In the years prior to The Little Mermaid (1989), Disney was adrift, not sure exactly what kind of movie it should be making. In the same year that the studio produced a dark but unfocused animated fantasy (The Black Cauldron), they released Return to Oz (1985), a live-action sequel to The Wizard of Oz (1939) which would open with Dorothy being delivered by Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to a quack doctor for electroshock therapy treatment in hopes of “curing” the girl of those Oz fantasies she holds so dear. Yes, Disney thought this was a great idea for a big budget children’s movie. But kids are more mature than they seem, right? Listen – ask anyone of my generation what they remember about Return to Oz and you will get the same answer: “Oh! God! Electroshock therapy!” Walt Disney Studios apparently wanted into the nightmare business.

In the years prior to The Little Mermaid (1989), Disney was adrift, not sure exactly what kind of movie it should be making. In the same year that the studio produced a dark but unfocused animated fantasy (The Black Cauldron), they released Return to Oz (1985), a live-action sequel to The Wizard of Oz (1939) which would open with Dorothy being delivered by Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to a quack doctor for electroshock therapy treatment in hopes of “curing” the girl of those Oz fantasies she holds so dear. Yes, Disney thought this was a great idea for a big budget children’s movie. But kids are more mature than they seem, right? Listen – ask anyone of my generation what they remember about Return to Oz and you will get the same answer: “Oh! God! Electroshock therapy!” Walt Disney Studios apparently wanted into the nightmare business.

I saw this film in the theater when I was nine years old. All I knew of Oz was the original film, which we watched, like every family’s ritual, once a year. Return to Oz transfixed me for its entire two-hour running time. I paid absolute attention. Because if a children’s story decides to be a little dark, a little unusual, a little unpredictable, a child’s brain will react. I suppose the Brothers Grimm figured this out a long time ago. I don’t believe I had any nightmares afterward, and I was certainly not terrified or traumatized – however very uneasy those early scenes in the clinic made me – but these decades later all I know is that I sought out the Oz books afterward, and started reading through them voraciously, which is not what you would call a negative reaction. I’m reading the Oz books again now, and doing so brought me back to this film which I hadn’t seen since I was nine. I was surprised at how vividly these scenes came back to me. This film was imprinted upon me. Disney should be more careful.

I saw this film in the theater when I was nine years old. All I knew of Oz was the original film, which we watched, like every family’s ritual, once a year. Return to Oz transfixed me for its entire two-hour running time. I paid absolute attention. Because if a children’s story decides to be a little dark, a little unusual, a little unpredictable, a child’s brain will react. I suppose the Brothers Grimm figured this out a long time ago. I don’t believe I had any nightmares afterward, and I was certainly not terrified or traumatized – however very uneasy those early scenes in the clinic made me – but these decades later all I know is that I sought out the Oz books afterward, and started reading through them voraciously, which is not what you would call a negative reaction. I’m reading the Oz books again now, and doing so brought me back to this film which I hadn’t seen since I was nine. I was surprised at how vividly these scenes came back to me. This film was imprinted upon me. Disney should be more careful.

Although a sequel, with certain homages to the original film, Return to Oz is actually more closely aligned with L. Frank Baum’s source material. You have to realize that although The Wizard of Oz is cultural canon now, in the thirty-nine years before that movie’s release, Baum’s original books were the Harry Potter blockbuster events of the day. His 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was adapted into a hit stage play that toured the country and gained him a massive following among children. It took him four years to write a sequel, and he only did so because he was hoping another stage adaptation would be financially lucrative; but The Marvelous Land of Oz was a bigger hit as a book than a play, and he found himself press-ganged by kids into continuing an Oz series that he never really intended to keep going. His next, Ozma of Oz (1907), might be the best in the series, and he hoped it would be his last. But the fans would not be sated. He would go on to write another twelve, and after his death, other authors would keep fans returning to Oz on a regular basis, uncovering new lands and characters. The Victor Fleming/Judy Garland movie was just the latest iteration of the franchise’s multi-media success (there had already been comic strips and toys, and even a silent film). What’s odd is that the Oz momentum seemed to stop with that film’s release, and that it took almost forty years to produce a follow-up. Return to Oz adapts books two and three, conflating events and characters: a necessary move, perhaps, since Baum’s books are usually short on conflict. There are a few concessions to the original film – the slippers are ruby, not silver, for example – but it would be understandable if audiences of 1985, most of whom would not have read the books, were confused that there weren’t more connections…or musical numbers.

Although a sequel, with certain homages to the original film, Return to Oz is actually more closely aligned with L. Frank Baum’s source material. You have to realize that although The Wizard of Oz is cultural canon now, in the thirty-nine years before that movie’s release, Baum’s original books were the Harry Potter blockbuster events of the day. His 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was adapted into a hit stage play that toured the country and gained him a massive following among children. It took him four years to write a sequel, and he only did so because he was hoping another stage adaptation would be financially lucrative; but The Marvelous Land of Oz was a bigger hit as a book than a play, and he found himself press-ganged by kids into continuing an Oz series that he never really intended to keep going. His next, Ozma of Oz (1907), might be the best in the series, and he hoped it would be his last. But the fans would not be sated. He would go on to write another twelve, and after his death, other authors would keep fans returning to Oz on a regular basis, uncovering new lands and characters. The Victor Fleming/Judy Garland movie was just the latest iteration of the franchise’s multi-media success (there had already been comic strips and toys, and even a silent film). What’s odd is that the Oz momentum seemed to stop with that film’s release, and that it took almost forty years to produce a follow-up. Return to Oz adapts books two and three, conflating events and characters: a necessary move, perhaps, since Baum’s books are usually short on conflict. There are a few concessions to the original film – the slippers are ruby, not silver, for example – but it would be understandable if audiences of 1985, most of whom would not have read the books, were confused that there weren’t more connections…or musical numbers.

Dorothy Gale is played by a much younger actress than Judy Garland was: eleven-year-old Fairuza Balk. Introduced at Em and Henry’s farm, in long pigtails and with Toto sleeping beside her, this is all the introduction that an audience requires to be brought back up to speed. Since she keeps going on about this whole Oz business, her aunt (Piper Laurie) and uncle (Matt Clark) decide she should be taken to a doctor whose new therapeutic treatment is causing a buzz. Ha ha, get it? Because he’s going to send an electric current through her brain. The doctor, Worley (played by Nicol Williamson), demonstrates the machine by rolling it out into his hospital’s salon, weakly attempting to reassure Dorothy by showing how the machine has a face, with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, and a tongue that can move back and forth by a crank. That night, the nurse (Jean Marsh) straps Dorothy to a table and wheels her down the hallways toward that room where, shortly before, she’d heard screams issuing forth. Lightning is flashing out the window. Dorothy has metal earmuffs placed upon her head, like headphones. The doctor begins to crank his machine. At the sadistically last possible moment, the power shorts out, and Dorothy stages an escape with a young blonde girl (Emma Ridley). They eventually fall into a creek, and Dorothy grabs hold of some passing detritus as she drifts downstream. When she awakens, she’s inside a Kansas chicken coop with her favorite hen, Billina, beside her – but she’s surrounded by a desert, and Billina can now talk (with the voice of Mak Wilson). So this must be Oz.

Dorothy Gale is played by a much younger actress than Judy Garland was: eleven-year-old Fairuza Balk. Introduced at Em and Henry’s farm, in long pigtails and with Toto sleeping beside her, this is all the introduction that an audience requires to be brought back up to speed. Since she keeps going on about this whole Oz business, her aunt (Piper Laurie) and uncle (Matt Clark) decide she should be taken to a doctor whose new therapeutic treatment is causing a buzz. Ha ha, get it? Because he’s going to send an electric current through her brain. The doctor, Worley (played by Nicol Williamson), demonstrates the machine by rolling it out into his hospital’s salon, weakly attempting to reassure Dorothy by showing how the machine has a face, with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, and a tongue that can move back and forth by a crank. That night, the nurse (Jean Marsh) straps Dorothy to a table and wheels her down the hallways toward that room where, shortly before, she’d heard screams issuing forth. Lightning is flashing out the window. Dorothy has metal earmuffs placed upon her head, like headphones. The doctor begins to crank his machine. At the sadistically last possible moment, the power shorts out, and Dorothy stages an escape with a young blonde girl (Emma Ridley). They eventually fall into a creek, and Dorothy grabs hold of some passing detritus as she drifts downstream. When she awakens, she’s inside a Kansas chicken coop with her favorite hen, Billina, beside her – but she’s surrounded by a desert, and Billina can now talk (with the voice of Mak Wilson). So this must be Oz.

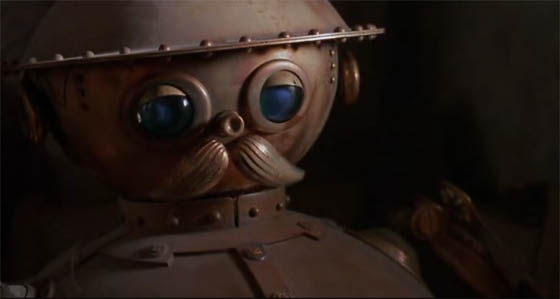

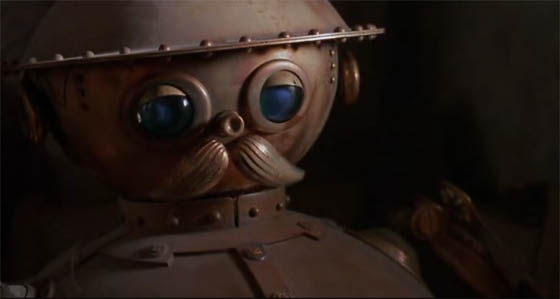

After escaping the Deadly Desert, Dorothy quickly discovers her old house, right where the tornado once dropped it. But the Yellow Brick Road has been torn up. When she follows it to the Emerald City, she finds that everyone has been turned to stone (and several citizens are missing their heads). Graffiti upon a wall warns, “Beware the Wheelers.” These creatures – actually just actors in clown makeup, bent on all fours and riding upon rollerblades, while wildly overacting – pursue Dorothy and Billina until they can take refuge in a secret room containing a rotund mechanical being: Tik-Tok. Representing the Royal Army of Oz, Tik-Tok can be operated by three cranks: one winds up his thoughts, another his speech, and the third his action. (Later, when his thoughts wind down but he keeps speaking, Billina complains that she’s never heard of such a thing, while Dorothy wisely claims that it happens to people all the time. This is vintage Baum.) Cobwebs swept away and cranks properly wound, Tik-Tok proves himself by whacking the Wheelers violently with Dorothy’s lunch-pail, then taking one hostage until he reveals that it’s the Nome King who has conquered the Emerald City. As in the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy begins enlisting some misfit friends to help restore the kingdom, including a makeshift animal magically constructed with the body of two sofas roped together, palm-leaf wings, a broom for a tail, and a “Gump” (Oz’s answer to a moose) for a head.

After escaping the Deadly Desert, Dorothy quickly discovers her old house, right where the tornado once dropped it. But the Yellow Brick Road has been torn up. When she follows it to the Emerald City, she finds that everyone has been turned to stone (and several citizens are missing their heads). Graffiti upon a wall warns, “Beware the Wheelers.” These creatures – actually just actors in clown makeup, bent on all fours and riding upon rollerblades, while wildly overacting – pursue Dorothy and Billina until they can take refuge in a secret room containing a rotund mechanical being: Tik-Tok. Representing the Royal Army of Oz, Tik-Tok can be operated by three cranks: one winds up his thoughts, another his speech, and the third his action. (Later, when his thoughts wind down but he keeps speaking, Billina complains that she’s never heard of such a thing, while Dorothy wisely claims that it happens to people all the time. This is vintage Baum.) Cobwebs swept away and cranks properly wound, Tik-Tok proves himself by whacking the Wheelers violently with Dorothy’s lunch-pail, then taking one hostage until he reveals that it’s the Nome King who has conquered the Emerald City. As in the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy begins enlisting some misfit friends to help restore the kingdom, including a makeshift animal magically constructed with the body of two sofas roped together, palm-leaf wings, a broom for a tail, and a “Gump” (Oz’s answer to a moose) for a head.

Tik-Tok is probably the most successfully transplanted character from the books, closely designed from John R. Neill’s original illustrations, and moving with a roly-poly, piston-y quality that is both natural-looking and immediately appealing. It helps, too, that Tik-Tok is pragmatic to a fault, and resolutely unemotional, no matter how dire the circumstance (though Disney can’t help but give him a scene late in the film where he sheds an oily tear, saps that they are). Equally impressive on a technical scale is Jack Pumpkinhead, tall and gawky, with a jack-o’-lantern grin that never moves. Most of the creations on display were courtesy of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Brian Henson voices Jack); and if you consider that the Nome King and his minions are the Claymation creations of Will Vinton Studios (of “California Raisins” fame, and the Claymation feature film The Adventures of Mark Twain), then what you have here is a strong sampling of pre-CG, 1980’s special effects, with all their limitations – and charm – on full display.

Tik-Tok is probably the most successfully transplanted character from the books, closely designed from John R. Neill’s original illustrations, and moving with a roly-poly, piston-y quality that is both natural-looking and immediately appealing. It helps, too, that Tik-Tok is pragmatic to a fault, and resolutely unemotional, no matter how dire the circumstance (though Disney can’t help but give him a scene late in the film where he sheds an oily tear, saps that they are). Equally impressive on a technical scale is Jack Pumpkinhead, tall and gawky, with a jack-o’-lantern grin that never moves. Most of the creations on display were courtesy of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Brian Henson voices Jack); and if you consider that the Nome King and his minions are the Claymation creations of Will Vinton Studios (of “California Raisins” fame, and the Claymation feature film The Adventures of Mark Twain), then what you have here is a strong sampling of pre-CG, 1980’s special effects, with all their limitations – and charm – on full display.

And this is a pretty ambitious effects film to attempt without the crutch of CG. It has a similar look to 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, another retro-fantasy, though Terry Gilliam is so adept in his use of miniatures that his film is more visually convincing. Honestly, I don’t even know why they attempted the Gump. The script requires the flying sofa to soar over the Deadly Desert, and then begin splitting apart; at one point Dorothy commands the Gump to dive so they can retrieve Jack’s decapitated head in mid-air. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of blue screen, all of it very iffy-looking. But when I saw this as a kid, I was enthralled by these action scenes, so certainly it worked for 1985. The Nome King begins as a fully-Claymation creature (first just a face in a rock wall), before transitioning, a bit awkwardly, into an actor (Nicol Williamson again) in full makeup. Most memorable in the film is Princess Mombi, who keeps a collection of young female heads in glass cabinets, swapping out her own on a whim. She captures Dorothy so that her head can someday join the collection. Director Walter Murch – a veteran film editor whose only directorial credit is this film – stages a chilling scene as Dorothy must sneak down that corridor of sleeping heads to steal Mombi’s magical elixir; when she opens the little cabinet at the end of the hall, she finds sitting right next to the potion the Mombi-head of actress Jean Marsh. The eyes open and she moans, “Dorothy Gaaaaale!” Pure horror movie stuff. (Though a modern viewer is likely to be reminded of Futurama and its jars of preserved celebrity heads.)

And this is a pretty ambitious effects film to attempt without the crutch of CG. It has a similar look to 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, another retro-fantasy, though Terry Gilliam is so adept in his use of miniatures that his film is more visually convincing. Honestly, I don’t even know why they attempted the Gump. The script requires the flying sofa to soar over the Deadly Desert, and then begin splitting apart; at one point Dorothy commands the Gump to dive so they can retrieve Jack’s decapitated head in mid-air. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of blue screen, all of it very iffy-looking. But when I saw this as a kid, I was enthralled by these action scenes, so certainly it worked for 1985. The Nome King begins as a fully-Claymation creature (first just a face in a rock wall), before transitioning, a bit awkwardly, into an actor (Nicol Williamson again) in full makeup. Most memorable in the film is Princess Mombi, who keeps a collection of young female heads in glass cabinets, swapping out her own on a whim. She captures Dorothy so that her head can someday join the collection. Director Walter Murch – a veteran film editor whose only directorial credit is this film – stages a chilling scene as Dorothy must sneak down that corridor of sleeping heads to steal Mombi’s magical elixir; when she opens the little cabinet at the end of the hall, she finds sitting right next to the potion the Mombi-head of actress Jean Marsh. The eyes open and she moans, “Dorothy Gaaaaale!” Pure horror movie stuff. (Though a modern viewer is likely to be reminded of Futurama and its jars of preserved celebrity heads.)

The princess who wants Dorothy’s head for her own is straight out of Ozma of Oz, though in the book she’s a princess of the kingdom of Ev, not Oz. “Mombi” is the name of a witch who possesses a life-giving magical potion, which creates Jack Pumpkinhead – so you can see how the movie is faithful without being slavish. There are actually a number of touches to satisfy fans of the books, but just the art direction and costume design is enough to put a smile on the face of every Oz-ite. Renowned comic book artist Mike Ploog (Abadazad) served as illustrator and storyboard artist; along with supervising art director Charles Bishop (Young Sherlock Holmes) and art director Fred Hole (Avalon; Star Wars: Episodes I & II), the team worked to ensure that the turn-of-the-century illustrations by John R. Neill are taken as Bible. (Incidentally, a close inspection of the credits reveals that Henry Selick, later to direct The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, also did storyboard work.) Just look at the Emerald City, particularly in the finale: it looks like a scene from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair – which makes sense. Baum attended and was influenced by the Fair when he wrote the first Oz book. The cast that gathers around Scarecrow’s throne all faithfully adhere to Neill’s art, the aesthetic alternating between toy-soldier and Art Nouveau (Maxfield Parrish is clearly an influence here as well). Blink and you’ll miss cameos from other Oz characters: Santa Claus (from The Road to Oz) and – I think – the Shaggy Man and the Captain General. The Scarecrow, The Tin Man, and The Cowardly Lion are modeled after the books, not the Fleming film, and as a further gesture to fans, the Cowardly Lion even has a bow at the top of his head. Ozma (Emma Ridley once more) is her own illustration incarnate. This is a beautiful-looking film.

The princess who wants Dorothy’s head for her own is straight out of Ozma of Oz, though in the book she’s a princess of the kingdom of Ev, not Oz. “Mombi” is the name of a witch who possesses a life-giving magical potion, which creates Jack Pumpkinhead – so you can see how the movie is faithful without being slavish. There are actually a number of touches to satisfy fans of the books, but just the art direction and costume design is enough to put a smile on the face of every Oz-ite. Renowned comic book artist Mike Ploog (Abadazad) served as illustrator and storyboard artist; along with supervising art director Charles Bishop (Young Sherlock Holmes) and art director Fred Hole (Avalon; Star Wars: Episodes I & II), the team worked to ensure that the turn-of-the-century illustrations by John R. Neill are taken as Bible. (Incidentally, a close inspection of the credits reveals that Henry Selick, later to direct The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, also did storyboard work.) Just look at the Emerald City, particularly in the finale: it looks like a scene from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair – which makes sense. Baum attended and was influenced by the Fair when he wrote the first Oz book. The cast that gathers around Scarecrow’s throne all faithfully adhere to Neill’s art, the aesthetic alternating between toy-soldier and Art Nouveau (Maxfield Parrish is clearly an influence here as well). Blink and you’ll miss cameos from other Oz characters: Santa Claus (from The Road to Oz) and – I think – the Shaggy Man and the Captain General. The Scarecrow, The Tin Man, and The Cowardly Lion are modeled after the books, not the Fleming film, and as a further gesture to fans, the Cowardly Lion even has a bow at the top of his head. Ozma (Emma Ridley once more) is her own illustration incarnate. This is a beautiful-looking film.

Is it a perfect film? Not by a Yellow Brick mile. The Wheelers are distracting and look cheap compared to the effort that’s gone into the designs of the rest of the characters. There’s also something intangible but essential missing. Perhaps the filmmakers were so intent on creating a darker Oz film that they lost touch with the enchantment, the feeling of magic, that any Oz excursion requires. However memorable the opening sequences are, they seem misguided to a baffling extent. Why is it necessary for Dorothy to go through this? Why would Uncle Henry and Aunt Em ever subject their child to torture to cure her of imaginary friends? What is the film trying to say?

Is it a perfect film? Not by a Yellow Brick mile. The Wheelers are distracting and look cheap compared to the effort that’s gone into the designs of the rest of the characters. There’s also something intangible but essential missing. Perhaps the filmmakers were so intent on creating a darker Oz film that they lost touch with the enchantment, the feeling of magic, that any Oz excursion requires. However memorable the opening sequences are, they seem misguided to a baffling extent. Why is it necessary for Dorothy to go through this? Why would Uncle Henry and Aunt Em ever subject their child to torture to cure her of imaginary friends? What is the film trying to say?

In the final scene, Ozma appears in Dorothy’s mirror, but when Dorothy tries to summon her parents to look, Ozma places a finger on her lips. Sssh. Don’t let the grown-ups know that you have an imagination! Maybe they’ll try lobotomy next, Dorothy – watch out. Further, it’s practically underlined that Dorothy didn’t really go to Oz. In Ozma of Oz, she visits by falling overboard on a sea voyage to Australia, and drifts in the coop until she arrives at the kingdom of Ev. But it’s made explicit in the film that she’s only been dreaming; in its closest homage to the original film, actors who appear in Kansas recur in Oz as doppelgangers (the “double” theme is echoed by Ozma’s arrival through a mirror, replacing Dorothy’s own reflection). I always bristle when fantasy has to be placed in a realistic “context” to make it palatable for skeptical viewers. It’s patronizing toward the children in the audience, for one thing, but it also betrays the childlike logic which abounds in Baum’s original novels. Baum tells the children that they’re wise, brave, and know things adults don’t know about. In 1910’s The Emerald City of Oz, Dorothy has to reassure her aunt and uncle that yes, there is an Oz – and in a remarkable scene, she saves them from their anxieties about debt and home foreclosure (!) by using Ozma’s magic to draw them into Oz so they can not only see for themselves, but spend the rest of their lives without the worries of the boring, drab, “real” world. Maybe this is why there are so many Oz films currently in development; with fears of a “double-dip recession” in the news, what we really need right now is to open up package tours to Oz. Sign me up.

In the final scene, Ozma appears in Dorothy’s mirror, but when Dorothy tries to summon her parents to look, Ozma places a finger on her lips. Sssh. Don’t let the grown-ups know that you have an imagination! Maybe they’ll try lobotomy next, Dorothy – watch out. Further, it’s practically underlined that Dorothy didn’t really go to Oz. In Ozma of Oz, she visits by falling overboard on a sea voyage to Australia, and drifts in the coop until she arrives at the kingdom of Ev. But it’s made explicit in the film that she’s only been dreaming; in its closest homage to the original film, actors who appear in Kansas recur in Oz as doppelgangers (the “double” theme is echoed by Ozma’s arrival through a mirror, replacing Dorothy’s own reflection). I always bristle when fantasy has to be placed in a realistic “context” to make it palatable for skeptical viewers. It’s patronizing toward the children in the audience, for one thing, but it also betrays the childlike logic which abounds in Baum’s original novels. Baum tells the children that they’re wise, brave, and know things adults don’t know about. In 1910’s The Emerald City of Oz, Dorothy has to reassure her aunt and uncle that yes, there is an Oz – and in a remarkable scene, she saves them from their anxieties about debt and home foreclosure (!) by using Ozma’s magic to draw them into Oz so they can not only see for themselves, but spend the rest of their lives without the worries of the boring, drab, “real” world. Maybe this is why there are so many Oz films currently in development; with fears of a “double-dip recession” in the news, what we really need right now is to open up package tours to Oz. Sign me up.

In our journey through the cinema of William Castle, we are now, perhaps, reaching the point where our horror producer/director/showman extraordinaire might wish to consider giving up that whole “gimmick” thing which had been his cash-cow up until now. Because Mr. Sardonicus (1961) is an interesting film. I’d say that it doesn’t need a gimmick, upon which his previous films had relied so heavily. But the real problem here is that the gimmick is not integrated organically, as it was in The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960). Instead, like the same year’s Homicidal (1961), it springs at our faces like a jack-in-the-box at a point in the film that we’ve become lost in the story, and don’t want to be reminded that it’s “just a movie” – just another William Castle put-on. Mr. Sardonicus, before it goes off the rails, has promise.

In our journey through the cinema of William Castle, we are now, perhaps, reaching the point where our horror producer/director/showman extraordinaire might wish to consider giving up that whole “gimmick” thing which had been his cash-cow up until now. Because Mr. Sardonicus (1961) is an interesting film. I’d say that it doesn’t need a gimmick, upon which his previous films had relied so heavily. But the real problem here is that the gimmick is not integrated organically, as it was in The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960). Instead, like the same year’s Homicidal (1961), it springs at our faces like a jack-in-the-box at a point in the film that we’ve become lost in the story, and don’t want to be reminded that it’s “just a movie” – just another William Castle put-on. Mr. Sardonicus, before it goes off the rails, has promise. Ray Russell adapted his own short story, “Sardonicus,” which had just been published in Playboy. The difference between the film and its source largely comes down to padding: it probably wouldn’t take 90 minutes to read “Sardonicus,” so Russell largely adds scenes of torture and sadism, presumably at Castle’s request, along with some repetitive dialogue and slow reveals of information that the audience had probably figured out much earlier. In other words, it could be shorter, and the source material is better, but couldn’t you say that about most films? Ronald Lewis (Scream of Fear) plays a young doctor, Robert Cargrave, whose work on patients suffering from various versions of paralysis has led to modest fame and a knighthood. As soon as he receives a written invitation from his former – and unrequited – flame (Audrey Dalton of 1953’s Titanic), now going by the title of Baroness Maude Sardonicus, he drops everything and heads to the dark and sinister castle where she now lives with her mysterious husband, the Baron (Guy Rolfe of Yesterday’s Enemy). How mysterious is the Baron? So mysterious he wears a lifelike mask to hide his features: a mask that slightly resembles William Castle, oddly enough.

Ray Russell adapted his own short story, “Sardonicus,” which had just been published in Playboy. The difference between the film and its source largely comes down to padding: it probably wouldn’t take 90 minutes to read “Sardonicus,” so Russell largely adds scenes of torture and sadism, presumably at Castle’s request, along with some repetitive dialogue and slow reveals of information that the audience had probably figured out much earlier. In other words, it could be shorter, and the source material is better, but couldn’t you say that about most films? Ronald Lewis (Scream of Fear) plays a young doctor, Robert Cargrave, whose work on patients suffering from various versions of paralysis has led to modest fame and a knighthood. As soon as he receives a written invitation from his former – and unrequited – flame (Audrey Dalton of 1953’s Titanic), now going by the title of Baroness Maude Sardonicus, he drops everything and heads to the dark and sinister castle where she now lives with her mysterious husband, the Baron (Guy Rolfe of Yesterday’s Enemy). How mysterious is the Baron? So mysterious he wears a lifelike mask to hide his features: a mask that slightly resembles William Castle, oddly enough. Sir Robert knows something strange is up as soon as he enters the castle: following a woman’s screams, and ignoring the protestations of the one-eyed servant, he discovers that the maid has been tied up and covered in leeches. After liberating the maid, and receiving some assurances from the Bela Lugosi-esque servant, Krull (Oskar Homolka), that her wounds will be cared for, he shortly meets his beloved, as well as her tyrannical husband, so desperate to seek treatment for his hidden ailment that he resorts to routinely experimenting upon his staff. Sir Robert at last persuades Sardonicus to remove his mask, revealing a face pulled into a ghastly rictus grin (a la The Man Who Laughs; or Batman‘s Joker). Sardonicus tells his tale of woe: many years ago, his father died, but it was discovered only after he was buried that he took a winning lottery ticket with him. It was Sardonicus who elected to dig up his father’s corpse to recover the ticket on his person, but he was so struck with horror at the man’s partially-decomposed face, the mouth a rigor-mortis grin, that his own features were altered in a kind of psychosomatic reaction – mirroring the death-smile of the corpse. Now Sardonicus needs Sir Robert to accomplish what no other physician has been able to do: restore his face to its former handsomeness.

Sir Robert knows something strange is up as soon as he enters the castle: following a woman’s screams, and ignoring the protestations of the one-eyed servant, he discovers that the maid has been tied up and covered in leeches. After liberating the maid, and receiving some assurances from the Bela Lugosi-esque servant, Krull (Oskar Homolka), that her wounds will be cared for, he shortly meets his beloved, as well as her tyrannical husband, so desperate to seek treatment for his hidden ailment that he resorts to routinely experimenting upon his staff. Sir Robert at last persuades Sardonicus to remove his mask, revealing a face pulled into a ghastly rictus grin (a la The Man Who Laughs; or Batman‘s Joker). Sardonicus tells his tale of woe: many years ago, his father died, but it was discovered only after he was buried that he took a winning lottery ticket with him. It was Sardonicus who elected to dig up his father’s corpse to recover the ticket on his person, but he was so struck with horror at the man’s partially-decomposed face, the mouth a rigor-mortis grin, that his own features were altered in a kind of psychosomatic reaction – mirroring the death-smile of the corpse. Now Sardonicus needs Sir Robert to accomplish what no other physician has been able to do: restore his face to its former handsomeness. Sir Robert takes sympathy at first (apparently forgetting all about the maid with the leeches), and agrees to begin treatment immediately, but very soon finds that the facial muscles of Sardonicus are too rigid to manipulate. Yet Baron Sardonicus will not accept “no, you crazed sadist” for an answer. He threatens to torture and rape Maude, who had up until now been “wife” in name only – so Robert complies with the only treatment that could possibly work on someone as psychologically disturbed as Sardonicus. Again, this is all faithful to Russell’s story, but expanded; the most significant change is that Sardonicus wears a mask to hide his appearance, and has taught himself to ventriloquize past his clamped teeth and parted lips, so he can annunciate his m‘s and b‘s, and speak with Guy Rolfe’s impeccable diction.

Sir Robert takes sympathy at first (apparently forgetting all about the maid with the leeches), and agrees to begin treatment immediately, but very soon finds that the facial muscles of Sardonicus are too rigid to manipulate. Yet Baron Sardonicus will not accept “no, you crazed sadist” for an answer. He threatens to torture and rape Maude, who had up until now been “wife” in name only – so Robert complies with the only treatment that could possibly work on someone as psychologically disturbed as Sardonicus. Again, this is all faithful to Russell’s story, but expanded; the most significant change is that Sardonicus wears a mask to hide his appearance, and has taught himself to ventriloquize past his clamped teeth and parted lips, so he can annunciate his m‘s and b‘s, and speak with Guy Rolfe’s impeccable diction. William Castle’s idea of period (19th century) horror seems rooted in 30’s and 40’s Universal Studios monster movies. Fog permeates every outdoor set, conveniently hiding the studio’s limitations, and the castle interiors are crawling with Expressionistic shadows. (The most Expressionistic touch is Sardonicus’s castle, which resembles a grinning skull.) Accents vary wildly in quality, but Ronald Lewis is quite good in the central role, and Rolfe, presumably cast because of his Basil Rathbone qualities, creates a chilling personality that the mask can’t hide. Despite the fact that he casually tortures his maid (she’s strung up by her thumbs at one point), his creepiest moment comes when he surveys a group of village girls that Krull has gathered. The girls thought they were being offered money to attend a party; instead, Sardonicus is seeking a sexual partner in the absence of his wife’s affections. He looks them over like slaves on an auction block. You wouldn’t see this in a Karloff/Lugosi film.

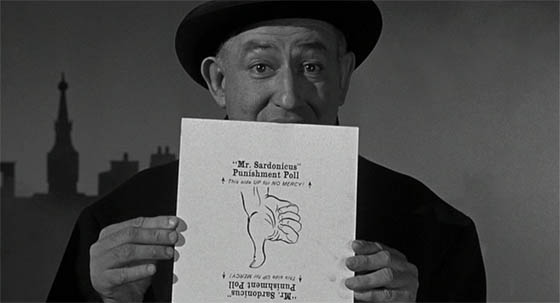

William Castle’s idea of period (19th century) horror seems rooted in 30’s and 40’s Universal Studios monster movies. Fog permeates every outdoor set, conveniently hiding the studio’s limitations, and the castle interiors are crawling with Expressionistic shadows. (The most Expressionistic touch is Sardonicus’s castle, which resembles a grinning skull.) Accents vary wildly in quality, but Ronald Lewis is quite good in the central role, and Rolfe, presumably cast because of his Basil Rathbone qualities, creates a chilling personality that the mask can’t hide. Despite the fact that he casually tortures his maid (she’s strung up by her thumbs at one point), his creepiest moment comes when he surveys a group of village girls that Krull has gathered. The girls thought they were being offered money to attend a party; instead, Sardonicus is seeking a sexual partner in the absence of his wife’s affections. He looks them over like slaves on an auction block. You wouldn’t see this in a Karloff/Lugosi film. All these edgy, “modern” horror touches – sex and sadism – serve Castle only to a point, because he cannot resist, two minutes from the end of the picture, interrupting the story to address us directly. It’s time for the “Punishment Poll.” Each audience member was handed a small sign depicting a hand aiming a thumb. Castle asks the crowd to hold their cards out facing the screen – so he can read them – and give a thumb’s-up if Sardonicus doesn’t deserve punishment, or a thumb’s-down if he should “suffer, suffer, suffer.” Castle leans toward the camera, squinting, and pretends to take count of all thumbs in the audience. The conclusion to this exercise shouldn’t surprise you. The audience has voted to punish Sardonicus – I mean, come on, leeches on maids! – and so we witness the Baron’s come-uppance. There was never a happy ending filmed for Mr. Sardonicus, and of course the audience knew what the poll result would inevitably be. They were playing along. Castle always promised a good time, and audiences expected this sort of thing by now. But the adult and disturbing tone of what played in the last eighty or so minutes does not call for Castle’s final cameo, and another audience-participation game. With Homicidal, he had begun to make his films more adult. Mr. Sardonicus suggests that perhaps it was time to leave those kids at home.

All these edgy, “modern” horror touches – sex and sadism – serve Castle only to a point, because he cannot resist, two minutes from the end of the picture, interrupting the story to address us directly. It’s time for the “Punishment Poll.” Each audience member was handed a small sign depicting a hand aiming a thumb. Castle asks the crowd to hold their cards out facing the screen – so he can read them – and give a thumb’s-up if Sardonicus doesn’t deserve punishment, or a thumb’s-down if he should “suffer, suffer, suffer.” Castle leans toward the camera, squinting, and pretends to take count of all thumbs in the audience. The conclusion to this exercise shouldn’t surprise you. The audience has voted to punish Sardonicus – I mean, come on, leeches on maids! – and so we witness the Baron’s come-uppance. There was never a happy ending filmed for Mr. Sardonicus, and of course the audience knew what the poll result would inevitably be. They were playing along. Castle always promised a good time, and audiences expected this sort of thing by now. But the adult and disturbing tone of what played in the last eighty or so minutes does not call for Castle’s final cameo, and another audience-participation game. With Homicidal, he had begun to make his films more adult. Mr. Sardonicus suggests that perhaps it was time to leave those kids at home.

In the years prior to The Little Mermaid (1989), Disney was adrift, not sure exactly what kind of movie it should be making. In the same year that the studio produced a dark but unfocused animated fantasy (The Black Cauldron), they released Return to Oz (1985), a live-action sequel to The Wizard of Oz (1939) which would open with Dorothy being delivered by Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to a quack doctor for electroshock therapy treatment in hopes of “curing” the girl of those Oz fantasies she holds so dear. Yes, Disney thought this was a great idea for a big budget children’s movie. But kids are more mature than they seem, right? Listen – ask anyone of my generation what they remember about Return to Oz and you will get the same answer: “Oh! God! Electroshock therapy!” Walt Disney Studios apparently wanted into the nightmare business.

In the years prior to The Little Mermaid (1989), Disney was adrift, not sure exactly what kind of movie it should be making. In the same year that the studio produced a dark but unfocused animated fantasy (The Black Cauldron), they released Return to Oz (1985), a live-action sequel to The Wizard of Oz (1939) which would open with Dorothy being delivered by Uncle Henry and Aunt Em to a quack doctor for electroshock therapy treatment in hopes of “curing” the girl of those Oz fantasies she holds so dear. Yes, Disney thought this was a great idea for a big budget children’s movie. But kids are more mature than they seem, right? Listen – ask anyone of my generation what they remember about Return to Oz and you will get the same answer: “Oh! God! Electroshock therapy!” Walt Disney Studios apparently wanted into the nightmare business. I saw this film in the theater when I was nine years old. All I knew of Oz was the original film, which we watched, like every family’s ritual, once a year. Return to Oz transfixed me for its entire two-hour running time. I paid absolute attention. Because if a children’s story decides to be a little dark, a little unusual, a little unpredictable, a child’s brain will react. I suppose the Brothers Grimm figured this out a long time ago. I don’t believe I had any nightmares afterward, and I was certainly not terrified or traumatized – however very uneasy those early scenes in the clinic made me – but these decades later all I know is that I sought out the Oz books afterward, and started reading through them voraciously, which is not what you would call a negative reaction. I’m reading the Oz books again now, and doing so brought me back to this film which I hadn’t seen since I was nine. I was surprised at how vividly these scenes came back to me. This film was imprinted upon me. Disney should be more careful.

I saw this film in the theater when I was nine years old. All I knew of Oz was the original film, which we watched, like every family’s ritual, once a year. Return to Oz transfixed me for its entire two-hour running time. I paid absolute attention. Because if a children’s story decides to be a little dark, a little unusual, a little unpredictable, a child’s brain will react. I suppose the Brothers Grimm figured this out a long time ago. I don’t believe I had any nightmares afterward, and I was certainly not terrified or traumatized – however very uneasy those early scenes in the clinic made me – but these decades later all I know is that I sought out the Oz books afterward, and started reading through them voraciously, which is not what you would call a negative reaction. I’m reading the Oz books again now, and doing so brought me back to this film which I hadn’t seen since I was nine. I was surprised at how vividly these scenes came back to me. This film was imprinted upon me. Disney should be more careful. Although a sequel, with certain homages to the original film, Return to Oz is actually more closely aligned with L. Frank Baum’s source material. You have to realize that although The Wizard of Oz is cultural canon now, in the thirty-nine years before that movie’s release, Baum’s original books were the Harry Potter blockbuster events of the day. His 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was adapted into a hit stage play that toured the country and gained him a massive following among children. It took him four years to write a sequel, and he only did so because he was hoping another stage adaptation would be financially lucrative; but The Marvelous Land of Oz was a bigger hit as a book than a play, and he found himself press-ganged by kids into continuing an Oz series that he never really intended to keep going. His next, Ozma of Oz (1907), might be the best in the series, and he hoped it would be his last. But the fans would not be sated. He would go on to write another twelve, and after his death, other authors would keep fans returning to Oz on a regular basis, uncovering new lands and characters. The Victor Fleming/Judy Garland movie was just the latest iteration of the franchise’s multi-media success (there had already been comic strips and toys, and even a silent film). What’s odd is that the Oz momentum seemed to stop with that film’s release, and that it took almost forty years to produce a follow-up. Return to Oz adapts books two and three, conflating events and characters: a necessary move, perhaps, since Baum’s books are usually short on conflict. There are a few concessions to the original film – the slippers are ruby, not silver, for example – but it would be understandable if audiences of 1985, most of whom would not have read the books, were confused that there weren’t more connections…or musical numbers.

Although a sequel, with certain homages to the original film, Return to Oz is actually more closely aligned with L. Frank Baum’s source material. You have to realize that although The Wizard of Oz is cultural canon now, in the thirty-nine years before that movie’s release, Baum’s original books were the Harry Potter blockbuster events of the day. His 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was adapted into a hit stage play that toured the country and gained him a massive following among children. It took him four years to write a sequel, and he only did so because he was hoping another stage adaptation would be financially lucrative; but The Marvelous Land of Oz was a bigger hit as a book than a play, and he found himself press-ganged by kids into continuing an Oz series that he never really intended to keep going. His next, Ozma of Oz (1907), might be the best in the series, and he hoped it would be his last. But the fans would not be sated. He would go on to write another twelve, and after his death, other authors would keep fans returning to Oz on a regular basis, uncovering new lands and characters. The Victor Fleming/Judy Garland movie was just the latest iteration of the franchise’s multi-media success (there had already been comic strips and toys, and even a silent film). What’s odd is that the Oz momentum seemed to stop with that film’s release, and that it took almost forty years to produce a follow-up. Return to Oz adapts books two and three, conflating events and characters: a necessary move, perhaps, since Baum’s books are usually short on conflict. There are a few concessions to the original film – the slippers are ruby, not silver, for example – but it would be understandable if audiences of 1985, most of whom would not have read the books, were confused that there weren’t more connections…or musical numbers. Dorothy Gale is played by a much younger actress than Judy Garland was: eleven-year-old Fairuza Balk. Introduced at Em and Henry’s farm, in long pigtails and with Toto sleeping beside her, this is all the introduction that an audience requires to be brought back up to speed. Since she keeps going on about this whole Oz business, her aunt (Piper Laurie) and uncle (Matt Clark) decide she should be taken to a doctor whose new therapeutic treatment is causing a buzz. Ha ha, get it? Because he’s going to send an electric current through her brain. The doctor, Worley (played by Nicol Williamson), demonstrates the machine by rolling it out into his hospital’s salon, weakly attempting to reassure Dorothy by showing how the machine has a face, with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, and a tongue that can move back and forth by a crank. That night, the nurse (Jean Marsh) straps Dorothy to a table and wheels her down the hallways toward that room where, shortly before, she’d heard screams issuing forth. Lightning is flashing out the window. Dorothy has metal earmuffs placed upon her head, like headphones. The doctor begins to crank his machine. At the sadistically last possible moment, the power shorts out, and Dorothy stages an escape with a young blonde girl (Emma Ridley). They eventually fall into a creek, and Dorothy grabs hold of some passing detritus as she drifts downstream. When she awakens, she’s inside a Kansas chicken coop with her favorite hen, Billina, beside her – but she’s surrounded by a desert, and Billina can now talk (with the voice of Mak Wilson). So this must be Oz.

Dorothy Gale is played by a much younger actress than Judy Garland was: eleven-year-old Fairuza Balk. Introduced at Em and Henry’s farm, in long pigtails and with Toto sleeping beside her, this is all the introduction that an audience requires to be brought back up to speed. Since she keeps going on about this whole Oz business, her aunt (Piper Laurie) and uncle (Matt Clark) decide she should be taken to a doctor whose new therapeutic treatment is causing a buzz. Ha ha, get it? Because he’s going to send an electric current through her brain. The doctor, Worley (played by Nicol Williamson), demonstrates the machine by rolling it out into his hospital’s salon, weakly attempting to reassure Dorothy by showing how the machine has a face, with two eyes, a nose, a mouth, and a tongue that can move back and forth by a crank. That night, the nurse (Jean Marsh) straps Dorothy to a table and wheels her down the hallways toward that room where, shortly before, she’d heard screams issuing forth. Lightning is flashing out the window. Dorothy has metal earmuffs placed upon her head, like headphones. The doctor begins to crank his machine. At the sadistically last possible moment, the power shorts out, and Dorothy stages an escape with a young blonde girl (Emma Ridley). They eventually fall into a creek, and Dorothy grabs hold of some passing detritus as she drifts downstream. When she awakens, she’s inside a Kansas chicken coop with her favorite hen, Billina, beside her – but she’s surrounded by a desert, and Billina can now talk (with the voice of Mak Wilson). So this must be Oz. After escaping the Deadly Desert, Dorothy quickly discovers her old house, right where the tornado once dropped it. But the Yellow Brick Road has been torn up. When she follows it to the Emerald City, she finds that everyone has been turned to stone (and several citizens are missing their heads). Graffiti upon a wall warns, “Beware the Wheelers.” These creatures – actually just actors in clown makeup, bent on all fours and riding upon rollerblades, while wildly overacting – pursue Dorothy and Billina until they can take refuge in a secret room containing a rotund mechanical being: Tik-Tok. Representing the Royal Army of Oz, Tik-Tok can be operated by three cranks: one winds up his thoughts, another his speech, and the third his action. (Later, when his thoughts wind down but he keeps speaking, Billina complains that she’s never heard of such a thing, while Dorothy wisely claims that it happens to people all the time. This is vintage Baum.) Cobwebs swept away and cranks properly wound, Tik-Tok proves himself by whacking the Wheelers violently with Dorothy’s lunch-pail, then taking one hostage until he reveals that it’s the Nome King who has conquered the Emerald City. As in the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy begins enlisting some misfit friends to help restore the kingdom, including a makeshift animal magically constructed with the body of two sofas roped together, palm-leaf wings, a broom for a tail, and a “Gump” (Oz’s answer to a moose) for a head.

After escaping the Deadly Desert, Dorothy quickly discovers her old house, right where the tornado once dropped it. But the Yellow Brick Road has been torn up. When she follows it to the Emerald City, she finds that everyone has been turned to stone (and several citizens are missing their heads). Graffiti upon a wall warns, “Beware the Wheelers.” These creatures – actually just actors in clown makeup, bent on all fours and riding upon rollerblades, while wildly overacting – pursue Dorothy and Billina until they can take refuge in a secret room containing a rotund mechanical being: Tik-Tok. Representing the Royal Army of Oz, Tik-Tok can be operated by three cranks: one winds up his thoughts, another his speech, and the third his action. (Later, when his thoughts wind down but he keeps speaking, Billina complains that she’s never heard of such a thing, while Dorothy wisely claims that it happens to people all the time. This is vintage Baum.) Cobwebs swept away and cranks properly wound, Tik-Tok proves himself by whacking the Wheelers violently with Dorothy’s lunch-pail, then taking one hostage until he reveals that it’s the Nome King who has conquered the Emerald City. As in the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy begins enlisting some misfit friends to help restore the kingdom, including a makeshift animal magically constructed with the body of two sofas roped together, palm-leaf wings, a broom for a tail, and a “Gump” (Oz’s answer to a moose) for a head. Tik-Tok is probably the most successfully transplanted character from the books, closely designed from John R. Neill’s original illustrations, and moving with a roly-poly, piston-y quality that is both natural-looking and immediately appealing. It helps, too, that Tik-Tok is pragmatic to a fault, and resolutely unemotional, no matter how dire the circumstance (though Disney can’t help but give him a scene late in the film where he sheds an oily tear, saps that they are). Equally impressive on a technical scale is Jack Pumpkinhead, tall and gawky, with a jack-o’-lantern grin that never moves. Most of the creations on display were courtesy of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Brian Henson voices Jack); and if you consider that the Nome King and his minions are the Claymation creations of Will Vinton Studios (of “California Raisins” fame, and the Claymation feature film The Adventures of Mark Twain), then what you have here is a strong sampling of pre-CG, 1980’s special effects, with all their limitations – and charm – on full display.

Tik-Tok is probably the most successfully transplanted character from the books, closely designed from John R. Neill’s original illustrations, and moving with a roly-poly, piston-y quality that is both natural-looking and immediately appealing. It helps, too, that Tik-Tok is pragmatic to a fault, and resolutely unemotional, no matter how dire the circumstance (though Disney can’t help but give him a scene late in the film where he sheds an oily tear, saps that they are). Equally impressive on a technical scale is Jack Pumpkinhead, tall and gawky, with a jack-o’-lantern grin that never moves. Most of the creations on display were courtesy of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Brian Henson voices Jack); and if you consider that the Nome King and his minions are the Claymation creations of Will Vinton Studios (of “California Raisins” fame, and the Claymation feature film The Adventures of Mark Twain), then what you have here is a strong sampling of pre-CG, 1980’s special effects, with all their limitations – and charm – on full display. And this is a pretty ambitious effects film to attempt without the crutch of CG. It has a similar look to 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, another retro-fantasy, though Terry Gilliam is so adept in his use of miniatures that his film is more visually convincing. Honestly, I don’t even know why they attempted the Gump. The script requires the flying sofa to soar over the Deadly Desert, and then begin splitting apart; at one point Dorothy commands the Gump to dive so they can retrieve Jack’s decapitated head in mid-air. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of blue screen, all of it very iffy-looking. But when I saw this as a kid, I was enthralled by these action scenes, so certainly it worked for 1985. The Nome King begins as a fully-Claymation creature (first just a face in a rock wall), before transitioning, a bit awkwardly, into an actor (Nicol Williamson again) in full makeup. Most memorable in the film is Princess Mombi, who keeps a collection of young female heads in glass cabinets, swapping out her own on a whim. She captures Dorothy so that her head can someday join the collection. Director Walter Murch – a veteran film editor whose only directorial credit is this film – stages a chilling scene as Dorothy must sneak down that corridor of sleeping heads to steal Mombi’s magical elixir; when she opens the little cabinet at the end of the hall, she finds sitting right next to the potion the Mombi-head of actress Jean Marsh. The eyes open and she moans, “Dorothy Gaaaaale!” Pure horror movie stuff. (Though a modern viewer is likely to be reminded of Futurama and its jars of preserved celebrity heads.)

And this is a pretty ambitious effects film to attempt without the crutch of CG. It has a similar look to 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, another retro-fantasy, though Terry Gilliam is so adept in his use of miniatures that his film is more visually convincing. Honestly, I don’t even know why they attempted the Gump. The script requires the flying sofa to soar over the Deadly Desert, and then begin splitting apart; at one point Dorothy commands the Gump to dive so they can retrieve Jack’s decapitated head in mid-air. Suffice it to say, there’s a lot of blue screen, all of it very iffy-looking. But when I saw this as a kid, I was enthralled by these action scenes, so certainly it worked for 1985. The Nome King begins as a fully-Claymation creature (first just a face in a rock wall), before transitioning, a bit awkwardly, into an actor (Nicol Williamson again) in full makeup. Most memorable in the film is Princess Mombi, who keeps a collection of young female heads in glass cabinets, swapping out her own on a whim. She captures Dorothy so that her head can someday join the collection. Director Walter Murch – a veteran film editor whose only directorial credit is this film – stages a chilling scene as Dorothy must sneak down that corridor of sleeping heads to steal Mombi’s magical elixir; when she opens the little cabinet at the end of the hall, she finds sitting right next to the potion the Mombi-head of actress Jean Marsh. The eyes open and she moans, “Dorothy Gaaaaale!” Pure horror movie stuff. (Though a modern viewer is likely to be reminded of Futurama and its jars of preserved celebrity heads.) The princess who wants Dorothy’s head for her own is straight out of Ozma of Oz, though in the book she’s a princess of the kingdom of Ev, not Oz. “Mombi” is the name of a witch who possesses a life-giving magical potion, which creates Jack Pumpkinhead – so you can see how the movie is faithful without being slavish. There are actually a number of touches to satisfy fans of the books, but just the art direction and costume design is enough to put a smile on the face of every Oz-ite. Renowned comic book artist Mike Ploog (Abadazad) served as illustrator and storyboard artist; along with supervising art director Charles Bishop (Young Sherlock Holmes) and art director Fred Hole (Avalon; Star Wars: Episodes I & II), the team worked to ensure that the turn-of-the-century illustrations by John R. Neill are taken as Bible. (Incidentally, a close inspection of the credits reveals that Henry Selick, later to direct The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, also did storyboard work.) Just look at the Emerald City, particularly in the finale: it looks like a scene from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair – which makes sense. Baum attended and was influenced by the Fair when he wrote the first Oz book. The cast that gathers around Scarecrow’s throne all faithfully adhere to Neill’s art, the aesthetic alternating between toy-soldier and Art Nouveau (Maxfield Parrish is clearly an influence here as well). Blink and you’ll miss cameos from other Oz characters: Santa Claus (from The Road to Oz) and – I think – the Shaggy Man and the Captain General. The Scarecrow, The Tin Man, and The Cowardly Lion are modeled after the books, not the Fleming film, and as a further gesture to fans, the Cowardly Lion even has a bow at the top of his head. Ozma (Emma Ridley once more) is her own illustration incarnate. This is a beautiful-looking film.

The princess who wants Dorothy’s head for her own is straight out of Ozma of Oz, though in the book she’s a princess of the kingdom of Ev, not Oz. “Mombi” is the name of a witch who possesses a life-giving magical potion, which creates Jack Pumpkinhead – so you can see how the movie is faithful without being slavish. There are actually a number of touches to satisfy fans of the books, but just the art direction and costume design is enough to put a smile on the face of every Oz-ite. Renowned comic book artist Mike Ploog (Abadazad) served as illustrator and storyboard artist; along with supervising art director Charles Bishop (Young Sherlock Holmes) and art director Fred Hole (Avalon; Star Wars: Episodes I & II), the team worked to ensure that the turn-of-the-century illustrations by John R. Neill are taken as Bible. (Incidentally, a close inspection of the credits reveals that Henry Selick, later to direct The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, also did storyboard work.) Just look at the Emerald City, particularly in the finale: it looks like a scene from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair – which makes sense. Baum attended and was influenced by the Fair when he wrote the first Oz book. The cast that gathers around Scarecrow’s throne all faithfully adhere to Neill’s art, the aesthetic alternating between toy-soldier and Art Nouveau (Maxfield Parrish is clearly an influence here as well). Blink and you’ll miss cameos from other Oz characters: Santa Claus (from The Road to Oz) and – I think – the Shaggy Man and the Captain General. The Scarecrow, The Tin Man, and The Cowardly Lion are modeled after the books, not the Fleming film, and as a further gesture to fans, the Cowardly Lion even has a bow at the top of his head. Ozma (Emma Ridley once more) is her own illustration incarnate. This is a beautiful-looking film. Is it a perfect film? Not by a Yellow Brick mile. The Wheelers are distracting and look cheap compared to the effort that’s gone into the designs of the rest of the characters. There’s also something intangible but essential missing. Perhaps the filmmakers were so intent on creating a darker Oz film that they lost touch with the enchantment, the feeling of magic, that any Oz excursion requires. However memorable the opening sequences are, they seem misguided to a baffling extent. Why is it necessary for Dorothy to go through this? Why would Uncle Henry and Aunt Em ever subject their child to torture to cure her of imaginary friends? What is the film trying to say?

Is it a perfect film? Not by a Yellow Brick mile. The Wheelers are distracting and look cheap compared to the effort that’s gone into the designs of the rest of the characters. There’s also something intangible but essential missing. Perhaps the filmmakers were so intent on creating a darker Oz film that they lost touch with the enchantment, the feeling of magic, that any Oz excursion requires. However memorable the opening sequences are, they seem misguided to a baffling extent. Why is it necessary for Dorothy to go through this? Why would Uncle Henry and Aunt Em ever subject their child to torture to cure her of imaginary friends? What is the film trying to say? In the final scene, Ozma appears in Dorothy’s mirror, but when Dorothy tries to summon her parents to look, Ozma places a finger on her lips. Sssh. Don’t let the grown-ups know that you have an imagination! Maybe they’ll try lobotomy next, Dorothy – watch out. Further, it’s practically underlined that Dorothy didn’t really go to Oz. In Ozma of Oz, she visits by falling overboard on a sea voyage to Australia, and drifts in the coop until she arrives at the kingdom of Ev. But it’s made explicit in the film that she’s only been dreaming; in its closest homage to the original film, actors who appear in Kansas recur in Oz as doppelgangers (the “double” theme is echoed by Ozma’s arrival through a mirror, replacing Dorothy’s own reflection). I always bristle when fantasy has to be placed in a realistic “context” to make it palatable for skeptical viewers. It’s patronizing toward the children in the audience, for one thing, but it also betrays the childlike logic which abounds in Baum’s original novels. Baum tells the children that they’re wise, brave, and know things adults don’t know about. In 1910’s The Emerald City of Oz, Dorothy has to reassure her aunt and uncle that yes, there is an Oz – and in a remarkable scene, she saves them from their anxieties about debt and home foreclosure (!) by using Ozma’s magic to draw them into Oz so they can not only see for themselves, but spend the rest of their lives without the worries of the boring, drab, “real” world. Maybe this is why there are so many Oz films currently in development; with fears of a “double-dip recession” in the news, what we really need right now is to open up package tours to Oz. Sign me up.

In the final scene, Ozma appears in Dorothy’s mirror, but when Dorothy tries to summon her parents to look, Ozma places a finger on her lips. Sssh. Don’t let the grown-ups know that you have an imagination! Maybe they’ll try lobotomy next, Dorothy – watch out. Further, it’s practically underlined that Dorothy didn’t really go to Oz. In Ozma of Oz, she visits by falling overboard on a sea voyage to Australia, and drifts in the coop until she arrives at the kingdom of Ev. But it’s made explicit in the film that she’s only been dreaming; in its closest homage to the original film, actors who appear in Kansas recur in Oz as doppelgangers (the “double” theme is echoed by Ozma’s arrival through a mirror, replacing Dorothy’s own reflection). I always bristle when fantasy has to be placed in a realistic “context” to make it palatable for skeptical viewers. It’s patronizing toward the children in the audience, for one thing, but it also betrays the childlike logic which abounds in Baum’s original novels. Baum tells the children that they’re wise, brave, and know things adults don’t know about. In 1910’s The Emerald City of Oz, Dorothy has to reassure her aunt and uncle that yes, there is an Oz – and in a remarkable scene, she saves them from their anxieties about debt and home foreclosure (!) by using Ozma’s magic to draw them into Oz so they can not only see for themselves, but spend the rest of their lives without the worries of the boring, drab, “real” world. Maybe this is why there are so many Oz films currently in development; with fears of a “double-dip recession” in the news, what we really need right now is to open up package tours to Oz. Sign me up.