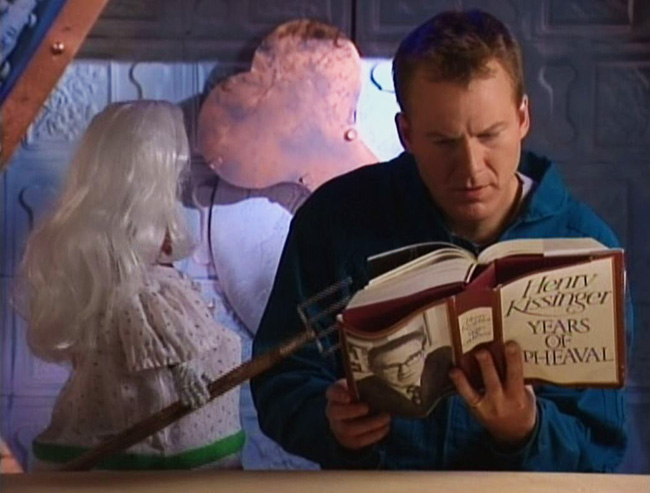

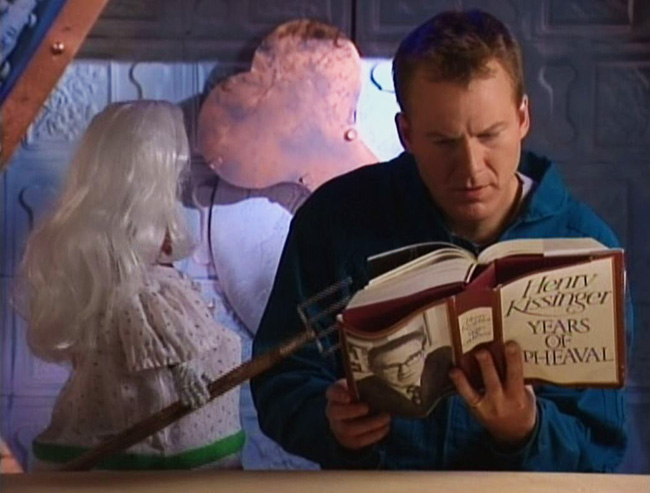

This week Shout Factory announced that the forthcoming DVD box set of Mystery Science Theater 3000 episodes, Volume XXXIX, will likely be the last (“Girls Town,” “The Amazing Transparent Man,” and “Diabolik” will be included in the set out November 21, along with a disc of comprehensive host segments culled from the 12 remaining unreleased episodes from its cable TV run). The cult TV show, which introduced “movie riffing” to the world, has enjoyed a major revival this year with an eleventh season on Netflix. Under the aegis of creator Joel Hodgson and featuring an all-new cast, the series was brought back thanks to a record-setting Kickstarter campaign, and is currently touring the States as a live show, the “Watch Out for Snakes Tour.”

But MST3K has always been difficult to release on home video because the film featured in each episode would need to have its rights negotiated individually. Rhino launched the effort in the late 90’s with VHS releases of episodes like “Pod People,” “Catalina Caper,” “Red Zone Cuba,” and more. They transitioned to DVDs beginning with “Eegah” in 2000, and launched the current box set series (4 discs each) in 2002. Though Rhino had its share of rights issues over the years – including releasing and quickly withdrawing “The Amazing Colossal Man” (on VHS) and “Godzilla vs. Megalon” (in a DVD box set) – they championed the series and kept it alive as a cult property in the years following its Sci-Fi Channel cancellation. Beginning in 2008, Shout Factory licensed the MST3K property and resumed the box set series using the same numbering – even instituting a standard release schedule of three volumes (or 12 episodes) per year. Episodes which no one thought would get released, such as the “Sandy Frank” films including all the MST3K Gamera movies, finally received official releases. It’s no small achievement that in the end, Rhino and Shout Factory have been able to release 164 of its original 197 episodes, in addition to Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (1996). (The first 21 shows, for the Minneapolis station KTMA, have never been seriously considered for release given that Hodgson views them as just a training ground for the series proper. However, the first two were released digitally earlier this year as an exclusive to Kickstarter backers.)

So let’s celebrate what has been done to get classic MST3K back in the public eye by looking at some of the best episodes from the series’ run, one for each of its eleven seasons (excluding KTMA). Each of these episodes received an official DVD release, with the caveat that some may be out of print, and Season 11 has not been released on physical media yet – though if you have Netflix, you can watch it now. One more thing – I am avoiding the more obvious episode choices and the popular-consensus classics (“Pod People,” “Manos: The Hands of Fate,” “Space Mutiny,” “The Final Sacrifice,” etc.) – in favor of “deeper cuts.”

SEASON 1 (The Comedy Channel, 1989-1990)

Women of the Prehistoric Planet

Experiment #104

Host: Joel Hodgson

Year of Film’s Release: 1966

Genre: Space voyage

DVD Release: Volume 9 (2006)

If KTMA was the proving grounds for MST3K, its debut season on The Comedy Channel presented a more disciplined show (they now wrote the riffs in advance, for one thing) that was just a little rough around the edges. Although the jokes are much more frequent than on KTMA, for many episodes the pace is considerably slower than seasons to come. The hosting segments feature Josh (“J. Elvis”) Weinstein as Dr. Erhardt, assistant to Trace Beaulieu’s Dr. Clayton Forrester; Weinstein also co-wrote the theme song with Hodgson and provided the voice for Tom Servo, but would depart before the second season. (He was later part of Hodgson’s live MST3K reunion project, Cinematic Titanic, where he was consistently one of the funniest performers.) Late in the first season, the show finally begins to hit its stride. Don’t let the low production number fool you – “Women of the Prehistoric Planet” was actually the last episode to be produced for this season, which explains why it includes callbacks to episodes like “Robot Holocaust.” The film’s plot is one that would be featured time and again in the series: a spaceship full of two-dimensional pulp archetypes crash lands on a primitive alien world. Separated from the rest of the crew, officer Linda (Irene Tsu) becomes a scantily-clad Jane to the planet’s Tarzan (Robert Ito). This is the episode which gave us the recurring riff “Hi-keeba!” – an inexplicable phrase that accompanies a clumsy karate chop, and which became a favorite of staff writer/performer Frank Conniff. Note: The Rhino DVD is currently out of print, but Shout Factory has been re-releasing the Rhino sets one at a time, with Volume 6 due in October.

SEASON 2 (The Comedy Channel, 1990-1991)

Rocket Attack U.S.A.

Experiment #205

Host: Joel Hodgson

Year of Film’s Release: 1961

Genre: Cold War doomsday thriller

DVD Release: Volume 27 (2013)

I started watching the show while the second season was airing, so this season has always had a special place in my heart (my first episode was “Jungle Goddess”). The second season introduced Kevin Murphy as the voice of Tom Servo and Frank Conniff as “TV’s Frank,” second banana to Dr. Forrester. Though some have argued that it would take another year before the show would come into its own, I really think all the elements come into place here – specifically, with “Rocket Attack U.S.A.,” the first episode to feature a “stinger” after the end credits. The stinger was a moment – just a few seconds – highlighting one of the more bizarre moments from the film, and the first is memorable: a blind man wandering through a street that’s been evacuated in advance of a nuclear attack. Without a drop of passion he delivers the line, “Help me.” It’s awkward, sad, shameless, and very funny. The film itself is an apocalyptic downer – much like the season 6 episode “Invasion USA” – beginning as an espionage thriller behind the Iron Curtain and ending with widespread nuclear holocaust. But doses of sleaze, terrible accents, and abrupt changes in tone provide plenty of fodder for classic MST3K. For other wonderful episodes that received an official release, you can check out “King Dinosaur,” “Wild Rebels,” or “Lost Continent.”

SEASON 3 (Comedy Central, 1991-1992)

Gamera vs. Guiron

Experiment #312

Host: Joel Hodgson

Year of Film’s Release: 1969

Genre: Kaiju movie

DVD Release: Volume 21: Gamera vs. MST3K (2011)

Comedy Central showed faith in one of its flagship shows by renewing it for a sprawling 24-episode third season. It says something for this season’s quality that the first three episodes are all regarded as classics of the show’s entire run: “Cave Dwellers,” “Gamera,” and “Pod People.” Gamera, a giant fire-breathing turtle that can fly, might be considered the goofier, less popular cousin of Godzilla. MST3K had first riffed Gamera movies at KTMA, and took them out of their back pocket to help fill out this longer-than-usual stretch of original episodes. Gamera vs. Guiron was the fourth of five Gamera films they would do this season, and it’s the most absurd and entertaining. (Honestly, other Japanese movies they riffed this season – Time of the Apes, Fugitive Alien, Star Force: Fugitive Alien II, and Mighty Jack – all feel like part and parcel of the same series.) In Gamera vs. Guiron, two kids stowaway on a space ship to a world on the far side of the Sun and match “wits” against two beautiful female aliens. Gamera faces off against this planet’s monster Guiron, which has a serrated knife for a head. This episode is an excellent example of the colorful sets, nonsensical plotting, and surreal giant monsters of the Gamera series, as well as the atrocious dubbing by Sandy Frank’s company. (Unfortunately, the Gamera box set is currently out of print.)

SEASON 4 (Comedy Central, 1992-1993)

Monster a-Go-Go

Experiment #421

Host: Joel Hodgson

Year of Film’s Release: 1965

Genre: Monster movie (but…”there was no monster”)

DVD Release: Volume 8 (2005)

No, there’s no monster in Monster a-Go-Go, but the true genre for this isn’t “monster movie” but “the worst movies ever made.” Bill Rebane (who also made The Giant Spider Invasion and still lives in northern Wisconsin) directed this atrocious act against celluloid, the kind of “film,” like Manos: The Hands of Fate, The Creeping Terror, or Red Zone Cuba, that MST3K would drag out of obscurity to remind viewers that, you know, Battlefield Earth isn’t that bad. A space capsule crashes back to Earth and an irradiated astronaut (Henry Hite) goes on a rampage. Many people have conversations about things. Non sequiturs abound, including a telephone ring that is clearly just someone making a telephone noise. A narrator talks over the characters and generally wages war with the viewer: after a long build-up to a confrontation with the monster, the film suddenly ends, the narrator telling us, “Astronaut Frank Douglas was rescued alive, well, and of normal size, some 8,000 miles away in a lifeboat, with no memory of where he has been, or how he was separated from his capsule. Then who or what has landed here? Is it here yet, or has the cosmic switch been pulled?” Reportedly Rebane ran out of money before the picture could be completed, and Herschell Gordon Lewis (Blood Feast) re-edited and “finished” the film. Some find this movie punishing, but it’s so bad that it flips round to perfection, in my opinion. To top it off, the short that accompanies the feature – “Circus on Ice” – is one of MST3K’s best.

SEASON 5 (Comedy Central, 1993-1994)

The Painted Hills

Experiment #510

Host: Joel Hodgson

Year of Film’s Release: 1951

Genre: Lassie movie

DVD Release: Volume 31: The Turkey Day Collection (2014)

Season 5 may be the most significant season in the show’s history, for at its halfway point, host Hodgson left (with a quote from The 7 Faces of Dr. Lao) and head writer Michael J. Nelson took his place. It was the moment that proved the series could endure without Joel’s endearing, sleepy-eyed comedy or Gizmonic inventions. But the season was also significant for being consistently strong: “Warrior of the Lost World,” “The Magic Voyage of Sinbad,” “Eegah,” “I Accuse My Parents,” “Mitchell,” “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die,” and “Santa Claus” were here unleashed upon the world. More quietly spectacular is this Lassie vehicle, The Painted Hills, a kids’ movie that goes to some very dark and inappropriate places. For some reason, the filmmakers decided to go full-on film noir. Lassie’s master is murdered and she deliberately plots her revenge, her reactions and motivations given hilarious voice throughout by Joel and the Bots.

SEASON 6 (Comedy Central, 1994-1995)

Zombie Nightmare

Experiment #604

Host: Mike Nelson

Year of Film’s Release: 1986

Genre: Zombie movie

DVD Release: Volume 15 (2009)

With former Deep 13 janitor Mike Nelson sent to the Satellite of Love, the invention exchange was phased out over season 5, and Mike confidently settled into his role in season 6 as a more sardonic movie riffer who, in the hosting segments, finds the power balance severely in the Bots’ favor (he’s constantly being tricked or tortured, it seems). Zombie Nightmare is an 80’s Canadian heavy metal-driven slasher/zombie movie. Jon Mikl Thor, the iron-pumping frontman of the band Thor, plays a gold-hearted fellow killed by teenagers and brought back as a revenge-seeking zombie by his mother and her voodoo priestess friend. The film also includes a young Tia Carrere and Adam West as a corrupt police detective, because why not?

SEASON 7 (Comedy Central, 1996)

Escape 2000

Experiment #705

Host: Mike Nelson

Year of Film’s Release: 1983

Genre: Post-apocalypse

DVD Release: Volume 37 (2016)

This truncated, six-episode season marked MST3K’s abrupt end on Comedy Central. The channel’s interest in the long-running show had declined, and the crew were a bit distracted by the production of their first (and last) big-screen outing, Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie (riffing This Island Earth), directed by Jim Mallon. The movie came and went with barely a whisper, and with the series canned, it seemed for a while that MST3K had stumbled to a close. But that last episode was something: “Laserblast” featured a perfect feature to riff (Charles Band’s post-Star Wars exploitation movie), and the host segments parodied 2001 to end the series on an epic note. But if you’ve played “Laserblast” too many times, put on “Escape 2000,” which has Mike and the Bots tackling one of those Italian Mad Max/Escape from New York rip-offs. Almost the entire film is gunfire and (the same) extras falling down over and over again. Oh, there’s also a jovial man named Toblerone Dablone, and the repeated, repeated command to would you please just leave the Bronx. With Frank Conniff having left the series the previous year (and bowing out of MST3K: The Movie), this episode, like all in season 7, includes Dr. Forrester’s mother Pearl (staff writer Mary Jo Pehl), who will have a much larger role in the years to come…

SEASON 8 (Sci-Fi Channel, 1997)

Revenge of the Creature

Experiment #801

Host: Mike Nelson

Year of Film’s Release: 1955

Genre: Monster movie

DVD Release: Volume 25 (2012)

When the Sci-Fi Channel picked up the option on MST3K, the series experienced another soft reboot – a sign of just how versatile and resilient the show’s concept is. Mike Nelson, Kevin Murphy (Servo), and producer Jim Mallon (Gypsy) returned, but Trace Beaulieu (Crow/Dr. Forrester) did not. Bill Corbett (later of Rifftrax) stepped in as the voice of Crow, and would soon embody the Observer, who keeps his brain in a dish. Pearl Forrester (Mary Jo Pehl) also returned to continue the experiments of his son Clayton, but now she was a vivacious, sadistic megalomaniac, a more fully realized character than the Midwestern mom from season 7. Murphy would soon join her as the Planet of the Apes-inspired Professor Bobo. Season 8 was a long, healthy, and varied season, and I could pick from a number of classics – “Space Mutiny,” “Time Chasers,” “The Giant Spider Invasion,” “Jack Frost” – but I’m going with the season premiere because its release on DVD, which I never thought I’d see, spotlights just how tenacious Shout Factory has been in chasing down movie rights. Revenge of the Creature is the first sequel to The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and the Gill-Man is one of the iconic Universal monsters. MST3K had developed a relationship with Universal through MST3K: The Movie, and the eighth season included a number of Universal-licensed films. As Rhino and then Shout chipped away at episodes, the first half of the eighth season remained untouched for years, largely for this reason. Then Shout negotiated Revenge of the Creature, and the gates opened to other “untouchable” episodes like “The Mole People” and “The Leech Woman.” Revenge of the Creature isn’t a bad film, but like This Island Earth, it offers plenty of silly moments that make 90 minutes pass with ease (it also includes a cameo from Clint Eastwood). The hosting segments establish the new stakes for the Satellite of Love, as Mike and the Bots find themselves above a planet where apes evolved from men. As Professor Bobo succinctly explains, “Human civilization is dead and apes rule the world; everything you ever knew and loved is no more. Well, your movie this week…”

SEASON 9 (Sci-Fi Channel, 1998)

The Touch of Satan

Experiment #908

Host: Mike Nelson

Year of Film’s Release: 1971

Genre: Satanic horror

DVD Release: Volume 5 (2004, reissued 2017)

The Sci-Fi Channel imposed an ongoing storyline for season 8, and insisted upon Best Brains using SF-themed movies as much as possible. But those restrictions began to relax by the ninth season (thankfully, as the plot of season 8 doesn’t make any sense when viewed out of order and only weighed the comedy down). The Touch of Satan, from the director of The Babysitter AND Weekend with the Babysitter, is the kind of post-Rosemary’s Baby occult horror that filled the drive-ins in the early 70’s. A young drifter (not a babysitter) falls for a farm girl (also not a babysitter) whose deranged great-grandmother murders people with a pitchfork. At one point the girl brings the boy to a pond, points to it, and says “This is where the fish lives.” That’s a line that someone actually wrote for this film. I have spent almost twenty years now trying to figure out why someone would type those words onto a page and hand them to an actress to deliver. I am still tortured by those words.

SEASON 10 (Sci-Fi Channel, 1999)

Merlin’s Shop of Mystical Wonders

Experiment #1003

Host: Mike Nelson

Year of Film’s Release: 1996

Genre: Horror anthology

DVD Release: Volume 5 (2004, reissued 2017)

Like The Painted Hills, Merlin’s Shop of Mystical Wonders is an incredibly inappropriate children’s film – and this one features the death of two beloved pets. Actually, it’s not truly a children’s film – it’s not truly anything except a direct-to-video disaster editing together scenes from a 1984 film called The Devil’s Cat alongside a new story about a couple, unable to conceive(!), visiting Merlin the Wizard and stealing his spellbook, which wreaks horror-movie havoc. All this is a story read (for some reason) by Ernest Borgnine to his young grandson. The 1984 scenes are obviously from 1984, yet we’re supposed to believe that the Merlin storyline is seamlessly part of the same tale. At one point, Merlin goes in search of his possessed toy monkey, and asks strangers on the street – dressed in full wizard regalia – “Have you seen my monkey?” It’s the movie that will have you singing, “Rock and roll Martian/Rock and roll Martian.” Merlin’s Shop of Mystical Wonders was the last episode of MST3K to air on the Sci-Fi Channel, though it was intended to be the third (rights issues caused the airing delay). And then that was it…for eighteen years.

SEASON 11 (Netflix, 2017)

Yongary: Monster from the Deep

Experiment #1109

Host: Jonah Ray

Year of Film’s Release: 1960

Genre: Giant monster

DVD Release: TBD

After taking his movie-riffing project Cinematic Titanic on the road for a couple years, Joel was encouraged by the enthusiastic response and realized there was a market for a revival of MST3K. Joel and Shout purchased the rights from Jill Mallon and launched a Kickstarter, which met several stretch goals to ultimately fund 14 new episodes. But Joel didn’t want to return as host; he has said that he always envisioned the show being passed from one host to another. So acting as producer (and occasional guest star), Hodgson recruited a whole new cast: Jonah Ray as the new prisoner on the SOL, Hampton Yount as Crow, Baron Vaughn as Tom Servo, Rebecca Hanson as Gypsy, Felicia Day as Pearl’s daughter Kinga Forrester, and Patton Oswalt as TV’s Son of TV’s Frank, or Max for short. Following the Netflix streaming model, all fourteen episodes were available simultaneously. The benefit is that binge watchers could quickly watch the new cast settle in and improve as the series goes on: the riffing, which is much too fast (though still funny) in early episodes like “Reptilicus,” has a more relaxed and natural pace by the time you come to “Yongary: Monster from the Deep.” (Ironically, in the early seasons the riffing was too slow. There’s an art to this.) This unusual film is basically a kaiju movie for South Korea, and it feels like one of the classic Gamera episodes from the Joel era; there’s even an annoying kid in short-shorts who loves his giant monster while it kills everyone in sight. An unexpectedly grisly end for the monster Yongary has Jonah and the Bots asking if Werner Herzog directed the ending. As of this writing, fingers are still crossed for MST3K to get a twelfth season (optimistically, they end on a cliffhanger), but episodes like “Yongary” make it clear that the show can stick around for a very, very long time.