Even in its near-complete 2010 restoration and running 150 minutes, Fritz Lang’s Silent epic Metropolis (1927) is possessed of churning, frenetic energy, like an industrial works geared to explode. It is a machine; a machine movie about other machines. And it’s running efficiently at the outset, a bright and sparkling city of skyscrapers, automobile skyways, neon signs and low-flying private planes dwarfed by the “New Tower of Babel,” all of it the construction of Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel, Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler). Only when the Eternal Gardens, a sanctuary for the privileged, is invaded by a poor girl named Maria (Brigitte Helm, L’argent), escorting a flock of dirt-smudged children into the sacred grounds to prove a point (“Look! These are your brothers!”), does the machine begin to malfunction and set a course for self-destruction. Transfixed by Maria is Fredersen’s son Freder (Gustav Fröhlich, Asphalt), who follows her into the industrial world beneath Metropolis where grim laborers endure 10-hour workdays of grueling physical hardship within colossal machines. Freder nobly trades places with one of these unfortunates and learns that Maria has been organizing the workers and preaching to them – for the audience she recounts the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel. Meanwhile, Fredersen visits Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Lang’s Dr. Mabuse), who is nearing completion of a “Machine-Man” in his laboratory modeled after Fredersen’s late wife Hel, whom Rotwang desired. After Rotwang helps Fredersen discover the secret catacombs where Maria is organizing the workers, Fredersen convinces Rotwang to cast his robot in the likeness of Maria so he can infiltrate and control this movement. Rotwang agrees, secretly planning to use the false Maria to destroy Fredersen’s beloved Metropolis. This is not to mention a further array of characters: Freder’s downcast and unfavored brother Josaphat (Theodor Loos, M); the Thin Man (Fritz Rasp, Diary of a Lost Girl), whom Fredersen hires to trail Freder; the worker Georgy (Erwin Biswanger, Die Nibelungen) who trades identities with Freder and becomes dazzled by the sinful thrills of the club called Yoshiwara; or Grot (Heinrich George, She), who guards the Heart-Machine that keeps Metropolis stable. All these characters will crash into each other, the Heart will be stopped, and the city will come tumbling down. Lang orchestrates the destruction with glee.

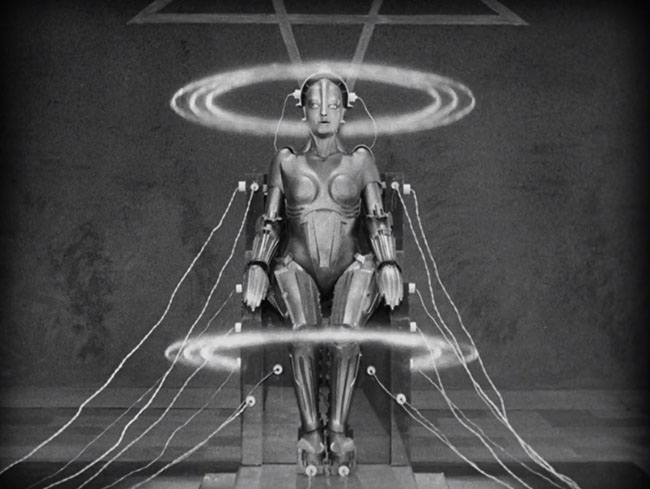

Rotwang’s robot begins its transformation.

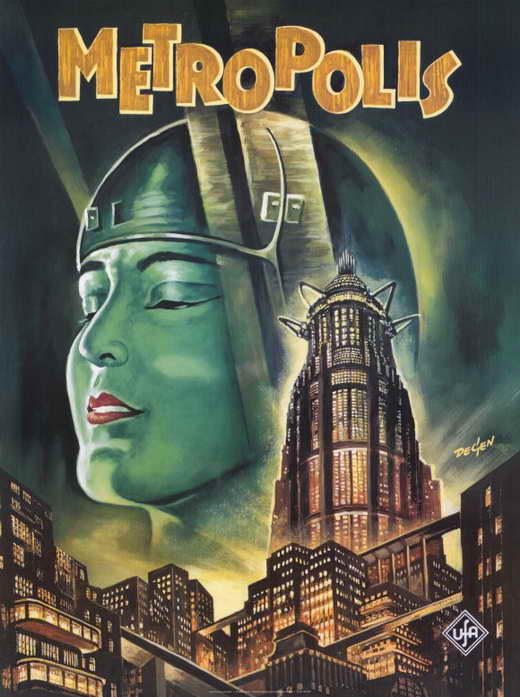

Yet the film’s length and overtly allegorical nature worked against it; the film was poorly received on release and survived only briefly in its original form. A German film that was partly intended to win over American audiences with its spectacle, it was exported to a Hollywood that demanded big cuts. Given the variable rates of speed that silent films could be projected, it is more helpful to express the length in meters rather than running time; Metropolis was shortened from its premiere length of 4,189 meters to about 3,100 meters, sacrificing significant character motivation and a great deal of coherency. In Germany it was withdrawn and also cut, to 3,241 meters. But even in this maimed form, the power of the film’s imagery was enough to cement it in the imagination of pop culture. Movies borrowed from it; they also reacted against it (see H.G. Wells’ Things to Come). Rotwang’s robot, before it takes the likeness of Maria, has become one of the most immortal sights offered by the cinema, and frequently appears on the covers of books chronicling the history of science fiction film – she even directly influenced the design of C-3PO. (She was also ahead of her time, not just a robot but an android, and thus holds up much better to 21st century eyes than the boxy robots of 1954’s Gog, or, for that matter, the Daleks of the past or present Doctor Who.) The impossible skyscrapers and their implicit futurism became a required shorthand for any utopian or dystopian SF film to follow; never mind that Lang was merely drawing from the sights of his trip to New York City. Rotwang became a number of mad scientists that followed, not least Dr. Strangelove. The machines that power Metropolis, which also count the 10-hour workday, were resurrected for music videos and TV commercials. Not bad for a film that couldn’t be properly viewed for 83 years. Following a number of valiant attempts at reconstruction using scattered recovered footage from different uncovered versions of the film, photographs of deleted scenes, censorship cards featuring detailed story notes and the full text of the intertitles, and even screenwriter Thea von Harbou’s original novelization, in 2010 the film was finally restored to nearly its original length (only a few minutes’ worth of footage is still missing). The source was a print of the Latin American export of the film, which had found its way from a private collector into an Argentinian film archive. Though the original 35mm print had been destroyed due to the dangers of storing flammable nitrate film, prior to this the archive had transferred this long cut of Metropolis to 16mm. In fact, the entire film was a different Metropolis than had been seen before: Lang shot his scenes using multiple cameras aligned side by side, and thus the Latin American Metropolis used slightly different angles but also some different takes of the same scene. But what was most valuable to Metropolis historians were the missing scenes, and when viewed in context, the story suddenly acquired a cohesive narrative and substantive meaning that had been missing during all those decades that the shorter cut had stubbornly become a classic.

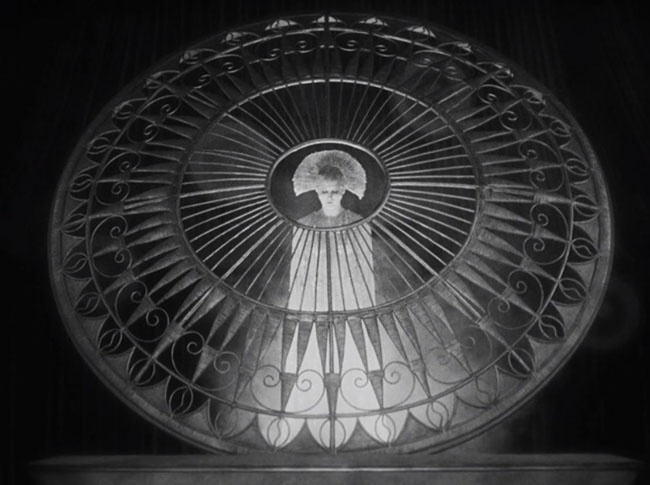

The false Maria (Brigitte Helm) introduces herself to the Yoshiwara club.

This year marks the film’s 90th anniversary, and the U.K.’s Masters of Cinema label has just released a definitive three-disc set, presenting not just the miraculous 2010 restoration, but also the prior restoration from 2001 and the 90-minute, midnight movie 1984 cut by composer Giorgio Moroder. Checking in with these different incarnations of Metropolis is to step through the history of the film’s re-emergence and piece-by-piece reassembly. Moroder’s film is of particular note, since it uniquely straddled the line between sincere restoration attempt (it really was the best and most accurate presentation of the film’s story for many years) and pop art appropriation. Moroder added his synthesizer scoring and laced in songs from Freddie Mercury, Adam Ant, Pat Benatar, Bonnie Tyler, Loverboy, Billy Squier, Jon Anderson, and Cycle V. The footage was presented tinted, with many scenes colorized in stylistic ways, most notably in Rotwang’s laboratory. Essentially, Moroder was making a silent film accessible to younger audiences by transforming it into a 90-minute rock musical/music video. For a long while, the VHS was a video store staple and quite possibly the easiest way to see Metropolis (apart from cheapo, barely watchable public domain releases – some, I can vouch, without any score at all) – and then it vanished until a Blu-ray release in recent years. It’s nice to see it here, although it’s less likely you’ll be checking in with Disc Three’s 2001 restoration, since it’s long since been overshadowed by the superior 2010 version. Most of all the value of the Masters of Cinema release is its comprehensive look at a film that never quite got its due until very recently, and yet, somehow, still conquered the world. You may still argue that the film’s ending is pat and naïve, that the characters are paper-thin, that the narrative doesn’t hold a candle to the spectacular sights, that perhaps the movie is more machine than human. And yet, in a way, Metropolis is still everywhere, and in looking closer at the 2010 restored cut, even through the shower curtain of scratches worn into the Argentine print and preserved in amber in its 16mm, you can see Lang’s youthful energy, astonishing Brigitte Helm twisting her body into severe angles in a machine’s notion of dancing sexy, the occultism of Rotwang’s lab clashing with the eerie, German Expressionism in the Biblical images, the fiery furnaces of the Lower City and the crashing Flood that deluges in the last act and sweeps the teeming extras together, and you can see that this is what filmmaking is supposed to be: original celluloid mythmaking.