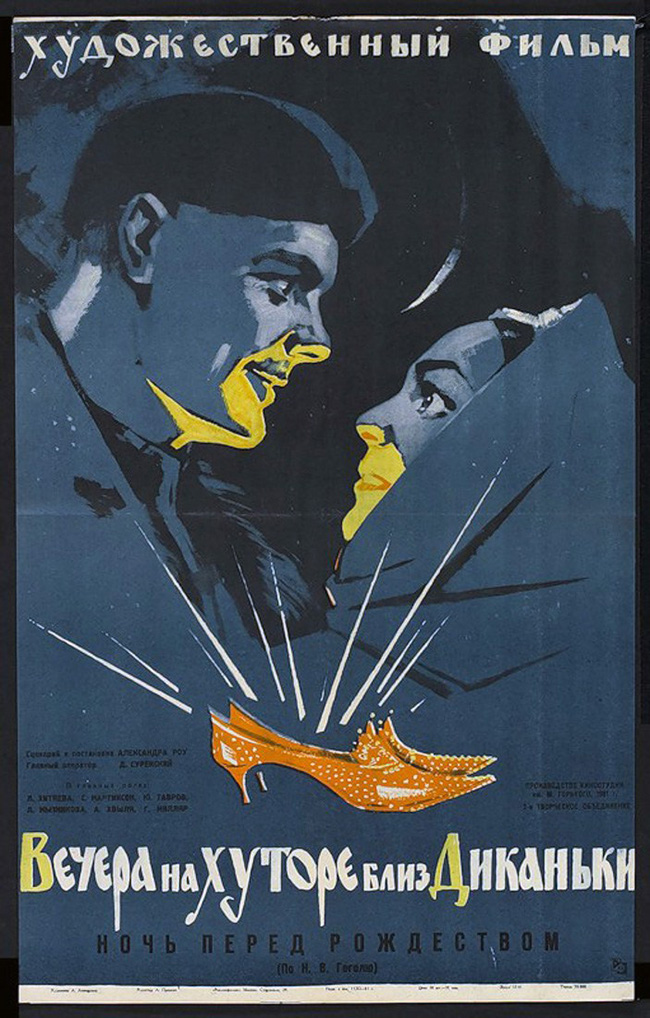

The last Russian fairy tale film we’ll be visiting this year is one of the better (but stranger) films of Aleksandr Rou, the prolific director most closely associated with the genre. Rou’s central achievement in his career was visualizing the more fantastic elements of folklore within natural environments, and with earthy characters and rustic authenticity, notably in his early films Wish Upon a Pike (1938), with its protagonist snagging a wish-granting fish portrayed by a real, smelly-looking pike, and the excellent Vasilisa the Beautiful (1939), which incorporated sets like storybook illustrations, but populated its cast with authentic country types. Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka: The Night Before Christmas (aka The Night Before Christmas, 1961), from Gorky Studios, has nothing to do with Santa or the famous poem – no visions of dancing sugar plums here. It’s based instead on a tale (“Christmas Eve”) found in a collection of connected short stories by the famous Russian author Nikolai Gogol, Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, inspired by Ukrainian folklore. (Gogol also wrote the story “Viy,” which became the 1967 film of the same name, considered to be the first Russian horror movie.) Rou finds a good match with Gogol, as both Gogol’s stories and Rou’s craft explore older traditions and a charmingly narrow view of the world, where a small village can contain a world, and to leave its boundaries is to embark on an epic adventure.

Rou favorite Georgy Millyar as a pig-snouted devil.

The film begins in a most intimidating fashion, introducing – with animated caricatures – a breathless list of twelve different characters (you will meet even more). Most of the cast, however, is inessential, and the plot eventually reveals itself to be a very basic fairy tale. Young Oksana (Lyudmyla Myznikova) is pretty but vain, and torments her suitor, the blacksmith Vakula (Yuri Tavrov), by flirting with other men when all the young folks go out to play and sled in the snow. Though he has been courting her for a while, she says she will only marry him if he brings back the Tsarina’s slippers from St. Petersburg. Meanwhile, a Devil (Georgy Millyar, who frequently cross-dresses as Baba Yaga in Rou’s films), covered in fur and with a monkey’s tail and a pig’s snout, torments the local villagers by stealing the Moon and producing a blizzard. His consort is the local matriarch and secret witch Solokha (Lyudmyla Khityayeva), Vakula’s mother. In an extended bit of mild sex farce, she’s visited over the course of Christmas Eve by a number of different men eager for her affections – beginning with the Devil – and each is compelled to hide in a sack as the next arrives. When Vakula walks in, he sees all the sacks lying about and lifts them over his shoulder to clean the house for Christmas. After an argument with Vakula, he storms out of the village taking only one sack with him – the one containing the Devil. (The others, left behind in the snow, reach their own comic ends.) After a visit with a country sorcerer (Mykola Yakovchenko) who primarily uses his magic to eat dumplings without his hands, Vakula discovers the Devil in his sack, quickly tricks him and places him under his command. On his back he flies to St. Petersburg and into the palace of the Tsar, where he charms the slippers off the Tsarina. Back in the village, rumors are spread that he’s either hanged or drowned himself (no one can decide between the two). Oksana is distraught and remorseful, but when Vakula reappears with the jeweled slippers, she covers them up and tells him that the slippers aren’t important; she’ll marry him.

Russian Christmas carolers.

Some of the sights in Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka include Solokha flying on a broom over the village and collecting the stars by hand, like something out of a Méliès film; the Devil swimming through the sky with a backstroke before burning his hands on the Moon; and Vakula, having bent the Devil to his will, riding on his back to St. Petersburg, his face lit with a blue glow while framed by the night sky, the Devil’s eyes glimmering above his snout. Reverse photography, perhaps the most frequently used tool in Rou’s belt, is deployed to the point of excess: the Devil tumbles down a hill, then back up, then down again; dumplings flying into the sorcerer’s mouth, etc. Presumably this is to keep the children in the audience entertained (Rou’s films became a staple on Russian TV as children’s programming). Notably, there is one brief scene early in the film, a flashback involving Vakula and the Devil, which is fully animated and in the style of a Fleischer cartoon. Neither Father Christmas nor Jack Frost make an appearance, somewhat disappointingly, but there is a fascinating glimpse into a Christmas tradition involving carolers receiving candy, baked goods, and meats in payment for their caroling (my wife, during this scene: “I think that person just got a whole turkey”); it’s trick ‘r’ treating Christmas style. Overall, Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka can be clumsy, goofy, or downright bizarre, but at its best it feels invaluable as a window into 19th century life in the Ukraine, with the religious and supernatural thriving alongside mundane reality and everyday problems of frustrated romance and cheating husbands.