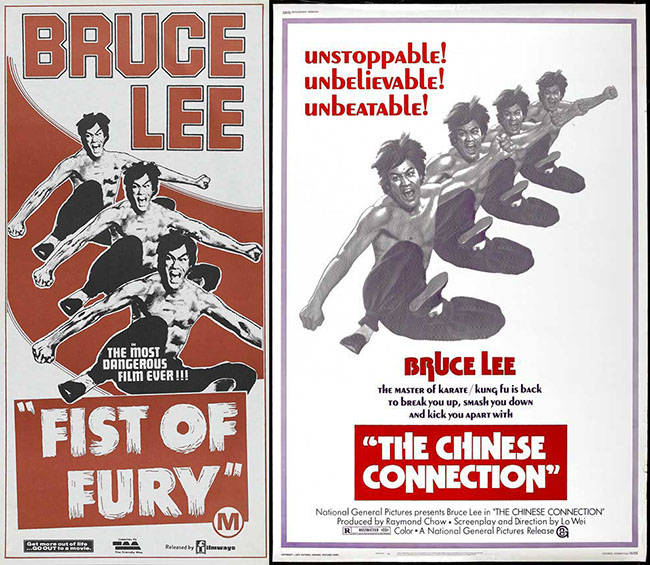

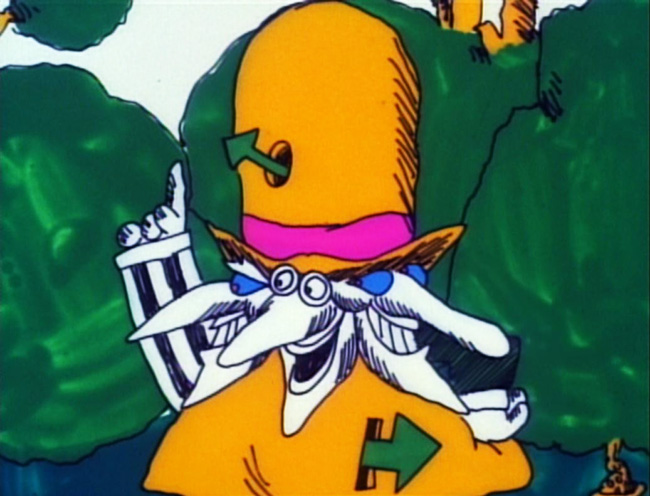

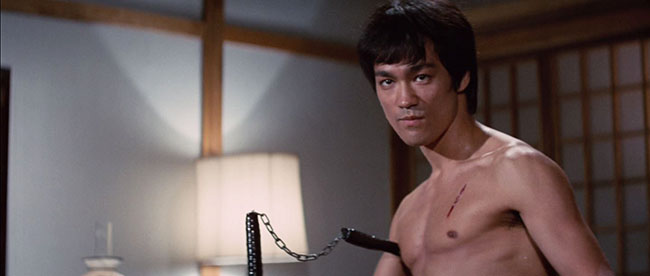

For his second major starring role following The Big Boss (1971), Bruce Lee reunited with director Lo Wei and Raymond Chow’s Golden Harvest for Fist of Fury (1972). Shout! Factory recently released both films as part of their Shout Select series, transferred from new 4K scans with much improved color and sharpness, although the cover art uses the alternate and notoriously botched American titles of Fists of Fury for The Big Boss and The Chinese Connection for Fist of Fury. (Flip the cover art inside-out to correct this odd misstep.) In Fist of Fury, Lee plays Chen Zhen, student of the legendary (and historical) martial arts master Huo Yuanjia (or Ho Yuan-chia, as the opening titles spell it), who died in 1910 in mysterious circumstances. That means that this is a period picture, though there’s at least one scene where the extras are clearly wearing modern (1970’s) dress. Never mind. Already in the opening scene, Lo Wei creates a more visually appealing palette than his earlier film, as Huo Yuanjia is laid to rest in a cemetery in a torrential downpour, his students gathered around the plot under their Chinese parasols. It is not the first time that the film will resemble a handsomely mounted Japanese samurai movie. All of Yuanjia’s pupils are dressed in black except for Chen Zhen, newly arrived and clad in a white Mao suit, the traditional Chinese color of mourning. He falls upon the coffin, clawing at its lid until he’s whacked on the back of a head with a shovel to render him unconscious. Inside Yuanjia’s Jing Wu School in Shanghai, Chen Zhen fasts in his grief, obsessed with the idea that his master’s death wasn’t by stomach flu, as he’s told, but instead was an assassination. Trouble arrives when the local Japanese dojo, led by grandmaster Hiroshi Suzuki (Riki Hashimoto) and his translator, Mr. Hu (Pin Ou Wei, The Way of the Dragon), present a mocking gift in memory of the late Jing Wu Master, a framed sign calling him the “Sick Man of East Asia.” Enraged, Chen Zhen wants to accept their challenge of a fight to see which school is the superior, but his master taught that martial arts were for physical fitness, not for fighting. It’s not long before Chen Zhen is driven to break that ideal to avenge his master’s murder.

Chen Zhen (Bruce Lee) at his master’s funeral.

In fact, a similar arc dominated The Big Boss, in which Lee swears not to fight, wearing an amulet to remind himself of his vow, but after an extended slowburn, Lee breaks his promise and unleashes rage and exquisitely choreographed fighting moves. His character is like a recovering alcoholic, and when he faces down The Big Boss himself, we see why: he kills his opponents brutally, as though he can’t help himself. He seems to go into a fog, and when he emerges, everyone around him is crippled or dead. But Fist of Fury, a much more efficient martial arts film, doesn’t waste much time turning Lee loose. His moral quandary – how to avenge his master’s honor, when his master expressly forbade the use of violence – doesn’t consume Lee for very long before he decides to fall cleanly on the side of revenge without mercy. In many ways, Lee is playing the same man, one whose desire to live in a peaceful world is undone, tragically, by the corrupt men who intervene in the lives of those he loves; and he falls off the wagon again. Here, his wish to marry the beautiful Yuan Li’er (Nora Miao, also returning from The Big Boss) is deferred permanently by his campaign against the Japanese dojo. The back and forth escalates; when he wipes out most of Suzuki’s pupils, Suzuki returns the favor, leaving some of the Jing Wu students dead. It’s a classic set-up for this kind of genre movie, but what’s interesting is that the Jing Wu school wants nothing to do with it. They’re drawn into a gang war entirely by Chen Zhen, and as Chen Zhen becomes a fugitive, by night hiding out in the cemetery by his master’s grave, by day donning disguises to infiltrate the Japanese school, the students of Jing Wu just want to find their problem student and talk some sense into him before anyone else gets killed. Chen Zhen follows a doomed path, leading to a wonderful denouement that is both tragic and strangely triumphant.

Chen Zhen battles Yoshida (Fung Ngai).

The intense racial rivalry and animosity between the Chinese and the Japanese fueling the plot was, again, historical. The film is set in the decades following the First Sino-Japanese War and following the Shanghai International Settlement which saw a rise in foreign settlers in the city, including the Japanese. The film also speaks to the invasion and occupation of Shanghai and China in the years to come, as Dwayne Wong (Omowale) writes in The Huffington Post: “Fist of Fury helped to exorcise some of the negative feelings that Chinese still had towards the ‘century of humiliation.'” This is evident throughout the film, including one notable scene where Chen Zhen is obstructed from entering a park by a sign that says “No dogs or Chinese allowed.” A dog is allowed to enter the park anyway, but he’s assured that’s because it doesn’t belong to a Chinese. (When Chen later camps out by his master’s grave, is that a dog he’s barbecuing?) The dojo features a Japanese garden straight out of the Toho back lot, a geisha gives a striptease to the saki-drinking villains in one scene, and both the instructor, Yoshida (Fung Ngai), and Suzuki wield samurai swords against Chen in the final battle. Lee answers Suzuki with his trademark nunchucks. He fights not just for the honor of his master, but as an act of nationalistic pride. This is populist filmmaking at its most sensationally effective, with a Chinese warrior confronting not just Japanese invaders but also a Russian colossus named Petrov (Robert Baker) to stick up for his fraught and battled-over country.

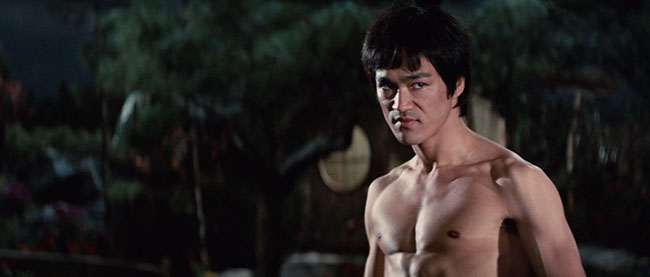

Chen in his final battle.

But the reason Fist of Fury plays so well to non-Chinese audiences is Lee’s charisma and martial arts talent. His down-and-dirty streetfighting moves, fast and savage, are coupled with a grace and athleticism that is always exciting to watch. When he enters a room of opponents, you can’t wait to see him let loose; while, per tradition, more challenging opponents, like the bosses at the end of each video game level, are set up with great effectiveness. (Petrov is introduced bending steel with his bare hands while Lee, disguised as a telephone repairman, watches from the corner.) The film also gives audiences more of what they want from Lee than The Big Boss did; that film moved Lee’s character only gradually into the center of the story as his multitude of friends fell to the villains, but Fist of Fury plays more like a star vehicle. Watch the moment when the messengers from the dojo depart the Jing Wu school, and all the Jing Wu students follow in a wave, leaving Lee standing alone, arrested in his outrage. He’s a loner from the start, so it’s no wonder that it isn’t very long before he’s wandering Shanghai on his own, setting into motion his multi-step plan of vengeance with cold-blooded calculation, like one of the Charles Bronson vehicles of later years. Chen Zhen became such a popular character that – despite the finality of its last freeze-frame – he was brought back to Chinese screens in subsequent years. Fist of Fury II (1977) and Fist of Fury III (1979) continued the plot with Brucesploitation actor Bruce Li in the Chen role. Though it didn’t feature Chen Zhen, another sequel, New Fist of Fury (1976), was an early attempt to launch Jackie Chan into stardom, under original director Lo Wei. (Chan has a very small role in the original Fist of Fury as one of the Jing Wu students.) Jet Li played Chen in the remake Fist of Legend (1994), which takes place in 1937. Chen also appears in the 2001 TV series Legend of Huo Yuan Jia, and the film Legend of the Fist: The Return of Chen Zhen (2010), with Donnie Yen. Not bad for a character who was invented for a quickie Bruce Lee movie. As for Lee himself, his next project was Way of the Dragon (1972), followed by his last fully completed film performance, in Enter the Dragon (1973).