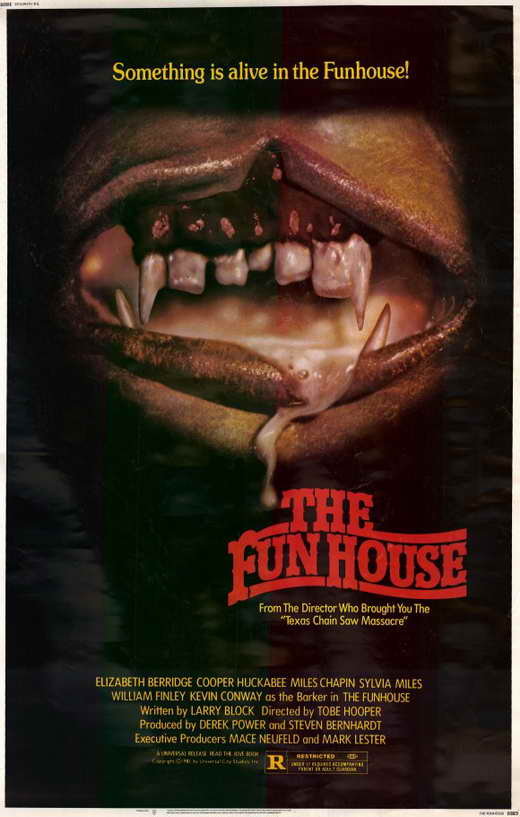

Before Poltergeist (1982), Tobe Hooper was a director of low-budget horror films whose reputation was built on the notoriety of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), an expertly crafted terror machine. After Poltergeist, things got messy: the film was a box office smash, but the heavy hand of producer/screenwriter Steven Spielberg tainted Hooper’s reputation, with some critics questioning how much credit for the film Hooper should take. His subsequent three-picture deal with Cannon Films, which gave us the distinctive and off-kilter films Lifeforce (1985), Invaders from Mars (1986), and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), nonetheless sealed the deal that Hooper would never again be regarded as a major commercial director. So, turning back the clock, 1981’s The Funhouse is all the more interesting. Coming off the cult classic TV miniseries Salem’s Lot (1979), it was his first theatrically released film in five years (he was replaced as director of 1979’s The Dark). He was at a major studio, Universal, and the film’s makeup artist was Rick Baker, who was soon to win an Academy Award for An American Werewolf in London (1981). The film also features evocative cinematography by Andrew Laszlo (First Blood, Innerspace). It’s not a prestige picture, but it’s a major step up for Hooper, a natural entry point to the big leagues of Poltergeist.

Teenagers trapped in the funhouse: Buzz (Cooper Huckabee), Amy (Elizabeth Berridge), Liz (Largo Woodruff), and Richie (Miles Chapin).

Universal may have expected a slasher film with a carnival-setting gimmick to cash in on the (quickly peaking) slasher craze, but if The Funhouse is a slasher, it’s one that’s more thoughtful and less formulaic than the many others swamping the drive-ins. The body count is low, and the killer doesn’t begin his assault until very late in the film. Hooper even begins by teasing the genre in much the same way Brian De Palma did in the opening of Blow Out (also 1981). We join the first-person POV of a stalker creeping through a house, then donning a mask and picking up a knife as in John Carpenter’s Halloween. A teenage girl disrobes and steps into a shower. Behind her, we can see the door opening, the first of several shots which directly replicate Psycho. But when the knife connects with her torso, the blade bends – it’s rubber. The girl, Amy Harper (Elizabeth Berridge, Amadeus) rips off the assailant’s mask to reveal her little brother Joey (Shawn Carson, Something Wicked This Way Comes). He runs away squealing while she threatens payback. This is shortly followed by the family gathered round to watch Bride of Frankenstein playing on TV. Right from the start, Hooper is framing this as a horror movie about horror movies and the pleasure we take in being scared. The metatextual approach is appropriate for a story set in a carnival funhouse, a place designed to offer safe jolts to those taking the ride. When our set of teenagers embark on the ride itself, jerked along in a moving cart, the film takes us through the whole journey, replete with sudden loud noises, sinister animated mannequins, and a giant eye that glows as it gazes; the film becomes the ride. Of course, then Hooper lets loose on actual horror when they make the fatal mistake of jumping out of their carriages to spend the night inside the ride. The carnival after hours turns out to be a very different beast.

Madame Zena (Sylvia Miles) reads Amy’s fortune.

Amy sneaks off to the carnival with her new boyfriend Buzz (Cooper Huckabee, Urban Cowboy), friend Liz (Largo Woodruff) and Liz’s boyfriend Richie (Miles Chapin, Hair). While the girls discuss the imminent loss of Amy’s virginity, Buzz subtly bullies his prankster buddy Richie. Hooper spends a lot of time with these four as they move through the carnival, attending freak shows (two-headed cows and a Mütter Museum-worthy fetus in a bottle) and peeping through a tent at a burlesque show with middle-aged strippers. Because we see most of this from Amy’s point of view, we get the same creepy feeling that she does when the ubiquitous barker (Kevin Conway, Slaughterhouse-Five, Paradise Alley) makes eye contact during his lengthy carny sermons. They also make stops for a magician (De Palma favorite William Finley, Phantom of the Paradise) and a fortune teller, Madame Zena (Sylvia Miles, Midnight Cowboy), who answers the teens’ mockery by angrily throwing them out. We don’t know exactly what role all these characters will play when the horror begins; the formula is not made clear. They may all be psychopaths, as in Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (1973). And for a while we barely even notice that strange character operating the funhouse, with his oversized mask of Karloff’s Frankenstein monster, though soon his true nature will emerge. A subplot has Joey following his big sister to the carnival, and investigating her disappearance after the crowd has dispersed and the lights are shut off. But Joey’s story is a red herring. Hooper’s film is designed with blind alleys, trap doors, and mirrors pointed at mirrors.

Kevin Conway as the carnival barker.

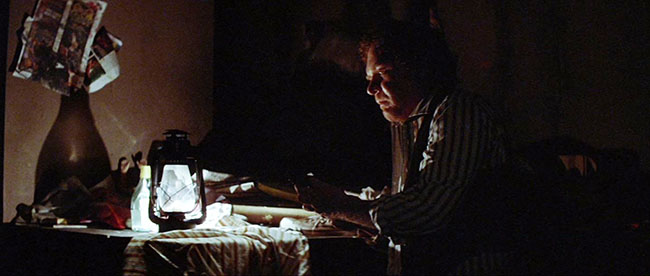

In fact, the story turns out to be fairly simple, but established on a surprisingly psychosexual and random turn of events. The giggling teens spy from the ceiling the Frankenstein-masked carny (Wayne Doba) offering cash to Madame Zena for sex, and she agrees. But his embarrassment over premature ejaculation and anger that she won’t give him his money back leads to her murder. Beneath his mask he’s revealed to be deformed, with red eyes, fangs, and long white hair. When surrogate father Conway discovers the murder, he acts to cover it up – until one of the teens accidentally drops his lighter from the ceiling, leading both the barker and his monstrous assistant to chase the kids through the funhouse. Rick Baker’s makeup is exceptional here, but Hooper keeps this carnival geek mostly in shadow, revealing only brief and startling glimpses. In fact, for much of the film he leans toward realistic lighting (characters are often in shadow) and subjective, voyeuristic shots (peeping at the burlesque performers; looking down into Madame Zena’s room). The emphasis is on the thrills of visiting a carnival, of trespassing on forbidden sights – and also to draw a line between theatrical scares (the Frankenstein motif and the garish, baiting illustrations for freak shows) and real-life horror. Throughout you can smell the sawdust and taste the cotton candy. Unfortunately, after all this rich build-up, it’s all over disappointingly quickly. But I suppose that’s how carnival attractions work, too.