While out driving with my father-in-law earlier this summer, he decided to take me on a short detour past the Dodge Correctional Institution in Waupun, Wisconsin – once known as the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. This, he pointed out, once housed notorious serial killer and grave-robber Ed Gein. The place looks like a medieval fortress, with high walls and turned inward upon itself, revealing nothing. A block away in any direction of this grim place is residential housing – small town Wisconsin literally in its shadow. Gein, like Jeffrey Dahmer, is one of Wisconsin’s morbid curiosities, kept alive not just in films and documentaries (a Wisconsin Film Festival screening of a Dahmer documentary a few years back was packed with attendees, and guests included those connected to the case), but in high school cafeteria conversations and supper club anecdotes over brandy Old Fashioneds. I currently live within 5 miles of the Mendota Mental Health Institute, which is where Ed Gein died in 1984. It’s likely more Wisconsinites know macabre details of Ed Gein – who in his Plainfield home reassembled the bones and flesh of corpses into lamps, belts, chairs, and corsets – than they do basic facts about Wisconsin history. Which is natural. Once you learn about Gein, details stick with you. He was all about the details. Two years after Gein’s arrest in 1957, Robert Bloch published Psycho, adapted to film a year after that by Hitchcock. Though Bloch’s plot was not directly influenced by Gein, upon learning of the case he was struck by the similarities (in particular Gein’s obsession with his mother) and inserted a nod to the Plainfield crimes. But it wasn’t until a young director and documentary photographer named Tobe Hooper decided to make a low-budget horror movie, co-written by Kim Henkel, that the true horror of Gein’s crimes was captured on film. Of course, Hooper relocated the action to Texas, added a chainsaw, and gave us not one but a family of Geins.

Decorations in the Leatherface family home were by art director Robert A. Burns and drew inspiration from Ed Gein.

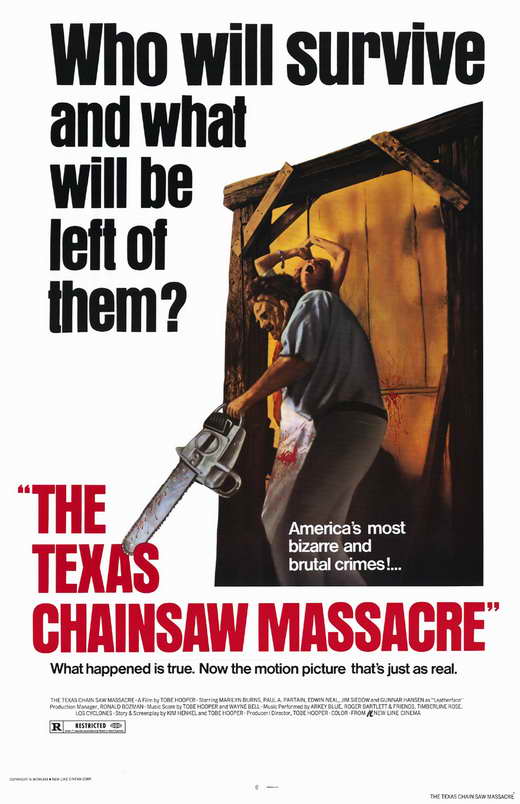

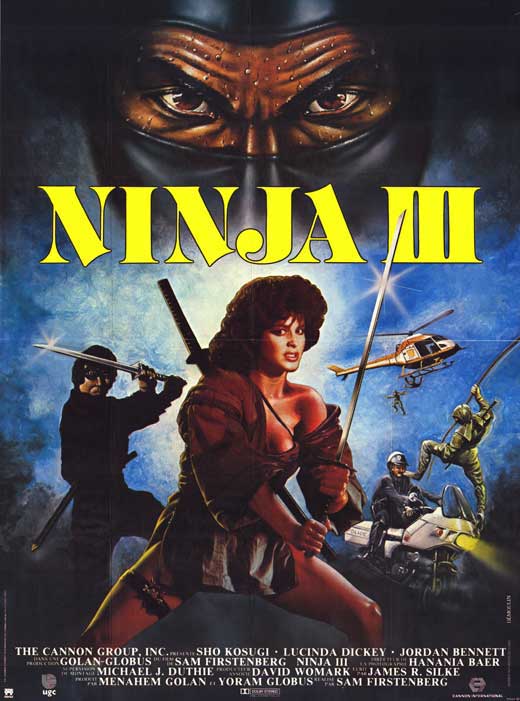

Hooper passed away this last week at the age of 74, and the tributes have poured in. His greatest lasting contribution to the horror genre will remain The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), but he moved from there into a very interesting and at times underrated career, always ready to bring a certain unhinged sensibility to the material, favoring a lean toward madness in the final acts. Even the lovely big-budget exploitation schlock of 1985’s Lifeforce – his true follow-up to Poltergeist (1982) with its ethereal, swirling special effects linked to the fleshy physical – achieves a frothy-mouthed fever pitch that makes it stand out. Despite some high-profile gigs, he could never escape the shadow of Chain Saw, like those homes snug against the walls of Waupun’s correctional institute. Its impact looms large. When he was asked to make a sequel to the film as part of a multi-picture contract deal with the Cannon Group, he obliged by taking the premise in a completely different direction: grand guignol comedy. It was the natural next step, given the gibbering insanity of the film’s final images. Horror at that level can only proceed to the ludicrous, and bring on Dennis Hopper locking chainsaws against Leatherface. Nonetheless, it was followed by more sequels and remakes by other hands, trying and failing to capture what made the original so special. And it’s not just this franchise. Many slasher films of the late 70’s and 80’s looked to Hooper’s film for inspiration, and Rob Zombie has practically built a filmmaking career on emulating the plot and style of the 1974 original. I first watched this film in a friend’s college dorm room, on a small TV screen and as part of a double feature with the second Hellraiser. Chain Saw was such a notorious film that I had to work up the courage. The film left me rattled, but not in the way I was expecting. I thought it would be a gore fest (like, well, the Hellraiser movie). Instead I got a film that terrified by being relentless, a film that captured the quality of a nightmare: run, run, run, jump through windows and try to flag down cars, but the evil is always a few inches behind you – with a smoking buzzing chainsaw. Nothing you do makes a difference. As everyone has pointed out by now, the film is not particularly grisly. Like Psycho before it, montage plants images in your mind which are not actually there, most famously in the meat-hook impaling of a young woman (Teri McMinn) by Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen). Yes, it points out Hooper’s uncanny artistry with conceiving and editing his terror scenes, a Hitchcock for the slaughterhouse, but there is something a bit disingenuous about this observation – like pointing out that some wall-to-wall sex movie doesn’t actually feature penetration. You still wouldn’t take your mother to go see it. Chain Saw takes no prisoners. It’s funny to think that Hooper thought he would get a PG (we only see a chainsaw pierce flesh once, and that’s when Leatherface accidentally cuts his own leg). When you’re playing around this deep inside the audience’s nightmares, technicalities of explicitness don’t matter much.

Stalked under the sun: Hooper’s camera creeps low from behind each victim.

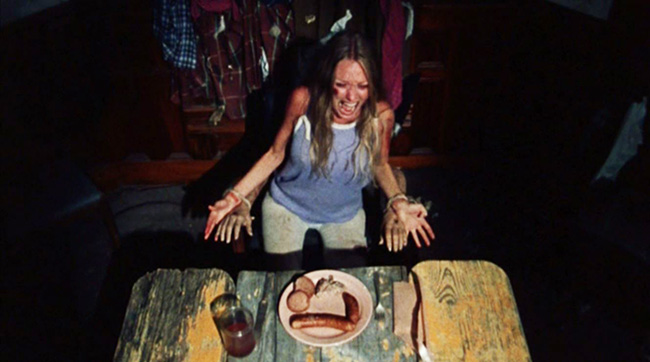

Think about when you’re having a nightmare – how your brain fills in the details. I may understand something in the narrative of my dream which it doesn’t lay out for me. I may know something about shadow-figures that chase me which I am never told; I don’t question the details of the location or my circumstances, I accept them. There are possibly even elements which are disturbing to me because they’re drawn from my subconscious, inextricably personal. I describe it to someone the next morning and it doesn’t make any sense to them, or lacks the impact. Something is missing. Better to keep such nightmares to yourself. Hooper works to make this a personal nightmare that can be shared by everyone in the theater. His style here is to emphasize subjective shots. We peer through the screen door into the menacing home with its glimpse of a red wall decorated with animal skulls; we follow close behind each victim as they approach the home, Hooper’s camera dollying low behind them and pointed up, emphasizing the sun piercing the canopy of trees or a heavy sky. When Sally (Marilyn Burns) is tied to a chair made partly of human remains, facing a dinner table and a close-knit clan of cannibals, Hooper cuts between two angles: her own, with the faces leering at her/us, and a God’s-eye view, emphasizing her helplessness and allowing us a brief detachment to take in the whole scene. This leads to the film’s exclamation point apex, a super-close-up of Sally’s eyeball as it twitches to take in all the horror: subjectivity perversely inverted, seeing nothing but the eye. Hooper embraces the Uncomfortably Close, whether it’s the birthmarked visage of the psychotic hitchhiker (Edwin Neal) or Leatherface’s sagging mask made from a human face – given some rouge when Leatherface goes in drag to play mama at the dinner table. The tactic gives the film an obscene quality which is why I think the argument that the film is not explicit is interesting only to those who want to study technique. There is not a second of the film which is not deeply uncomfortable, even before anything starts happening: the opening camera flashbulbs briefly illuminating disturbed remains; the corpse-sculpture set upon a tombstone against a blood-orange sky; goddamn Franklin (Paul A. Partain) doing or saying anything.

God’s-eye view of Sally (Marilyn Burns) at her most hopeless moment.

As in a nightmare, certain elements and ideas are planted that make sense without exactly making sense. The hitchhiker, after cutting both himself and Franklin, leaves an occult-like mark on the side of the travelers’ van. Franklin obsesses over it, wondering if they’ve been marked – if the Manson Family reject will try to follow them. Nothing comes of this, because the five young people will walk right into the slaughterhouse on their own. When the kids visit a cemetery, it’s a crime scene, and the sheriff is lying drunken on the ground, muttering to himself. One of the girls reads a horoscope at the opening of the film, indicating some ominous cosmic arrangements. We might subconsciously link her little dialogue to the frequent shots of the sun, which seems to sear straight through the camera negative. In fashion with the rest of the film, even the sun gets its own extreme close-up: the opening credits play over footage of solar flares. What does this mean? Who knows? Something terrible is in store. As night falls, Hooper trades this out for shots of a full moon, and sure enough, lunacy comes out to play. We never get a clear idea of the history of this family or how they function in their dilapidated, ossuary-like home, and yet when we see them all dressed up for dinner, Leatherface in drag, slaughterhouse patriarch Grandfather (John Dugan) like a zombie at the head of the table, the gas station owner (Jim Siedow) reprimanding bad behavior, claiming that killing doesn’t suit him even though he acts as cook – we get enough to understand. At least, we understand as much as Sally does in the moment: this is bad and we need to get the hell out. Ironically, the most meaningless gesture in the entire film is the opening crawl, read by a pre-fame John Larroquette, which tells us:

The film which you are about to see is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin. It is all the more tragic in that they were young. But had they lived very, very long lives, they could not have expected nor would they have wished to see as much of the mad and macabre as they were to see that day. For them an idyllic summer afternoon drive became a nightmare. The events of that day were to lead to the discovery of one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

This, followed by a specific date, indicates we are about to witness a true story, but it’s a Fargo-style con, despite the Ed Gein antecedent. An account of a true tragedy? Not really. The claim that the film is about “Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin”? Not really. The Zodiac, the full moon, the symbol on the van, the discovery in the cemetery, the old house belonging to the Hardesty family, does any of this matter? No. Not really. Sometimes there are just crazy people who want to kill you.

Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) revs up.

What I didn’t notice in that initial dorm room viewing was Hooper’s sense of humor. Black comedy, sure, but it becomes more clear on subsequent viewings. I certainly didn’t laugh the first time I watched the killing of Jerry (Allen Danziger), but now I can’t help but see the comedy in Leatherface’s reaction after he puts Jerry down: running to the window, looking desperately to see how many other teenagers are going to come stealing onto his property, then just holding his head in his hands, overcome with anxiety. More often appreciated is the pitch-black slapstick when Sally is offered up to Grandfather for slaughter. Leatherface keeps putting the sledgehammer in Grandfather’s hand, but he’s too weak to hold it, dropping it into the bucket below Sally’s head time and again. She gets free only because of the incompetent chaos. The film is also fascinating structurally. The gas station owner and the hitchhiker are introduced as random characters on the road, but they return in the second half of the film – the former revealing his true nature unexpectedly, the latter with the lurching feeling of Oh no, not him. Certain scenes in the film’s two halves are paired. The hitchhiker’s slicing of his palm becomes the slicing of Sally’s hand to feed Grandfather. It’s a moment even anticipated in Franklin’s pondering of whether you’d have the nerve to cut your own hand, like a morbid fascination that becomes very immediate, real, and unwelcome. Sally’s apparent fate to be sledgehammered is foreshadowed heavily by Franklin’s discussion of how many blows it takes to kill a cow. Sally herself becomes a grotesque – in this case, blood-drenched – hitchhiker in the final minutes of the film, hoping someone will pull over to help. Instead of being a passenger driving safely past, she has now become a part of the merciless Texas desert, those neglected, seemingly deserted farms and ranches, cattle escaped from the killing floor.

Cans kicking in the wind.

That’s the point – Hooper is asking you to get up close and personal with what you’d normally just drive past, barely giving a glance. That’s why he shows you spiders clustered in dark corners, why his camera lingers with a fetishist’s eye on every bone and skull that’s arranged in the upstairs room, why his camera shifts past the tied-up Sally to take note of the dinner table’s lampshade, which is a human face, its eye-holes and mouth stitched shut. At times the film is the equivalent of stopping to read the story of Ed Gein, absorbing the details because you can’t not. Note that the generator outside the house, running with the sound of a chainsaw, has WISCONSIN stamped on its surface. Hooper’s film is in lineage with Gein and his ilk, just as it’s tied to Bloch’s and Hitchcock’s Psycho. The interior of Leatherface’s old country house is architecturally identical to the Bates home. The stairs look ominous, and the audience is asked what terrible things they might see if they walked up them. But even more ominous is what’s beyond the stairs. In Hitchcock’s film, it’s a descent to the basement and the discovery of Norman’s mother (which gets an homage here in the attic, the Grandmother’s corpse seated across from the living-corpse Grandfather). In The Texas Chain Saw Masssacre, it’s the red room with mounted skulls. It looks like the portal to Hell – and we don’t know at first that this workspace of Leatherface’s seals with a slamming metal door. Hooper, in rooting deeper into the Ed Gein influence, transforms this domain into a more historically-accurate house of death that Hitchcock could never get away with in 1960. But Hooper’s genius was in knowing that the audience would still want to step inside. We have to.