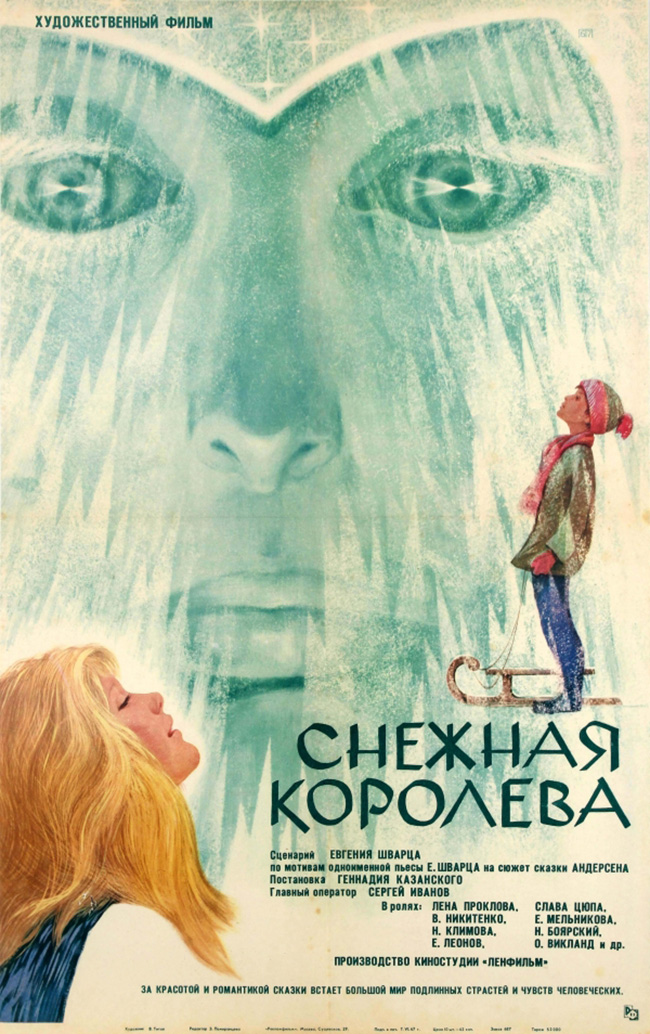

I have recently been working my way through a pile of DVDs of Russian fantasy films – not reviewing them all here, but if you’re a regular reader of this site you know the Russian fairy tale genre is something I’ve been championing for a few years (in particular the masterworks of Aleksandr Ptushko). But to come across an unexpectedly wondrous little film like Gennadiy Kazanskiy’s The Snow Queen (1966) has rejuvenated my enthusiasm for what Soviet-era cinema has to offer in fantasy storytelling. I can confidently tell you that you’ve never seen a film that looks or feels like The Snow Queen before, although its giddy appropriation of different special effects styles and animation may bring to mind the Czech fantasies of Karel Zeman, and some of its imagery might remind you of classic Walt Disney. Certain passages align closely with Aleksandr Rou’s long series of Russian fairy tale films, but the storytelling and characterizations are more sophisticated. This is because Kazanskiy’s film is based not on Russian folklore, but on Hans Christian Andersen’s melancholy tale “The Snow Queen.” Andersen is even a character, introducing the story and then diving in to participate. Kazanskiy, who was coming off a major hit in his home country with the science fiction fable Amphibian Man (1962), and who had directed the Arabian Nights fantasy Old Khottabych (released in the U.S. as The Flying Carpet, 1956), treats Andersen’s story as fairy tale spectacle, packing each scene with imaginative ideas without ever risking boredom in his young audience.

Natalya Klimova, as the Snow Queen, spies through the window.

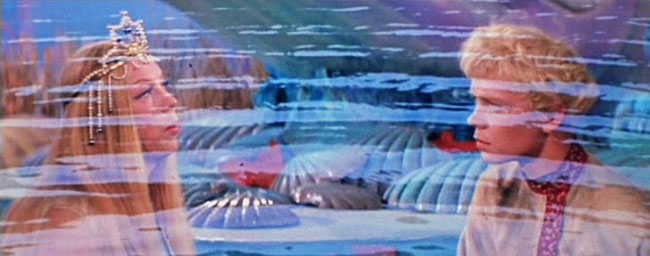

Andersen (Valeri Nikitenko) tells the story of a brother and sister, Kay (Slava Ziupa) and Gerda (Elena Proklova), who are visited one day by a pallid and gaunt ice salesman (Nikolai Boyarskiy) who wishes to purchase their grandmother’s red roses in hopes to cultivate and sell them during the winter. She treasures the roses and refuses, and in revenge the man, who is actually the servant of the magical Snow Queen (Natalya Klimova) in the distant North, summons her to punish the family. She kisses Kay and turns his heart to ice – he becomes cruel and follows her on her sleigh to her palace. Gerda runs away to search for him, occasionally assisted by Andersen himself. Along the way she meets a talking, bespectacled crow; a king who steps out of a painting in his castle and tries to trick Gerda into becoming his prisoner using magic flying skis; a party of forest bandits under a banner of skull and crossbones, popping out of doors hidden in trees, and led by a bandit queen and her clever daughter; a helpful reindeer who carries Gerda to the North; and finally the Snow Queen herself. Gerda discovers her brother drained of color and trying to spell “Eternity” with little ice cubes at the Queen’s command (he looks a bit like David Bowie’s Pierrot in the “Ashes to Ashes” video). Gerda restores his humanity and defies the Snow Queen’s stormy fury.

Gerda (Elena Proklova) searches for her brother with the assistance of a crow.

The depth of the characters and even the deployment of comedy receive more consideration than you would typically find in the straightforward genre of Russian fairy tale cinema. Consider the bandit queen’s daughter (Era Ziganshina), who saves Gerda from the clutches of the Snow Queen’s counselor but only because she wants to claim Gerda for herself: a friend is a thing as valuable as the rest of her mountain of loot which she shows off proudly. She quickly deprives Gerda of her belongings, claiming that friends share, and pulls a pistol on Gerda to let her know that the sharing is a one-way transaction. Only when Gerda – with a little help from H.C. Andersen – explains that her brother will freeze to death in the Snow Queen’s clutches does she win the girl’s sympathy. She gives Gerda back her belongings and allows her to continue her quest on the condition that Andersen tell her a story. He relates Gerda’s own tale – a story of the story we’re already watching, in a mildly meta twist – and her eyes moisten. This thawing of her heart is echoed in the eventual literal thawing of Kay by Gerda’s telling him stories of what he’s missed at home while he’s been away. Stories, and their ability to move us, conquer all. (Earlier in the film, the King must also receive a special appeal before he can be won over; it is the prince and princess who make the necessary impact. The King wants to capture Gerda to please the Snow Queen’s counselor, because otherwise the man might stop delivering his precious ice cream.)

Gerda encounters cel-animated guards at the Snow Queen’s palace.

Visually, the film is superb. The Snow Queen is a giant accompanied by a whirlwind of animated snow. Commenting on the action are a tiny gnome and a living inkwell (an actress in costume), seamlessly swapped out with a model when the gnome lifts off her head by a hinge and dips a pen down her neck to get ink for his message. The talking crow is a mechanical puppet that even walks, leading Gerda to his cottage in a meadow. The King’s castle is haunted by cel-animated ladies in waiting and weightlifting strongmen projected on the walls and over Gerda’s Red Riding Hood cape. When she steals the King’s magic skis, she flies overhead in them. In riding the reindeer to the Snow Queen’s realm, both become animated figures running over the snow toward an impressionistic painting of the Aurora Borealis – as though it is perfectly ordinary for any fantasy film to switch suddenly into a cartoon. And I doubt any children watching would flinch at the transition. The Snow Queen’s palace is guarded by more animated figures who collapse into piles of snow and ice when Gerda defies them, and the palace itself, as she advances, is a procession of paintings, miniatures, minerals and crystals. Her throne room is a vast plain of black ice which dwarfs its inhabitants, Gerda and Kay – it looks like a tableau straight out of Powell and Pressburger’s Tales of Hoffman (1951) or something by William Cameron Menzies. While Kay tries to spell “Eternity” with his ice cubes, he’s lost in a vast, abstract production design, trapped inside his own mind. But the physical/metaphysical, live action/animated, shape-shifting world of The Snow Queen is also an accomplished simulation of a child’s rich imagination.