The difference is that it’s real. Every high speed spin-out, every flip, every crash. They really drive those cars over raised bridges, through billboards, backwards into rivers, off steep precipices, through fences and into trees and buildings. It would be so easy to fake now, to digitally erase the cables or to CG it entirely, but the audience would know. Just as you know, watching Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974), that this is risky, seat-of-your-pants, bona-fide.

The difference is that it’s real. Every high speed spin-out, every flip, every crash. They really drive those cars over raised bridges, through billboards, backwards into rivers, off steep precipices, through fences and into trees and buildings. It would be so easy to fake now, to digitally erase the cables or to CG it entirely, but the audience would know. Just as you know, watching Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974), that this is risky, seat-of-your-pants, bona-fide.

It was a low-budget Twentieth Century Fox drive-in movie (adapted from a novel called The Chase by Richard Unekis), and the studio surely had modest expectations. Peter Fonda was given the lead (“Larry”), an icon thanks to Easy Rider (1969) but not a major box office star; and some talent was imported from England: Susan George (Straw Dogs) was to play Mary, a free-spirited American girl; attached to direct was John Hough, who had just made The Legend of Hell House (1973), and was an unusual choice for an American action film. Everyone, including a team of drivers led by stunt coordinator Al Wyatt, attacked this little film like they had something to prove.

The plot is straightforward, uncomplicated by twists and turns, unless they take the shape of dusty California roads. What makes it special is the telling: there isn’t much exposition, but we join Larry and his partner Deke (Adam Roarke, The Losers) right before they enact the heist of a supermarket – we only realize what it is they’re doing just as they’re doing it. While Larry marches into the store manager’s office to ask for the money from the safe, Deke breaks into the manager’s home and holds his wife and child hostage. Hough enlisted his Hell House star Roddy McDowall for an uncredited cameo as the supermarket manager, and it’s ideal casting, since McDowall is the prince of manic worried looks and nervous energy. It’s fascinating to watch his acting style opposite Fonda’s in their brief scene together. In films like The Trip (1967), Spirits of the Dead (1968), and Easy Rider, Fonda was the hunky flower child; Dirty Mary marks a transition into a persona Fonda would wear through much of the 70’s, that of the cocky, laid-back good ol’ boy. He struts into McDowall’s office expecting his prey to comply with every word, but at the first sign of resistance, Fonda’s gum-chewing grin vanishes, he picks up a framed picture of the man’s family, looks at it significantly, and says, “Mind if I use your phone?” For an ostensibly fun action movie, there’s a weird, chilly undercurrent, particularly in these early scenes. We hardly know Deke, for example, but he seems at first frighteningly detached, and when he seizes McDowall’s nude wife in the shower, we fear for the woman. He impatiently assures her that rape is the furthest thing from his mind – he just wants to get the job done; and as the film progresses, we come to like Deke, and perhaps trust him considerably more than “Crazy” Larry, who, behind his Cheshire smile and Mad Hatter giggle, proves less capable of empathy.

But their characters play out on the open road, and express themselves through maneuvers and escapes across the sun-bleached California countryside. Unwillingly they pick up Mary Coombs, a young drifter that Larry slept with the night before and promptly abandoned. Stowing away in his getaway car, wearing jeans and a denim bikini top, she hides his keys from him just to get on his nerves. Larry doesn’t have time to get rid of her as he hurries to pick up Deke and tear out of San Francisco. We’re half an hour into the film and barely know a thing about Larry, Deke, or Mary, and in fact many significant character details are explained only much, much later. Instead, we get to know them through their personalities: Deke, intelligent and reserved; Larry, careless and a bit cold; Mary, taunting but easily wounded, abrasive and unpredictable. She sets the two against one another. They ditch her twice but are forced to scoop her up again. (Among Fonda’s many David Mamet-style lines is, most memorably, “Every bone in her crotch I’m gonna break.”) She couldn’t care less that they robbed a supermarket, and doesn’t ask for a share of the loot; like Larry, she gets her kicks from the adventure of it all.

But their characters play out on the open road, and express themselves through maneuvers and escapes across the sun-bleached California countryside. Unwillingly they pick up Mary Coombs, a young drifter that Larry slept with the night before and promptly abandoned. Stowing away in his getaway car, wearing jeans and a denim bikini top, she hides his keys from him just to get on his nerves. Larry doesn’t have time to get rid of her as he hurries to pick up Deke and tear out of San Francisco. We’re half an hour into the film and barely know a thing about Larry, Deke, or Mary, and in fact many significant character details are explained only much, much later. Instead, we get to know them through their personalities: Deke, intelligent and reserved; Larry, careless and a bit cold; Mary, taunting but easily wounded, abrasive and unpredictable. She sets the two against one another. They ditch her twice but are forced to scoop her up again. (Among Fonda’s many David Mamet-style lines is, most memorably, “Every bone in her crotch I’m gonna break.”) She couldn’t care less that they robbed a supermarket, and doesn’t ask for a share of the loot; like Larry, she gets her kicks from the adventure of it all.

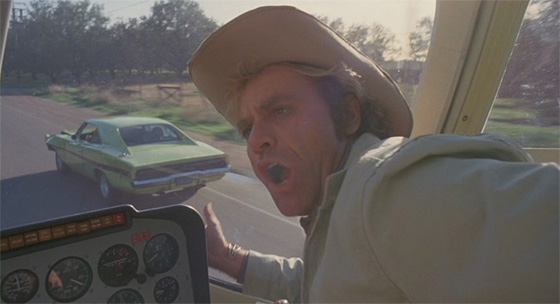

Every car chase movie requires a pursuer, a chief antagonist, and here it’s Vic Morrow playing Franklin, a police captain who refuses to wear a gun or a badge. He’s quite natural in the requisite, and labored, police station cutaways, as the film hammers home that he’s a tough-as-nails loose cannon, et cetera, et cetera. Once he gets off the CB and starts giving chase in a helicopter, Morrow is spectacular, ignoring his pilot’s warnings that they’re short on fuel, urging him to fly lower and lower until they’re swooping between rows of trees and ramming the roof of Fonda’s Dodge Charger.

Every car chase movie requires a pursuer, a chief antagonist, and here it’s Vic Morrow playing Franklin, a police captain who refuses to wear a gun or a badge. He’s quite natural in the requisite, and labored, police station cutaways, as the film hammers home that he’s a tough-as-nails loose cannon, et cetera, et cetera. Once he gets off the CB and starts giving chase in a helicopter, Morrow is spectacular, ignoring his pilot’s warnings that they’re short on fuel, urging him to fly lower and lower until they’re swooping between rows of trees and ramming the roof of Fonda’s Dodge Charger.

Watching this scene, as with so many of the film’s stunt sequences, is downright nerve-wracking. They really did fly a helicopter that close to the car, aiming its chopping blades mere feet from the Charger as it lunges forward, hovering above to rap its runners against the top of the car, gliding beside it so Morrow, in the helicopter, can be seen delivering his dialogue over the CB directly to Fonda, in the Charger. Hough and his stunt team were fearless. So were his actors. We frequently see Fonda at the wheel and George and Roarke beside him while he drives high-speed with the police in pursuit. We’re in the helicopter with Morrow, too, and it’s hard not to think that his life would end this way, tragically and pointlessly, when a helicopter and its spinning blades broke free above him and toppled, on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). There’s no connection, there’s no irony – but nevertheless it’s hard to free that thought from your mind. And still you have to admit to yourself that it’s thrilling to watch the actors and crew risk their lives to pull off these shots.

Watching this scene, as with so many of the film’s stunt sequences, is downright nerve-wracking. They really did fly a helicopter that close to the car, aiming its chopping blades mere feet from the Charger as it lunges forward, hovering above to rap its runners against the top of the car, gliding beside it so Morrow, in the helicopter, can be seen delivering his dialogue over the CB directly to Fonda, in the Charger. Hough and his stunt team were fearless. So were his actors. We frequently see Fonda at the wheel and George and Roarke beside him while he drives high-speed with the police in pursuit. We’re in the helicopter with Morrow, too, and it’s hard not to think that his life would end this way, tragically and pointlessly, when a helicopter and its spinning blades broke free above him and toppled, on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). There’s no connection, there’s no irony – but nevertheless it’s hard to free that thought from your mind. And still you have to admit to yourself that it’s thrilling to watch the actors and crew risk their lives to pull off these shots.

Stuntwork aside, there’s an organic connection to how everything else in this film is shot. Hough rode in the car with his actors. Usually they didn’t rehearse their lines, and much of the dialogue is improvised. They were on the road, making a movie for all the hours that they had daylight, grabbing all the shots they could. The result is not just what you see but what you feel: that nothing is faked, that you’re on the trip and part of the getaway. Like Easy Rider, as well as the films to which it’s typically compared, Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Vanishing Point (1971), you are on an authentic American road trip. That a British director could make such a quintessentially American film is an achievement; and though it ends on a cynical and downbeat (and utterly ridiculous) note, what you remember, and the reason you’ll go back to it, is that sense of liberation, of defying the speed limit and bearing for the hills; the way that Peter Fonda frets when he’s still and apart from the wheel, but grins whenever a police car appears in the rear-view mirror – with a sense of purpose.

Stuntwork aside, there’s an organic connection to how everything else in this film is shot. Hough rode in the car with his actors. Usually they didn’t rehearse their lines, and much of the dialogue is improvised. They were on the road, making a movie for all the hours that they had daylight, grabbing all the shots they could. The result is not just what you see but what you feel: that nothing is faked, that you’re on the trip and part of the getaway. Like Easy Rider, as well as the films to which it’s typically compared, Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Vanishing Point (1971), you are on an authentic American road trip. That a British director could make such a quintessentially American film is an achievement; and though it ends on a cynical and downbeat (and utterly ridiculous) note, what you remember, and the reason you’ll go back to it, is that sense of liberation, of defying the speed limit and bearing for the hills; the way that Peter Fonda frets when he’s still and apart from the wheel, but grins whenever a police car appears in the rear-view mirror – with a sense of purpose.

The film grossed its budget fifteen times over, and Fonda, who was entitled to a certain percentage, became a wealthy man. It’s now available from Shout! Factory on a 2-DVD set with another Peter Fonda vehicle, Race with the Devil (1975). You can purchase it through Amazon here:

Dirty Mary Crazy Larry / Race With The Devil

There is a single brief shot in Allan Arkush’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979) which qualifies it as one of the greatest rock movies ever made. A happy accident, as it turns out. The camera was running at the wrong speed. The crew had been filming a day-long performance by The Ramones for the film’s centerpiece concert scene. What had, at first, been a raucous concert for an elated gathering of extras gradually turned sour as the band replayed the same songs, over and over, as Arkush worked to get every necessary shot for the extended sequence before the extras fled; and those extras came very close to mutiny as the hours passed in the hot and cramped Roxy Theatre in West Hollywood. Arkush claims the filming stretched to 22 hours “at roughly 130 decibels.” You can have too much of a good thing, it seems. At one point an undercranked camera captured leads P.J. Soles and Dey Young in the crowd. Soles, playing Ramones super-fan Riff Randell, clutches in a fist the lyrics to a song she hopes to deliver to the band after the show, and jumps frantically in place. Nerdy Dey Young, as Kate Rambeau, in a thin white top and wearing a yellow cape with black polka-dots, shyly acknowledges Soles, tries to listen attentively to the band’s music, nods her head, almost falls over as her friend slams into her, and gradually gives herself over to having fun – all of this presented, accidentally, at a hyperspeed usually associated with Keystone Cops chases. And you watch it with recognition: Oh yeah; this is what going to a concert is like. Concert movies don’t usually get across this feeling – of being an ecstatic teenager in the crowd, giving yourself over, having the time of your life with your best friend.

There is a single brief shot in Allan Arkush’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979) which qualifies it as one of the greatest rock movies ever made. A happy accident, as it turns out. The camera was running at the wrong speed. The crew had been filming a day-long performance by The Ramones for the film’s centerpiece concert scene. What had, at first, been a raucous concert for an elated gathering of extras gradually turned sour as the band replayed the same songs, over and over, as Arkush worked to get every necessary shot for the extended sequence before the extras fled; and those extras came very close to mutiny as the hours passed in the hot and cramped Roxy Theatre in West Hollywood. Arkush claims the filming stretched to 22 hours “at roughly 130 decibels.” You can have too much of a good thing, it seems. At one point an undercranked camera captured leads P.J. Soles and Dey Young in the crowd. Soles, playing Ramones super-fan Riff Randell, clutches in a fist the lyrics to a song she hopes to deliver to the band after the show, and jumps frantically in place. Nerdy Dey Young, as Kate Rambeau, in a thin white top and wearing a yellow cape with black polka-dots, shyly acknowledges Soles, tries to listen attentively to the band’s music, nods her head, almost falls over as her friend slams into her, and gradually gives herself over to having fun – all of this presented, accidentally, at a hyperspeed usually associated with Keystone Cops chases. And you watch it with recognition: Oh yeah; this is what going to a concert is like. Concert movies don’t usually get across this feeling – of being an ecstatic teenager in the crowd, giving yourself over, having the time of your life with your best friend. The marathon performance is captured as a long medley in the film (and on the LP soundtrack), interrupted for only brief bits of unimportant plot business, though even those are funny and rather energetically staged. The Ramones begin with the signature “Blitzkrieg Bop.” Kate Rambeau looks spaced-out and confused, Riff Randell in heaven. In the crowd we see their high school teacher Mr. McGree (Paul Bartel, director of Death Race 2000), who inexplicably accepted Randell’s invite to the show, instantly become a rock ‘n’ roll convert as he dances manically with a giant mutated rat.* Just your typical eclectic Ramones crowd.

The marathon performance is captured as a long medley in the film (and on the LP soundtrack), interrupted for only brief bits of unimportant plot business, though even those are funny and rather energetically staged. The Ramones begin with the signature “Blitzkrieg Bop.” Kate Rambeau looks spaced-out and confused, Riff Randell in heaven. In the crowd we see their high school teacher Mr. McGree (Paul Bartel, director of Death Race 2000), who inexplicably accepted Randell’s invite to the show, instantly become a rock ‘n’ roll convert as he dances manically with a giant mutated rat.* Just your typical eclectic Ramones crowd. As the band launches into “Teenage Lobotomy,” the words LOBOTOMY flash on the screen, becoming larger and larger, until the screen cannot encompass them; then the lyrics are subtitled like a bouncing-ball sing-along. Arkush uses the faster tempo to match the speeded-up footage of his young actresses. It may have been madness to keep the extras prisoner for this long, long shoot – most directors would quickly gather the crowd footage they need, and pick up the rest of the shots after the throng disperses – but the advantage to Arkush’s decision is that there is no invisible line between the Ramones and their audience. Joey Ramone plunges constantly toward the mob, pointing at them, beckoning them with his oversized hands; the camera swings back and forth, films from behind them and from every conceivable angle. It’s convincing because it’s all live and improvised; but the technique also gives the whole long scene a sweaty, tactile, and unpredictable energy.

As the band launches into “Teenage Lobotomy,” the words LOBOTOMY flash on the screen, becoming larger and larger, until the screen cannot encompass them; then the lyrics are subtitled like a bouncing-ball sing-along. Arkush uses the faster tempo to match the speeded-up footage of his young actresses. It may have been madness to keep the extras prisoner for this long, long shoot – most directors would quickly gather the crowd footage they need, and pick up the rest of the shots after the throng disperses – but the advantage to Arkush’s decision is that there is no invisible line between the Ramones and their audience. Joey Ramone plunges constantly toward the mob, pointing at them, beckoning them with his oversized hands; the camera swings back and forth, films from behind them and from every conceivable angle. It’s convincing because it’s all live and improvised; but the technique also gives the whole long scene a sweaty, tactile, and unpredictable energy. The song “Pinhead” captures Joey with a fisheye lens, and honestly, dear, sweet, chinless Joey is already a somewhat Lovecraftian creature, so the fisheye – as he stares with a single bulging eye visible through tinted glasses, leering toward the camera – is pretty damn creepy. As the Ramones sing “D-U-M-B” twice, Arkush first spells the words correctly at the bottom of the screen, then incorrectly (D-M-U-B). Zippy the Pinhead walks onstage with a “Gabba-Gabba-Hey” sign. Magically, everyone in the crowd now has “Gabba-Gabba-Hey” signs. Zippy would soon become a recurring character in the Ramones’ act (just one of the many ways that the Ramones embraced the film and the fans they gained because of it).

The song “Pinhead” captures Joey with a fisheye lens, and honestly, dear, sweet, chinless Joey is already a somewhat Lovecraftian creature, so the fisheye – as he stares with a single bulging eye visible through tinted glasses, leering toward the camera – is pretty damn creepy. As the Ramones sing “D-U-M-B” twice, Arkush first spells the words correctly at the bottom of the screen, then incorrectly (D-M-U-B). Zippy the Pinhead walks onstage with a “Gabba-Gabba-Hey” sign. Magically, everyone in the crowd now has “Gabba-Gabba-Hey” signs. Zippy would soon become a recurring character in the Ramones’ act (just one of the many ways that the Ramones embraced the film and the fans they gained because of it).

[In this new series, which will be categorized in the menu at left as LATE NIGHT TV, I’ll be looking at select episodes of either acclaimed or overlooked cult television series.]

[In this new series, which will be categorized in the menu at left as LATE NIGHT TV, I’ll be looking at select episodes of either acclaimed or overlooked cult television series.] I’m a fan of Cushing, but have always particularly relished his portrayal of Holmes in 1958’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, made for Hammer Films. All right, his performance may have been just a bit too mannered, but he looked every bit the Strand illustrations of Holmes. It was perfect casting for a wonderful actor. That film remains one of my favorite Holmes adaptations – I’m a sucker, too, for the lush color and the token Hammer touches of blood and chills – but I didn’t know what to think when I saw that the first two episodes on the A&E set were a two-part adaptation of Doyle’s “Hound.” Cushing, doing “Hound”, again? On a BBC budget? I’d be forced to compare/contrast, though I was a tad reluctant. I wanted to see Cushing tackle the rest of the Holmes canon…alas, this and four other Holmes mysteries are the only surviving episodes of the sixteen-episode television series (properly titled Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes). So I’ll take what I can get.

I’m a fan of Cushing, but have always particularly relished his portrayal of Holmes in 1958’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, made for Hammer Films. All right, his performance may have been just a bit too mannered, but he looked every bit the Strand illustrations of Holmes. It was perfect casting for a wonderful actor. That film remains one of my favorite Holmes adaptations – I’m a sucker, too, for the lush color and the token Hammer touches of blood and chills – but I didn’t know what to think when I saw that the first two episodes on the A&E set were a two-part adaptation of Doyle’s “Hound.” Cushing, doing “Hound”, again? On a BBC budget? I’d be forced to compare/contrast, though I was a tad reluctant. I wanted to see Cushing tackle the rest of the Holmes canon…alas, this and four other Holmes mysteries are the only surviving episodes of the sixteen-episode television series (properly titled Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes). So I’ll take what I can get. To parrot the tired old factoid, Sherlock Holmes has appeared in more films than any other fictional character, and “The Hound of the Baskervilles” has always been one of the most popular stories to adapt. It’s easy to see why, since the idea of Holmes facing off against a monster (of sorts) is an appealing one. But it also presents two very large problems. For one thing, when the titular hound finally appears, it’s a challenge to make it look like more than just a big old dog (and who doesn’t love dogs?). More critically, Holmes is only present for the beginning and ending of the story, with Watson left as the detective for the long stretch in-between. Now, if you’re reading the stories, neither of these presents much of a problem. To the first point: you have your imagination, and the dog can be as fearsome as you want it to be. To the second – if you’re reading the stories chronologically, it’s actually refreshing to see Watson as detective, and a bit nerve-wracking to see him do his level best without Holmes to guide him.

To parrot the tired old factoid, Sherlock Holmes has appeared in more films than any other fictional character, and “The Hound of the Baskervilles” has always been one of the most popular stories to adapt. It’s easy to see why, since the idea of Holmes facing off against a monster (of sorts) is an appealing one. But it also presents two very large problems. For one thing, when the titular hound finally appears, it’s a challenge to make it look like more than just a big old dog (and who doesn’t love dogs?). More critically, Holmes is only present for the beginning and ending of the story, with Watson left as the detective for the long stretch in-between. Now, if you’re reading the stories, neither of these presents much of a problem. To the first point: you have your imagination, and the dog can be as fearsome as you want it to be. To the second – if you’re reading the stories chronologically, it’s actually refreshing to see Watson as detective, and a bit nerve-wracking to see him do his level best without Holmes to guide him. I suppose that’s part of the reason I was disappointed to see “Hound of the Baskervilles” as the first Holmes mystery in the set. I was a Cushing fan, and I wanted to see Cushing; I didn’t want him to drop out of the bulk of his own adventure…again. But this was not actually the first of the episodes to air (that would be “The Second Stain,” which is one of the lost episodes); and, in fact, I learn from

I suppose that’s part of the reason I was disappointed to see “Hound of the Baskervilles” as the first Holmes mystery in the set. I was a Cushing fan, and I wanted to see Cushing; I didn’t want him to drop out of the bulk of his own adventure…again. But this was not actually the first of the episodes to air (that would be “The Second Stain,” which is one of the lost episodes); and, in fact, I learn from  It is more faithful, and though with both episodes together the story runs only slightly longer than the 1958 Terence Fisher film, it does touch on more plot details from Doyle’s tale, and dispenses with the Hammer-isms (Sherlock doesn’t have to battle a tarantula, for example). Cushing, a decade older and slightly more gaunt, gives a very different performance. His Holmes is less kinetic, though still engaged; there’s a touch of world-weariness to him. He’s very good in the final scenes, when he suddenly realizes he’s made a grave mistake in his plans: he hasn’t taken the English fog into account, which threatens to foil everything. (My wife and I were both reminded of the 2010 Stephen Moffat series Sherlock, in which Holmes is ignorant that the Earth revolves around the Sun, because that information is useless to his work.) He’s also excellent at declaring “the game is afoot” as he charges out of the tavern; this, for an actor, must be like delivering “to be or not to be” while trying to sound spontaneous.

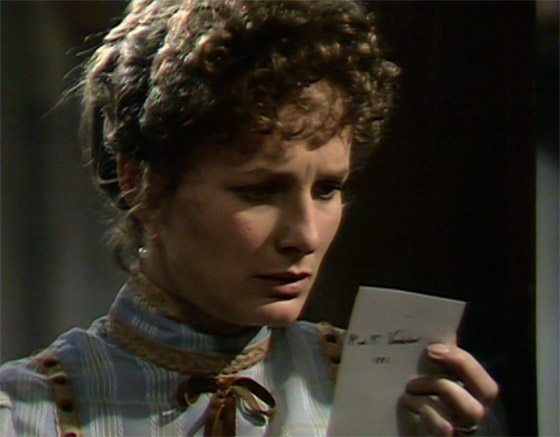

It is more faithful, and though with both episodes together the story runs only slightly longer than the 1958 Terence Fisher film, it does touch on more plot details from Doyle’s tale, and dispenses with the Hammer-isms (Sherlock doesn’t have to battle a tarantula, for example). Cushing, a decade older and slightly more gaunt, gives a very different performance. His Holmes is less kinetic, though still engaged; there’s a touch of world-weariness to him. He’s very good in the final scenes, when he suddenly realizes he’s made a grave mistake in his plans: he hasn’t taken the English fog into account, which threatens to foil everything. (My wife and I were both reminded of the 2010 Stephen Moffat series Sherlock, in which Holmes is ignorant that the Earth revolves around the Sun, because that information is useless to his work.) He’s also excellent at declaring “the game is afoot” as he charges out of the tavern; this, for an actor, must be like delivering “to be or not to be” while trying to sound spontaneous. Still, this is “Hound of the Baskervilles,” and so you don’t get a lot of Sherlock Holmes. It’s Watson’s show, and Watson here is Nigel Stock (not to be confused with Nigel Bruce, the most famous Watson of all, from the long-running film series with Basil Rathbone). For an extraordinary time I was gnawing at my own fist trying to remember how I knew Nigel Stock, until I realized that he was in The Prisoner, subtituting for Patrick McGoohan, thanks to body-swapping, in the episode “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling.” It’s the one episode I really, really wish hadn’t been made, since every minute of that program seems to violate the premise and themes of the series. But never mind. After a while I managed to stop holding that against Stock’s performance as Watson – which would really be unfair, don’t you think? – and came to the conclusion that he’s perfectly fine in the role. Crucially, he doesn’t portray Watson as a bumbling fool, which the character never was in Doyle’s hands. Ultimately, I prefer André Morrell from the Terence Fisher version, but I could believe Stock as Watson, and that’s what matters.

Still, this is “Hound of the Baskervilles,” and so you don’t get a lot of Sherlock Holmes. It’s Watson’s show, and Watson here is Nigel Stock (not to be confused with Nigel Bruce, the most famous Watson of all, from the long-running film series with Basil Rathbone). For an extraordinary time I was gnawing at my own fist trying to remember how I knew Nigel Stock, until I realized that he was in The Prisoner, subtituting for Patrick McGoohan, thanks to body-swapping, in the episode “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling.” It’s the one episode I really, really wish hadn’t been made, since every minute of that program seems to violate the premise and themes of the series. But never mind. After a while I managed to stop holding that against Stock’s performance as Watson – which would really be unfair, don’t you think? – and came to the conclusion that he’s perfectly fine in the role. Crucially, he doesn’t portray Watson as a bumbling fool, which the character never was in Doyle’s hands. Ultimately, I prefer André Morrell from the Terence Fisher version, but I could believe Stock as Watson, and that’s what matters. Neil Gaiman once said, when describing why his Neverwhere BBC series looked the way it did, “The BBC, at least at the time, had kind of a sausage mentality. It didn’t really matter what you put in at one end, you got Doctor Who out.” He was referring to the old Doctor Who of course, not the highly-polished new series (for which he’s written); but that sausage-making syndrome is exactly what you get with Sherlock Holmes. The outdoor scenes are grainy and somewhat clumsily handled; the indoor scenes are on obvious sets, with on-the-fly directing, no retakes, and sometimes muffled sound. It might as well be live television from the early 50’s. The Hound itself looks like…a cuddly dog who knows how to roll over and play dead when the director asks. And when I said these two programs were faithful to Doyle’s tale, I should have said: There is a lot of dialogue. Hammer’s version, for all its changes, made the story cinematic. This rendering is for armchair viewing only, with long stretches in which the characters simply recite facts at one another, and go over the clues or drop them. It’s charming. With nothing stylistically notable, you lower your expectations fast as the first episode begins, and then take pleasures from the story itself, with a smile at the occasional improvised flourish by an actor. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle comes to the forefront; and the story is a classic. Despite the klutziness, there’s plenty here to enjoy, in other words.

Neil Gaiman once said, when describing why his Neverwhere BBC series looked the way it did, “The BBC, at least at the time, had kind of a sausage mentality. It didn’t really matter what you put in at one end, you got Doctor Who out.” He was referring to the old Doctor Who of course, not the highly-polished new series (for which he’s written); but that sausage-making syndrome is exactly what you get with Sherlock Holmes. The outdoor scenes are grainy and somewhat clumsily handled; the indoor scenes are on obvious sets, with on-the-fly directing, no retakes, and sometimes muffled sound. It might as well be live television from the early 50’s. The Hound itself looks like…a cuddly dog who knows how to roll over and play dead when the director asks. And when I said these two programs were faithful to Doyle’s tale, I should have said: There is a lot of dialogue. Hammer’s version, for all its changes, made the story cinematic. This rendering is for armchair viewing only, with long stretches in which the characters simply recite facts at one another, and go over the clues or drop them. It’s charming. With nothing stylistically notable, you lower your expectations fast as the first episode begins, and then take pleasures from the story itself, with a smile at the occasional improvised flourish by an actor. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle comes to the forefront; and the story is a classic. Despite the klutziness, there’s plenty here to enjoy, in other words. As for Peter Cushing, he had a few more years to give to the likes of Hammer and Amicus before he began a gradual withdrawal from acting following his wife’s death in the early 70’s. He’s still best known for his role in Star Wars and as Hammer’s Dr. Frankenstein, but I’d always seen the one-off 1958 Hound of the Baskervilles as a missed opportunity – what should have been the launch of a Hammer Holmes series. The A&E set, in compiling the surviving BBC episodes, is most valuable in allowing everyone a prolonged look at Cushing as Holmes – one of the best Holmes there ever was.

As for Peter Cushing, he had a few more years to give to the likes of Hammer and Amicus before he began a gradual withdrawal from acting following his wife’s death in the early 70’s. He’s still best known for his role in Star Wars and as Hammer’s Dr. Frankenstein, but I’d always seen the one-off 1958 Hound of the Baskervilles as a missed opportunity – what should have been the launch of a Hammer Holmes series. The A&E set, in compiling the surviving BBC episodes, is most valuable in allowing everyone a prolonged look at Cushing as Holmes – one of the best Holmes there ever was.