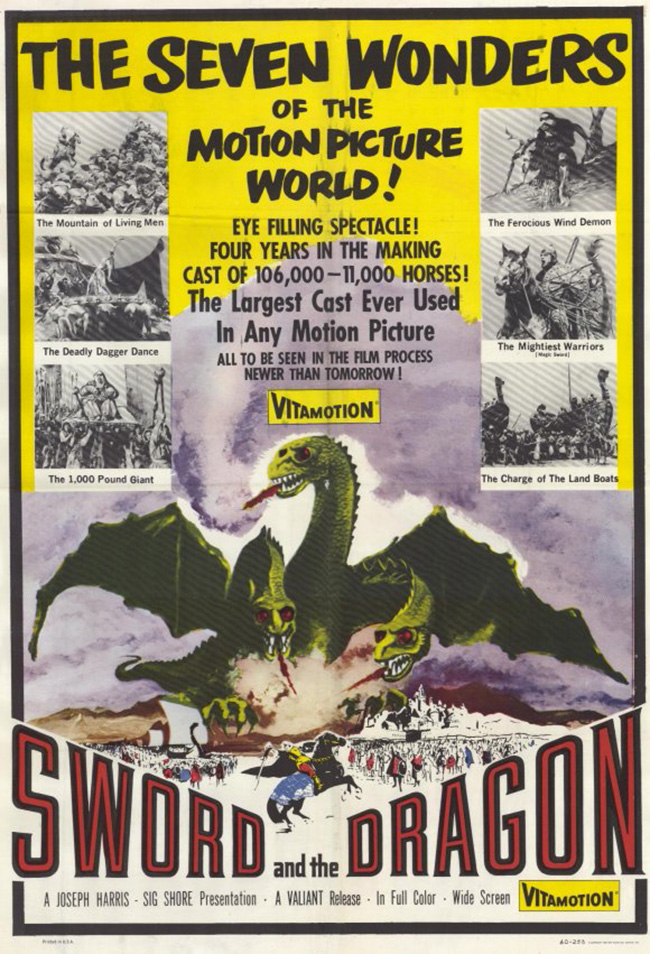

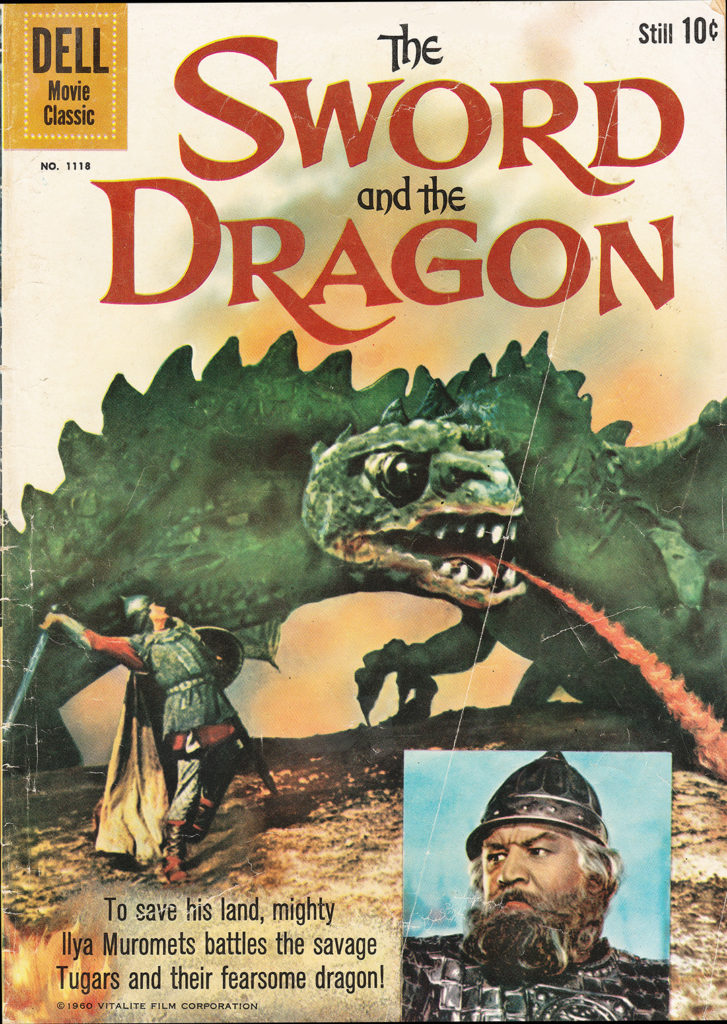

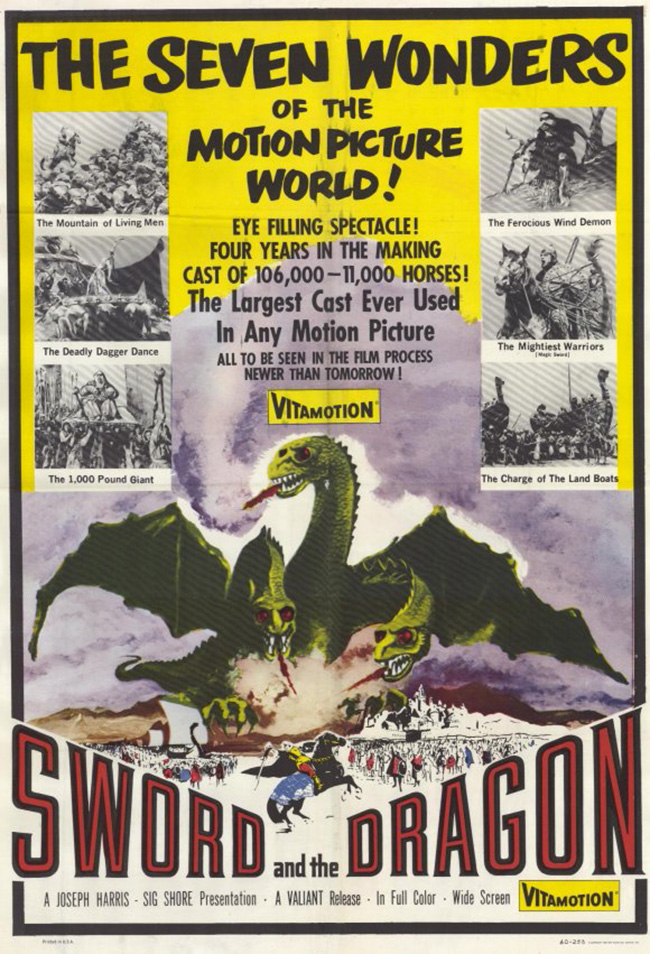

Russian director Aleksandr Ptushko’s Ilya Muromets (1956) is another of his fantasy epics, and rates highly among his considerable body of work for its inventive, nonstop special effects and the grand scope of its production. But, of course, it also became fodder for Mystery Science Theater 3000 in its 1960 English-dubbed edit, The Sword and the Dragon; and so I’m taking a look at this film in the penultimate entry in my series examining the original versions of the Russian films featured on MST3K, in honor of its upcoming Netflix reboot. (See my previous entries on Sampo [The Day the Earth Froze] and Sadko [The Magic Voyage of Sinbad].) This is actually my third time watching Ilya Muromets. As with the other films in this series, I own the Ruscico DVDs, which I collected while researching Russian fairy tales; and I wrote briefly about this film in my global-themed movie marathon Around the World in 24 Hours of Film. This third time around was just as pleasurable as the first two, so I can fairly say I like this movie. It should be noted that the film has a real coherency in its original cut which seems absent from the butchered version featured on MST3K – that is, when I watch that version, I have no idea what’s going on, but in Ptushko’s original, I find myself absorbed. And, as with the other films in this series, the goofiness which played so well to riffing can be better appreciated if you know the background of the folklore. (That doesn’t mean it’s any less goofy, just that it’s not as inexplicable, if you get my drift.)

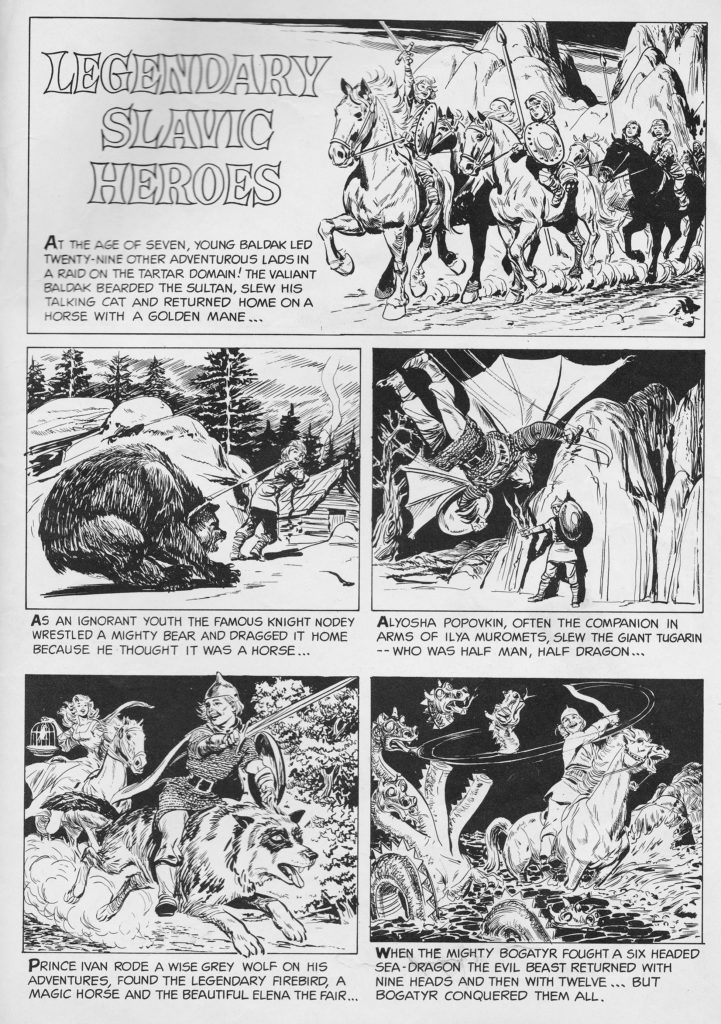

The giant bogatyr (knight) of legend, Svyatagor, offers his fabled sword to travelers to deliver to the man who will carry his mantle – Ilya Muromets.

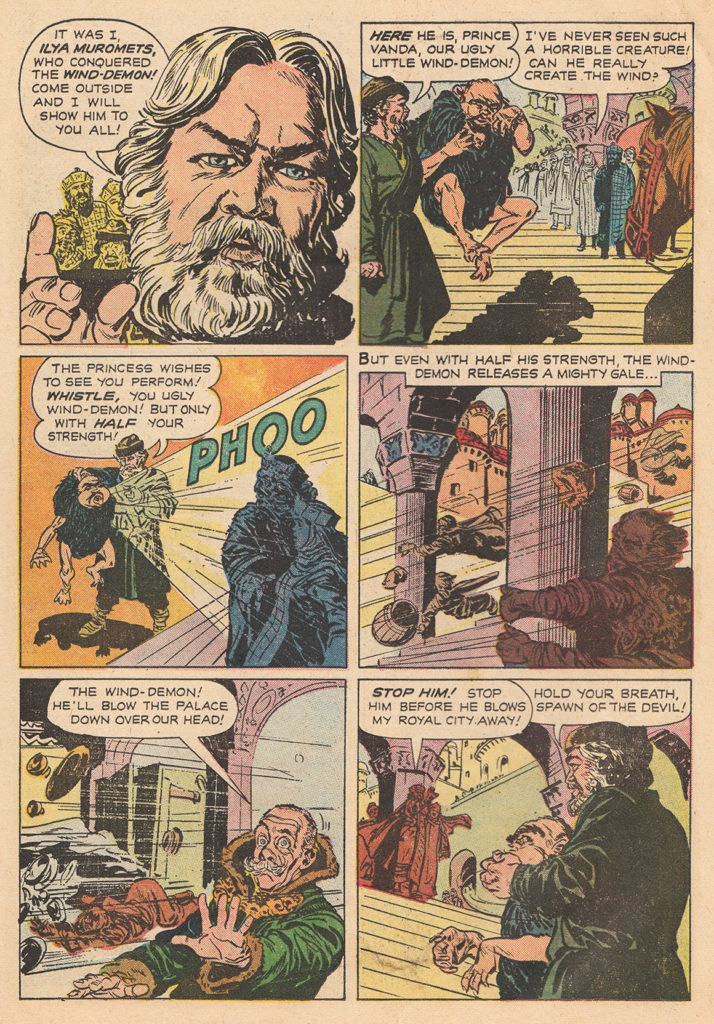

Take, for example, what seems to be the film’s wildest creation, a bird-man who perches in a tree blowing powerful winds at anyone who approaches. As he blows, his prosthetic cheeks inflate like balloons; he has the makeup grotesquery of a villain from Dick Tracy. This is Nightingale the Robber, who is described in the legend of Ilya Muromets exactly as Ptushko portrays him. You can’t fault him – he has a faithfulness to the original fairy tales as exacting as any modern day comic book film must attend to its source material. In the film, the bogatyr (a Russian knight-errant) Ilya (Boris Andreyev) encounters the monstrous Nightingale after being told by disembodied spirits that there are three paths he might take across land. “If you go to the right, you’ll get rich. If you go to the left, you’ll get married. If you go straight ahead, you’ll get killed.” Muromets pragmatically replies, “It’s too early for me to get married, and it’s no use for me to be rich. I’d better go the way to get killed.” Nightingale is on this path, but Ilya conquers him by breaking the tree branch on which the robber is perched. In Kiev, the center of Kievan Rus’, Ilya greets Prince Vladimir (Andrei Abrikosov) with Nightingale in his sack. To prove that his captive is really the robber of legend, he allows Nightingale to blow his “whistle.” The city and palace are subjected to winds of such force that the citizens topple up stairs (reverse photography), banquet tables are cleared, and a basket with a hen and her eggs tumbles over, the eggs immediately hatching into chicks as they continue to tumble through the gale – this is Ptushko at his most delightful, demonstrating his animator’s sensibilities.

Ilya Muromets (Boris Andreyev) holds aloft Nightingale the Robber before Prince Vladimir (Andrei Abrikosov).

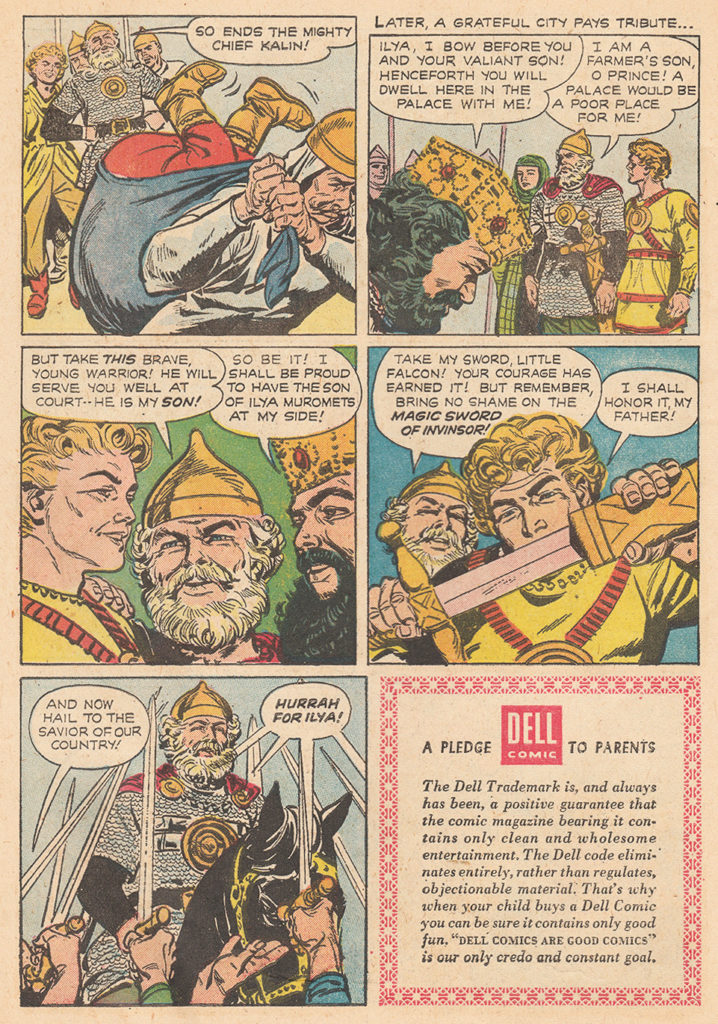

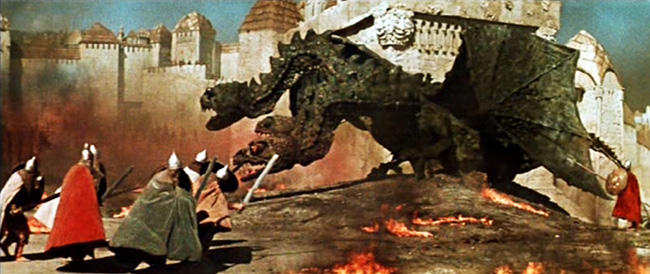

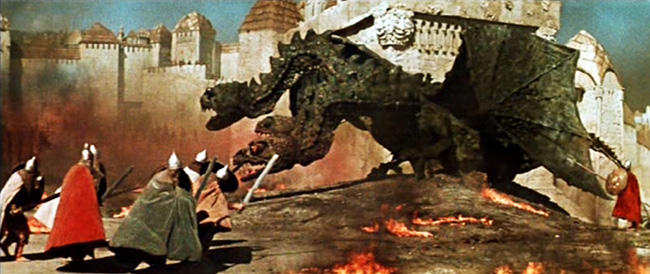

Ilya has come to Kiev to help stop the raids of the Mongolian Tugars. After he arrives, he defends himself against an assault from a Tugar ambassador, portrayed as a corpulent giant borne on the backs of slaves. With the ambassador killed, Ilya becomes Prince Vladimir’s champion. Ilya rescues his lover Vassilisa (Ninel Myshkova), and she bears him a son called Little Falcon. She also creates for him a magical tablecloth which can provide sustenance; while she works the loom, she sings a song with accompaniment by woodland animals (most of them mechanical), like a live action Snow White. But a Tugar spy, Mishatychka (Sergey Martinson), is at work in the court of Prince Vladimir, and he sows doubt in the prince, until the bogatyr is thrown into the dungeon. Mishatychka refuses to feed his prisoner, hoping Ilya starves to death, but in secret Ilya uses his magical tablecloth to keep his strength. Meanwhile, Vassilisa and her son are kidnapped by the leader of the Tugars, Tsar Kalin (Shukur Burkhanov), a Genghis Khan type who subsequently raises Little Falcon to be his own jousting champion. By the time Little Falcon is ten years old, he’s a great warrior who looks like a grown adult, and he faithfully serves Kalin. As Kalin marches his vast army toward Kiev, Prince Vladimir releases Ilya from prison. Ilya is dispatched to Kalin, where he first uses subterfuge to thwart the wicked Tsar, before leading the Kievan armies in an epic battle. To attempt to turn the tide against Ilya’s and Vladimir’s forces, Kalin releases the three-headed dragon of legend, Gorynych, who lands before the castle gates breathing fire upon the soldiers. (Prompting my wife to exclaim, “Why didn’t he just do that in the first place?”)

The three-headed serpent Gorynych.

Everything here is visualized in broad strokes, from the mountain of Russian gold and pearls on which Tsar Kalin sits greedily, to the final battle, in which soldiers are lifted in the air on the points of spears and suspended there. When Kalin wishes to see further down the landscape, he orders his men to pile on top of one another until he can stand tall enough – another mountain for him to climb, this one of human bodies. The emotional lives of the characters are almost nil (par for the course), since they are not so much people as archetypes of legend; the closest we come is the reconciliation between Ilya and his son, though even this occurs after a wrestling match on the battlefield. Ptushko was ideally suited to bring Russian fairy tales and folklore to the screen, because he treats the surface-level stories as lush, colorful spectacle. This was the first Russian widescreen film, and he fills the frame evocatively, such as in Tsar Kalin’s camp, where Kalin watches a girl perform a salacious sword-dance from the sidelines, or in Prince Vladimir’s descent into his dungeons, where a small portion of the screen is lit by his torch before the light floods Ilya’s cavernous chamber. The opening image of the giant Svyatagor, astride his horse and gazing down at his visitors who stand at the edge of a cliff, is typical of Ptushko’s larger than life approach – he is working in the realm of tall tales. Svyatagor, having passed on his sword to Ilya Muromets, fades and becomes a mountain. This is the sort of film where that can happen, and it’s a treat to behold.