Revenge of the Cheerleaders (1976) suggests a lesson. If you’re going to make a drive-in exploitation flick, take the opportunity seriously, but not the film. And this is a movie that makes the most of its opportunity. It proudly flies its freak flag. It is stupid and bizarre without apology. I vote Revenge of the Cheerleaders for class president.

Revenge of the Cheerleaders (1976) suggests a lesson. If you’re going to make a drive-in exploitation flick, take the opportunity seriously, but not the film. And this is a movie that makes the most of its opportunity. It proudly flies its freak flag. It is stupid and bizarre without apology. I vote Revenge of the Cheerleaders for class president.

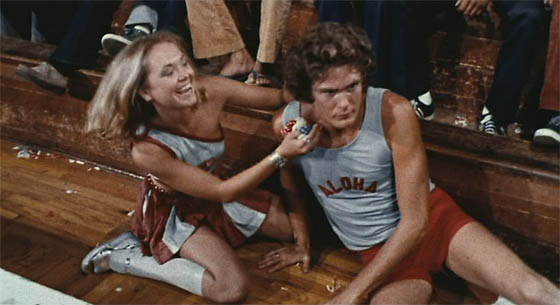

A kind-of third film in a kind-of trilogy (following 1973’s The Cheerleaders and 1974’s The Swinging Cheerleaders), Revenge acts like the Mad Magazine take on the earlier films. Aloha High School is a bacchanal of sex and drugs in the hallways and classrooms; the front lawn looks like Woodstock, with pitched tents, suntanning, more sex and drugs, and impromptu dance numbers set to funk music. In this apocalyptic vision, the cheerleaders (Susie Elene, Jerii Woods, Helen Lang, Patrice Rohmer, and a very pregnant Cheryl “Rainbeaux” Smith) are the jointly-ruling Queens, with no equivalent King at their side. Unless you count “Boner”, played by David Hasselhoff. I could type that sentence again, but you’ve already read it twice. When the gang is not at school tirelessly being irresponsible, they’re hanging out at a diner called Lilly’s, probably either having sex or dancing. In this clip, set to the unforgettable song “Come to the Party,” it’s evident why Hasselhoff would be asked onto “Dancing with the Stars” a few decades later (his solo grooves begin at 2:15):

A kind-of third film in a kind-of trilogy (following 1973’s The Cheerleaders and 1974’s The Swinging Cheerleaders), Revenge acts like the Mad Magazine take on the earlier films. Aloha High School is a bacchanal of sex and drugs in the hallways and classrooms; the front lawn looks like Woodstock, with pitched tents, suntanning, more sex and drugs, and impromptu dance numbers set to funk music. In this apocalyptic vision, the cheerleaders (Susie Elene, Jerii Woods, Helen Lang, Patrice Rohmer, and a very pregnant Cheryl “Rainbeaux” Smith) are the jointly-ruling Queens, with no equivalent King at their side. Unless you count “Boner”, played by David Hasselhoff. I could type that sentence again, but you’ve already read it twice. When the gang is not at school tirelessly being irresponsible, they’re hanging out at a diner called Lilly’s, probably either having sex or dancing. In this clip, set to the unforgettable song “Come to the Party,” it’s evident why Hasselhoff would be asked onto “Dancing with the Stars” a few decades later (his solo grooves begin at 2:15):

Back at school, the cheerleaders attend to a rigorous work ethic, which includes having sex, dancing, and breaking into classrooms to hold teacher and students hostage with a fire extinguisher until they turn over all their liquor, pills, and pot. Then they take those drugs and mix them into the cafeteria’s spaghetti sauce, to be served to the faculty and schoolkids. This special sauce would probably put a large bull into a permanent coma, but at Aloha High it only instigates an epic food fight, ending with the zonked-out, elderly school inspectors wandering into the showers for group sex with the cheerleaders and basketball team, all partially hidden beneath mountains of soapy bubbles (“Rainbeaux” Smith, still very pregnant, gets naked and joins the equal-opportunity orgy).

With so much to do, it’s a wonder the cheerleaders find time to hang out and smoke pot at basketball practice, objectifying the shirtless players (including the Hoff) with leering comments that adhere to a basketball theme. The very pregnant “Rainbeaux” Smith lights up and joins in: “When he shoots – I mean, ‘swish!'”

There’s a plot, I should mention. Lincoln High, personified by a smug group of evil Lincoln cheerleaders and an evil industrial developer, plot to put an end to Aloha High, the latter so he can build a shopping mall. (One of the LH cheerleaders proclaims, “We’re gonna make you slaves to Lincoln!”) To save the school, Aloha brings in a new principal, who’s treated to a tour which must, to his eyes, resemble the final days of Caligula’s reign.

The cheerleaders, isolated as the chief perpetrator’s of the school’s corruption, are booted off the school team and replaced with cheerleaders so awful they won’t even put out, including the spoiled daughter of the evil industrialist, Walter Hartlander. Bummed out, the girls take a field trip to the woods, where two of them are nearly arrested for strolling around naked (luckily, the other cheerleaders knock the cop unconscious and run away). Later they seduce a boy scout just because.

The cheerleaders, isolated as the chief perpetrator’s of the school’s corruption, are booted off the school team and replaced with cheerleaders so awful they won’t even put out, including the spoiled daughter of the evil industrialist, Walter Hartlander. Bummed out, the girls take a field trip to the woods, where two of them are nearly arrested for strolling around naked (luckily, the other cheerleaders knock the cop unconscious and run away). Later they seduce a boy scout just because.

When they return to school, the basketball team is losing the match to Lincoln High because the cheerleading is so uninspiring. Our heroes arrive just in time: they jam the cheerleaders into the lockers, suit up in sexy outfits, and ra-ra-ra the team toward victory. At one point, evil Nurse Beam (Eddra Gale) chloroforms Boner. But one of the cheerleaders revives the Hoff by removing her panties and using them like smelling salts. So revived, Boner leaps back onto the court, and Lincoln’s team is defeated.

When they return to school, the basketball team is losing the match to Lincoln High because the cheerleading is so uninspiring. Our heroes arrive just in time: they jam the cheerleaders into the lockers, suit up in sexy outfits, and ra-ra-ra the team toward victory. At one point, evil Nurse Beam (Eddra Gale) chloroforms Boner. But one of the cheerleaders revives the Hoff by removing her panties and using them like smelling salts. So revived, Boner leaps back onto the court, and Lincoln’s team is defeated.

Nurse Beam, secretly working for Hartlander, plants explosives in the dead of night, and the next morning the students are distraught to find Aloha High blown to smithereens. I mean, this isn’t Rock ‘n’ Roll High School‘s Vince Lombardi High – this is Aloha High, the place where they hung out and had sex and did drugs and danced. When the cheerleaders uncover evidence that their principal has been taken hostage down at the park with the giant brontosaurus, the gang hops in their convertible and goes to the rescue. What follows is a chase scene lifted straight out of Scooby-Doo (and note the use of library music borrowed from an old pulp serial):

Nurse Beam, secretly working for Hartlander, plants explosives in the dead of night, and the next morning the students are distraught to find Aloha High blown to smithereens. I mean, this isn’t Rock ‘n’ Roll High School‘s Vince Lombardi High – this is Aloha High, the place where they hung out and had sex and did drugs and danced. When the cheerleaders uncover evidence that their principal has been taken hostage down at the park with the giant brontosaurus, the gang hops in their convertible and goes to the rescue. What follows is a chase scene lifted straight out of Scooby-Doo (and note the use of library music borrowed from an old pulp serial):

Nurse Beam drags her hostage into a nearby cave, and the girls pursue deep into the winding tunnels. Out of nowhere, they discover an elevator behind a broken cave wall:

The elevator ends at a shopping mall, and the girls dash up the escalators in pursuit of Beam and her captive. Finally, Beam arrives at a golf course, where she stumbles into quicksand, which you will find at golf courses. Through the quicksand she sinks, straight into the office of evil industrialist Walter Hartlander, who looks upset that he was not informed he’d be inserted into a live-action Terry Gilliam cartoon.

The cheerleaders have saved the day. Aloha High can return to its prominence as a safe haven of sex, drugs, and funky dancing, which comes in the form of some nude and semi-nude gyrating at a high school dance while the credits roll. But that’s not all, folks. Stick through the credits for a cameo by a very not pregnant Cheryl “Rainbeaux” Smith, proudly displaying her newborn child. This is what you call a happy ending.

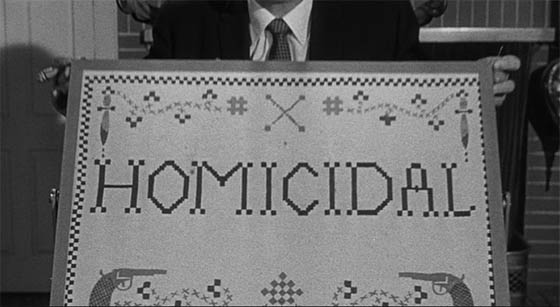

“The more adventurous among you may remember our previous excursions into the macabre. Our visits to haunted hills, to Tinglers, and to ghosts. This time we have an even stranger tale to unfold…The story of a lovable group of people who just happen to be – Homicidal.”

“The more adventurous among you may remember our previous excursions into the macabre. Our visits to haunted hills, to Tinglers, and to ghosts. This time we have an even stranger tale to unfold…The story of a lovable group of people who just happen to be – Homicidal.” Producer/director William Castle, as always, had his eyes on Hitch. His previous film,

Producer/director William Castle, as always, had his eyes on Hitch. His previous film,  The film starts with a now-requisite introduction from Castle himself; he shows off his needlework skills, pricks his finger, and looks at it with delight: “Aah – blood!” As though he just discovered it, and now he can fill his movies with it. With The Tingler (1959) and its bathtub filled with red, red blood, he’d already pushed some boundaries in this direction, but Homicidal takes Hitch’s lead and features, toward the very start of the film, a very graphic stabbing with blood pumping freely from wounds. We aren’t in 13 Ghosts anymore; hide the kids. The killing occurs completely out of the blue. In the Psycho-styled prologue, Emily (TV actress Joan Marshall, credited as “Jean Arless”), a beautiful blonde, checks into a hotel and immediately strikes up a flirtation with the bellboy. When he shows interest, she directly offers him $2000 if she’ll marry him that evening. He reluctantly agrees, and she drives him off to see a justice of the peace, waking the man in the middle of the night, and coercing him into marrying them. (His bored wife plays the “Wedding March” half-heartedly on the organ, in a nice bit of Castle humor.) After the ceremony, the justice leans forward to kiss the bride. Emily’s eyes widen in horror. She pulls out a knife and stabs the justice several times in the belly, while his wife and the bellboy watch, paralyzed with shock; then she flees. If you can’t already count off the Psycho steals in these opening scenes – Janet Leigh-ish blonde in a sleazy hotel room (with a brief glimpse of brassiere); cash which might be stolen; a brutal stabbing without warning – then you can hardly miss the one which comes next: Emily, behind the wheel, racing through the night, nervously sees police lights in the rear-view mirror. She pulls over, but the cop was actually trying to nab the driver just ahead of her. She sits on the side of the road, catches her breath, and pulls away.

The film starts with a now-requisite introduction from Castle himself; he shows off his needlework skills, pricks his finger, and looks at it with delight: “Aah – blood!” As though he just discovered it, and now he can fill his movies with it. With The Tingler (1959) and its bathtub filled with red, red blood, he’d already pushed some boundaries in this direction, but Homicidal takes Hitch’s lead and features, toward the very start of the film, a very graphic stabbing with blood pumping freely from wounds. We aren’t in 13 Ghosts anymore; hide the kids. The killing occurs completely out of the blue. In the Psycho-styled prologue, Emily (TV actress Joan Marshall, credited as “Jean Arless”), a beautiful blonde, checks into a hotel and immediately strikes up a flirtation with the bellboy. When he shows interest, she directly offers him $2000 if she’ll marry him that evening. He reluctantly agrees, and she drives him off to see a justice of the peace, waking the man in the middle of the night, and coercing him into marrying them. (His bored wife plays the “Wedding March” half-heartedly on the organ, in a nice bit of Castle humor.) After the ceremony, the justice leans forward to kiss the bride. Emily’s eyes widen in horror. She pulls out a knife and stabs the justice several times in the belly, while his wife and the bellboy watch, paralyzed with shock; then she flees. If you can’t already count off the Psycho steals in these opening scenes – Janet Leigh-ish blonde in a sleazy hotel room (with a brief glimpse of brassiere); cash which might be stolen; a brutal stabbing without warning – then you can hardly miss the one which comes next: Emily, behind the wheel, racing through the night, nervously sees police lights in the rear-view mirror. She pulls over, but the cop was actually trying to nab the driver just ahead of her. She sits on the side of the road, catches her breath, and pulls away. Of course, Marion Crane was just a petty thief, not a killer. Emily is psycho, and Castle seemingly gives the game away this early in the film; but there is more going on than meets the eye. For these opening scenes, Emily’s been using the false name of Miriam Webster (a name I cannot type without laughing) – we soon learn that the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin) is the daughter of Helga, the wheelchair-bound invalid whom Emily cares for in Solvang, California. As police begin circulating a description of the homicidal maniac on the loose, and that she’s been using the name “Miriam Webster,” Miriam and her pharmacist boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett, The Pirates of Blood River) begin to suspect Emily. Miriam’s half-brother, Warren, is dubious – but we also learn that he just secretly married Emily. Meanwhile, the mute Helga fears for her life as Emily exhibits increasingly deranged behavior – like the way she sensually strokes the little knife she keeps in her briefcase – but Helga’s frantic facial contortions fail to significantly warn those around her (apparently, everyone thinks her default expression is panic, so they pay no mind). Did I mention there’s a hefty inheritance in play as well, which either Miriam or Warren stands to win?

Of course, Marion Crane was just a petty thief, not a killer. Emily is psycho, and Castle seemingly gives the game away this early in the film; but there is more going on than meets the eye. For these opening scenes, Emily’s been using the false name of Miriam Webster (a name I cannot type without laughing) – we soon learn that the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin) is the daughter of Helga, the wheelchair-bound invalid whom Emily cares for in Solvang, California. As police begin circulating a description of the homicidal maniac on the loose, and that she’s been using the name “Miriam Webster,” Miriam and her pharmacist boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett, The Pirates of Blood River) begin to suspect Emily. Miriam’s half-brother, Warren, is dubious – but we also learn that he just secretly married Emily. Meanwhile, the mute Helga fears for her life as Emily exhibits increasingly deranged behavior – like the way she sensually strokes the little knife she keeps in her briefcase – but Helga’s frantic facial contortions fail to significantly warn those around her (apparently, everyone thinks her default expression is panic, so they pay no mind). Did I mention there’s a hefty inheritance in play as well, which either Miriam or Warren stands to win? There are twists. Oh, there are twists. As with so many of the thrillers which would follow in Psycho‘s wake, particularly in the Italian giallo films of the 60’s and 70’s, a key twist involves sexual psychology – but you can discover that for yourself. Needless to say, the impact of Homicidal‘s ultimate revelation has been diluted by the passage of time (and used by other films), but it must have been pretty jaw-dropping in 1961. To get away with his twist, Castle cheats a bit, but in doing so, you might not see it coming.

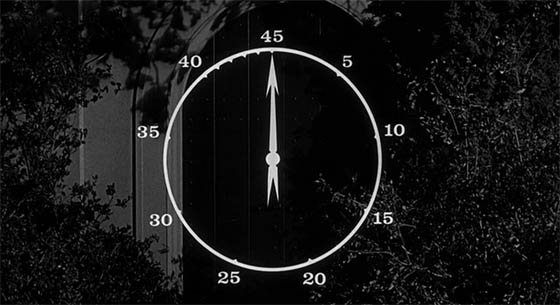

There are twists. Oh, there are twists. As with so many of the thrillers which would follow in Psycho‘s wake, particularly in the Italian giallo films of the 60’s and 70’s, a key twist involves sexual psychology – but you can discover that for yourself. Needless to say, the impact of Homicidal‘s ultimate revelation has been diluted by the passage of time (and used by other films), but it must have been pretty jaw-dropping in 1961. To get away with his twist, Castle cheats a bit, but in doing so, you might not see it coming. It was obligatory, of course, for Castle to promote the film by putting up signs stating “No One Admitted During the Last 15 Minutes of Homicidal.” He couldn’t let himself be outdone by Hitchcock. In a promotional film, he warned, “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not reveal the ending of Homicidal to your friends. Because if you do, they will kill you. And if they don’t, I will.” (Is this the first time in history a director actually threatened to murder his audience?) Of course, he needed a trademark Castle innovation/gimmick embedded in his film. This was the “Fright Break.” Just before the climax of the film (as Miriam slowly approaches a house where evil dwells), a beating heart is heard pounding on the soundtrack, and a clock is suddenly, jarringly superimposed on the screen. As it ticks down from forty-five seconds, Castle’s disembodied voice declares, “This is the Fright Break! You hear that sound? It’s the sound of a heartbeat. A frightened, terrified heart. Is it beating faster than your heart, or slower? This heart is going to beat for another twenty-five seconds to allow anyone to leave this theater who is too frightened to see the end of the picture. Ten seconds more and we go into the house. It’s now or never. Five, four – you’re a brave audience…” Should you decide to run from the theater during the Fright Break, you could receive a full refund at the Coward’s Corner, a prop built to Castle’s specifications by the management. Just stick your head out of the little window in the Coward’s Corner, right next to the words, “Nervous, tense, green with fear? Your money back, over here!” Not too many people took Castle up on this offer.

It was obligatory, of course, for Castle to promote the film by putting up signs stating “No One Admitted During the Last 15 Minutes of Homicidal.” He couldn’t let himself be outdone by Hitchcock. In a promotional film, he warned, “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not reveal the ending of Homicidal to your friends. Because if you do, they will kill you. And if they don’t, I will.” (Is this the first time in history a director actually threatened to murder his audience?) Of course, he needed a trademark Castle innovation/gimmick embedded in his film. This was the “Fright Break.” Just before the climax of the film (as Miriam slowly approaches a house where evil dwells), a beating heart is heard pounding on the soundtrack, and a clock is suddenly, jarringly superimposed on the screen. As it ticks down from forty-five seconds, Castle’s disembodied voice declares, “This is the Fright Break! You hear that sound? It’s the sound of a heartbeat. A frightened, terrified heart. Is it beating faster than your heart, or slower? This heart is going to beat for another twenty-five seconds to allow anyone to leave this theater who is too frightened to see the end of the picture. Ten seconds more and we go into the house. It’s now or never. Five, four – you’re a brave audience…” Should you decide to run from the theater during the Fright Break, you could receive a full refund at the Coward’s Corner, a prop built to Castle’s specifications by the management. Just stick your head out of the little window in the Coward’s Corner, right next to the words, “Nervous, tense, green with fear? Your money back, over here!” Not too many people took Castle up on this offer. As a theater-going event, Homicidal doubtless delivered the goods. As a film, it doesn’t hold up too well. Since the Castle gimmick comes so late in the film, and because the film’s tone has heretofore been so much more serious than The Tingler or 13 Ghosts, the Fright Break is giggle-inducing but distracting as hell. The film survives less as a psychosexual thriller and more as camp artifact, though surely it had some impact: those horror films in ensuing decades with an over-the-top, rug-pulling twist probably owe more to Homicidal than Psycho. As cinema entered the 1960’s, and the horror genre further pushed the envelope, could Castle adapt his approach? To be continued.

As a theater-going event, Homicidal doubtless delivered the goods. As a film, it doesn’t hold up too well. Since the Castle gimmick comes so late in the film, and because the film’s tone has heretofore been so much more serious than The Tingler or 13 Ghosts, the Fright Break is giggle-inducing but distracting as hell. The film survives less as a psychosexual thriller and more as camp artifact, though surely it had some impact: those horror films in ensuing decades with an over-the-top, rug-pulling twist probably owe more to Homicidal than Psycho. As cinema entered the 1960’s, and the horror genre further pushed the envelope, could Castle adapt his approach? To be continued.

“This piece of music which has gone on for some time, perhaps even since the beginning of the evening, is a kind of cyclically repeated refrain in which the same passages can always be recognized at regular intervals…” – Alain Robbe-Grillet, La Maison de Rendez-vous (1965)

“This piece of music which has gone on for some time, perhaps even since the beginning of the evening, is a kind of cyclically repeated refrain in which the same passages can always be recognized at regular intervals…” – Alain Robbe-Grillet, La Maison de Rendez-vous (1965) But to say that the film has no conventional narrative is an understatement. The film was a grand experiment. Alain Resnais had previously directed Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), which was written by an acclaimed experimental novelist, Marguerite Duras. For his follow-up, he again requested a screenplay from a pioneer of the nouveau roman: Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose novels took place in the past, present, and future simultaneously, and routinely switched tenses and from third- to first-person and back again, too fickle to settle on any single costume for the party. The two Alains presented a formidable artistic force. Robbe-Grillet had submitted a script as though it were simply another of his mind-bending psychological novels, with little concession toward traditional cinematic qualities. Resnais filmed it exactly as it was, posing his characters to his screenplay’s exact specifications, switching scenes and moods with every edit, and refusing to trim Robbe-Grillet’s trademark circular narration, which circles and circles the same phrases and imagery: “…Silent rooms, where one’s footsteps are absorbed by carpets so thick, so heavy, that no sound reaches one’s ear, as if the very ear of he who walks on once again along these corridors, through these salons and galleries in this edifice of a bygone era, this sprawling, sumptuous, baroque, gloomy hotel, where one endless corridor follows another; silent, empty corridors, heavy with cold, dark woodwork, stucco, molded paneling, marble, black mirrors, dark-toned portraits, columns, sculpted doorframes, rows of doorways, galleries, side corridors, that in turn lead to empty salons, salons heavy with ornamentation of a bygone era…”

But to say that the film has no conventional narrative is an understatement. The film was a grand experiment. Alain Resnais had previously directed Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), which was written by an acclaimed experimental novelist, Marguerite Duras. For his follow-up, he again requested a screenplay from a pioneer of the nouveau roman: Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose novels took place in the past, present, and future simultaneously, and routinely switched tenses and from third- to first-person and back again, too fickle to settle on any single costume for the party. The two Alains presented a formidable artistic force. Robbe-Grillet had submitted a script as though it were simply another of his mind-bending psychological novels, with little concession toward traditional cinematic qualities. Resnais filmed it exactly as it was, posing his characters to his screenplay’s exact specifications, switching scenes and moods with every edit, and refusing to trim Robbe-Grillet’s trademark circular narration, which circles and circles the same phrases and imagery: “…Silent rooms, where one’s footsteps are absorbed by carpets so thick, so heavy, that no sound reaches one’s ear, as if the very ear of he who walks on once again along these corridors, through these salons and galleries in this edifice of a bygone era, this sprawling, sumptuous, baroque, gloomy hotel, where one endless corridor follows another; silent, empty corridors, heavy with cold, dark woodwork, stucco, molded paneling, marble, black mirrors, dark-toned portraits, columns, sculpted doorframes, rows of doorways, galleries, side corridors, that in turn lead to empty salons, salons heavy with ornamentation of a bygone era…” If the dictum of cinema is to show-not-tell, Resnais stubbornly does both, reading off Robbe-Grillet’s cyclical prose as he depicts the winding, ever-changing hallways of the hotel, as vast and eerie as Bergman’s in The Silence (1963) or Kubrick’s in The Shining (1980). Our narrator is only called “X.” in the screenplay, and he’s played by Giorgio Albertazzi, an Italian actor in the suave, seductive mode of Marcello Mastroianni. Within the confines of an elegant and sprawling hotel, he meets a woman, “A.” (Delphine Seyrig), who is married to a tall, gaunt figure, “M.” (Sacha Pitoëff). X.’s narration is actually a monologue delivered to A., trying to convince her that they met one year ago, possibly in Frederiksbad, possibly in Marienbad, possibly somewhere else. She denies ever knowing him. He describes how he first saw her; how they discussed the statue upon the terrace and what it might be; how he took a photograph of her sitting upon a white bench; how she broke the heel of her shoe; how her husband suspected them. And she denies all of it.

If the dictum of cinema is to show-not-tell, Resnais stubbornly does both, reading off Robbe-Grillet’s cyclical prose as he depicts the winding, ever-changing hallways of the hotel, as vast and eerie as Bergman’s in The Silence (1963) or Kubrick’s in The Shining (1980). Our narrator is only called “X.” in the screenplay, and he’s played by Giorgio Albertazzi, an Italian actor in the suave, seductive mode of Marcello Mastroianni. Within the confines of an elegant and sprawling hotel, he meets a woman, “A.” (Delphine Seyrig), who is married to a tall, gaunt figure, “M.” (Sacha Pitoëff). X.’s narration is actually a monologue delivered to A., trying to convince her that they met one year ago, possibly in Frederiksbad, possibly in Marienbad, possibly somewhere else. She denies ever knowing him. He describes how he first saw her; how they discussed the statue upon the terrace and what it might be; how he took a photograph of her sitting upon a white bench; how she broke the heel of her shoe; how her husband suspected them. And she denies all of it. Resnais conveys great dislocation by playfully alternating the environment from shot to shot. There is no continuity, by design. Seyrig’s dress shifts from white to black, as do the hallways; even the painting of the hotel garden is swapped with one in negative, the whites becoming blacks and vice versa. Three different palaces were used to stand in for a single hotel; a character will stand in one corridor, turn around, and face a corridor in a completely different building. The statue itself moves around just as much as X. and A. do, at one point overlooking the gardens (facing in either direction), at another point overlooking a river or lake. Resnais staged one unnerving shot not unlike a Magritte painting, with the perfectly-still guests in the gardens casting long, slanting shadows, but the conical shrubbery around them casting none. This was achieved by painting false shadows beside the extras. For all that effort, on a first viewing you might not even notice; but it feels wrong; it feels alarming.

Resnais conveys great dislocation by playfully alternating the environment from shot to shot. There is no continuity, by design. Seyrig’s dress shifts from white to black, as do the hallways; even the painting of the hotel garden is swapped with one in negative, the whites becoming blacks and vice versa. Three different palaces were used to stand in for a single hotel; a character will stand in one corridor, turn around, and face a corridor in a completely different building. The statue itself moves around just as much as X. and A. do, at one point overlooking the gardens (facing in either direction), at another point overlooking a river or lake. Resnais staged one unnerving shot not unlike a Magritte painting, with the perfectly-still guests in the gardens casting long, slanting shadows, but the conical shrubbery around them casting none. This was achieved by painting false shadows beside the extras. For all that effort, on a first viewing you might not even notice; but it feels wrong; it feels alarming. The constant dislocation is essential to the story, because we are not in any one place – we are not in “reality” – but in the thoughts and feelings of X. and (possibly, alternately) A. He is telling her that it happened like this, or possibly like that, and she resists, imagines, denies, counter-offers, fantasizes, dreads. It’s a struggle of wills, in which his version of events battles with hers. As was psychologically in fashion, there is no “objective” truth, but only subjectivity. So this is a tale set only in competing subjective realities (I’m reminded of the science fiction novels of Philip K. Dick, in particular 1957’s Eye in the Sky).

The constant dislocation is essential to the story, because we are not in any one place – we are not in “reality” – but in the thoughts and feelings of X. and (possibly, alternately) A. He is telling her that it happened like this, or possibly like that, and she resists, imagines, denies, counter-offers, fantasizes, dreads. It’s a struggle of wills, in which his version of events battles with hers. As was psychologically in fashion, there is no “objective” truth, but only subjectivity. So this is a tale set only in competing subjective realities (I’m reminded of the science fiction novels of Philip K. Dick, in particular 1957’s Eye in the Sky).

Another possibility is that this is a haunted house tale, but told from the point of view of ghosts (one, or all of them). We even witness a potential, tragic end, when M. bursts into the bedroom occupied by A., and shoots her with a pistol. This may not have happened. It’s offered up, but the story continues, and X. talks on. Something dreadful occurred, however. That dreadful thing might simply be that she acquiesced to the seduction, and cheated on her husband. But many viewers (including my wife) see this as a story about rape. In a metaphorical sense, this must be true, since X. moves from seduction to more emphatically pressing his version of events upon the unwilling A. But there is also a moment – which happened, one year ago in one way or another – in which X. storms violently into A.’s hotel room and…what? The film does not say. Very suspiciously, X. drops a line that he did not “force” her, delivered in such a way that it reeks of guilt. Resnais films the confrontation as a fantasy sequence from X.’s P.O.V., with A.’s arms outstretched and an ecstatic smile for her lover, but the camera plunges toward her in a sudden spasm, the score shrieks loudly, the film is overexposed, bleaching white: cinematically, it is rape, and X.’s denials of force merely point the finger more emphatically toward this interpretation. Is this entire, ninety-minute monologue just X. breaking through A.’s repressed memories of a casual flirtation that led to sexual assault?

Another possibility is that this is a haunted house tale, but told from the point of view of ghosts (one, or all of them). We even witness a potential, tragic end, when M. bursts into the bedroom occupied by A., and shoots her with a pistol. This may not have happened. It’s offered up, but the story continues, and X. talks on. Something dreadful occurred, however. That dreadful thing might simply be that she acquiesced to the seduction, and cheated on her husband. But many viewers (including my wife) see this as a story about rape. In a metaphorical sense, this must be true, since X. moves from seduction to more emphatically pressing his version of events upon the unwilling A. But there is also a moment – which happened, one year ago in one way or another – in which X. storms violently into A.’s hotel room and…what? The film does not say. Very suspiciously, X. drops a line that he did not “force” her, delivered in such a way that it reeks of guilt. Resnais films the confrontation as a fantasy sequence from X.’s P.O.V., with A.’s arms outstretched and an ecstatic smile for her lover, but the camera plunges toward her in a sudden spasm, the score shrieks loudly, the film is overexposed, bleaching white: cinematically, it is rape, and X.’s denials of force merely point the finger more emphatically toward this interpretation. Is this entire, ninety-minute monologue just X. breaking through A.’s repressed memories of a casual flirtation that led to sexual assault? Yet what then does one make of the scenes which follow? A. agrees to wait for X. (this is still delivered in the past tense) and they will run off together – which happens, as she abandons her husband and steps off into the pitch-dark night. When did this happen – one year ago, or in the present? It can’t be a year ago, because we know that they parted ways (in Frederiksbad, or Marienbad): “And you asked me to give you a year, thinking perhaps to test me, or wear me down, or just forget all about me. But time doesn’t count.” So, one assumes, we are in the present, and he has at last won his argument, and persuaded A. of his reality, whether or not they really have met before (because maybe they haven’t, and this is all a con of seduction). But time doesn’t count in the fictions of Robbe-Grillet, nor in the world of Last Year at Marienbad. Neither is there any line between memory and fantasy. It’s possible for a dozen people to go see Marienbad together and walk out with a dozen different interpretations, all of them equally valid. It is not a “difficult” film, because that was supposed to happen.

Yet what then does one make of the scenes which follow? A. agrees to wait for X. (this is still delivered in the past tense) and they will run off together – which happens, as she abandons her husband and steps off into the pitch-dark night. When did this happen – one year ago, or in the present? It can’t be a year ago, because we know that they parted ways (in Frederiksbad, or Marienbad): “And you asked me to give you a year, thinking perhaps to test me, or wear me down, or just forget all about me. But time doesn’t count.” So, one assumes, we are in the present, and he has at last won his argument, and persuaded A. of his reality, whether or not they really have met before (because maybe they haven’t, and this is all a con of seduction). But time doesn’t count in the fictions of Robbe-Grillet, nor in the world of Last Year at Marienbad. Neither is there any line between memory and fantasy. It’s possible for a dozen people to go see Marienbad together and walk out with a dozen different interpretations, all of them equally valid. It is not a “difficult” film, because that was supposed to happen.