Is there anything which says “the 70’s” more succinctly than kung fu? Yes, there was the David Carradine series (1972-75); there were also comic books, like Marvel’s Master of Kung Fu (introduced in 1973); Peter Cushing pursued Dracula into Hong Kong in The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), joining forces with a team of kung fu fighters; James Bond dabbled in the martial art in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974); Carl Douglas sang about how everyone was kung fu fighting; and poorly-dubbed Hong Kong action films (from the Shaw Brothers and others) flooded American cinemas. At the nexus of this movement was Bruce Lee, in particular his film Enter the Dragon (1973). The American-born, Hong Kong-raised Lee was a competitive black belt fighter who had broken into Hollywood with his role as Kato on the short-lived Green Hornet series (1966-67). His film career was brief but stratospheric. After some dead ends in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong and starred in The Big Boss (1971), Fist of Fury (1972), and The Way of the Dragon (1972), which he wrote and directed (and which introduced the world to Chuck Norris). The substantial international grosses of these films caught Hollywood’s eye at last, and he was given the opportunity to star in Enter the Dragon, which would be co-financed by Warner Bros. Americans John Saxon (who had appeared on Kung Fu) and Jim Kelly (an African-American karate champion) would co-star alongside a predominantly Chinese cast.

Is there anything which says “the 70’s” more succinctly than kung fu? Yes, there was the David Carradine series (1972-75); there were also comic books, like Marvel’s Master of Kung Fu (introduced in 1973); Peter Cushing pursued Dracula into Hong Kong in The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974), joining forces with a team of kung fu fighters; James Bond dabbled in the martial art in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974); Carl Douglas sang about how everyone was kung fu fighting; and poorly-dubbed Hong Kong action films (from the Shaw Brothers and others) flooded American cinemas. At the nexus of this movement was Bruce Lee, in particular his film Enter the Dragon (1973). The American-born, Hong Kong-raised Lee was a competitive black belt fighter who had broken into Hollywood with his role as Kato on the short-lived Green Hornet series (1966-67). His film career was brief but stratospheric. After some dead ends in Hollywood, he returned to Hong Kong and starred in The Big Boss (1971), Fist of Fury (1972), and The Way of the Dragon (1972), which he wrote and directed (and which introduced the world to Chuck Norris). The substantial international grosses of these films caught Hollywood’s eye at last, and he was given the opportunity to star in Enter the Dragon, which would be co-financed by Warner Bros. Americans John Saxon (who had appeared on Kung Fu) and Jim Kelly (an African-American karate champion) would co-star alongside a predominantly Chinese cast.

To be honest, prior to this viewing, I don’t think I’d ever sat down and watched Enter the Dragon from beginning to end, though I’d seen most of it on television over the years. I was more closely familiar with “A Fistful of Yen,” in the John Landis/Zucker Brothers collaboration The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), which copies Enter the Dragon so closely that it becomes an uncanny act of mimicry as parody. Once you’ve seen that version, it’s hard to watch many scenes in Enter the Dragon with a straight face. That’s OK; the film is supposed to be over-the-top fun, and the good news is that it still holds up. Bruce Lee plays “Lee,” who, in the opening scenes, is studying Shaolin techniques among some Buddhist monks. When his master tells him, “You must remember, the enemy is only images and illusions, behind which he hides his true motives; destroy the image,” I was immediately certain that the climax would take place in a hall of mirrors. I was correct. Lee is quickly plucked away from this secluded paradise by Braithwaite (Geoffrey Weeks), a British-accented agent for an unnamed international organization that serves the needs of various world powers. In a very James Bond-y scene, he gives Lee a slideshow presentation to recruit him for a mission to destroy a drug and prostitution syndicate run by an evil overlord named Han (Kien Shih, a veteran of dozens of Hong Kong films). All Lee has to do is accept Han’s invitation to participate in a fighting tournament on his island fortress, then try to collect evidence of Han’s illicit activities. Lee’s suggestion that he simply shoot Han dead is quickly nixed by Braithwaite. Guns aren’t allowed on the island. Martial arts will need to be employed. Bruce Lee is fine with that.

To be honest, prior to this viewing, I don’t think I’d ever sat down and watched Enter the Dragon from beginning to end, though I’d seen most of it on television over the years. I was more closely familiar with “A Fistful of Yen,” in the John Landis/Zucker Brothers collaboration The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), which copies Enter the Dragon so closely that it becomes an uncanny act of mimicry as parody. Once you’ve seen that version, it’s hard to watch many scenes in Enter the Dragon with a straight face. That’s OK; the film is supposed to be over-the-top fun, and the good news is that it still holds up. Bruce Lee plays “Lee,” who, in the opening scenes, is studying Shaolin techniques among some Buddhist monks. When his master tells him, “You must remember, the enemy is only images and illusions, behind which he hides his true motives; destroy the image,” I was immediately certain that the climax would take place in a hall of mirrors. I was correct. Lee is quickly plucked away from this secluded paradise by Braithwaite (Geoffrey Weeks), a British-accented agent for an unnamed international organization that serves the needs of various world powers. In a very James Bond-y scene, he gives Lee a slideshow presentation to recruit him for a mission to destroy a drug and prostitution syndicate run by an evil overlord named Han (Kien Shih, a veteran of dozens of Hong Kong films). All Lee has to do is accept Han’s invitation to participate in a fighting tournament on his island fortress, then try to collect evidence of Han’s illicit activities. Lee’s suggestion that he simply shoot Han dead is quickly nixed by Braithwaite. Guns aren’t allowed on the island. Martial arts will need to be employed. Bruce Lee is fine with that.

What follows is essentially a 007 take on the martial arts film, complete with a megalomaniacal supervillain who has different weapon-attachments for his missing hand, and in one scene strokes a white cat. Once Lee arrives at the island headquarters, he sneaks out of his suite late at night, past the world’s worst guards, and through the world’s most poorly-hidden trap door (a few potted plants are set on top of it), to infiltrate Han’s drug cartel. He finds allies with fellow fight competitors Roper (Saxon) and Williams (Kelly). We learn that the tournament is actually just a recruitment tool for Han’s underworld empire, where the toughest and meanest will be given an opportunity to serve him. In the meantime, the fighters are allowed every luxury, including their choice of women from a harem that moves from one room to the next. Lee, of course, has too much body discipline to engage in sex, though he uses the opportunity to meet up with a beautiful spy planted by Braithwaite, and they exchange information. Jim Kelly chooses not one woman, but about half a dozen. John Saxon, even smoother, seduces the brothel’s madam.

What follows is essentially a 007 take on the martial arts film, complete with a megalomaniacal supervillain who has different weapon-attachments for his missing hand, and in one scene strokes a white cat. Once Lee arrives at the island headquarters, he sneaks out of his suite late at night, past the world’s worst guards, and through the world’s most poorly-hidden trap door (a few potted plants are set on top of it), to infiltrate Han’s drug cartel. He finds allies with fellow fight competitors Roper (Saxon) and Williams (Kelly). We learn that the tournament is actually just a recruitment tool for Han’s underworld empire, where the toughest and meanest will be given an opportunity to serve him. In the meantime, the fighters are allowed every luxury, including their choice of women from a harem that moves from one room to the next. Lee, of course, has too much body discipline to engage in sex, though he uses the opportunity to meet up with a beautiful spy planted by Braithwaite, and they exchange information. Jim Kelly chooses not one woman, but about half a dozen. John Saxon, even smoother, seduces the brothel’s madam.

Enter the Dragon constantly intercuts between these three characters, so that it comes closer to an ensemble piece like The Dirty Dozen. Since Saxon and Kelly are so likable (actually, much more enjoyable to watch as actors than Lee), the film becomes even more engaging. Though we learn that Roper and Williams fought in Vietnam together, they don’t have many scenes where they can chat. All three of our central characters hardly talk to each other, for Han keeps his fighters separated. They develop their bond mostly through their eyes, casting glances from across the fighters’ circles, first in curiosity or humor, and eventually into loyalty. In one of the film’s funniest moments, Williams silently urges Roper to keep losing to his challenger, so that he can reap more winnings on his bet before Roper can finally start fighting back. Watch Kelly and Saxon sell this scene with no dialogue – they’re both fantastic.

Enter the Dragon constantly intercuts between these three characters, so that it comes closer to an ensemble piece like The Dirty Dozen. Since Saxon and Kelly are so likable (actually, much more enjoyable to watch as actors than Lee), the film becomes even more engaging. Though we learn that Roper and Williams fought in Vietnam together, they don’t have many scenes where they can chat. All three of our central characters hardly talk to each other, for Han keeps his fighters separated. They develop their bond mostly through their eyes, casting glances from across the fighters’ circles, first in curiosity or humor, and eventually into loyalty. In one of the film’s funniest moments, Williams silently urges Roper to keep losing to his challenger, so that he can reap more winnings on his bet before Roper can finally start fighting back. Watch Kelly and Saxon sell this scene with no dialogue – they’re both fantastic.

As for Lee, he’s the lone wolf, so as viewers we tend to pay attention because – until the film’s climax – he’s typically fighting dozens of enemies all on his own. Bruce Lee choreographed the fight scenes, as you’d expect, and director Robert Clouse, whose most famous film this is, does the right thing and keeps his camera pulled back, for the most part, so you can see Lee’s arms and legs as they snap out and paralyze his opponents. (One of the chief complaints you hear about action films these days is that they’re cut incoherently. Enter the Dragon is a lesson on how a fight scene should be shot.) The most iconic images of Enter the Dragon are those shot in slow-motion, as Lee strikes a pose after cutting his adversary down and snapping their neck with his foot (off-camera). Lee’s expression is agonized (and, as my wife observes, he bawks like a chicken). The music, by Lalo Schifrin, has been 70’s-funk-fantastic so far, but in these moments it suddenly becomes chilling-horror-movie. The message seems to be: Lee can be a terrifying killer. Do not fuck with Bruce Lee.

Well, it worked. After Enter the Dragon became a sleeper hit, Bruce Lee tee-shirts (usually with him striking that same agonized look) and posters were commonplace. Kung fu, which was simmering before, exploded into a phenomenon, and Lee was its central celebrity. Tragically, he wasn’t around to enjoy it. Lee died on July 20, 1973, from cerebral edema (though conspiracy theories have floated about for decades). His death was still in the papers when the film premiered, and couldn’t have hurt its box office. (Brandon Lee, Bruce’s son, died in a stunt accident while shooting the Goth-superhero film The Crow in 1993; comparisons to his father’s death were inevitably drawn, and the notion of a “curse” was entertained.) But Bruce Lee was too big of a star to stay dead. Eventually, his incomplete film Game of Death was finished (in 1978) by Robert Clouse with lookalikes to support the sparse usable footage of Lee. (It’s hard not to think of 1982’s Trail of the Pink Panther, which patched together a Peter Sellers Pink Panther film despite its star’s death.) And there were the imitators – a flood of them. The Wikipedia entry for “Brucesploitation” lists the pseudonyms of actors hired to play Bruce Lee-styled roles: Bruce Li, Bruce Le, Bronson Lee, Bruce Lei, Bruce Lie, Lee Bruce, and Dragon Lee among them. Then there’s the case of The Clones of Bruce Lee (1981), in which the actor is…well, read the title. This is surely a future Midnight Only entry.

Well, it worked. After Enter the Dragon became a sleeper hit, Bruce Lee tee-shirts (usually with him striking that same agonized look) and posters were commonplace. Kung fu, which was simmering before, exploded into a phenomenon, and Lee was its central celebrity. Tragically, he wasn’t around to enjoy it. Lee died on July 20, 1973, from cerebral edema (though conspiracy theories have floated about for decades). His death was still in the papers when the film premiered, and couldn’t have hurt its box office. (Brandon Lee, Bruce’s son, died in a stunt accident while shooting the Goth-superhero film The Crow in 1993; comparisons to his father’s death were inevitably drawn, and the notion of a “curse” was entertained.) But Bruce Lee was too big of a star to stay dead. Eventually, his incomplete film Game of Death was finished (in 1978) by Robert Clouse with lookalikes to support the sparse usable footage of Lee. (It’s hard not to think of 1982’s Trail of the Pink Panther, which patched together a Peter Sellers Pink Panther film despite its star’s death.) And there were the imitators – a flood of them. The Wikipedia entry for “Brucesploitation” lists the pseudonyms of actors hired to play Bruce Lee-styled roles: Bruce Li, Bruce Le, Bronson Lee, Bruce Lei, Bruce Lie, Lee Bruce, and Dragon Lee among them. Then there’s the case of The Clones of Bruce Lee (1981), in which the actor is…well, read the title. This is surely a future Midnight Only entry.

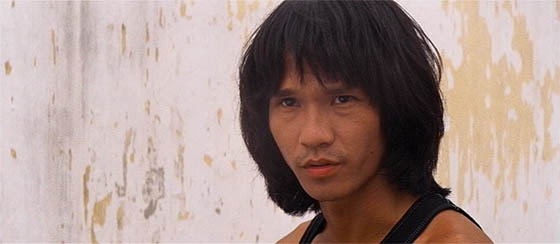

But for the second half of our double feature tonight we visit Challenge of the Tiger (1980), starring Bruce Le, and a few years ago released on DVD as the B-picture on a double bill with For Your Height Only (1981), which I tackled last week. The first thing I noticed while watching this particular relic of Brucesploitation is that, seven years on from Enter the Dragon, it’s still for some reason important to borrow liberally from that film. One of the first scenes is another slideshow, in which two CIA operatives discuss the premise (presumably so we can get this out of the way, and move on to some fight scenes). But Challenge of the Tiger provides a real topper: this isn’t some drug syndicate that needs to be unraveled; rather, an evil organization has stolen a secret formula for killing sperm. In the film’s prologue, we see the two scientists just after their discovery has been made. “Imagine if this were to fall into the wrong hands,” says one, seconds before masked gunmen burst into the laboratory and slaughter them, stealing the formula. Few know this, but spermicide was rare and precious in 1980, and in fact was the main reason the Cold War stretched for another eleven years.

But for the second half of our double feature tonight we visit Challenge of the Tiger (1980), starring Bruce Le, and a few years ago released on DVD as the B-picture on a double bill with For Your Height Only (1981), which I tackled last week. The first thing I noticed while watching this particular relic of Brucesploitation is that, seven years on from Enter the Dragon, it’s still for some reason important to borrow liberally from that film. One of the first scenes is another slideshow, in which two CIA operatives discuss the premise (presumably so we can get this out of the way, and move on to some fight scenes). But Challenge of the Tiger provides a real topper: this isn’t some drug syndicate that needs to be unraveled; rather, an evil organization has stolen a secret formula for killing sperm. In the film’s prologue, we see the two scientists just after their discovery has been made. “Imagine if this were to fall into the wrong hands,” says one, seconds before masked gunmen burst into the laboratory and slaughter them, stealing the formula. Few know this, but spermicide was rare and precious in 1980, and in fact was the main reason the Cold War stretched for another eleven years.

To retrieve the formula, the CIA summons its best agents, Huang Lung (Bruce Le) and Richard Cannon (Richard Harrison). Now, I ask you: if you are going to name a character “Richard Cannon,” why have all the characters just call him “Richard” through the entire film? I wanted him to demand, “My name is Cannon. Cannon!” He never does this. But forget Bruce Le, Richard Harrison is the star of this film. Let me describe his introduction: as he pulls his convertible through the gates of his estate, he’s greeted by two topless women. “Let’s go change now,” says the large-breasted girl; this does not happen. The next shot is of her playing topless tennis in slow motion, which could, for women, be a very convincing sports bra commercial. We learn that topless tennis requires two topless girls standing on either side of the court to retrieve the ball; Wimbledon rules, I think. As Richard relaxes with his nude harem by the pool, he receives a call on his solid-gold phone. A formula for killing sperm? Masculine Man springs into action.

To retrieve the formula, the CIA summons its best agents, Huang Lung (Bruce Le) and Richard Cannon (Richard Harrison). Now, I ask you: if you are going to name a character “Richard Cannon,” why have all the characters just call him “Richard” through the entire film? I wanted him to demand, “My name is Cannon. Cannon!” He never does this. But forget Bruce Le, Richard Harrison is the star of this film. Let me describe his introduction: as he pulls his convertible through the gates of his estate, he’s greeted by two topless women. “Let’s go change now,” says the large-breasted girl; this does not happen. The next shot is of her playing topless tennis in slow motion, which could, for women, be a very convincing sports bra commercial. We learn that topless tennis requires two topless girls standing on either side of the court to retrieve the ball; Wimbledon rules, I think. As Richard relaxes with his nude harem by the pool, he receives a call on his solid-gold phone. A formula for killing sperm? Masculine Man springs into action.

Now, Bruce Le. The chief difference between Bruce Lee and Bruce Le, it seems, is that Le is constantly in motion. I don’t necessarily mean this as a compliment. Action scenes fall his way every few minutes, forcing him into a fight each time he steps into the street. There is no logic behind it; rather, a few minutes have passed without a fight scene, so with no rhyme or reason, thugs will suddenly surround him, and off Le goes like a hurricane. His rapid-fire fighting techniques are well choreographed, though there’s little actual excitement, since no suspense has been developed whatsoever. In one ridiculous scene, Bruce Le and Richard Harrison fight with motorcyclists while standing on some outdoor steps. The motorcycles come at them from above and Le and Harrison are alarmed, and do their best to fight them off. Then the motorcycles come from below, and even though they’re traveling at about 5 MPH and awkwardly bumbling back up the steps, Le and Harrison remain in fighting stance, with the same look of alarm. I suppose Le’s showcase moment comes in a bullfighting ring in Spain. A hat containing the spermicide formula is thrust into the air, and Le grabs it and fights off his opponents to retain possession, eventually finding himself in the center of the ring and cornered by the bull (which, in close-ups, is a fake). Le karate-chops and splits the bull’s skull, which is illustrated by the director flashing a drawing of a bull’s head on the screen, and an animated crack running down it. (PETA has no jurisdiction over animation.)

Now, Bruce Le. The chief difference between Bruce Lee and Bruce Le, it seems, is that Le is constantly in motion. I don’t necessarily mean this as a compliment. Action scenes fall his way every few minutes, forcing him into a fight each time he steps into the street. There is no logic behind it; rather, a few minutes have passed without a fight scene, so with no rhyme or reason, thugs will suddenly surround him, and off Le goes like a hurricane. His rapid-fire fighting techniques are well choreographed, though there’s little actual excitement, since no suspense has been developed whatsoever. In one ridiculous scene, Bruce Le and Richard Harrison fight with motorcyclists while standing on some outdoor steps. The motorcycles come at them from above and Le and Harrison are alarmed, and do their best to fight them off. Then the motorcycles come from below, and even though they’re traveling at about 5 MPH and awkwardly bumbling back up the steps, Le and Harrison remain in fighting stance, with the same look of alarm. I suppose Le’s showcase moment comes in a bullfighting ring in Spain. A hat containing the spermicide formula is thrust into the air, and Le grabs it and fights off his opponents to retain possession, eventually finding himself in the center of the ring and cornered by the bull (which, in close-ups, is a fake). Le karate-chops and splits the bull’s skull, which is illustrated by the director flashing a drawing of a bull’s head on the screen, and an animated crack running down it. (PETA has no jurisdiction over animation.)

As for the villains, at one point in the movie they retrieve the spermicide and promptly exchange the Nazi salute, so I guess they’re pretty evil. The chief villain is a puny little guy with the kind of beard one manages to grow at the age of sixteen; at one point, he takes down his most muscular fighter, punishing him for his failure, and it’s a pretty unconvincing battle. His most loyal underlings are a female assassin, who takes a bubble bath with Harrison, and a bodybuilder with a striking resemblance to Lou Reed. (I encourage you to pretend that it really is Lou Reed. It helps.) The villain’s final battle with Le is pretty underwhelming, though it does end with a car veering off a cliff and exploding, which is always essential. Le co-wrote the screenplay with someone named Poon Fan, and I would like to remind you that silly names aren’t funny.

As for the villains, at one point in the movie they retrieve the spermicide and promptly exchange the Nazi salute, so I guess they’re pretty evil. The chief villain is a puny little guy with the kind of beard one manages to grow at the age of sixteen; at one point, he takes down his most muscular fighter, punishing him for his failure, and it’s a pretty unconvincing battle. His most loyal underlings are a female assassin, who takes a bubble bath with Harrison, and a bodybuilder with a striking resemblance to Lou Reed. (I encourage you to pretend that it really is Lou Reed. It helps.) The villain’s final battle with Le is pretty underwhelming, though it does end with a car veering off a cliff and exploding, which is always essential. Le co-wrote the screenplay with someone named Poon Fan, and I would like to remind you that silly names aren’t funny.

Challenge of the Tiger doesn’t have much of distinction, though it tries to simulate the Bruce Lee/John Saxon brothers-in-battle relationship of Enter the Dragon. Whether or not it succeeds in any measure depends on how much pleasure you get out of watching a film in which a little manic guy is always fighting, and his taller, mustachioed friend is constantly chasing tail. Enter the Dragon, on the other hand, still makes it plain how such a strange phenomenon as Brucesploitation could ever occur. It’s pretty damn good.

So here is a musical science-fiction fantasy filmed in black-and-white with color sequences, produced by Lorne Michaels, featuring appearances by Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd the same year they made Ghostbusters, written and directed by Saturday Night Live writer Tom Schilling in a manner which pays homage to Fritz Lang, Sergei Eisenstein, and 1930’s musical comedies. Do I have your attention? Nothing Lasts Forever (1984) has never been released on home video, and although Bill Murray introduced a special screening of the film in Brooklyn in 2004, it’s since drifted back to dormancy. The film deserves better; it’s not a lost masterpiece, but its obscurity is criminal.

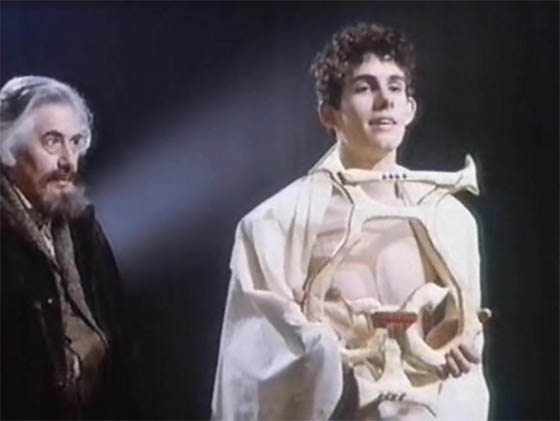

So here is a musical science-fiction fantasy filmed in black-and-white with color sequences, produced by Lorne Michaels, featuring appearances by Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd the same year they made Ghostbusters, written and directed by Saturday Night Live writer Tom Schilling in a manner which pays homage to Fritz Lang, Sergei Eisenstein, and 1930’s musical comedies. Do I have your attention? Nothing Lasts Forever (1984) has never been released on home video, and although Bill Murray introduced a special screening of the film in Brooklyn in 2004, it’s since drifted back to dormancy. The film deserves better; it’s not a lost masterpiece, but its obscurity is criminal. Tom Schilling’s film is a fairy tale, and obviously a very personal project, but it draws upon its influences, sorts through them, and spits them back out in strangely reconfigured shapes. It’s what you would call a movie-movie; it basks in the glow of cinephelia. A young Zach Galligan (Gremlins) plays the bright-eyed, good-hearted Adam Beckett, who, at the movie’s start, is playing Chopin on piano at Carnegie Hall. He’s humiliated, Milli-Vanilli style, when it proves to be a player piano, exposing him as a fraud. (A bearded prospector in long underwear, holding a rifle in his hands, stands up in the audience and shouts accusingly, “It’s a player pian-ey! He’s a fake! Get ‘im!”) New York’s finely-tailored upper crust storm the stage, gut the piano of its “music rolls,” and wrap Adam up in them like a mummy. He then awakens from his nightmare, covered in sweat, though it should be noted that the rest of this film plays just as dream-like, with no discernable contrast from what’s just transpired. He’s on a train in Europe sitting across from a Swedish architect, and when Adam confesses his self-doubt, and his longings to be a true artist, the architect encourages him to go to New York to pursue his dream. “I want you to know one thing,” he tells Adam. “You will get everything you want in your lifetime, only you won’t get it the way you expect.”

Tom Schilling’s film is a fairy tale, and obviously a very personal project, but it draws upon its influences, sorts through them, and spits them back out in strangely reconfigured shapes. It’s what you would call a movie-movie; it basks in the glow of cinephelia. A young Zach Galligan (Gremlins) plays the bright-eyed, good-hearted Adam Beckett, who, at the movie’s start, is playing Chopin on piano at Carnegie Hall. He’s humiliated, Milli-Vanilli style, when it proves to be a player piano, exposing him as a fraud. (A bearded prospector in long underwear, holding a rifle in his hands, stands up in the audience and shouts accusingly, “It’s a player pian-ey! He’s a fake! Get ‘im!”) New York’s finely-tailored upper crust storm the stage, gut the piano of its “music rolls,” and wrap Adam up in them like a mummy. He then awakens from his nightmare, covered in sweat, though it should be noted that the rest of this film plays just as dream-like, with no discernable contrast from what’s just transpired. He’s on a train in Europe sitting across from a Swedish architect, and when Adam confesses his self-doubt, and his longings to be a true artist, the architect encourages him to go to New York to pursue his dream. “I want you to know one thing,” he tells Adam. “You will get everything you want in your lifetime, only you won’t get it the way you expect.” He returns to New York City to find it paralyzed by a bus-driver’s strike and an influx of immigrants from Los Angeles, which has been leveled by a massive earthquake. To restore order, the New York Port Authority has taken over the city like a fascist regime. All of this back-story, by the way, is told with found stock footage that meshes fairly seamlessly with the grainy black-and-white that dominates the film. In that manner, it’s reminiscent of Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, the Carl Reiner film from two years earlier which convincingly placed Steve Martin into old film noirs. Similarly, Nothing Lasts Forever has the look of an early-30’s studio picture. Sets occasionally call to mind Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936), although the New York Schilling presents is set neither in the distant past nor in the far future (an apt comparison would be Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, dystopian but cluttered with relics of the past). Adam applies with the Port Authority to be an artist, which sends him to an office building where he’s asked to fill out some forms and submit to an “artist’s test”: he’s thrust into a small chamber where a woman doffs her clothes, and he must complete a life drawing within about thirty seconds. His work is deemed unsuitable, so he’s transferred to the Holland Tunnel, where he monitors traffic under the supervision of a no-nonsense Dan Aykroyd.

He returns to New York City to find it paralyzed by a bus-driver’s strike and an influx of immigrants from Los Angeles, which has been leveled by a massive earthquake. To restore order, the New York Port Authority has taken over the city like a fascist regime. All of this back-story, by the way, is told with found stock footage that meshes fairly seamlessly with the grainy black-and-white that dominates the film. In that manner, it’s reminiscent of Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, the Carl Reiner film from two years earlier which convincingly placed Steve Martin into old film noirs. Similarly, Nothing Lasts Forever has the look of an early-30’s studio picture. Sets occasionally call to mind Metropolis (1927) and Things to Come (1936), although the New York Schilling presents is set neither in the distant past nor in the far future (an apt comparison would be Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, dystopian but cluttered with relics of the past). Adam applies with the Port Authority to be an artist, which sends him to an office building where he’s asked to fill out some forms and submit to an “artist’s test”: he’s thrust into a small chamber where a woman doffs her clothes, and he must complete a life drawing within about thirty seconds. His work is deemed unsuitable, so he’s transferred to the Holland Tunnel, where he monitors traffic under the supervision of a no-nonsense Dan Aykroyd. One of his co-workers is a German girl named Mara (Apollonia van Ravenstein), and when he follows her to the joint where she spends her free time (think: Andy Warhol’s Factory recycled through an early Duran Duran video), he discovers that being a hardcore artist in New York means taking yourself very, very seriously. Television monitors show the eye-slitting scene from Un Chien Andalou. A shirtless German man marches on a treadmill while counting his steps, and an audience pays rapt attention. Mara gives Adam a book on Dadaism for him to study like homework. They have sex, but she interrupts her orgasm when she sees that Battleship Potemkin is playing on her tiny, tiny television set (it’s much like viewing great cinema on an iPhone; appropriately, Adam complains). But in his spare time, he drifts off to Carnegie Hall to look longingly through its doors, and there meets a bum named Hugo. They discuss Adam’s dreams of being an artist, and he offers food and shelter, which Hugo politely declines. Still, this moment of kindness reaps an unexpected reward. Some time later Hugo visits Adam in the Holland Tunnel and urges him to follow immediately. Hugo, it seems, is part of a secret society of hobos; as they pass through a portal and journey beneath the city, Hugo reveals that all of New York is a dream controlled by a greater intelligence. They organize and manipulate the souls of its citizens, which take the form of ticker tape.

One of his co-workers is a German girl named Mara (Apollonia van Ravenstein), and when he follows her to the joint where she spends her free time (think: Andy Warhol’s Factory recycled through an early Duran Duran video), he discovers that being a hardcore artist in New York means taking yourself very, very seriously. Television monitors show the eye-slitting scene from Un Chien Andalou. A shirtless German man marches on a treadmill while counting his steps, and an audience pays rapt attention. Mara gives Adam a book on Dadaism for him to study like homework. They have sex, but she interrupts her orgasm when she sees that Battleship Potemkin is playing on her tiny, tiny television set (it’s much like viewing great cinema on an iPhone; appropriately, Adam complains). But in his spare time, he drifts off to Carnegie Hall to look longingly through its doors, and there meets a bum named Hugo. They discuss Adam’s dreams of being an artist, and he offers food and shelter, which Hugo politely declines. Still, this moment of kindness reaps an unexpected reward. Some time later Hugo visits Adam in the Holland Tunnel and urges him to follow immediately. Hugo, it seems, is part of a secret society of hobos; as they pass through a portal and journey beneath the city, Hugo reveals that all of New York is a dream controlled by a greater intelligence. They organize and manipulate the souls of its citizens, which take the form of ticker tape. The journey beneath New York also marks a transition from black-and-white to color, Wizard of Oz-like, and the pale hues call to mind color films of the 1940’s. That is, even in color, Nothing Lasts Forever resists the look of 1984. It still looks like a lost artifact recovered from a celluloid vault. In the secret city, Adam is cleaned and washed by old, semi-nude men, and delivered in a toga to a command chamber where he meets Father Knickerbocker (veteran character actor Sam Jaffe, who died the year this was released). He’s told that because he’s pure of heart and dreams of being a true artist, he has been selected to achieve his dreams. He’ll journey to the Moon and meet his true love, named Eloy. The hows and the whys are sketchy.

The journey beneath New York also marks a transition from black-and-white to color, Wizard of Oz-like, and the pale hues call to mind color films of the 1940’s. That is, even in color, Nothing Lasts Forever resists the look of 1984. It still looks like a lost artifact recovered from a celluloid vault. In the secret city, Adam is cleaned and washed by old, semi-nude men, and delivered in a toga to a command chamber where he meets Father Knickerbocker (veteran character actor Sam Jaffe, who died the year this was released). He’s told that because he’s pure of heart and dreams of being a true artist, he has been selected to achieve his dreams. He’ll journey to the Moon and meet his true love, named Eloy. The hows and the whys are sketchy. He does make it to the Moon, though not through any effort on his part. After running through a rainy, empty street at night, he takes shelter in a bus occupied by senior citizens. It quickly becomes apparent that they’re on a trip which he’s interrupted, much to the consternation of their tour director, played by Bill Murray. It’s no ordinary bus, as he quickly learns: Murray and a flight attendant tell the passengers to extinguish their cigarettes and buckle their seat belts, and instructions are given on operating the oxygen masks overhead, “in case of emergency.” The bus launches its rockets and soars off the road and above New York City, eventually escaping Earth’s atmosphere, in some deliberately retro FX. (Both the Earth and the Moon are supposed to look that two-dimensional.) When he’s free to move about the cabin, Adam quickly learns that, like the TARDIS, the bus is larger on the inside than the outside. There’s a lounge where cocktails are served and Eddie Fisher performs. (“How the hell did I end up singing on a bus to the Moon?” “Must’ve been all those women, Mr. Fisher.”) Adam talks to one Daisy Schackman (Imogene Coca), who explains that the elderly visit the Moon all the time, only chips implanted in the backs of their necks (X-Files style) force them to say the word “Miami” instead of “The Moon.” The government also postmarks all the vacationers’ correspondence from Florida, to keep up the ruse.

He does make it to the Moon, though not through any effort on his part. After running through a rainy, empty street at night, he takes shelter in a bus occupied by senior citizens. It quickly becomes apparent that they’re on a trip which he’s interrupted, much to the consternation of their tour director, played by Bill Murray. It’s no ordinary bus, as he quickly learns: Murray and a flight attendant tell the passengers to extinguish their cigarettes and buckle their seat belts, and instructions are given on operating the oxygen masks overhead, “in case of emergency.” The bus launches its rockets and soars off the road and above New York City, eventually escaping Earth’s atmosphere, in some deliberately retro FX. (Both the Earth and the Moon are supposed to look that two-dimensional.) When he’s free to move about the cabin, Adam quickly learns that, like the TARDIS, the bus is larger on the inside than the outside. There’s a lounge where cocktails are served and Eddie Fisher performs. (“How the hell did I end up singing on a bus to the Moon?” “Must’ve been all those women, Mr. Fisher.”) Adam talks to one Daisy Schackman (Imogene Coca), who explains that the elderly visit the Moon all the time, only chips implanted in the backs of their necks (X-Files style) force them to say the word “Miami” instead of “The Moon.” The government also postmarks all the vacationers’ correspondence from Florida, to keep up the ruse. You see, a colony has been established on the Moon since the 1950’s, and it now serves as both a shopping mall and a tourist trap. The original lunar inhabitants have been subjugated and forced to work for the colonists. They greet the arrivals with some hula dancing, while Bill Murray translates the meaning of the dance. Foremost among them is the girl for whom Adam is predestined, Eloy, played by Lauren Tom. Yes, the same Lauren Tom who voices Amy Wong on Futurama, which, in its first season, also portrayed the Moon as a giant tourist trap. So go ahead and pretend that Zach Galligan is Fry, and this is a live-action version of Futurama; knock yourself out. The Moon is so cartoonish that it would encourage such an interpretation; it looks like it was inspired by “Marvin the Martian” shorts. It’s an obvious set, with a deliberately flat backdrop. To see the bus pull up on the set, before the waiting hula dancers (who have small antennae upon their heads), and the senior citizens pile out wearing their New Wave-ish “lunar glasses” – including one ecstatic Larry “Bud” Melman – really just makes the whole film worthwhile. I scribbled down a number of movie titles while watching this, and one of them was Forbidden Zone. An Oingo Boingo score would seem appropriate.

You see, a colony has been established on the Moon since the 1950’s, and it now serves as both a shopping mall and a tourist trap. The original lunar inhabitants have been subjugated and forced to work for the colonists. They greet the arrivals with some hula dancing, while Bill Murray translates the meaning of the dance. Foremost among them is the girl for whom Adam is predestined, Eloy, played by Lauren Tom. Yes, the same Lauren Tom who voices Amy Wong on Futurama, which, in its first season, also portrayed the Moon as a giant tourist trap. So go ahead and pretend that Zach Galligan is Fry, and this is a live-action version of Futurama; knock yourself out. The Moon is so cartoonish that it would encourage such an interpretation; it looks like it was inspired by “Marvin the Martian” shorts. It’s an obvious set, with a deliberately flat backdrop. To see the bus pull up on the set, before the waiting hula dancers (who have small antennae upon their heads), and the senior citizens pile out wearing their New Wave-ish “lunar glasses” – including one ecstatic Larry “Bud” Melman – really just makes the whole film worthwhile. I scribbled down a number of movie titles while watching this, and one of them was Forbidden Zone. An Oingo Boingo score would seem appropriate. Instead, the score is lush and romantic. It’s by Howard Shore, another SNL veteran, who would later become one of our most esteemed film composers thanks to Lord of the Rings. His theme is based upon Chopin, and also the film’s theme song “Nothing Lasts Forever,” which is delivered by Eloy and Adam when they meet and fall in love in her little lunar villa. Lauren Tom is dubbed, and reaches some pretty high notes. (Anita Ellis, who plays Adam’s Aunt Anita, also gets to sing a number in an early party scene.) The stay on the Moon is short, though there are some funny bits involving its rampant commercialization; pretty soon Bill Murray punches Adam in the face, and he wakes up back in New York City. But it’s not a dream, he’s told – and he needs to get to Carnegie Hall for his debut performance.

Instead, the score is lush and romantic. It’s by Howard Shore, another SNL veteran, who would later become one of our most esteemed film composers thanks to Lord of the Rings. His theme is based upon Chopin, and also the film’s theme song “Nothing Lasts Forever,” which is delivered by Eloy and Adam when they meet and fall in love in her little lunar villa. Lauren Tom is dubbed, and reaches some pretty high notes. (Anita Ellis, who plays Adam’s Aunt Anita, also gets to sing a number in an early party scene.) The stay on the Moon is short, though there are some funny bits involving its rampant commercialization; pretty soon Bill Murray punches Adam in the face, and he wakes up back in New York City. But it’s not a dream, he’s told – and he needs to get to Carnegie Hall for his debut performance. In many ways, Nothing Lasts Forever is a slight film. The stream-of-consciousness plot is inconsequential, and never really generates substantial conflict or momentum. It’s a paper-thin fable that doesn’t quite make it to 80 minutes, and doesn’t have anything of great profundity to impart. In other words, it could have been a short; and given how seldom it’s been screened, it might as well have been. But in many ways the film is a revelation. It prefigures the work of Guy Maddin (the color sequences look like his film Careful, and the storytelling, though lighter on the sexual repression, is of a retro-fabulist nature akin to Maddin’s many works). It’s visually striking continuously, from its German Expressionist interpretation of the Big Apple, to a Moon suited to Georges Méliès. The humor is gentle, for everything is glossed in nostalgia. That so much of the cast is peppered with familiar faces from yesteryear is central to the film’s recurring theme of the old being unduly ignored and pushed aside. In Tom Schilling’s imagination, the old, downtrodden bums are really powerful mystics controlling the Fates; and your grandparents aren’t going to Miami, but to the Moon no less, if only they could tell you. Similarly, he rescues the outdated styles of the films of yesteryear, which are even more remote today. Now if only someone could rescue Nothing Lasts Forever. I would expect that in 2011 it would find a wider and more appreciative audience than it did in 1984.

In many ways, Nothing Lasts Forever is a slight film. The stream-of-consciousness plot is inconsequential, and never really generates substantial conflict or momentum. It’s a paper-thin fable that doesn’t quite make it to 80 minutes, and doesn’t have anything of great profundity to impart. In other words, it could have been a short; and given how seldom it’s been screened, it might as well have been. But in many ways the film is a revelation. It prefigures the work of Guy Maddin (the color sequences look like his film Careful, and the storytelling, though lighter on the sexual repression, is of a retro-fabulist nature akin to Maddin’s many works). It’s visually striking continuously, from its German Expressionist interpretation of the Big Apple, to a Moon suited to Georges Méliès. The humor is gentle, for everything is glossed in nostalgia. That so much of the cast is peppered with familiar faces from yesteryear is central to the film’s recurring theme of the old being unduly ignored and pushed aside. In Tom Schilling’s imagination, the old, downtrodden bums are really powerful mystics controlling the Fates; and your grandparents aren’t going to Miami, but to the Moon no less, if only they could tell you. Similarly, he rescues the outdated styles of the films of yesteryear, which are even more remote today. Now if only someone could rescue Nothing Lasts Forever. I would expect that in 2011 it would find a wider and more appreciative audience than it did in 1984.