- Welcome to the theater. Mind the leaking roof.

-

Recent Posts

Tags

30's 40's 50's 60's 70's 80's Action AIP A Month at the Grindhouse Animation cheesecake Christopher Lee Comedy Dracula Drama fairy tale Fantasy Frankenstein Hammer Haunted House horror Japan Jean Rollin lovable animals Madness Patrick McGoohan Peter Cushing Psychedelic Rock Musical Roger Corman Russian Satanism Science Fiction sexploitation slapstick Slasher Stop Motion Surreal Sword and Sorcery The Devil The Prisoner Vampire Witch witches Zombie-

Blogroll

- AV Club

- Backlots

- Christina Wehner

- Cinematic Catharsis

- Classic Film & TV Cafe

- Classic Horror Film Board

- Criterion Forum

- Dave Kehr

- DVD Beaver

- DVD Drive-In

- DVD Maniacs

- Fascination: The Jean Rollin Experience

- Goregirl's Dungeon

- Jeff Kuykendall

- Last Drive-In

- Mobius Home Video Forum

- Paracinema Magazine

- Psychotronica Redux

- Satellite News (MST3K)

- Shout! Factory

- Silver Screenings

- Tim Lucas / Video Watchdog

- Trailers from Hell

-

-

Trailer: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978)

Posted in Coming Attractions

Tagged 70's, Beatles, Bee Gees, Disco, Psychedelic, Rock Musical, slapstick

Comments Off on Trailer: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978)

On the Comet (1970)

Karel Zeman (1910-1989) was a Czechoslovakian animator and filmmaker whose shorts and feature length films are like multi-media playgrounds in which actors move amongst baroque painted backdrops, interact with stop-motion animated creatures matted against deliberately flat, Victorian-style paintings and cut-outs, and seem to exist in several different planes of reality at once. Imagine an old, musty storybook springing to life and crawling off your lap. I encountered the world of Zeman as a child by stumbling right into the deep end: Na Komete (On the Comet, or Off on the Comet), his 1970 film in which Zeman continues to hone the handmade techniques developed in his earlier films like The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), Baron Prásil (aka The Fabulous Baron Munchausen, 1962), and The Jester’s Tale (1964). On the Comet sat on the shelf at the video store in the Science Fiction section, with an undistinguished cover, and I rented it only when I’d already rented everything else in that section which wasn’t rated R. What I got melted my little mind; I was alternately baffled, excited, bored, and baffled again.

Karel Zeman (1910-1989) was a Czechoslovakian animator and filmmaker whose shorts and feature length films are like multi-media playgrounds in which actors move amongst baroque painted backdrops, interact with stop-motion animated creatures matted against deliberately flat, Victorian-style paintings and cut-outs, and seem to exist in several different planes of reality at once. Imagine an old, musty storybook springing to life and crawling off your lap. I encountered the world of Zeman as a child by stumbling right into the deep end: Na Komete (On the Comet, or Off on the Comet), his 1970 film in which Zeman continues to hone the handmade techniques developed in his earlier films like The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), Baron Prásil (aka The Fabulous Baron Munchausen, 1962), and The Jester’s Tale (1964). On the Comet sat on the shelf at the video store in the Science Fiction section, with an undistinguished cover, and I rented it only when I’d already rented everything else in that section which wasn’t rated R. What I got melted my little mind; I was alternately baffled, excited, bored, and baffled again.

What I was actually watching was a badly dubbed and cropped presentation of a Czech fantasy film based on a two-part Jules Verne novel (1877’s Hector Servadac, which consists of To the Sun? and Off on a Comet!), being among the most obscure of his Les Voyages Extraordinaires science-fiction books. Though I quickly moved on as soon as the film ended, I never quite forgot that there was this very, very strange film – something with “comet” in the title – and as the years passed I began to wonder if I’d only dreamed it. (There are still several films I watched as a child which I’m trying to locate. If anyone knows of a TV-movie about a sorcerer’s apprentice which uses the America song “You Can Do Magic,” please let me know. Or maybe that one really was a dream.) So to prepare for tonight’s midnight movie, I tackled my childhood memory head-on. First I ordered a copy of the VHS tape – same tacky cover – off Amazon Marketplace, along with a 1960 edition of the Verne novel upon which it’s based. I endured all 460 pages of Hector Servadac, and was reminded of why I’ve always preferred H.G. Wells. When complaining to my father-in-law of the book’s rancid, and nonstop, anti-semitism, along with insufferable lectures on 19th-century astrophysics (a professor gives a speech which lasts for about 50 pages – even after one of Verne’s characters falls asleep!), he suggested that perhaps I didn’t need to read this book; after all, wasn’t it evident by now that the film couldn’t possibly be a faithful adaptation? Yes, true, but as a former English major, I have a dogged commitment to finishing books I start; and anyway, I wanted all the help I could get to shed light on this particularly blurry childhood memory. I wanted the context and background for On the Comet. In retrospect, I should have been watching other Karel Zeman films instead, but live and learn.

What I was actually watching was a badly dubbed and cropped presentation of a Czech fantasy film based on a two-part Jules Verne novel (1877’s Hector Servadac, which consists of To the Sun? and Off on a Comet!), being among the most obscure of his Les Voyages Extraordinaires science-fiction books. Though I quickly moved on as soon as the film ended, I never quite forgot that there was this very, very strange film – something with “comet” in the title – and as the years passed I began to wonder if I’d only dreamed it. (There are still several films I watched as a child which I’m trying to locate. If anyone knows of a TV-movie about a sorcerer’s apprentice which uses the America song “You Can Do Magic,” please let me know. Or maybe that one really was a dream.) So to prepare for tonight’s midnight movie, I tackled my childhood memory head-on. First I ordered a copy of the VHS tape – same tacky cover – off Amazon Marketplace, along with a 1960 edition of the Verne novel upon which it’s based. I endured all 460 pages of Hector Servadac, and was reminded of why I’ve always preferred H.G. Wells. When complaining to my father-in-law of the book’s rancid, and nonstop, anti-semitism, along with insufferable lectures on 19th-century astrophysics (a professor gives a speech which lasts for about 50 pages – even after one of Verne’s characters falls asleep!), he suggested that perhaps I didn’t need to read this book; after all, wasn’t it evident by now that the film couldn’t possibly be a faithful adaptation? Yes, true, but as a former English major, I have a dogged commitment to finishing books I start; and anyway, I wanted all the help I could get to shed light on this particularly blurry childhood memory. I wanted the context and background for On the Comet. In retrospect, I should have been watching other Karel Zeman films instead, but live and learn.

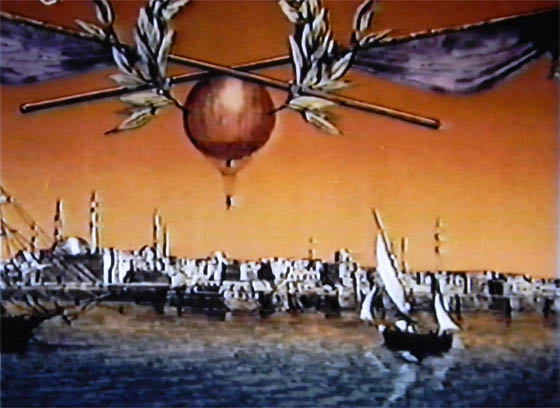

So, no – I can say now – On the Comet doesn’t have much to do with Jules Verne. Like most Verne adaptations, Zeman takes the premise and fills in plenty of colorful and fantastic details, along with some political satire. What grabbed me straight away was the look of the film. Although it begins with a color sequence – an old man introduces the story, which is essentially a flashback to his youth – the majority of the film is tinted black-and-white footage, most of it glowing a golden color to represent the desert heat of Algeria, but shifting, at times, to blue, red, or other shades to complement the scene. The opening credits use Victorian postcards, establishing Zeman’s principal motif. The first scene in the film is a moving diorama: a soldier is suspended in a balloon over a two-dimensional painting of a North African city; the live-action fellow is matted into the image which includes animated seagulls flying past him. It looks like one of the opening-credit postcards. Then he accidentally drops his lit cigar, setting fire to the city below; an Algerian child weeps while his city burns. Welcome to On the Comet. This is not an ordinary fantasy film.

So, no – I can say now – On the Comet doesn’t have much to do with Jules Verne. Like most Verne adaptations, Zeman takes the premise and fills in plenty of colorful and fantastic details, along with some political satire. What grabbed me straight away was the look of the film. Although it begins with a color sequence – an old man introduces the story, which is essentially a flashback to his youth – the majority of the film is tinted black-and-white footage, most of it glowing a golden color to represent the desert heat of Algeria, but shifting, at times, to blue, red, or other shades to complement the scene. The opening credits use Victorian postcards, establishing Zeman’s principal motif. The first scene in the film is a moving diorama: a soldier is suspended in a balloon over a two-dimensional painting of a North African city; the live-action fellow is matted into the image which includes animated seagulls flying past him. It looks like one of the opening-credit postcards. Then he accidentally drops his lit cigar, setting fire to the city below; an Algerian child weeps while his city burns. Welcome to On the Comet. This is not an ordinary fantasy film.

The hero is Lieutenant Servadac (Emil Horvath), and although his faithful, comic-relief companion Ben Zouf (Karel Effa) is present, Zeman changes Verne’s novel into a love story, introducing a beautiful young woman (Magda Vásáryová) for whom Servadac develops a fascination after he sees her image on a postcard in an Algerian market. While working a land survey with Ben, he stumbles off the edge of a cliff, landing in the sea. In a fabulous, blue-tinted sequence, we see bubbles float about Servadac’s head, glowing, undulating jellyfish, and the woman herself, like a mermaid of the deeps, holding a rose that an animated cut-out of a fish snatches out of her hand and carries away. When Servadac comes out of this reverie, he’s lying on a beach with the woman, named Angelika, leaning over him. She explains that she’s just escaped from a ship commanded by a corrupt Sheik, who’s plotting with the Spanish to spark a revolution in French Algiers. But overhead, a giant heavenly body appears in the sky like a rising moon, throwing lightning bolts and glowing green. Servadac and Angelika run from the comet, back into the walls of Algiers, where the French commander sits in a devastated, war-fraught city. His headquarters is the towering mosque, and there’s some comic business involving dust from the hole in the dome constantly falling upon his desk. (Double-feature idea: this, and Pontecorvo’s raw 1966 docudrama The Battle of Algiers. Just throwing that out there.)

The hero is Lieutenant Servadac (Emil Horvath), and although his faithful, comic-relief companion Ben Zouf (Karel Effa) is present, Zeman changes Verne’s novel into a love story, introducing a beautiful young woman (Magda Vásáryová) for whom Servadac develops a fascination after he sees her image on a postcard in an Algerian market. While working a land survey with Ben, he stumbles off the edge of a cliff, landing in the sea. In a fabulous, blue-tinted sequence, we see bubbles float about Servadac’s head, glowing, undulating jellyfish, and the woman herself, like a mermaid of the deeps, holding a rose that an animated cut-out of a fish snatches out of her hand and carries away. When Servadac comes out of this reverie, he’s lying on a beach with the woman, named Angelika, leaning over him. She explains that she’s just escaped from a ship commanded by a corrupt Sheik, who’s plotting with the Spanish to spark a revolution in French Algiers. But overhead, a giant heavenly body appears in the sky like a rising moon, throwing lightning bolts and glowing green. Servadac and Angelika run from the comet, back into the walls of Algiers, where the French commander sits in a devastated, war-fraught city. His headquarters is the towering mosque, and there’s some comic business involving dust from the hole in the dome constantly falling upon his desk. (Double-feature idea: this, and Pontecorvo’s raw 1966 docudrama The Battle of Algiers. Just throwing that out there.)

The comet hits the Earth just when the Sheik’s army sets off a bomb near the French troops and ride out against the city walls. The novel portrays this catastrophic event vaguely: a mist envelops the Earth, there’s a great earthquake, and pretty soon a section of North Africa and the Mediterranean are riding the comet away through the solar system. Zeman illustrates the impact by animating his characters flying through the air (a military band continues to play their instruments while airborne), and buildings splitting into jigsaw pieces and sailing vertically. Then everything falls back into place, including the buildings, which reassemble as the animation is reversed. Servadac immediately determines that they’re riding a comet, as he identifies the Earth disappearing into the sky (in the novel, it takes about 200 pages to draw this conclusion, but this film is only 74 minutes long, so Zeman gets efficient). From the besieged city, strange events are observed. A mutated giant fly is swatted over the commander’s desk. Beyond the walls, dinosaurs join the siege. Servadac rides out and frightens the dinosaurs off by dragging a wagon of clanging pots and pans. This technique so impresses the commander that he orders all the cannons thrown over the walls, and replaced by poles bearing strung-up kitchenware to rattle at invaders.

The comet hits the Earth just when the Sheik’s army sets off a bomb near the French troops and ride out against the city walls. The novel portrays this catastrophic event vaguely: a mist envelops the Earth, there’s a great earthquake, and pretty soon a section of North Africa and the Mediterranean are riding the comet away through the solar system. Zeman illustrates the impact by animating his characters flying through the air (a military band continues to play their instruments while airborne), and buildings splitting into jigsaw pieces and sailing vertically. Then everything falls back into place, including the buildings, which reassemble as the animation is reversed. Servadac immediately determines that they’re riding a comet, as he identifies the Earth disappearing into the sky (in the novel, it takes about 200 pages to draw this conclusion, but this film is only 74 minutes long, so Zeman gets efficient). From the besieged city, strange events are observed. A mutated giant fly is swatted over the commander’s desk. Beyond the walls, dinosaurs join the siege. Servadac rides out and frightens the dinosaurs off by dragging a wagon of clanging pots and pans. This technique so impresses the commander that he orders all the cannons thrown over the walls, and replaced by poles bearing strung-up kitchenware to rattle at invaders.

The dinosaurs are, by turns, traditionally animated, stop-motion animated, and manipulated puppets. Later in the film, Servadac leads a voyage on a steamship across the sea, and discovers a “lost world” crawling with dinosaurs. They even witness evolution first-hand, enacted at an accelerated pace: a fish with legs struts along the ground, and then grows the head of a wild boar, which prompts Ben Zouf’s suggestion that they go hunting. Verne has no dinosaurs in his book (just a volcano), but Zeman seems to enjoy pushing his Victorian-style fantasies into the realm of semi-psychedelic surrealism. Time and again On the Comet resembles the work of Terry Gilliam, who, at the time, was creating similar work in his stream-of-consciousness, Victorian cut-out animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus. (His 1988 film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen also features a besieged city as its dominant setpiece.) The style in which Zeman presents his dinosaurs calls back as far as Willis O’Brien’s work on The Lost World (1925), but even more so the seminal animated film from Winsor McCay, “Gertie the Dinosaur” (1914). And his painted, two-dimensional sets deliberately evoke the work of Georges Méliès in “La voyage dans la lune” (1902) and his many other shorts.

The dinosaurs are, by turns, traditionally animated, stop-motion animated, and manipulated puppets. Later in the film, Servadac leads a voyage on a steamship across the sea, and discovers a “lost world” crawling with dinosaurs. They even witness evolution first-hand, enacted at an accelerated pace: a fish with legs struts along the ground, and then grows the head of a wild boar, which prompts Ben Zouf’s suggestion that they go hunting. Verne has no dinosaurs in his book (just a volcano), but Zeman seems to enjoy pushing his Victorian-style fantasies into the realm of semi-psychedelic surrealism. Time and again On the Comet resembles the work of Terry Gilliam, who, at the time, was creating similar work in his stream-of-consciousness, Victorian cut-out animations for Monty Python’s Flying Circus. (His 1988 film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen also features a besieged city as its dominant setpiece.) The style in which Zeman presents his dinosaurs calls back as far as Willis O’Brien’s work on The Lost World (1925), but even more so the seminal animated film from Winsor McCay, “Gertie the Dinosaur” (1914). And his painted, two-dimensional sets deliberately evoke the work of Georges Méliès in “La voyage dans la lune” (1902) and his many other shorts.

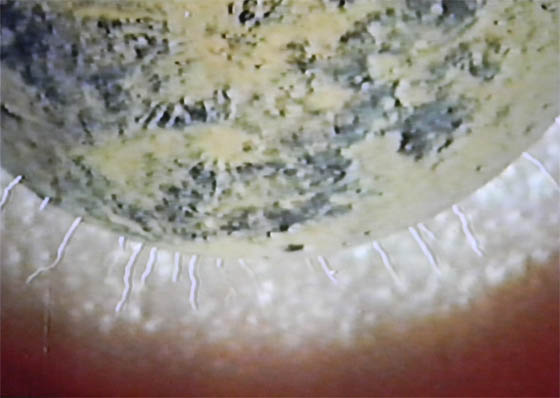

A close encounter with Mars convinces the inhabitants of the comet that doomsday is imminent, and so the battle is cancelled. When Mars passes safely by, the Sheik immediately resumes the assault. This plot, of Zeman’s invention, makes it clear that On the Comet is a satire; unlike Verne’s cast, the French, Algerian, and Spanish characters assembled for the film couldn’t care less that they are accidental explorers of the solar system. Their gaze is seldom fixed toward the sky. Thankfully, the film is not overlong, as the melodramatics of the plot are often tedious. Angelika and Servadac fall in love, and get married (after she fights off some jealous harem girls); the Sheik is always plotting; the French commander reacts with bullheaded stupidity, and so on. What’s most intriguing is a semi-lyrical conclusion which implies that it was all Servadac’s dream inspired by the postcard image of Angelika. This might be the most proper way to conclude a film like On the Comet, which piles on surrealism and absurdity. I can say now that I have seen this as an adult, and it still somehow cannot be captured. Appropriate, I guess, that I didn’t have the TV tuner in my computer to directly capture images from the VHS tape. I had to settle for snapping pictures with a camera of the television, like chasing Bigfoot. I can now replace my old and faded childhood memories, but On the Comet remains stubbornly elusive.

A close encounter with Mars convinces the inhabitants of the comet that doomsday is imminent, and so the battle is cancelled. When Mars passes safely by, the Sheik immediately resumes the assault. This plot, of Zeman’s invention, makes it clear that On the Comet is a satire; unlike Verne’s cast, the French, Algerian, and Spanish characters assembled for the film couldn’t care less that they are accidental explorers of the solar system. Their gaze is seldom fixed toward the sky. Thankfully, the film is not overlong, as the melodramatics of the plot are often tedious. Angelika and Servadac fall in love, and get married (after she fights off some jealous harem girls); the Sheik is always plotting; the French commander reacts with bullheaded stupidity, and so on. What’s most intriguing is a semi-lyrical conclusion which implies that it was all Servadac’s dream inspired by the postcard image of Angelika. This might be the most proper way to conclude a film like On the Comet, which piles on surrealism and absurdity. I can say now that I have seen this as an adult, and it still somehow cannot be captured. Appropriate, I guess, that I didn’t have the TV tuner in my computer to directly capture images from the VHS tape. I had to settle for snapping pictures with a camera of the television, like chasing Bigfoot. I can now replace my old and faded childhood memories, but On the Comet remains stubbornly elusive.

Apparently a DVD, in Czech with English subtitles, will be released on October 3rd. In the meantime, it’s still pretty difficult to see Karel Zeman’s work in this country, but there are lots of clips from his films on YouTube. I doubt I’m done with him, and will check back with more in the future.

Posted in Theater Fantastique

Tagged 70's, Animation, Fantasy, Jules Verne, Karel Zeman, Psychedelic, Science Fiction, Surreal

2 Comments

Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969)

Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide gives Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969) two-and-a-half stars and a fragment of a sentence. Until the Warner Archives recently released the film on DVD, I had hardly heard of it before; but upon learning that Italian actress Luciana Paluzzi co-starred, I quickly sought it out. You see, I can trace when I hit puberty: it was when I saw Thunderball (1965), in particular when Paluzzi, sitting in a bathtub, asks James Bond if she could have something to put on (he hands her slippers). Also: the scene when James Bond sucks on Domino’s foot. Look, we all have to start somewhere. In what’s otherwise a pretty slow-paced 007 outing, Paluzzi easily walks away with the film, portraying Fiona Volpe, one of Bond’s most dangerous femme fatales, and certainly the sexiest. Wearing her leather assassin’s outfit, she drives a motorcycle equipped with a rocket launcher. She’d rather sleep with Bond than kill him, but either way she’d enjoy herself. That mix of glamour, animal sexuality, and killer instinct is irresistible in her performance. Alas, in Captain Nemo and the Underwater City she’s not an assassin, but rather a demure swimming coach (it’s true) caught between two square-jawed men. Still, she’s showcased lovingly: she tends to a flock of children in her swimming class with motherly grace; she elegantly leaps from a diving board during an exhibition; she even plays a theremin (!) while being filmed in soft focus. Paluzzi fans, please congregate – this isn’t to be missed.

Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide gives Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969) two-and-a-half stars and a fragment of a sentence. Until the Warner Archives recently released the film on DVD, I had hardly heard of it before; but upon learning that Italian actress Luciana Paluzzi co-starred, I quickly sought it out. You see, I can trace when I hit puberty: it was when I saw Thunderball (1965), in particular when Paluzzi, sitting in a bathtub, asks James Bond if she could have something to put on (he hands her slippers). Also: the scene when James Bond sucks on Domino’s foot. Look, we all have to start somewhere. In what’s otherwise a pretty slow-paced 007 outing, Paluzzi easily walks away with the film, portraying Fiona Volpe, one of Bond’s most dangerous femme fatales, and certainly the sexiest. Wearing her leather assassin’s outfit, she drives a motorcycle equipped with a rocket launcher. She’d rather sleep with Bond than kill him, but either way she’d enjoy herself. That mix of glamour, animal sexuality, and killer instinct is irresistible in her performance. Alas, in Captain Nemo and the Underwater City she’s not an assassin, but rather a demure swimming coach (it’s true) caught between two square-jawed men. Still, she’s showcased lovingly: she tends to a flock of children in her swimming class with motherly grace; she elegantly leaps from a diving board during an exhibition; she even plays a theremin (!) while being filmed in soft focus. Paluzzi fans, please congregate – this isn’t to be missed.

That all of this occurs in the 19th century world of Jules Verne may seem ridiculous, but suspend your disbelief, all ye who enter this film. This is, after all, the story of Captain Nemo (Robert Ryan) who rescues passengers from a sinking ship and transports them to his underwater colony, Templemere, a deep-sea Shangri-La that thrives upon inventions which can manufacture air, fresh water, and gold. So if you’re going to waste time ticking off every improbability, you’d best watch something else. (Anyway, to be generous, you could just call this steampunk. Because it does seem to have a steampunk aesthetic going on here.) Nemo is, in this outing, constructing his ideal Utopia beneath the waves, using his fabulous technology to meet every need of its hundreds of inhabitants, and hoping, in this manner, to outlive the humans on the surface, who threaten to annihilate all civilization with their endless wars. In other words, this is a Cold War film, and very much a post-Hiroshima reflection on the implication of weapons which can destroy the world; curiously, this film takes place before the atom was ever split, but Nemo cites that an explosion caused by his construction crew has mutated one of the mobula rays outside the city and caused it to grow to enormous size, Godzilla-style. Periodically it terrorizes the colony’s divers or Nemo’s famous Nautilus, which makes another welcome big-screen appearance.

That all of this occurs in the 19th century world of Jules Verne may seem ridiculous, but suspend your disbelief, all ye who enter this film. This is, after all, the story of Captain Nemo (Robert Ryan) who rescues passengers from a sinking ship and transports them to his underwater colony, Templemere, a deep-sea Shangri-La that thrives upon inventions which can manufacture air, fresh water, and gold. So if you’re going to waste time ticking off every improbability, you’d best watch something else. (Anyway, to be generous, you could just call this steampunk. Because it does seem to have a steampunk aesthetic going on here.) Nemo is, in this outing, constructing his ideal Utopia beneath the waves, using his fabulous technology to meet every need of its hundreds of inhabitants, and hoping, in this manner, to outlive the humans on the surface, who threaten to annihilate all civilization with their endless wars. In other words, this is a Cold War film, and very much a post-Hiroshima reflection on the implication of weapons which can destroy the world; curiously, this film takes place before the atom was ever split, but Nemo cites that an explosion caused by his construction crew has mutated one of the mobula rays outside the city and caused it to grow to enormous size, Godzilla-style. Periodically it terrorizes the colony’s divers or Nemo’s famous Nautilus, which makes another welcome big-screen appearance.

This was the third time Nemo’s submarine appeared on-screen, and naturally it’s a different design, now looking similar to a manta ray. Captain Nemo and the Underwater City followed Ray Harryhausen’s Mysterious Island (1961), and Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) before it, and fully expects that its audience will have seen at least one of those films, or, of course, read Jules Verne’s books. But it states its preference by casting Chuck Connors as the hero, Senator Robert Fraser; Connors bears a close physical likeness to Kirk Douglas of the Disney film. Similarly, two of his companions, the larcenous siblings Swallow and Barnaby, owe some slight lineage to Peter Lorre’s character in the original. And unlike Mysterious Island, this film takes place almost entirely underwater, in Nemo’s domain, spending plenty of time describing in Vernesian detail how a colony can thrive off the flora and fauna of the deeps. (Actually, if you were going to make these films a trilogy, you might want to stick this one in the middle. But I’d have to watch them all again to verify that makes some chronological sense.)

This was the third time Nemo’s submarine appeared on-screen, and naturally it’s a different design, now looking similar to a manta ray. Captain Nemo and the Underwater City followed Ray Harryhausen’s Mysterious Island (1961), and Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) before it, and fully expects that its audience will have seen at least one of those films, or, of course, read Jules Verne’s books. But it states its preference by casting Chuck Connors as the hero, Senator Robert Fraser; Connors bears a close physical likeness to Kirk Douglas of the Disney film. Similarly, two of his companions, the larcenous siblings Swallow and Barnaby, owe some slight lineage to Peter Lorre’s character in the original. And unlike Mysterious Island, this film takes place almost entirely underwater, in Nemo’s domain, spending plenty of time describing in Vernesian detail how a colony can thrive off the flora and fauna of the deeps. (Actually, if you were going to make these films a trilogy, you might want to stick this one in the middle. But I’d have to watch them all again to verify that makes some chronological sense.)

James Hill (Born Free) directs this time out, and does a respectable job, especially in his use of widescreen. But Robert Ryan – who starred in one of the best boxing films ever, The Set-Up (1949) – is unfortunately miscast as Captain Nemo. Granted, neither James Mason nor Herbert Lom lent Nemo the correct ethnicity (he’s from India), but they delivered gravitas; Ryan plays him as a grouchy, stern, and aging American, and it’s a hard sell. (Doubtless a big American star was sought to help market the film back in the States.) A solid supporting cast includes Nanette Newman (The Stepford Wives) as a pretty young mother who catches Nemo’s eye; Allan Cuthbertson (Performance) as a man driven to insanity by his claustrophobia; Paluzzi as the innocent but sensual Mala, who falls for Connors’ Senator Fraser; John Turner as Nemo’s second-in-command, the hand of the law until he’s finally undone by his unrequited love for Mala; and Bill Fraser (Up Pompeii) and Kenneth Connor (the Carry On films) as Barnaby and Swallow. Barnaby dresses like Captain Kangaroo, and Swallow like the Joker, so they pop out of every scene in bright primary colors. For a while, they’re also accompanied by overly “wacky” comic-relief music, which thankfully falls to the wayside as their characters grow more distinctive and interesting as the film progresses.

James Hill (Born Free) directs this time out, and does a respectable job, especially in his use of widescreen. But Robert Ryan – who starred in one of the best boxing films ever, The Set-Up (1949) – is unfortunately miscast as Captain Nemo. Granted, neither James Mason nor Herbert Lom lent Nemo the correct ethnicity (he’s from India), but they delivered gravitas; Ryan plays him as a grouchy, stern, and aging American, and it’s a hard sell. (Doubtless a big American star was sought to help market the film back in the States.) A solid supporting cast includes Nanette Newman (The Stepford Wives) as a pretty young mother who catches Nemo’s eye; Allan Cuthbertson (Performance) as a man driven to insanity by his claustrophobia; Paluzzi as the innocent but sensual Mala, who falls for Connors’ Senator Fraser; John Turner as Nemo’s second-in-command, the hand of the law until he’s finally undone by his unrequited love for Mala; and Bill Fraser (Up Pompeii) and Kenneth Connor (the Carry On films) as Barnaby and Swallow. Barnaby dresses like Captain Kangaroo, and Swallow like the Joker, so they pop out of every scene in bright primary colors. For a while, they’re also accompanied by overly “wacky” comic-relief music, which thankfully falls to the wayside as their characters grow more distinctive and interesting as the film progresses.

That’s the secret weapon of Captain Nemo and the Underwater City: the character development is understated but substantial, and you grow to care about these men and women – just as Nemo, gradually, learns to overcome his tyrannical impulses and form tentative relationships with them – before an escape plan is finally enacted, and Nemo reluctantly wages war against the escapees. Nemo, in many ways, is the film’s Prospero: an exile whose fearsome, unbending demeanor hiding a tenderness; which would make Mala his Miranda, falling in love with the first outsider she meets. This is a family matinee picture, but as an adult one can appreciate the moral ambiguities which the film refuses to resolve. The recurring question which the castaways ask of each other is whether they should stay, as Nemo demands, or escape; the allure of his Utopia is great, and really, there’s not much to dislike about Templemere. You get to sit poolside in a toga all day, while Nemo sees to your every need. Barnaby and Swallow hope to flee with a crate of stolen gold, until Swallow starts to have second thoughts: for him, to stay in the underwater city would be to chase contentment rather than greed. For Newman’s Helena, staying in Templemere offers a chance to rebuild family and home. But for Fraser, it’s a betrayal to his country; he needs to return to the United States since he’s carrying secret information which can prevent a war of vast destruction. He is willing to sacrifice his own happiness – a life with Mala – to save the lives of the people of the surface. There’s some meat in this screenplay, and it helps considerably…

That’s the secret weapon of Captain Nemo and the Underwater City: the character development is understated but substantial, and you grow to care about these men and women – just as Nemo, gradually, learns to overcome his tyrannical impulses and form tentative relationships with them – before an escape plan is finally enacted, and Nemo reluctantly wages war against the escapees. Nemo, in many ways, is the film’s Prospero: an exile whose fearsome, unbending demeanor hiding a tenderness; which would make Mala his Miranda, falling in love with the first outsider she meets. This is a family matinee picture, but as an adult one can appreciate the moral ambiguities which the film refuses to resolve. The recurring question which the castaways ask of each other is whether they should stay, as Nemo demands, or escape; the allure of his Utopia is great, and really, there’s not much to dislike about Templemere. You get to sit poolside in a toga all day, while Nemo sees to your every need. Barnaby and Swallow hope to flee with a crate of stolen gold, until Swallow starts to have second thoughts: for him, to stay in the underwater city would be to chase contentment rather than greed. For Newman’s Helena, staying in Templemere offers a chance to rebuild family and home. But for Fraser, it’s a betrayal to his country; he needs to return to the United States since he’s carrying secret information which can prevent a war of vast destruction. He is willing to sacrifice his own happiness – a life with Mala – to save the lives of the people of the surface. There’s some meat in this screenplay, and it helps considerably…

…because this film is, at times, terribly silly, from the alchemical devices which create too much gold for the colony to handle (they have a “scrap heap” filled with discarded items of gold), to the ringing alarms in the shapes of red lobsters, to the poorly-edited shark attack, to the Eloi-like, scantily-clad young women who hang about the pools, to the green “seaweed beer” they drink and, again, that scene in which Luciana Paluzzi plays the theremin, of all the instruments in the world. But some of the scale models are quite good, particularly the exterior shot of Templemere as the Nautilus first approaches, and the interior sets, where most of the action is staged, are beautifully designed. Later 70’s matinee fantasies, like anything starring Doug McClure, would look much cheaper, but Captain Nemo and the Underwater City is handsome and respectable. Leonard Maltin was at least half-a-star short. This one’s a pretty solid affair; and it does, I cannot understate, feature Fiona Volpe herself in a toga. Dubbed once more, but still.

…because this film is, at times, terribly silly, from the alchemical devices which create too much gold for the colony to handle (they have a “scrap heap” filled with discarded items of gold), to the ringing alarms in the shapes of red lobsters, to the poorly-edited shark attack, to the Eloi-like, scantily-clad young women who hang about the pools, to the green “seaweed beer” they drink and, again, that scene in which Luciana Paluzzi plays the theremin, of all the instruments in the world. But some of the scale models are quite good, particularly the exterior shot of Templemere as the Nautilus first approaches, and the interior sets, where most of the action is staged, are beautifully designed. Later 70’s matinee fantasies, like anything starring Doug McClure, would look much cheaper, but Captain Nemo and the Underwater City is handsome and respectable. Leonard Maltin was at least half-a-star short. This one’s a pretty solid affair; and it does, I cannot understate, feature Fiona Volpe herself in a toga. Dubbed once more, but still.

Posted in Theater Midnight Matinee

Tagged 60's, Fantasy, Jules Verne, Killer Shark, Luciana Paluzzi, Submarine, Utopia

Comments Off on Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969)