By the time Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same was finally released, the band hardly cared anymore. They needed to put something out; the car accident which had left Robert Plant and his family with severe injuries had placed the band on hiatus for too long, and their latest album, Presence, was perceived as a mild disappointment. The idea of a Led Zeppelin movie had been struck many years before, and shooting was initiated, to great expense, and then scrapped with a defeated shrug. Joe Massot, who directed the psychedelic, George Harrison-scored Wonderwall (1968), had been hired to gather footage of the band members. He filmed the four men – as well as Zeppelin manager Peter Grant and tour manager Richard Cole – as they saw themselves, often in elaborate fantasy sequences. Later, Massot was permitted to film their last performances in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, the tail-end of their 1973 American tour. The band was physically exhausted. Guitarist Jimmy Page was recovering from an injured hand, and was forcing his way through each three-hour performance as a sheer force of will. Morale was low, and midway through one of their concerts, the news reached them that someone had stolen $200,000 from their hotel room safe. They played on anyhow. Watching the footage afterward, the band thought the performance was not up to their standards. Three years later, urgently wishing to keep Led Zeppelin high in the pop culture consciousness, they hired a veteran concert film director, Peter Clifton, to piece it all together, and then decided that what they had was good enough. (The critics largely disagreed.)

By the time Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same was finally released, the band hardly cared anymore. They needed to put something out; the car accident which had left Robert Plant and his family with severe injuries had placed the band on hiatus for too long, and their latest album, Presence, was perceived as a mild disappointment. The idea of a Led Zeppelin movie had been struck many years before, and shooting was initiated, to great expense, and then scrapped with a defeated shrug. Joe Massot, who directed the psychedelic, George Harrison-scored Wonderwall (1968), had been hired to gather footage of the band members. He filmed the four men – as well as Zeppelin manager Peter Grant and tour manager Richard Cole – as they saw themselves, often in elaborate fantasy sequences. Later, Massot was permitted to film their last performances in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, the tail-end of their 1973 American tour. The band was physically exhausted. Guitarist Jimmy Page was recovering from an injured hand, and was forcing his way through each three-hour performance as a sheer force of will. Morale was low, and midway through one of their concerts, the news reached them that someone had stolen $200,000 from their hotel room safe. They played on anyhow. Watching the footage afterward, the band thought the performance was not up to their standards. Three years later, urgently wishing to keep Led Zeppelin high in the pop culture consciousness, they hired a veteran concert film director, Peter Clifton, to piece it all together, and then decided that what they had was good enough. (The critics largely disagreed.)

Still, the film has endured as a part of Led Zeppelin’s legacy, and even a “mediocre” Led Zeppelin performance is quite an experience. The central image of the film is Robert Plant’s chest and torso, exposed, slick with sweat, stretching or spasming as he moves and gestures, above it all a mop of blond curls that occasionally reveal his typically wry grin. When the camera backs up a bit, we’re left to contemplate that those tight, tight pants leave nothing to the imagination (as a Rutles mum might say). He once called himself the “golden god,” but he’s more like a living fertility idol. Beside him, Jimmy Page bows his guitar until the strings of the bow are splitting, and it resembles a tangle of wires; but he’s still pulling the most unearthly noises from it, ever the group’s mystic. John Paul Jones solemnly plays the keys or bass, seldom given a spotlight. John Bonham beats the drums…forever. He never stops. He plays his long “Moby Dick” solo so the rest of the band can leave the stage and have a respite, but he keeps at it for the whole concert. He’s like some brutal machine.

Still, the film has endured as a part of Led Zeppelin’s legacy, and even a “mediocre” Led Zeppelin performance is quite an experience. The central image of the film is Robert Plant’s chest and torso, exposed, slick with sweat, stretching or spasming as he moves and gestures, above it all a mop of blond curls that occasionally reveal his typically wry grin. When the camera backs up a bit, we’re left to contemplate that those tight, tight pants leave nothing to the imagination (as a Rutles mum might say). He once called himself the “golden god,” but he’s more like a living fertility idol. Beside him, Jimmy Page bows his guitar until the strings of the bow are splitting, and it resembles a tangle of wires; but he’s still pulling the most unearthly noises from it, ever the group’s mystic. John Paul Jones solemnly plays the keys or bass, seldom given a spotlight. John Bonham beats the drums…forever. He never stops. He plays his long “Moby Dick” solo so the rest of the band can leave the stage and have a respite, but he keeps at it for the whole concert. He’s like some brutal machine.

I’ll admit something here: I have a weakness for self-indulgent surrealistic nonsense of the late 60’s and early 70’s. The more self-indulgent the better. The film’s most astoundingly naked flaw is Massot’s prolonged fantasy sequences, filming whatever the band thought might be kind of cool. This is what led to Magical Mystery Tour (1967), folks. Richard Lester knew what would make a good film; the Beatles, free of his guiding hand, did not. And Led Zeppelin was clearly spitballing; Massot just went with it. What you get is some pretty weird, goofy material, much of it attractively filmed. The film opens with its most bizarre sequence, because…where else are you going to put it? I mean, really? Peter Grant and Richard Cole are dressed as 1930’s gangsters, with the requisite tommy guns. They exit a country estate and board a 30’s car with grim faces – that’s right, something real is going down, and I doubt it has anything to do with Led Zeppelin. Elsewhere, some gangsters are playing a strange board game (it looks like it’s based on The Great Escape) for cash. One of the players has no face. Another is a werewolf. Grant and Cole and their lackeys burst into the room and exchange gunfire. The werewolf goes down in slow motion, screaming; it’s spectacular. An old gangster fires dispassionately with his revolver. His head is shot off; it goes tumbling to the table, and out of his neck spew multi-colored streams of ink. Take notes, there will be a test later.

It’s telling that Grant and Cole saw themselves as glorious mobsters. It also reflects their reputation. Grant set a precedent when he demanded that 90% of the profits from each concert go directly to the band. Led Zeppelin entered each city like a pirate raid, and Grant and Cole were the captain and his first mate. The film occasionally cuts to backstage footage, and we see how Grant holds his ground and firmly confronts the theater management about the sale of bootlegged Zeppelin posters. He points aggressively with a hand heavily outfitted with oversized rings: pure intimidation. It’s easy to see how Tony Hendra could borrow liberally from this scene for his performance as the volatile, fiercely protective manager Ian in This is Spinal Tap (1984).

It’s telling that Grant and Cole saw themselves as glorious mobsters. It also reflects their reputation. Grant set a precedent when he demanded that 90% of the profits from each concert go directly to the band. Led Zeppelin entered each city like a pirate raid, and Grant and Cole were the captain and his first mate. The film occasionally cuts to backstage footage, and we see how Grant holds his ground and firmly confronts the theater management about the sale of bootlegged Zeppelin posters. He points aggressively with a hand heavily outfitted with oversized rings: pure intimidation. It’s easy to see how Tony Hendra could borrow liberally from this scene for his performance as the volatile, fiercely protective manager Ian in This is Spinal Tap (1984).

The music-free, excessively curious opening scenes also portray Robert Plant and family in a country idyll (his nude children frolic in a creek); classic-car collector John Bonham working on his Model T; John Paul Jones, in Prince Valiant hair, reading “Jack and the Beanstalk” to his children at bedtime; and Jimmy Page, sitting on an Oriental rug beside his guitar, sunglasses glowing bright orange as though he’s been possessed by some pagan god of rock and roll. Like superheroes being summoned back to the Justice League headquarters, each of the men is delivered a list of tour dates – and so they’re off to New York in their private jet (with the words “Led Zeppelin” painted on the side; they called it the Starship). During the performance, hallucinatory interludes take us away from Madison Square Garden and to: Robert Plant receiving a sword and embarking upon an epic quest, battling knights in a castle; a horse-mounted John Paul Jones wearing a fright mask and stalking a young woman; John Bonham drag racing (appropriately set during his propulsive drum solo); and Jimmy Page climbing a mountain to confront the old hermit of the Tarot, who swings a psychedelic sword, de-ages into Page himself, and then further, into a Star Child-like fetus – and back to an old man again. Heavy stuff.

The music-free, excessively curious opening scenes also portray Robert Plant and family in a country idyll (his nude children frolic in a creek); classic-car collector John Bonham working on his Model T; John Paul Jones, in Prince Valiant hair, reading “Jack and the Beanstalk” to his children at bedtime; and Jimmy Page, sitting on an Oriental rug beside his guitar, sunglasses glowing bright orange as though he’s been possessed by some pagan god of rock and roll. Like superheroes being summoned back to the Justice League headquarters, each of the men is delivered a list of tour dates – and so they’re off to New York in their private jet (with the words “Led Zeppelin” painted on the side; they called it the Starship). During the performance, hallucinatory interludes take us away from Madison Square Garden and to: Robert Plant receiving a sword and embarking upon an epic quest, battling knights in a castle; a horse-mounted John Paul Jones wearing a fright mask and stalking a young woman; John Bonham drag racing (appropriately set during his propulsive drum solo); and Jimmy Page climbing a mountain to confront the old hermit of the Tarot, who swings a psychedelic sword, de-ages into Page himself, and then further, into a Star Child-like fetus – and back to an old man again. Heavy stuff.

There’s plenty of time for all this, because Led Zeppelin, live, stretched their songs to the absolute limit, improvising, keeping themselves amused. “Stairway to Heaven,” so rigorously structured, is kept intact, but the film’s centerpiece is a performance of “Dazed and Confused” which drifts happily off course for half an hour, with Plant at one point even singing a bit of Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” Eventually, after guitar solo after guitar solo, the trademark monster riff of “Dazed and Confused” is flown back in, and they close where they began. They saw their music as a Tolkienesque journey, and the vast mobs that gathered before their stage were eager to go with them, wherever it led (thus all the lyrics about Viking raids and Mordor). So it’s appropriate that Peter Clifton uses all of Joe Massot’s non-concert footage as “head trip” moments to goose the concert material; we’re on a long trip, after all – might as well give the audience something fresh to look at while the music plays.

There’s plenty of time for all this, because Led Zeppelin, live, stretched their songs to the absolute limit, improvising, keeping themselves amused. “Stairway to Heaven,” so rigorously structured, is kept intact, but the film’s centerpiece is a performance of “Dazed and Confused” which drifts happily off course for half an hour, with Plant at one point even singing a bit of Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” Eventually, after guitar solo after guitar solo, the trademark monster riff of “Dazed and Confused” is flown back in, and they close where they began. They saw their music as a Tolkienesque journey, and the vast mobs that gathered before their stage were eager to go with them, wherever it led (thus all the lyrics about Viking raids and Mordor). So it’s appropriate that Peter Clifton uses all of Joe Massot’s non-concert footage as “head trip” moments to goose the concert material; we’re on a long trip, after all – might as well give the audience something fresh to look at while the music plays.

Naturally, the straightforward concert footage has aged much better. Even if it doesn’t capture the band at its best, it does grab them at their height, with all their innovations on display. Plant, for example, playfully imitating Page’s hammer-struck chords with some borderline scatting. The intuitive way all four members of the band can improvise together, exploring without ever losing sight of the path. The bowing, the double-neck guitar, the on-stage explosions and light shows that would later become the standard for big heavy metal shows. For the finale of their finale, “Whole Lotta Love,” the gong behind John Bonham bursts into flames, and he pounds it with a flaming drumstick. Massot’s crew captures Plant posing before the flaming gong, bathed in the murky glow of a green spotlight. After that, there’s nowhere left to go. They bid the sweating masses farewell, and we follow the pirate-ship Led Zeppelin backstage, marching at a swift pace. Page wears a particularly ecstatic smile: another village sacked and burned to the ground.

Naturally, the straightforward concert footage has aged much better. Even if it doesn’t capture the band at its best, it does grab them at their height, with all their innovations on display. Plant, for example, playfully imitating Page’s hammer-struck chords with some borderline scatting. The intuitive way all four members of the band can improvise together, exploring without ever losing sight of the path. The bowing, the double-neck guitar, the on-stage explosions and light shows that would later become the standard for big heavy metal shows. For the finale of their finale, “Whole Lotta Love,” the gong behind John Bonham bursts into flames, and he pounds it with a flaming drumstick. Massot’s crew captures Plant posing before the flaming gong, bathed in the murky glow of a green spotlight. After that, there’s nowhere left to go. They bid the sweating masses farewell, and we follow the pirate-ship Led Zeppelin backstage, marching at a swift pace. Page wears a particularly ecstatic smile: another village sacked and burned to the ground.

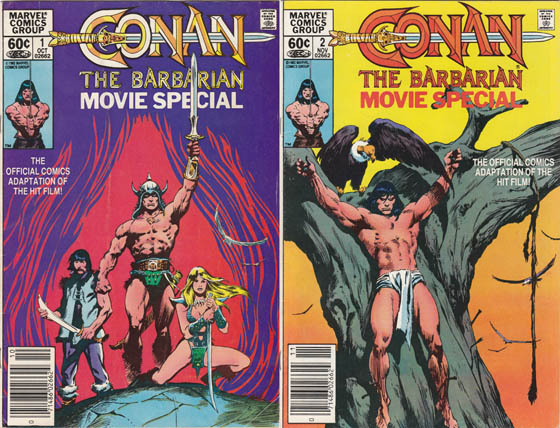

Conan and I go way back. My first impression of the character was when I went to Universal Studios in California in 1983, just a wee tyke, taking notice of the brochure’s advertisement for the Conan the Barbarian stunt show that featured a sword-wielding muscleman battling a giant serpent in a temple. We didn’t go (but I did get to battle Cylons in the Battlestar Galactica section of the tram tour, and had my picture taken next to Jaws and Frankenstein’s monster). A few years later we moved to Wisconsin. General Mitchell, the Milwaukee airport, had (has?) a great used bookstore called Renaissance Books, and whenever we were about to fly somewhere I’d take time out to rummage through their books and comics. There I found a small paperback omnibus of the first couple of issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Barry Windsor-Smith. Associating it immediately with that awesome-looking Universal Studios show, and satisfied that it began with issue #1, I picked it up. A short time later I was reading the Lancer/Ace paperbacks with the Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo covers, compiling the original 1930’s Weird Tales Conan stories of Robert E. Howard, plus fill-in-the-gaps pastiches by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. At the larger version of Renaissance Books in downtown Milwaukee, I found a back issue of The Savage Sword of Conan, and was mesmerized by the violence and sex in beautiful black-and-white. I started collecting the ongoing monthly Conan titles as well. My Trapper Keeper that I took to school was decorated with Savage Sword pin-ups by Ernie Chan. I was a fan of ALF (who wasn’t?), and wrote to the ALF comic book asking that they do a Conan parody. They printed my letter, and complied by running an ALF story called “Gordon the Barbarian” or whatever. Those last two sentences weren’t written with pride.

Conan and I go way back. My first impression of the character was when I went to Universal Studios in California in 1983, just a wee tyke, taking notice of the brochure’s advertisement for the Conan the Barbarian stunt show that featured a sword-wielding muscleman battling a giant serpent in a temple. We didn’t go (but I did get to battle Cylons in the Battlestar Galactica section of the tram tour, and had my picture taken next to Jaws and Frankenstein’s monster). A few years later we moved to Wisconsin. General Mitchell, the Milwaukee airport, had (has?) a great used bookstore called Renaissance Books, and whenever we were about to fly somewhere I’d take time out to rummage through their books and comics. There I found a small paperback omnibus of the first couple of issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Barry Windsor-Smith. Associating it immediately with that awesome-looking Universal Studios show, and satisfied that it began with issue #1, I picked it up. A short time later I was reading the Lancer/Ace paperbacks with the Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo covers, compiling the original 1930’s Weird Tales Conan stories of Robert E. Howard, plus fill-in-the-gaps pastiches by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. At the larger version of Renaissance Books in downtown Milwaukee, I found a back issue of The Savage Sword of Conan, and was mesmerized by the violence and sex in beautiful black-and-white. I started collecting the ongoing monthly Conan titles as well. My Trapper Keeper that I took to school was decorated with Savage Sword pin-ups by Ernie Chan. I was a fan of ALF (who wasn’t?), and wrote to the ALF comic book asking that they do a Conan parody. They printed my letter, and complied by running an ALF story called “Gordon the Barbarian” or whatever. Those last two sentences weren’t written with pride. And somewhere along the way, I saw Conan the Barbarian (1982) – first on television in edited form, and then, almost illicitly, at a friend’s house during a sleepover. He had HBO! He had the R-rated cut! My parents had a strict PG-only policy. To have Conan the Barbarian be the first R-rated film I ever saw boggled my little head. When Conan swept his steel sword, geysers of red blood burst from the torsos and necks and limbs of his adversaries. Slave girls dropped their fur cloaks and submitted to his desires. At a semi-nude orgy, the cultists of Set participate in cannibalism, and James Earl Jones turns into a snake. Is this what all R-rated movies were like? What a world I had waiting for me!

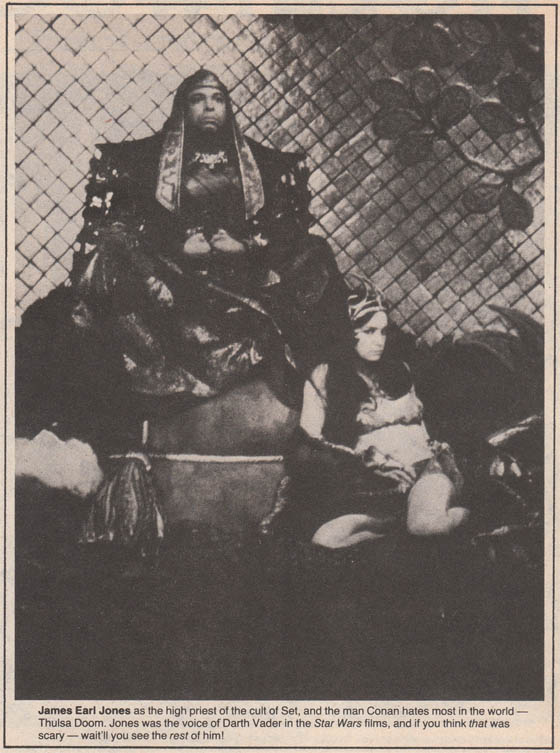

And somewhere along the way, I saw Conan the Barbarian (1982) – first on television in edited form, and then, almost illicitly, at a friend’s house during a sleepover. He had HBO! He had the R-rated cut! My parents had a strict PG-only policy. To have Conan the Barbarian be the first R-rated film I ever saw boggled my little head. When Conan swept his steel sword, geysers of red blood burst from the torsos and necks and limbs of his adversaries. Slave girls dropped their fur cloaks and submitted to his desires. At a semi-nude orgy, the cultists of Set participate in cannibalism, and James Earl Jones turns into a snake. Is this what all R-rated movies were like? What a world I had waiting for me!

Odd that the list was so short, because sword-and-sorcery was all the rage through the 70’s, reaching its peak of excitement in the early 80’s. Wizards and warriors were all over paperback books and comics; posters by Frank Frazetta and of Tolkien’s Middle Earth were hung beside pin-ups of rock and roll stars, and those same fanboys might also paint the side of their vans in Frazetta-esque imagery; “Dungeons & Dragons” took hold of pop culture and briefly caused an absurd hysteria that it was a cult brainwashing the young (my own mother was convinced that D&D and Satanism were synonymous, which is why I never played role-playing games). In the early 70’s, when Marvel’s Roy Thomas tried to convince Stan Lee that Conan was a property they should license, it was a hard sell. But very soon it was one of their tentpole comics, a hit that spawned spin-offs like Red Sonja and Kull the Conqueror, and even a daily newspaper comic strip. For years there was talk of a Conan movie; even stop-motion maestro Ray Harryhausen wanted to make one, at some point or another. John Milius, who had written Apocalypse Now (1979), was finally attached to direct a script that had been written by Oliver Stone. Arnold Schwarzenegger was cast as Conan; he’d acted in a few films (like 1976’s Stay Hungry), but was still best known as that really-ripped bodybuilder from the documentary Pumping Iron (1977). Conan the Barbarian made him a bona fide movie star.

Odd that the list was so short, because sword-and-sorcery was all the rage through the 70’s, reaching its peak of excitement in the early 80’s. Wizards and warriors were all over paperback books and comics; posters by Frank Frazetta and of Tolkien’s Middle Earth were hung beside pin-ups of rock and roll stars, and those same fanboys might also paint the side of their vans in Frazetta-esque imagery; “Dungeons & Dragons” took hold of pop culture and briefly caused an absurd hysteria that it was a cult brainwashing the young (my own mother was convinced that D&D and Satanism were synonymous, which is why I never played role-playing games). In the early 70’s, when Marvel’s Roy Thomas tried to convince Stan Lee that Conan was a property they should license, it was a hard sell. But very soon it was one of their tentpole comics, a hit that spawned spin-offs like Red Sonja and Kull the Conqueror, and even a daily newspaper comic strip. For years there was talk of a Conan movie; even stop-motion maestro Ray Harryhausen wanted to make one, at some point or another. John Milius, who had written Apocalypse Now (1979), was finally attached to direct a script that had been written by Oliver Stone. Arnold Schwarzenegger was cast as Conan; he’d acted in a few films (like 1976’s Stay Hungry), but was still best known as that really-ripped bodybuilder from the documentary Pumping Iron (1977). Conan the Barbarian made him a bona fide movie star. Milius shot in Spain, using a largely Spanish crew, and considering that the majority of the film takes place outdoors, the locations used to represent “the Hyborian Age” are spectacular, right from the very start. The film begins in wintry Cimmeria, where the young Conan (Jorge Sanz, with no dialogue but soulful eyes) is raised in a small village by his father (William Smith) to worship the grim god Crom and seek out the “riddle of steel.” After this opening monologue (and an on-screen quote from Nietzsche!), we’re witness to Conan’s village being razed to the ground by a band of raiders. Leading these men is Thulsa Doom, played by James Earl Jones, doubtless cast because of his recognizably sonorous Darth Vader voice. Thulsa Doom was actually a character from Howard’s Kull stories, which take place thousands of years before the Conan tales; so Jones wears blue contact lenses to underline his “lost race” ancestry. He clearly relishes the opportunity to play a villain with more than just his voice. He’s introduced with no dialogue, just a confrontation with Conan and his mother (Nadiuska), drawn out Sergio Leone-style, in which he first mesmerizes the woman, then swiftly decapitates her.

Milius shot in Spain, using a largely Spanish crew, and considering that the majority of the film takes place outdoors, the locations used to represent “the Hyborian Age” are spectacular, right from the very start. The film begins in wintry Cimmeria, where the young Conan (Jorge Sanz, with no dialogue but soulful eyes) is raised in a small village by his father (William Smith) to worship the grim god Crom and seek out the “riddle of steel.” After this opening monologue (and an on-screen quote from Nietzsche!), we’re witness to Conan’s village being razed to the ground by a band of raiders. Leading these men is Thulsa Doom, played by James Earl Jones, doubtless cast because of his recognizably sonorous Darth Vader voice. Thulsa Doom was actually a character from Howard’s Kull stories, which take place thousands of years before the Conan tales; so Jones wears blue contact lenses to underline his “lost race” ancestry. He clearly relishes the opportunity to play a villain with more than just his voice. He’s introduced with no dialogue, just a confrontation with Conan and his mother (Nadiuska), drawn out Sergio Leone-style, in which he first mesmerizes the woman, then swiftly decapitates her.

After an interlude adapted from L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter’s story “The Thing in the Crypt” (de Camp served as “technical advisor” on the film), and a sexual encounter with a witch that ends with a female orgasm, flashy special effects, and immolation, Conan frees a thief named Subotai (the endearingly laconic Gerry Lopez), and together they journey out of the wilderness and toward civilization, in the kingdom of Zamora. Subotai wants to find some treasure to steal, but Conan’s more interested in tracking down Thulsa Doom to avenge his parents’ murder. They quickly learn that Doom’s snake-worshiping cult is spreading throughout the country. While infiltrating one of the cult strongholds, the Tower of the Serpent, they meet Valeria (Sandahl Bergman), a swordswoman and thief. After a successful raid (and a battle in which Conan faces a giant snake), they become fabulously wealthy, attracting the attention of King Osric (Max Von Sydow), who pleads with them to steal into Thulsa Doom’s lair and rescue his daughter (Valérie Quennessen), who has fallen under Doom’s thrall. Conan decides to set out alone on this suicide mission, though soon enough he requires the help of Valeria and Subotai, as well as an eccentric old wizard (Mako) – who also happens to be narrating the film.

After an interlude adapted from L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter’s story “The Thing in the Crypt” (de Camp served as “technical advisor” on the film), and a sexual encounter with a witch that ends with a female orgasm, flashy special effects, and immolation, Conan frees a thief named Subotai (the endearingly laconic Gerry Lopez), and together they journey out of the wilderness and toward civilization, in the kingdom of Zamora. Subotai wants to find some treasure to steal, but Conan’s more interested in tracking down Thulsa Doom to avenge his parents’ murder. They quickly learn that Doom’s snake-worshiping cult is spreading throughout the country. While infiltrating one of the cult strongholds, the Tower of the Serpent, they meet Valeria (Sandahl Bergman), a swordswoman and thief. After a successful raid (and a battle in which Conan faces a giant snake), they become fabulously wealthy, attracting the attention of King Osric (Max Von Sydow), who pleads with them to steal into Thulsa Doom’s lair and rescue his daughter (Valérie Quennessen), who has fallen under Doom’s thrall. Conan decides to set out alone on this suicide mission, though soon enough he requires the help of Valeria and Subotai, as well as an eccentric old wizard (Mako) – who also happens to be narrating the film. Milius decided to cast his principals by physical type, rather than acting ability, and for better or worse, that decision defines the film. Schwarzenegger was a bodybuilder, Bergman a dancer, Lopez a surfer. This means that Conan looks like the Conan of the comic books, and Bergman and Lopez are lithe and athletic. Still, just when you get settled into their level of performance, along comes The Seventh Seal‘s Max Von Sydow, playing Osric like he’s in a Royal Shakespeare Company production of King Lear, and the effect is jarring. Similarly, when James Earl Jones moves to center stage a few scenes later, his monologues are powerful and spellbinding (exactly what Thulsa Doom needs to be). The two actors steal the film, by default as much as by merit. Now, maybe the inexperienced Schwarzenegger would have been upstaged in every scene if his two loyal companions were professional actors, but when Von Sydow and Jones are on screen, it’s hard not to think that the movie needs more of this.

Milius decided to cast his principals by physical type, rather than acting ability, and for better or worse, that decision defines the film. Schwarzenegger was a bodybuilder, Bergman a dancer, Lopez a surfer. This means that Conan looks like the Conan of the comic books, and Bergman and Lopez are lithe and athletic. Still, just when you get settled into their level of performance, along comes The Seventh Seal‘s Max Von Sydow, playing Osric like he’s in a Royal Shakespeare Company production of King Lear, and the effect is jarring. Similarly, when James Earl Jones moves to center stage a few scenes later, his monologues are powerful and spellbinding (exactly what Thulsa Doom needs to be). The two actors steal the film, by default as much as by merit. Now, maybe the inexperienced Schwarzenegger would have been upstaged in every scene if his two loyal companions were professional actors, but when Von Sydow and Jones are on screen, it’s hard not to think that the movie needs more of this. Jones’ speech about the “riddle of steel,” in which he lures one of his acolytes to jump to her death, is effectively chilling: he’s less Darth Vader than Charles Manson. And like Manson, his followers are hippies, youths who have abandoned their parents to don white robs and flowers, practicing meditation and mindlessly chanting “Dooooom” at their great magical leader. It’s a strange choice, but the idea that the followers of doom are equivalent to the Manson Family is underlined time and again, particularly in Von Sydow’s voiced horror that his brainwashed daughter might come back and murder him on Doom’s command. The analogy also leads to some nice parody when Conan first arrives in Doom’s camp, and tries to blend in amongst the dopey flock – as much as an Arnold Schwarzenegger can. This introduces the film’s most spectacular set: a temple in the mountains, giant steps cast down from it, at the bottom of which hundreds of extras gather. The climax gives Milius a chance to shoot this set at night, with each of the cultists holding a candle, recasting Thulsa Doom not as Charles Manson but as a rock and roll idol, looking down upon his audience who might as well be holding up cigarette lighters in allegiance to his song.

Jones’ speech about the “riddle of steel,” in which he lures one of his acolytes to jump to her death, is effectively chilling: he’s less Darth Vader than Charles Manson. And like Manson, his followers are hippies, youths who have abandoned their parents to don white robs and flowers, practicing meditation and mindlessly chanting “Dooooom” at their great magical leader. It’s a strange choice, but the idea that the followers of doom are equivalent to the Manson Family is underlined time and again, particularly in Von Sydow’s voiced horror that his brainwashed daughter might come back and murder him on Doom’s command. The analogy also leads to some nice parody when Conan first arrives in Doom’s camp, and tries to blend in amongst the dopey flock – as much as an Arnold Schwarzenegger can. This introduces the film’s most spectacular set: a temple in the mountains, giant steps cast down from it, at the bottom of which hundreds of extras gather. The climax gives Milius a chance to shoot this set at night, with each of the cultists holding a candle, recasting Thulsa Doom not as Charles Manson but as a rock and roll idol, looking down upon his audience who might as well be holding up cigarette lighters in allegiance to his song. Here is my theory, or at least my excuse for why I unabashedly love this film: the star is not Arnold Schwarzenegger, who hardly has any dialogue, and spends most of his time brooding in that melancholy way that R.E.H. liked to write about. No, the real star is Basil Poledouris, whose score is surely is one of the greatest ever written for a motion picture. Now finally remixed in 5.1 for the new Blu-Ray edition, it roars, swoons, waltzes, and swashbuckles. He wears his influences – in particular Wagner, as well as Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade – on his sleeve, and it’s unapologetically romantic in a way that all adventure films ought to be. This was a golden age for film music. With John Williams’ work on Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), and Superman (1978), lush orchestration was fashionable in soundtracks again (The Graduate had made contemporary pop music the de rigueur movie composer for a good decade). Thus, Poledouris had permission to go all-out, and his themes, from the muscle-flexing opening title march (“Anvil of Crom”), to the rousing music accompanying the journey to Zamora, and the honey-sweet waltz that plays during Thulsa Doom’s orgy, are all uniquely memorable. His score works overtime, sometimes nearly drowning out Schwarzenegger’s poor line delivery, as though overcompensating. When Conan and Valeria consummate their feelings, the sweaty, grunty sex scene is scored with a theme that swells with a feeling of tragedy, as Poledouris foreshadows their eventual separation. (Incidentally, the theme is called “Wifeing”!)

Here is my theory, or at least my excuse for why I unabashedly love this film: the star is not Arnold Schwarzenegger, who hardly has any dialogue, and spends most of his time brooding in that melancholy way that R.E.H. liked to write about. No, the real star is Basil Poledouris, whose score is surely is one of the greatest ever written for a motion picture. Now finally remixed in 5.1 for the new Blu-Ray edition, it roars, swoons, waltzes, and swashbuckles. He wears his influences – in particular Wagner, as well as Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade – on his sleeve, and it’s unapologetically romantic in a way that all adventure films ought to be. This was a golden age for film music. With John Williams’ work on Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), and Superman (1978), lush orchestration was fashionable in soundtracks again (The Graduate had made contemporary pop music the de rigueur movie composer for a good decade). Thus, Poledouris had permission to go all-out, and his themes, from the muscle-flexing opening title march (“Anvil of Crom”), to the rousing music accompanying the journey to Zamora, and the honey-sweet waltz that plays during Thulsa Doom’s orgy, are all uniquely memorable. His score works overtime, sometimes nearly drowning out Schwarzenegger’s poor line delivery, as though overcompensating. When Conan and Valeria consummate their feelings, the sweaty, grunty sex scene is scored with a theme that swells with a feeling of tragedy, as Poledouris foreshadows their eventual separation. (Incidentally, the theme is called “Wifeing”!) But Poledouris is not the only one working hard to make Conan the Barbarian a film to last. Milius treats the source material with fanboyish respect, and even if he occasionally rewrites Conan lore to suit the cinematic telling, he draws equally from Robert E. Howard, the comics and pastiches, Frazetta paintings (one of which is explicitly reproduced in the film, if you look fast), Norse mythology, Sergio Leone Westerns, and Japanese cinema to craft a film that resonates with a seriousness to match its score. To that latter category, the climax has the feel of Kurosawa’s samurai films, in particular Seven Samurai (1954), and there’s a most explicit homage to the great Japanese ghost story Kwaidan (1964), when Mako’s wizard inks runic writing onto Conan’s face to protect his unconscious body from evil spirits. Those spirits are cel-animated, in a pre-CG touch, and the way they’re portrayed, anatomy like charcoal pencil drawings, brings to mind the Marvel comics. Though Conan is a bit too dim-witted to represent the Conan Robert E. Howard fans know and love, the character of Valeria is lifted from Howard’s classic story “Red Nails” pretty intact, and her relationship with Conan recalls “Queen of the Black Coast.” Passing references to other kingdoms from the stories, like Aquilonia and Hyrkania, wink to the fans, as does the black-lotus dealer who peddles it like heroin (which it pretty much is).

But Poledouris is not the only one working hard to make Conan the Barbarian a film to last. Milius treats the source material with fanboyish respect, and even if he occasionally rewrites Conan lore to suit the cinematic telling, he draws equally from Robert E. Howard, the comics and pastiches, Frazetta paintings (one of which is explicitly reproduced in the film, if you look fast), Norse mythology, Sergio Leone Westerns, and Japanese cinema to craft a film that resonates with a seriousness to match its score. To that latter category, the climax has the feel of Kurosawa’s samurai films, in particular Seven Samurai (1954), and there’s a most explicit homage to the great Japanese ghost story Kwaidan (1964), when Mako’s wizard inks runic writing onto Conan’s face to protect his unconscious body from evil spirits. Those spirits are cel-animated, in a pre-CG touch, and the way they’re portrayed, anatomy like charcoal pencil drawings, brings to mind the Marvel comics. Though Conan is a bit too dim-witted to represent the Conan Robert E. Howard fans know and love, the character of Valeria is lifted from Howard’s classic story “Red Nails” pretty intact, and her relationship with Conan recalls “Queen of the Black Coast.” Passing references to other kingdoms from the stories, like Aquilonia and Hyrkania, wink to the fans, as does the black-lotus dealer who peddles it like heroin (which it pretty much is). Though some purists turn up their nose at this film, there’s enough here of quality that most fans have embraced it; indeed, many Conan fans have come to the character through this film like a gateway drug. So it’s gained some nostalgia value over the years, but it’s also, oddly, gained in stature when all of its sequels and rip-offs have fallen short. Conan the Barbarian was part of a short-lived surge of barbarian movies. Cluttered around it were the likes of The Beastmaster (1982), Ator, the Fighting Eagle (1982), The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982), Fire & Ice (1983), Deathstalker (1983), and The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984). Over the years, unless it was a permanent part of your video library, you were likely to forget that Conan the Barbarian was better than those films, and much better than its own campy follow-ups, Conan the Destroyer (1984) and Red Sonja (1985). There’s an integrity to the original film, one that’s likely to be lacking in the upcoming remake. John Milius, Oliver Stone, Basil Poledouris, and James Earl Jones all cared deeply – some would argue, too deeply – about making this project stand out. With adult eyes, it’s not bad at all. If you’re an adolescent boy, there’s nothing better in the land.

Though some purists turn up their nose at this film, there’s enough here of quality that most fans have embraced it; indeed, many Conan fans have come to the character through this film like a gateway drug. So it’s gained some nostalgia value over the years, but it’s also, oddly, gained in stature when all of its sequels and rip-offs have fallen short. Conan the Barbarian was part of a short-lived surge of barbarian movies. Cluttered around it were the likes of The Beastmaster (1982), Ator, the Fighting Eagle (1982), The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982), Fire & Ice (1983), Deathstalker (1983), and The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984). Over the years, unless it was a permanent part of your video library, you were likely to forget that Conan the Barbarian was better than those films, and much better than its own campy follow-ups, Conan the Destroyer (1984) and Red Sonja (1985). There’s an integrity to the original film, one that’s likely to be lacking in the upcoming remake. John Milius, Oliver Stone, Basil Poledouris, and James Earl Jones all cared deeply – some would argue, too deeply – about making this project stand out. With adult eyes, it’s not bad at all. If you’re an adolescent boy, there’s nothing better in the land.