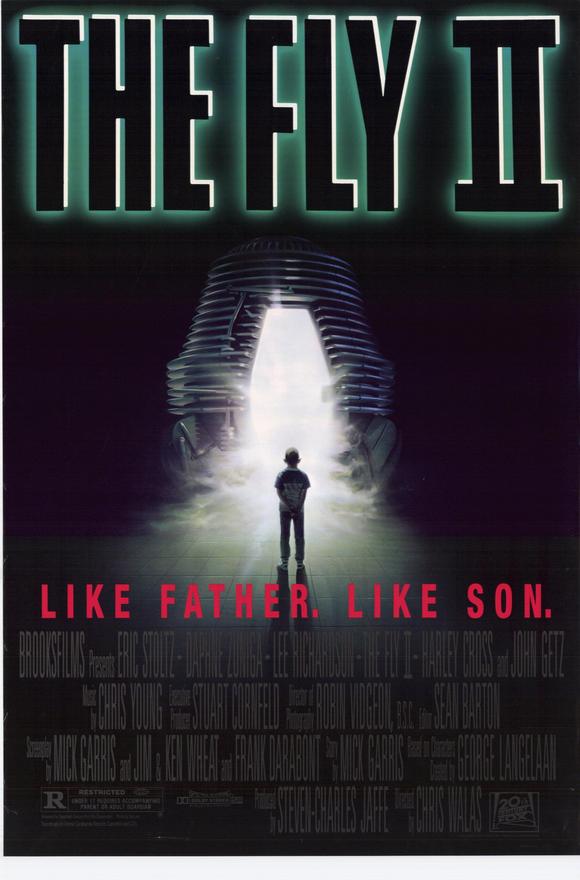

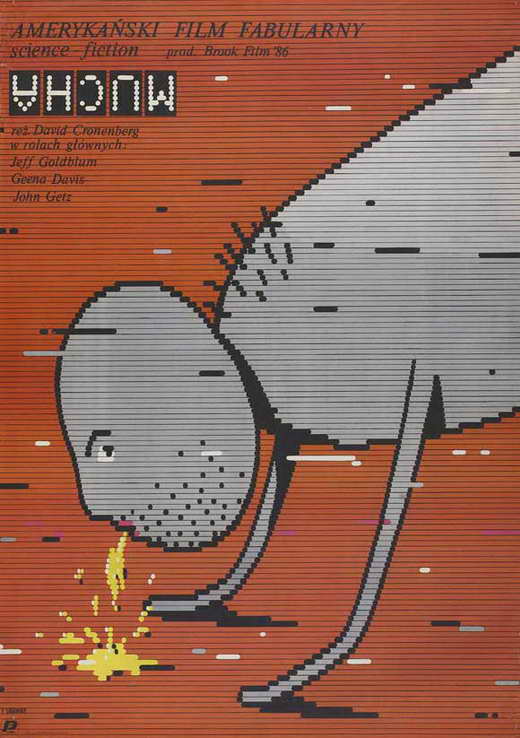

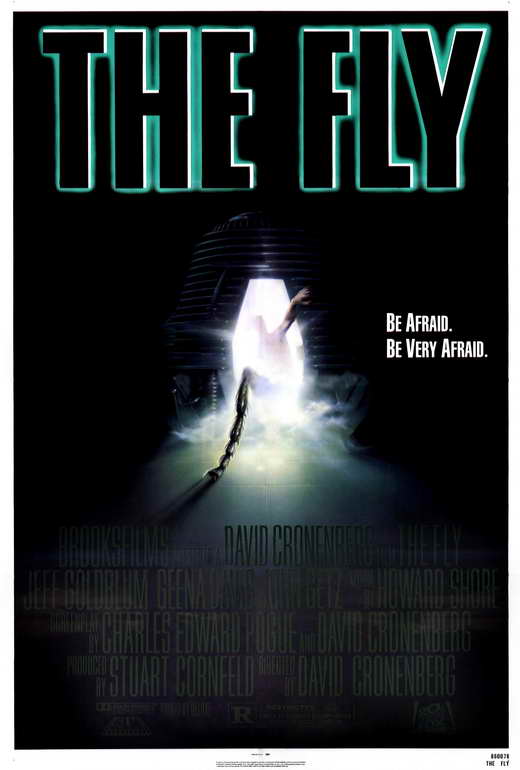

If it had been made in the 1950’s, undoubtedly The Fly II (1989) would have been called “Son of the Fly.” Picking up on the only thread left dangling from David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986), Veronica Quaife (now played by Geena Davis lookalike Saffron Henderson), still carrying Seth Brundle’s child with his fly-corrupted genes, gives birth in a high security facility within the Bartok Company, the financier of Brundle’s telepod experiments. Echoing the nightmare sequence of the first film, her offspring appears to be slime-covered insect larva, and Veronica dies from the delivery. But the sac splits open and a seemingly ordinary baby boy lies within. The audience has to accept that Veronica would not go through with an abortion, which she’d already attempted in The Fly before Brundle kidnapped her – it’s a suspension of disbelief, given her determination to abort the mutant inside her, and the fact that she witnessed her lover’s horrifying deterioration and loss of humanity. But – horror films must have sequels, and here we are. Though Davis does not return, Jeff Goldblum sort of does – in outtake footage from the original film, viewed as video recordings which his son studies. The boy, Martin Brundle (Eric Stoltz, Mask, Pulp Fiction), at first has no outwardly fly-like mutations, but he is obviously “different.” For one thing, he has a superior intelligence. For another, he grows into Eric Stoltz within the first five years of his life. He is raised within the Bartok facility under surrogate father figure and company founder Anton Bartok (Lee Richardson, Prizzi’s Honor), a greedy, soulless megalomaniac. To keep the restless young genius Martin engaged, he offers him a job in the facility: to work on his father’s old telepods, which can no longer successfully teleport human flesh. Martin has already witnessed the horrifying result of Bartok teleporting his beloved golden retriever. Reviewing his father’s tapes, he tries to find the nuance in the programming, inspired by his romance with another Bartok researcher, Beth Logan (Daphne Zuniga, The Sure Thing, Spaceballs). But his experiments take on more urgency when he realizes that his flesh is beginning to transform and reveal the corruption of Brundlefly’s genes.

Young Martin Brundle, growing at an accelerated rate.

As with The Fly, this sequel comes from Mel Brooks’ Brooksfilms. The first treatment was provided by Video Watchdog‘s Tim Lucas, who had a strong relationship with Cronenberg after chronicling the production of Videodrome and The Fly. His idea, which he recounted on his blog last year, would have been called Flies (a la Aliens), with Davis to return as Veronica, now encountering Brundle’s consciousness as a ghost in the machine within the Bartok Company. Brundle’s mind is being exploited by Bartok to create new innovations. Lucas’s treatment went further, introducing the concept of cloning. Despite an endorsement from Cronenberg, the concept was not accepted by Fox, and it was Mick Garris (The Stand) who tackled the project next. (The final version of the film does contain elements from Lucas, notably that it all takes place within the Bartok Company.) In a 2010 interview with Geekscape, Garris recalled that his script “dealt with concepts of birth and abortion, an evolutionary next step in the ‘special’ child of Veronica Quaife and Seth Brundle. Religious fanaticism played a part, and there was a lot going on. But at the time, Leonard Goldberg was running the studio, and Scott Rudin was our production executive. They had contrasting views of how the movie should be done, and I was right in the middle. They wanted to make a teenage horror movie, which was not how I wanted to go.” So the project was handed over to Jim and Ken Wheat (Pitch Black), with a final pass by Frank Darabont (The Mist, The Shawshank Redemption). Despite all the mutations the story underwent, this is not a bad gene pool from which to draw. With Cronenberg off tackling original projects (he was between Dead Ringers and Naked Lunch), directing duties were handed to the creature effects artist of The Fly, Chris Walas. Walas had also worked on Gremlins, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Return of the Jedi, among others, but The Fly II was his first feature film as director. Apart from an episode of Tales from the Crypt, to date he has only directed one other film, The Vagrant (1992) with Bill Paxton.

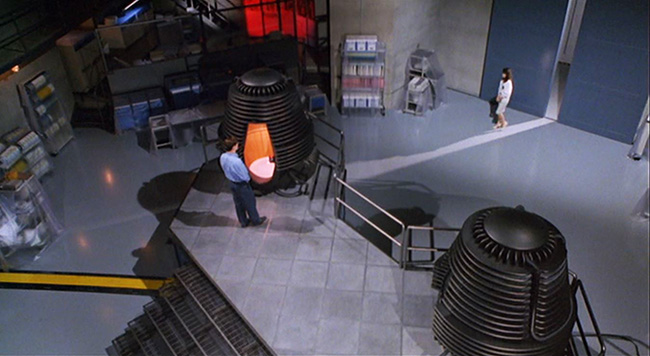

Martin (Eric Stoltz) shows Beth (Daphne Zuniga) the telepods.

The main failure of The Fly II is that it is never all that interesting – not like the unfolding morbid fascination in Cronenberg’s original. It is not, however, a bad film – just a disappointingly ordinary one. Darabont’s screenplay, which seems to incorporate elements of all the writers who had worked on the story before him, does make one smart decision, borrowed from The Fly: building up the characters as long as possible with an extended first act. Although Stoltz’s Martin Brundle has limited depth – after all, he’s only been alive for a short amount of time, and his experiences are few – we’re given plenty of opportunity to develop empathy for him, and the romance he develops with Beth is convincingly handled (Zuniga is a strong actress). One wonders if Stoltz was cast because of his ability to act beneath layers of thick makeup (Mask), though eventually he enters a cocoon state and emerges as a giant puppet not unlike the Queen in Aliens. Before that happens, Martin has to contend with a lecherous security guard and the absurdly sinister Bartok, two-dimensional foes that make the film feel cookie-cutter. When Martin escapes from the facility with Beth, they pay a visit to the first film’s Stathis Borans (John Getz, the only returning cast member), although, in what might be a symptom of the screenplay’s tortured development, he doesn’t contribute anything to the plot, but merely states that Martin already knows the answer to his problem. That answer would be taking a human test subject into the telepod with him to absorb the genetic material and purge the fly out of him, something which will likely kill the other person.

Beth Logan (Daphne Zuniga).

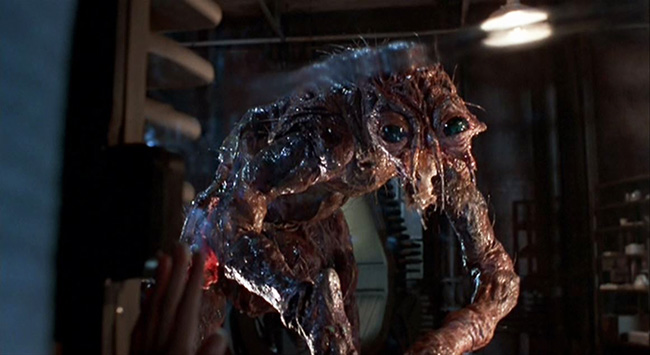

If any of this will stick with you at all, it will probably be Martin’s poor golden retriever, which – he discovers halfway through the film – has been kept alive by Bartok even after being mostly reduced to oatmeal by the telepod. I can’t emphasize this enough: the dog puppet is one pathetic-looking creature, its tongue hanging out, covered with sores, crawling miserably toward its bowl of swill. In a tearful moment, Martin puts it out of its misery. Tearful? Maybe hilarious? Am I sick for laughing quite hard at this scene (and I am a dog owner, I should add)? It would help, perhaps, if the dog didn’t look like someone had run over a Muppet. But this does set the stage for one of the best scenes in the film. In the Alien/Aliens inspired climax, security sends their guard dog chasing down the hallways to find the monster. In a typical horror film, that would spell the end of the dog. Credit to Walas and Darabont for instead having Martinfly lean over and pet the animal – a very nice gag. And now that I think about it, maybe the key difference between The Fly II and its predecessor is that this one has a soft spot. The climax provides deliverance for the hero and justice against the villain (amidst some very effective splatter scenes and gooey makeup effects). Cronenberg’s is more cynical, and therefore more haunting. His film stays with you. The Fly II is a sequel, and seems to be under no obligation to linger in the memory after the credits have ended. But there are much worse ways to kill an hour and a half.