel but simple gag that leads to a very literal climax for the film. I’m sure the pun is intentional. If you haven’t learned by now, the Zuckers and Abrahams weren’t above that sort of thing; and we should all be glad for it.

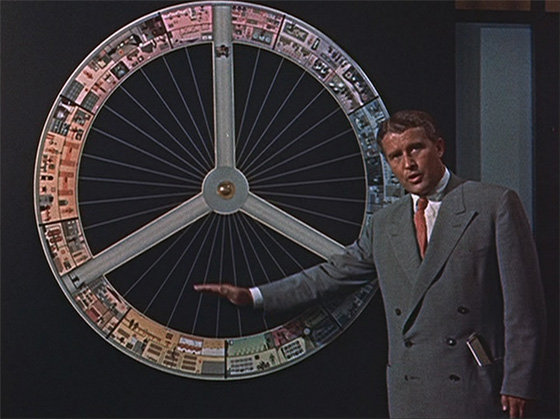

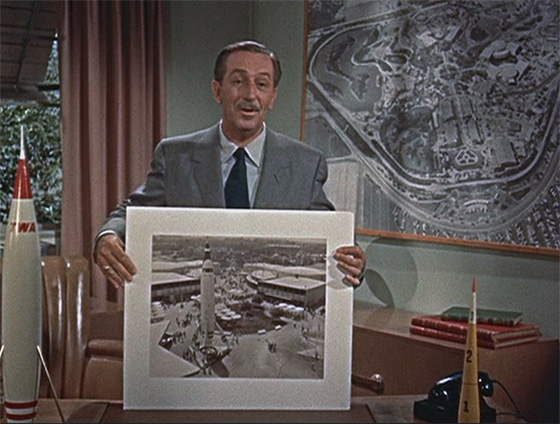

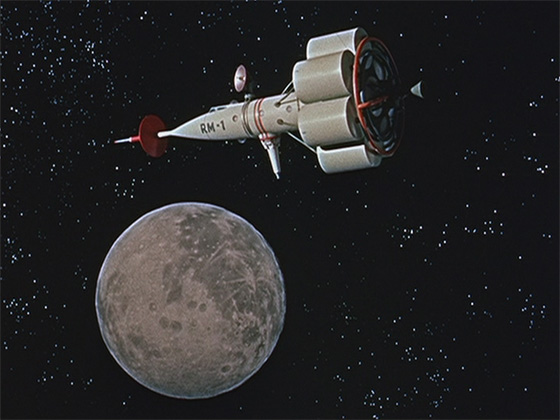

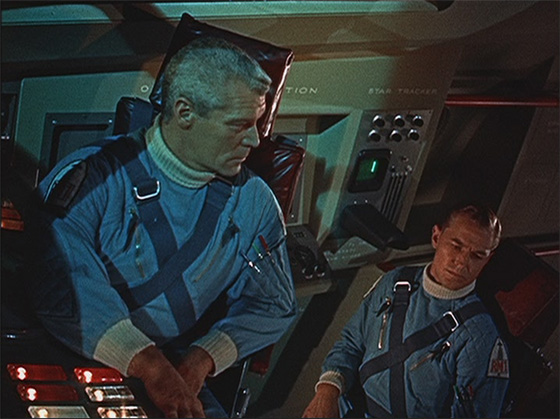

Walt Disney opened his Disneyland theme park on July 18, 1955, in Anaheim, California – just thirty-two miles from Hollywood. Disney had conquered cinema already, and now he had his sights set on a multi-media entertainment empire. In October of that year he premiered his television series on the ABC network, at first called Disneyland, in honor (and cross-promotion) of the park; it would later become Walt Disney Presents and, eventually, The Wonderful World of Disney. Through its various permutations, the anthology program would spotlight Disney animated shorts and films, made-for-TV movies, nature documentaries, behind-the-scenes specials on the Disney theme parks, Davy Crockett episodes and more. In the show’s earliest days, each week would present a theme program inspired by a particular section of Disneyland: Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland, and, most intriguingly, Tomorrowland, which gave Disney the license to produce an hour of science-fact entertainment, and educate viewers on the solar system and the future of space exploration. These big-budget productions brought in Wernher von Braun as both a consultant and an on-screen personality.

Walt Disney opened his Disneyland theme park on July 18, 1955, in Anaheim, California – just thirty-two miles from Hollywood. Disney had conquered cinema already, and now he had his sights set on a multi-media entertainment empire. In October of that year he premiered his television series on the ABC network, at first called Disneyland, in honor (and cross-promotion) of the park; it would later become Walt Disney Presents and, eventually, The Wonderful World of Disney. Through its various permutations, the anthology program would spotlight Disney animated shorts and films, made-for-TV movies, nature documentaries, behind-the-scenes specials on the Disney theme parks, Davy Crockett episodes and more. In the show’s earliest days, each week would present a theme program inspired by a particular section of Disneyland: Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland, and, most intriguingly, Tomorrowland, which gave Disney the license to produce an hour of science-fact entertainment, and educate viewers on the solar system and the future of space exploration. These big-budget productions brought in Wernher von Braun as both a consultant and an on-screen personality.

You may have noticed, if you check in here at all, that beginning in the summer I began to ramp up the amount of material posted on this still-developing website. It’s a challenge for one person to provide so much content, particularly when said fellow has a daily (paying) job to contend with, and my fear is that overambition takes a toll on the quality of the pieces posted here.

You may have noticed, if you check in here at all, that beginning in the summer I began to ramp up the amount of material posted on this still-developing website. It’s a challenge for one person to provide so much content, particularly when said fellow has a daily (paying) job to contend with, and my fear is that overambition takes a toll on the quality of the pieces posted here.