“They’ve given you a number

And taken away your name.”

–“Secret Agent Man,” Johnny Rivers

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal ITV series The Prisoner starring Patrick McGoohan. To celebrate here at Midnight Only, I’m embarking on a comprehensive episode guide, taking an in-depth look at each of the 17 installments one at a time. (It’s long been a parlor game of fans to guess the “best” order for the episodes, since the original airing sequence in both the U.K. and North America is so unsatisfactory. I’ll be using my own preferred order for these reviews.) But before we leap into the head-spinning world of No.6 and the Village, we’re going to take a brief stop at the series which planted the seeds for The Prisoner, the spy show that made McGoohan a star: Danger Man. The series launched in 1960, two years before Sean Connery watched Ursula Andress step out of the sea in her white bikini and the spy craze exploded. It was principally the product of two men: Lew Grade, Managing Director of ITC, and Australian Ralph Smart, who had previously written for the 1958-1960 series The Invisible Man. Smart conceived of Danger Man with input from fellow Invisible Man writer Ian Stuart Black, and even briefly took meetings with Ian Fleming in the earliest stages of development. When McGoohan was signed, the actor further honed the character and concept to suit his liking. Danger Man told the adventures of a NATO agent, John Drake (McGoohan), who travels the world to thwart assassinations, expose double agents, and liberate valuable assets from behind enemy lines. Smart would write many of the scripts, and his name would prove apropos: the show radiated intelligence and expected the audience to pay attention and keep up with its fast-arriving twists. Apart from the basic premise of Drake on a mission week after week, Danger Man defied conventional episodic TV formulae, presenting challenging characterizations and morally complex dilemmas for its chilly protagonist to confront. Although The Prisoner has eclipsed it in popularity, Danger Man was a phenomenon of its own – even if its first run of thirty-nine episodes were broadcast without too much fanfare, and very few of them aired in the States as Grade had originally hoped. The program was cancelled in 1962, but as the appetite for superspies came to a boil, Smart’s espionage thriller once again became a commercial prospect. Production resumed in 1964, and the show was finally picked up for regular broadcast in the U.S. as Secret Agent. The theme song, “Secret Agent Man” as sung by Johnny Rivers, peaked at #3 on Billboard’s Top 100. The episodes were extended to an hour, and John Drake’s accent changed from American to English, his base of operations no longer NATO but the British M9 organization. Despite these changes, he wasn’t a 007 clone. McGoohan despised the sex and violence formula of Fleming, and was far more interested in his character solving problems with his wits. McGoohan also infused Drake with the actor’s own unique mannerisms: an enigmatic gleam in his eye, a slight exasperation and quickness to anger, and a bit of well-bred condescension. Of course he didn’t seduce women; with Drake, a sexual overture could only be a con, the requirement of an undercover assignment. His interior life was closely guarded, and he rarely expressed personal hobbies apart from those wide-ranging skills that could save his life in a pinch. Yet his heroics also lent him a basic decency. These traits would spill over into The Prisoner‘s No.6, spurring decades-long debates as to whether No.6 was actually John Drake.

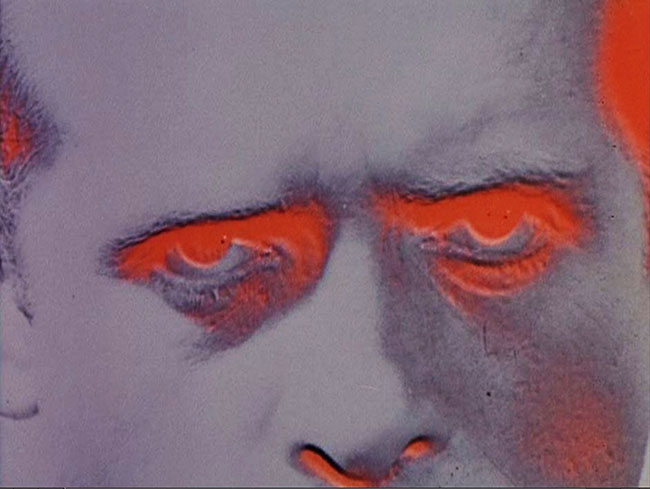

Patrick McGoohan as John Drake in “Koroshi.”

After two color episodes were filmed for a fourth series in 1966, McGoohan suddenly quit, turning his sights toward his personal project, The Prisoner: a show which would begin, critically, with No.6 abruptly resigning from his own successful career, baffling his superiors. A winking statement from McGoohan, perhaps? Those last two Danger Man/Secret Agent episodes, a two-parter called “Koroshi” and “Shinda Shima,” would not air until 1968, slipped into The Prisoner‘s regular time slot and further blurring the line between the two programs. The same year these two Danger Man episodes were also released together in the States as a TV movie called Koroshi. A two-parter that also works as two separate installments, Koroshi (as I’ll refer to the whole) sees Drake traveling to Tokyo to investigate the killing of one of their agents, uncovering the Order of Murder Brotherhood and their sinister designs against the United Nations. Here, at last, Drake seemed to venture into the world of James Bond, though it’s worth noting that these two episodes were filmed before the release of the Japan-set 007 outing You Only Live Twice (1967). This is especially true in “Shinda Shima,” in which Drake spends most of his time in a remote Japanese island’s underground lair, which is populated by martial artist assassins and a villain whose desk opens up to reveal a machine gun. The episode features a climactic underwater battle a la Thunderball (1965). “Koroshi” even includes a character named Tanaka, which is the name of Bond’s Japanese contact in both the novel and film of You Only Live Twice. But you might recognize this Tanaka as Burt Kwouk, better known as Cato of the Pink Panther films. (Sadly, Kwouk’s part is pretty miniscule.)

John Drake prepares for an assassination attempt in a room of kabuki mannequins.

When operative Ako Nakamura (Yoko Tani, First Spaceship on Venus) is killed in her room by an artificial flower that emits poison gas, Drake goes undercover as a reporter in Tokyo during its Festival of Fragrance. He meets two British expats, Mr. Sanders (Ronald Howard, The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb) and Rosemary Riley (Amanda Barrie, Carry on Cleo) who introduce him to kabuki theater, a performance of Hamlet which features a “koroshi,” or murder scene. Drake then finds himself alone in a room with kabuki mask-wearing mannequins, and as he walks amidst them, he looks for the one that might be real, bracing for an attempt on his life. Directors Michael Truman and Peter Yates (who was soon to make Bullitt) draw out the suspense masterfully in a scene that foreshadows a similar moment in Blade Runner. It’s far and away the highlight of these two episodes. Discovering another poison flower in Rosemary’s room and destroying it before she can be killed, he identifies Sanders as the man responsible for Nakamura’s murder. He escapes one more assassination attempt and follows Sanders to his cavernous HQ, where his Brotherhood preach the “poetry of death.” In a surreal touch that anticipates The Prisoner, a dummy with a metronome for a heart beats loudly to mark time until their next victim’s heart is stopped. Drake makes his appearance with a typically droll line: “In my case, Mr. Sanders, the poetry of death did not rhyme.” Sanders tries to make a getaway in a small plane, but Drake plays a game of chicken using a jeep on the runway, driving his man off the road and into a fatal explosion.

An example of the James Bond stylings of “Shinda Shima”: the Controller (George Coulouris) springs a machine gun from his desk.

“Shinda Shima,” directed by Yates, does not at first appear to be a continuation of the same story, despite the Japanese setting. But connections reveal themselves as the episode unfolds. Drake now takes the identity of a British electronics expert from “Q department,” Edward Sharp. While the real Sharp is detained, Drake investigates his briefcase riddled with secret compartments (shades of From Russia with Love). Each of these hiding places contains elements of a decryption device, which Drake helpfully identifies to the tune of “The 12 Days of Christmas.” Drake then delivers the components to the island of Shinda Shima, which earned this name – “The Murdered Island” – because of unexplained deaths that have sent the superstitious population into exile, fearing evil spirits. In fact the deaths were orchestrated by Controller (George Coulouris, Citizen Kane), a Blofeld type establishing his secret HQ much like the Japanese volcano base that would feature in You Only Live Twice. (Though the film was still in production at the same time as “Shinda Shima,” there are similarities between this episode, written by Norman Hudis, and the original Fleming. In Fleming’s novel, Blofeld takes residence in a castle on a Japanese island overgrown with poisonous flora, driving the locals away and affording him privacy for his world-conquering plots.) Drake begins negotiations to sell his decryption device to Controller and his army of martial arts-practicing henchmen – followers of the death cult from the previous episode – but when one of his own, a woman named Miho (Yoko Tani again), reveals that she is the sister of Ako Nakamara from “Koroshi” and seeks revenge for her murder, Controller asks Drake to electrocute her. This forces Drake to improvise.

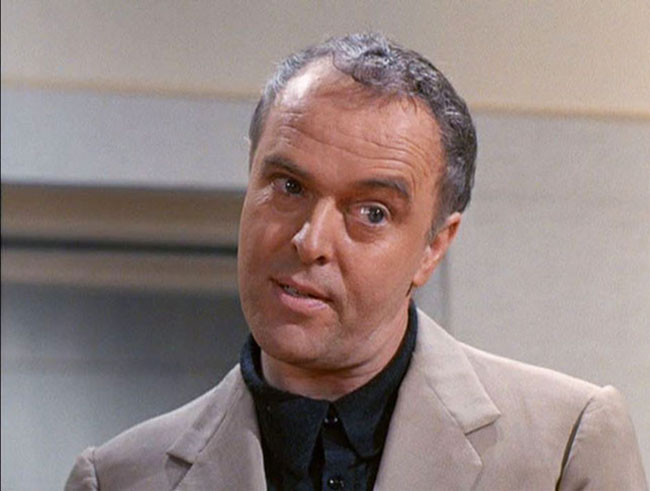

Kenneth Griffith – soon to be seen in “The Prisoner” – as the double-dealing Richards.

Although the Koroshi two-parter is not without the standard contemporary examples of yellowface, there is only one that is truly glaring. Otherwise Koroshi is refreshing for offering no Yellow Peril villains, but instead white British men: Ronald Howard in the first half, and both George Colouris and, as a greedy opportunist, Kenneth Griffith in “Shinda Shima.” In the finale, Drake and Miho stir up a revolt, bringing the local villagers back to the island to fight off the (almost universally white) invaders. Of course, for pulp like this, the villagers know their martial arts. Some have said the show’s turn, in these episodes, toward more standard spy adventure contributed to McGoohan’s abrupt decision to leave the series, just two episodes into its fourth series. Certainly Koroshi lacks the Ralph Smart cleverness, and, despite the program’s fresh change from black-and-white to color, these fail to represent the show at its best. But we do know that McGoohan was tiring of John Drake, and he had his own concept, The Prisoner, which he was eager to pursue one way or another. McGoohan was able to convince Lew Grade to proceed with this new project at ITV, and Grade had every interest in keeping his star happy. It’s unclear whether McGoohan ever proposed The Prisoner as a direct continuation of Danger Man – John Drake in the Village. Regardless, without Ralph Smart’s involvement, the name John Drake was certainly not going to be used. In an invaluable 1985 interview with Barrington Calia for New Video Magazine, McGoohan gave the following response to the question of whether No.6 was Drake: “No!…Unfortunately, people assume that The Prisoner is a sequel to Secret Agent because I began the project closely afterward. No.6 is a former ‘secret agent,’ which is why people maintain this false notion for the sake of continuity. I would’ve preferred someone else play the role, but circumstances wouldn’t have it that way.”

Drake’s contact, Potter (Christopher Benjamin), delivers the mission in “Koroshi.” His character would subsequently appear in an episode of “The Prisoner.”

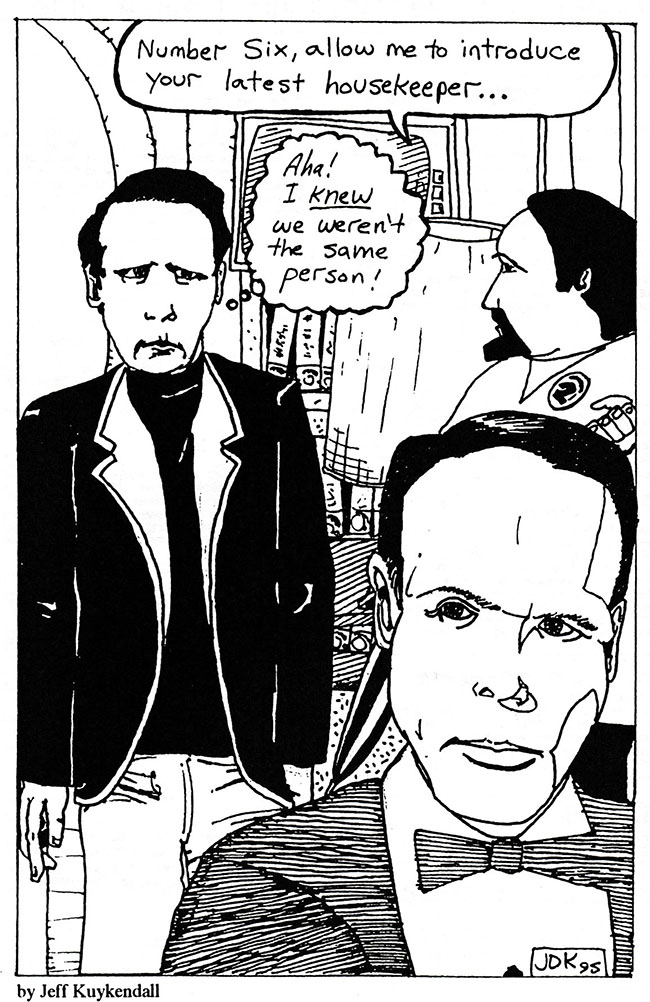

But, as we will see in the weeks ahead, The Prisoner at times encourages the viewers to draw connections to Danger Man, sometimes with apparent sincerity, at other times as in-jokes. As Matthew White & Jaffer Ali write in The Official Prisoner Companion, “Obviously some of the comparisons are encouraged within the show itself. And to top it off, several people involved with the creation of The Prisoner are quick to make comparisons with Secret Agent. [Script editor] George Markstein has stated for the record that No.6 was John Drake, no doubt about it. And Jack Shampan, who was the art director for the series, remembers his first meeting with Patrick McGoohan and producer David Tomblin. He was asked to ‘chat with [Tomblin and McGoohan] about doing a continuation of Danger Man that they were toying with the idea of calling The Prisoner.'” In 1995 I joined the American Prisoner fan club called Once Upon a Time. I wrote a Prisoner novella for the club (Soliloquy) and contributed some art for their magazine. The editor asked me to draw a cartoon for their Danger Man issue. At the time, even though I was fascinated by The Prisoner and had even visited Portmeirion, I had not seen Danger Man. I was born after it had originally aired, and it was almost impossible to find in those pre-DVD, early-Internet days. I was inclined to believe McGoohan, since he was the prime creative force behind The Prisoner, in his statements that John Drake was not No.6, so I drew a cartoon (below) showing the two characters meeting in No.6’s suite in the Village. Many years later, A&E released the full series on DVD, and I began working my way through them. The more I watched, the less convinced I was that John Drake was not No.6…

My 1995 cartoon for the Prisoner fan magazine “Once Upon a Time,” speculating on the No.6/John Drake connection.

The Danger Man website suggests that the third (and last complete) series of Danger Man depicts Drake reaching a “turning point” that will lead him to resign in the opening of The Prisoner: “Drake was much the same, still dedicated and cynical, but more and more the series was to show the down side of being a spy.” Six episodes are listed as tracing the disillusionment of Drake. I also noticed a little telling moment in the final episode, “Shinda Shima.” When the Controller says to the undercover Drake, “You would be more comfortable in one of our uniforms,” Drake demurs: “I am never comfortable in any uniform, thank you.” (In the Village, No.6 is always in the same outfit, defiantly different from the pinstripes of the locals, and he never dons his numbered badge.) But throughout the series there are connections to No.6. He demonstrates a resentment toward his superiors in episodes like the bitter, brutal “That’s Two of Us Sorry.” He follows the same rigid moral code as No.6, avoiding firearms and showing little interest in sex. McGoohan doesn’t seem to be invested in differentiating the two characters, even though he has portrayed a variety of roles throughout his career. Further shades of The Prisoner creep into Danger Man in “Colony Three,” about a spy school established by the Soviets to resemble a British village, and “The Ubiquitous Mr. Lovegrove,” a surreal, dreamlike excursion much like the Prisoner episode “A, B & C.” Of course many of the actors from The Prisoner first show up in Danger Man, including future No.2.’s Derren Nesbitt in “Sting in the Tail” and Kenneth Griffith in “Shinda Shima.” And the connection extends to the very first episode of the series, written by Smart and future Avengers creator Brian Clemens. It was filmed in an eccentric Italianate resort in Wales designed by architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis: Portmeirion. Later, this would become the iconic shooting location of The Prisoner, though audiences would get their first taste in six separate episodes of Danger Man. McGoohan was charmed by the little village, and as the concept for his next program began to take shape in his imagination, the selection of its ideal shooting location was inevitable.

Up next: ARRIVAL.