There is a Monty Python sketch which only lasts about twenty-five seconds, but that’s all it needs. Stately music plays on the soundtrack. It’s a simple country garden. A businessman enters the scene, pursued by a nude woman. They’re chased by a few more nude women, a British explorer, a Viking, a pantomime goose, and several others. Everyone piles on top of one another in a mass orgy as a title appears onscreen: “Ken Russell’s Gardening Club (1958).”

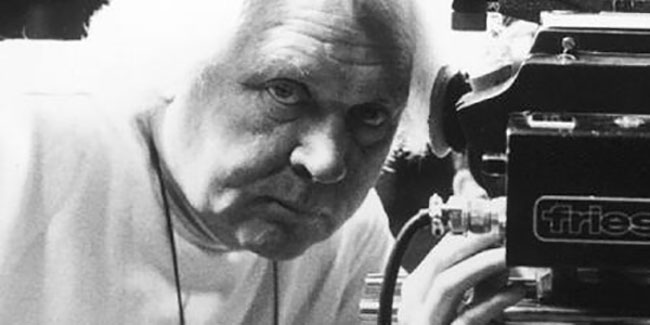

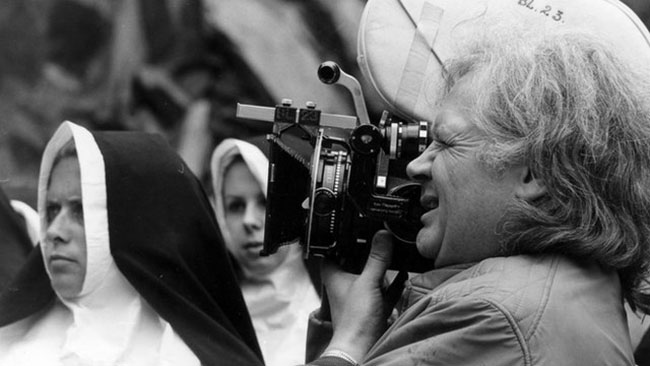

Such was Ken Russell’s notoriety by the early 70’s, and he was just at the start of his career as a feature filmmaker. He’d begun as a photographer, before making short, cutting-edge documentaries for the influential “Free Cinema” movement (1956-1959) launched by Lindsay Anderson (If…). He transitioned into making documentaries for the BBC, but retained the experimental ethos by incorporating dramatizations that were groundbreaking for the time. It was in television that he began assembling what would become a repertory company of recurring players, most notably Oliver Reed, who would become the De Niro to his Scorsese. Increasingly his BBC documentaries began to resemble proper feature films (both in scope and in length), and he continued making them up through 1970 – even after he had launched a major film career. That last BBC film was Dance of the Seven Veils (1970), about Richard Strauss. Russell detested Strauss and his music, and so this is one composer biopic that sets out to damn its subject, condemning the composer’s role in the Nazi regime. The Strauss family complained, and the film was never re-run. But by now Russell was emboldened by success: Women in Love (1969), his sensual big screen adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s novel, was nominated for four Academy Awards, Glenda Jackson winning for Best Actress; it also won the Golden Globe for Best English-Language Foreign Film, and was nominated for eleven BAFTAs.

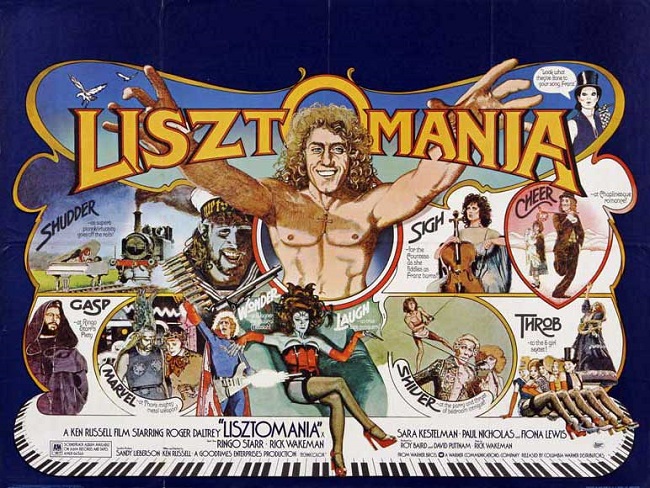

Shortly thereafter Russell plunged headlong into controversy with two envelope-pushing historical dramas, The Music Lovers (1970), a blistering biography of Tchaikovsky with an emphasis on his sex life, and The Devils (1971), with its raving nun orgies, masturbating priests, and extreme violence. The two films seemed to act as a mission statement, and from there began a decade’s worth of flamboyant biopics and surreal musicals, always with a photographer’s impeccable eye, excellent performers, and a sense of dream-like exaggeration that made him England’s answer to Fellini. But though his repertory company dutifully followed him on each adventure, critics largely turned up their noses and dismissed him as a vulgarian. The rock opera Tommy (1975) was nonetheless a big hit at the British box office, as was its follow-up, Lisztomania (1975), and he ultimately earned a ticket to Hollywood where he made the science fiction spectacle Altered States (1980). It was a troubled production only because of his heated, headline-making conflicts with screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky. Russell only made one more film in America, the bitter kiss-off Crimes of Passion (1984) starring Kathleen Turner and Anthony Perkins.

By then, he had already begun refocusing on more comfortable jobs back in England. A deal with Vestron Pictures led to Gothic (1986), The Lair of the White Worm, Salome’s Last Dance (both 1988), and The Rainbow (1989). Here he was given much smaller budgets, and yet continued to produce art that was both unique and indisputably the work of an auteur. After the NC-17 rated Whore (1991), Russell focused on television and short films. He was able to enjoy some belated appreciation for his lengthy career before his death in 2011, but he still remains an acquired taste and continues to be rejected by the critical mainstream. As recently as a few weeks ago a prominent website for film criticism used the name Ken Russell as an insult.

That comment had me turning my attention back to the director’s films. I began to catch up with those I’d missed, and revisited many I’d seen before. In watching so many back to back over the past week, my appreciation for Russell’s passion and artistry has only grown. Programming them together, one after another, makes clear just how focused Russell was on his pet themes and subjects; they become pieces in a much larger puzzle that suggests, despite the arguments of his contemporary critics, that he knew exactly what he was doing. The vast majority of his films are period pictures – Russell had a scholarly interest in the past, and even his most outré films often reveal insightful historical details. Most of his films are biographies, an extension of his BBC work but taken to grand, adults-only splendor. And over and over he depicts the artistic process, diving into the mindscape of geniuses to see what propelled them, dissecting the details of their amour fou – whether they are dancers, sculptors, or, of course, classical composers. Despite choosing subjects that some might consider best suited for a classroom, his films were never stuffy and were always populist.

Here’s the thing: it is a natural critical response to want an artist to do something radically different than what they’ve done in the past. To even change their voice. Wes Anderson does not need to make Francis Ford Coppola movies. Haruki Murakami does not need to write Tom Wolfe novels. Artists are likely to express themselves in their own unique way. They are producing the work that represents them. Ken Russell was always Ken Russell. It is possible to imagine a more “respectable” version of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome than what Russell gives us in Salome’s Last Dance. When Salome delivers her ode to John the Baptist’s body, hair, and mouth, it would be possible to have this not occur as a staged performance by a brothel (for the benefit of an attending Wilde). It would be possible to do this realistically, and not against a painted backdrop; it would be possible to not have Salome flanked by topless women and half-naked gladiators, to not have John the Baptist look like a glam rock star, or even to cast someone other than the very unique, semi-androgynous Imogen Millais-Scott as Salome. One could cast a celebrity in that role, or remove the meta framing device. At the end of the day, I would much rather watch Ken Russell’s version, and Millais-Scott is not just his Salome; now she is my Salome too.

Watch enough Ken Russell, and you begin to learn that he has his own language, his own method of expression. What might at first seem extreme or unusual falls into a lexicon that you begin to understand, and no longer seems quite so vexing. Isn’t this how it is with most artists? Read enough of their books, view enough of their paintings, and you get to know them as people. You begin to see how they see the world.

Therefore, this proposed “24 Hours of Ken Russell” is an attempt at getting to know Ken Russell on his own terms. Admittedly it’s a parlor game, and I didn’t actually view them all in a day. I did, however, watch or rewatch all but three of the thirteen films listed, as well as another film which ultimately wasn’t included. In establishing this order, I was mindful of just how well each film might play at a given hour, and understanding its relation to the films before and after. It is almost, but not quite, a “Best Of.” There are one or two glaring omissions, and at the end you can read my excuses as to why some films have been left out. To more adventurous film buffs interested in a deep dive into the world of Ken Russell, I’d encourage giving this a go, but if that’s too extreme (and it is!), perhaps you’ll find a title that will draw your curiosity and spark a reevaluation of one of the most interesting and daring filmmakers of the 70’s and 80’s.

6am: Isadora: the Biggest Dancer in the World (1966)

Begin the Ken Russell marathon with the letters I-S-A-D-O-R-A spelled out on the screen and screamed out on the soundtrack, followed by a breathless summary of the most sensational aspects of the life of American dancer Isadora Duncan (Vivian Pickles, Harold and Maude) as told in newspaper headlines and with stylized reenactments. Duncan dancing naked on the stage until she’s dragged off; the drowning death of her two children when their runaway car became submerged, the driver still holding the automobile’s crank on the shore; a Russian lover’s suicide by hanging, feet dangling in the air, and so on. Only then does Russell slow down to go through her incredible life at a slightly more restrained pace. But only slightly. This docudrama for British television was one of many Russell directed between 1959 and 1970. His specialty was the biography of a famous artist, composers being a particular obsession. By the time he made Isadora, he’s already begun establishing an auteur’s approach to these biographies, and it had become easy to identify his stamp. Even in cinéma-vérité black-and-white and with a (deliberately) dry narrator, there is no mistaking that this is a Ken Russell film. He bounces off that narration the most passionate images he can conjure, from a giant box filled with harpists gifted to Duncan by her wealthy lover, to a tender choreography between Duncan and her two children which becomes a farewell before their tragic drowning, or an aging Duncan posing for a photographer atop a mountain of pillows (the first of many mountains we will see in this marathon). There is a frenzy in the editing and performances which has become a signature of Russell’s work, and has often been attacked by exhausted critics; but his subjects so often are artists and their creative process – it’s part of the game. In the perpetually dancing Isadora Duncan, Russell finds another apt subject of artistic delirium. The abrupt, violent death of Duncan, from which Russell cuts away to depict a stunning vision of the dancer surrounded by an army of little girls dancing to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” rates as one of the director’s most powerful moments. Also of note is an uncredited cameo by Peter Cook.

Availability: In the US on the DVD set Ken Russell at the BBC, and in the UK as part of The Ken Russell Collection: The Great Passions.

7:15am: Song of Summer (1968)

In contrast to the endless physicality of Isadora Duncan’s artistic expression, this touching biography for the Omnibus TV series catches up with Frederick Delius (Max Adrian, The Music Lovers) in the last years of his life, when the composer was blind and paralyzed as a result of syphilis. Russell mainstay Christopher Gable (Women in Love) plays Eric Fenby – whose 1936 memoir Delius As I Knew Him forms the basis for this drama – a young, church-going English composer who travels to France to stay with Delius and his wife Jelka (Maureen Pryor, The Music Lovers), assisting the atheistic libertine in completing his music. Fenby quickly becomes frustrated with the process, spending most of his time reading novels and newspapers to the prickly composer, and when Delius does begin to dictate, the melody is a harsh “TA-TA-TA-TA.” But the two come to an understanding, as Fenby begins to decipher Delius’ methods, and together they translate written poetry into symphonic music using just a piano and Delius’ lips – his arms stiffly frozen to his sides. Russell ranked this his best work, and he might have been right. Russell constrains himself just as Delius is restrained by his prison of a body, allowing the music to liberate the action – in one notable scene, with a flashback to a journey to a mountain summit for a closer look at the sun. This is a beautiful, inspired work that transcends its TV-movie origins. The cinematographer is Dick Bush, who filmed Isadora Duncan and would go on to work with Russell on Mahler (1974) and Tommy (1975), among others.

Availability: In the US on the DVD set Ken Russell at the BBC, and in the UK as part of The Ken Russell Collection: The Great Composers.

8:40am: The Boy Friend (1971)

“Ken Russell’s Talking Picture The Boy Friend” read the opening titles. It’s easy to forget that the same year Russell gave the world the poison pill of The Devils, he also delivered this old-fashioned, G-rated adaptation of Sandy Wilson’s 1954 musical-comedy set in the 1920’s. It was a natural fit for Russell’s theatricality. Gawky and bespectacled assistant stage manager Polly (Twiggy) is forced to fill in for the lead role in a stage musical when the actress literally breaks her leg. A Hollywood starmaker is in attendance, so stakes are high at this otherwise deserted matinee, as the line blurs between the actors and the characters they play. Russell takes the opportunity to parody elaborate, awkward staging – at times it’s as though the cast are stuck in a malfunctioning It’s a Small World ride, and in one hilarious scene Polly tries to read her lines which are attached to a constantly-in-motion bouquet. But then the cast’s dreams overtake and transcend the confines of the stage, resulting in nostalgia-infused, kaleidoscopic numbers, such as a Busby Berkeley routine staged on a gigantic turntable, or an extended, wordless digression into Greek mythology filmed in a meadow. In one scene, he lets the drop curtain split the screen to contrast the differences between on-stage and backstage action. Also stars Tommy Tune, Vladek Sheybal (From Russia with Love), Bryan Pringle (Brazil), Antonia Ellis (Mahler), Barbara Windsor (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang), and Christopher Gable and Max Adrian from Song of Summer, along with a cameo from Russell muse Glenda Jackson (Women in Love).

Availability: On MOD DVD from Warner Archive, or streaming from Google Play.

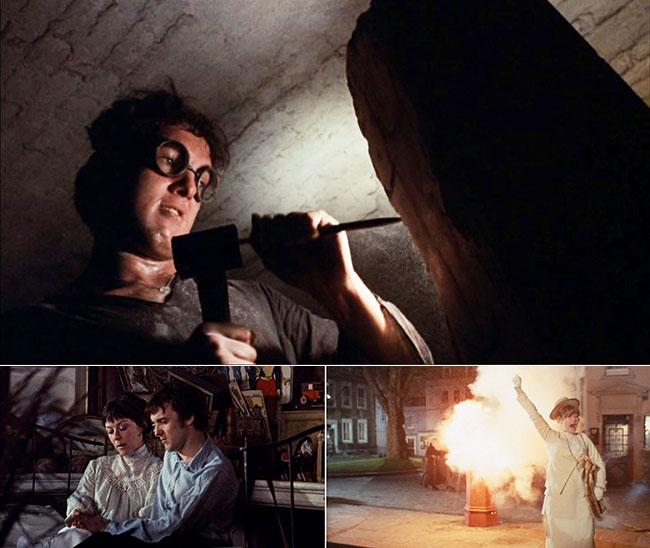

11am: The Music Lovers (1970)

If Russell’s breakthrough was Women in Love (1969), The Music Lovers was the film that established his reputation, for better or worse. His unflinchingly erotic and passionate portrayal of the inner lives of the gay, closeted Tchaikovsky and his sex-starved wife Antonina was too sensationalistic for film critics, while music critics, nitpicking the details, couldn’t disguise their outrage. The lavish, elegant production values only seemed to irritate all the more. “It’s not only trivial, it’s bad, vulgar, woman-stuff,” says one of Tchaikovsky’s rivals, composer Nicholas Rubinstein (Max Adrian again), in the film. The composer (Richard Chamberlain) retorts, “It’s the best I’ve ever written. I will not change one single note!” It’s easy to see why Russell found an apt surrogate in Tchaikovsky. Russell, too, was more interested in the ecstasy of art than bowing to contemporary “good taste.” Yet the film speaks to a trend in early 70’s cinema to push all kinds of boundaries; in many ways, Russell was the British equivalent of New Hollywood. (The British film industry was in straits in the 70’s. Russell’s grand and often explicit spectacles were among the few bright spots.) Chamberlain – who was also in the closet at the time – gives an outstanding performance, even playing the piano himself: one of the best special effects in the film is actually seeing an actor and his hands on the keys in the same shot. Glenda Jackson is just as fully committed, as she follows her love for Tchaikovsky into heartbreak, promiscuity, and finally madness. Russell means to break his composers free from the highbrow in their stuffy conservatories, recreating them as human beings, and typically he uses the music itself to guide him: The Music Lovers features one montage after another set to Tchaikovsky’s music while Russell demonstrates the characters’ emotions purely through images. But as the film progresses toward its disturbing conclusion, he loses himself in the manic depression of Chamberlain and Jackson – and you either go along with him or you don’t. (Take, for example, that very “bad taste” shot when Chamberlain, during a queasy, drunken train ride and a failed attempt at consummating the marriage, gazes with terror into the Freudian tunnel of Jackson’s hoop skirt!) The lacerating, grotesque finale wouldn’t be out of place in a Paul Verhoeven film, but audiences of 1970 weren’t ready for that. Pay particular attention to Russell’s use of widescreen. His sweeping camera is constantly reorganizing the mise en scène, telling two or three different stories in a single camera movement, particularly in the early passages, when he has so many characters and relationships to establish. He remains in control of the image as the actors hit their marks – it’s filmmaking as dance choreography. The music was conducted by André Previn, with cinematography by Douglas Slocombe (Raiders of the Lost Ark).

Availability: The Music Lovers, one of the most controversial films of the 70’s, is relegated to an MGM burn-on-demand DVD-R. At least the transfer looks pretty good. It’s also available for streaming on Amazon and FilmStruck.

1:15pm: Tommy (1975)

Russell was a natural choice to bring The Who’s 1969 rock opera concept album Tommy to celluloid (performing the entirety of the album live had become a regular part of The Who’s live act, and ’72 and ’73 saw a stage version with the London Symphony Orchestra and a full cast). The bizarre story of “deaf, dumb, and blind kid” Tommy (Roger Daltrey), who rises from tragic circumstance to become a pinball wizard and finally a pop culture messiah, was perfectly suited for Russell’s surreal, hypersexualized tableaus, which become a feature-length music video – a precursor to Alan Parker’s film of Pink Floyd: The Wall (1982). One strange sight after another unspools on the screen, from an Eric Clapton-led church that worships Marilyn Monroe (with Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon backing him up), to the heroin-injecting iron maiden to which Tommy is subjected, to Tommy’s mother (Ann-Margret) rolling around in baked beans that explode from a TV set. Note that in the climax of the film, Russell recreates a key sequence in Song of Summer, as Tommy (blind, like Delius) reaches apotheosis by climbing a mountain to behold the sun. Such was the emphasis on the soundtrack that the film featured an innovation: “quintaphonic” sound (five speakers, including three behind the screen). The cast of ringers includes Tina Turner (as the Acid Queen), Elton John (as the Pinball Wizard), Jack Nicholson (as The Specialist), and Oliver Reed (as Tommy’s stepfather). The film was a huge hit in England, running for months and giving Russell’s career a much-needed boost. One thing everyone across the board can agree upon: the surreal pinball championship bout of “Pinball Wizard” with Elton John and The Who is pretty damn great. Also great: the “Sally Simpson” song, with Russell’s daughter (and future movie costume designer) Victoria Russell as Sally Simpson, world’s biggest Tommy fan.

Availability: Blu-Ray (with recreated quintaphonic sound) and Amazon Video, Google Play, and Vudu streaming.

3:15pm: The Rainbow (1989)

By the end of this run you may notice the absence of Women in Love. I’ve substituted a different D.H. Lawrence adaptation instead, one that’s been overlooked but is equally worthy of attention. Oddly coming just a year after a BBC miniseries adaptation of the same novel, Russell’s interpretation of The Rainbow – actually a prequel to Women in Love – chronicles the coming of age of the fiery and independent Ursula Brangwen (Sammi Davis, of Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm), a young Welsh girl who falls into a lesbian relationship with her swimming coach, the outright sexual predator Winifred Inger (Amanda Donohoe, also carried over from Lair of the White Worm). But she learns some valuable lessons of survival in a harsh world from Winifred, and applies them when she takes a job as a schoolteacher, coming into conflict with both unruly schoolchildren and a sexually harassing headmaster (Jim Carter, Downton Abbey). Her restlessness and dissatisfaction with what the world has to offer puts her into conflict with the man whom society would intend that she marry. An older Ursula is played by Jennie Linden in Women in Love, and that film’s Glenda Jackson here plays Ursula’s mother (Christopher Gable plays her father). Note a few recurring themes: another symbolic mountain climb (this time in pursuit of an illusion – a rock that looks like a lion and a lamb, but only from the distance), and a love scene in the presence of a waterfall, which is how Tommy opens. This film was one of a number of films Russell made for Vestron Pictures after his early-80’s struggle and fallout with Hollywood. It’s a lovely costume drama, modest in scope but extremely sensual. Russell’s flair for erotic symbolism is in sync with Lawrence’s, as in a scene in which Ursula is pursued through misty woods by a stampede of horses. Another highlight is Ursula finally conquering her classroom – by beating the living shit out of a little bully. With excellent performances by Davis, Donohoe, Gable, and Jackson, as well as a welcome part for David Hemmings (Blow-Up) as Ursula’s uncle, who makes his brutal coin on the backs of coal miners. Clearly a personal project for Russell, it’s further evidence that he could keep his taste for the outrageous in check to best suit the material.

Availability: Streaming on Amazon Video, Google Play, Vudu, and Epix, and there is a Region 2 DVD.

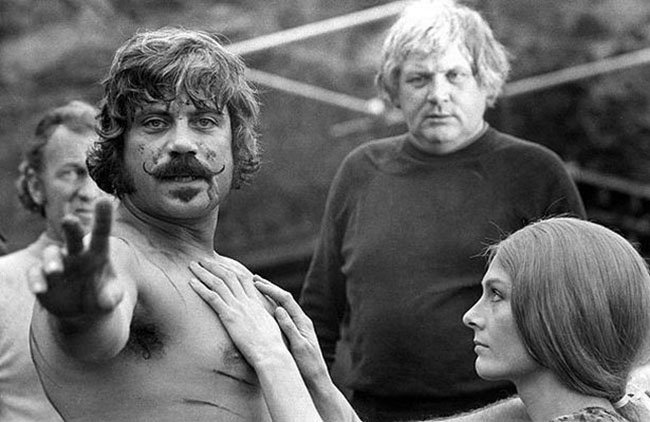

5:15pm Savage Messiah (1972)

Savage Messiah is the overlooked masterpiece in Russell’s oeuvre; I also rate it as one of the best films of the 70’s. In tackling the short, passionate life of French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915), Russell accomplishes his greatest depiction of an artist’s process and point of view: as in a scene when the sculptor (Scott Antony, Dead Cert) stands astride a small mountain of blocks and declares, “Enough stone for at least a fortnight,” all the world is just material waiting to be carved into shape. Russell’s sculptor is young, naïve, arrogant, and exuberant, all ideals and empty pockets. He falls in love with the much older Polish writer Sophie Brzeska (Dorothy Tutin, Cromwell), who has to finally cave to his rationale that society’s opinions don’t matter – passion and art are everything. Mirren plays the spitfire suffragette and life-model that gets between them. Russell stages scenes with the theatrical energy of a musical; it just so happens that nobody ever bursts into song. Yet there is a maturity on display, too, with a muted finale that extinguishes the artist’s flame with barely a wisp of smoke; the abruptness is every bit as shocking as the sudden and violent finale of his earlier Isadora Duncan. For tour de force Russell moments, few can rival the long night Gaudier-Brzeska spends starting and finishing a sculpture on an absurdly rushed deadline, talking breathlessly, his energy never flagging, while his crew of moral support – Sophie and their friend Angus Corky (Lindsay Kemp, The Wicker Man) – gradually fall asleep. I’ve never seen a better representation of the obsessiveness of the creative process on film, with the possible exception of Man on Wire (2008). Also starring Michael Gough (Women in Love), John Justin (The Thief of Bagdad), and Peter Vaughan (Brazil).

Availability: Warner Archive MOD DVD, or streaming on Google Play and Vudu.

7pm The Devils (1971)

Here is a work that burns with hellfire, so difficult to approach that its availability has been severely limited over the decades, with only a somewhat recent UK DVD release to its name. The one-two punch of The Music Lovers and The Devils (1971), both reveling in excess and “vulgarity,” earned the director the reputation of a hellion which followed him for the rest of his career. Though one could argue whether his approach was necessary for a biography of Tchaikovsky, the hysteria, obscenity, and blasphemous imagery of The Devils is indisputably appropriate. The story is rooted in a play by John Whiting and a novel (The Devils of Loudun) by Aldous Huxley, itself based on a true incident in Loudun, France, in 1634. Oliver Reed turns in one of his most vital performances as Father Urbain Grandier, whose unchaste lifestyle and rising influence bring him into the crosshairs of Cardinal Richelieu and the Church. Vanessa Redgrave is astonishing as the depraved Mother Superior Sister Jeanne, who orchestrates a fake mass possession of nuns to point the finger at Grandier as the devilish instigator. The Devils is a fiendish film, full of outrageous and genuinely disturbing images, including its notorious (and once-censored) orgy-in-the-convent. But it’s also a film of righteous outrage that’s aimed squarely at the hypocrisy of the Church, with Reed’s decadent Father Grandier punished to such an unbalanced extreme that he ultimately comes across as an ironic martyr, even a saint. It is a great film, but not an easy one to watch.

Availability: On DVD in the U.K. Nothing but bootlegs in the U.S. – one can only hope that the timid Warner would license it to Criterion.

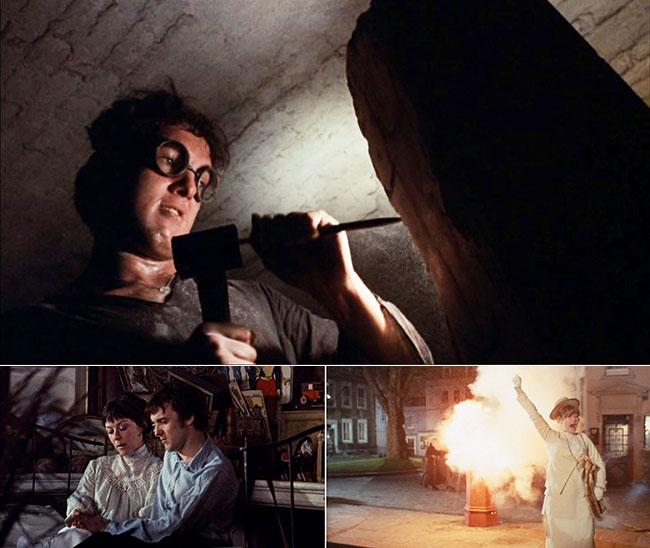

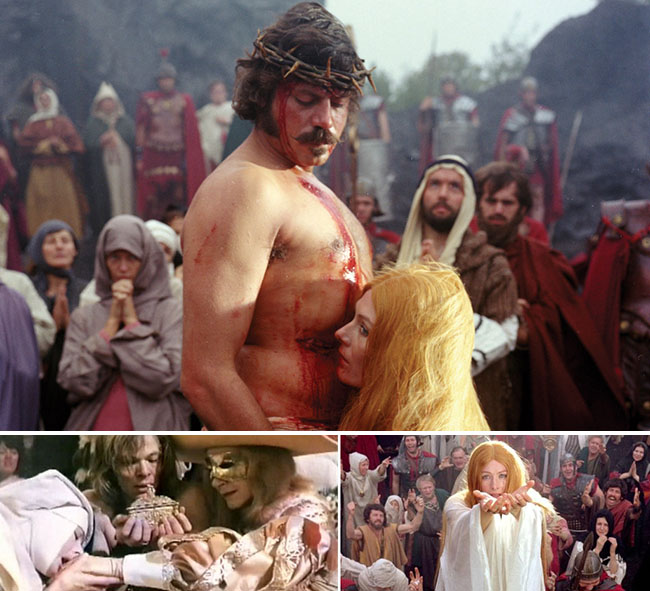

9pm Salome’s Last Dance (1988)

After the gut-punch that is The Devils, it’s time for a bit of a breather as we retire with Oscar Wilde to a Westminster brothel for a performance by prostitutes and servants of his banned play Salome. But make no mistake, this isn’t Russell slouching: it’s actually one of his very best films, both provoking and oddly bittersweet. Modest in scale – made for Vestron Pictures during his post-Hollywood, low-budget downturn – Salome’s Last Dance relies largely upon Wilde’s original play, which was written in French and is translated here by Vivian Russell. The meta-conceit is that we watch Wilde (Nickolas Grace, Tom & Viv) watching the play, with his lover Lord Alfred Douglas, or “Bosey” (Douglas Hodge, Vanity Fair), playing John the Baptist. The shy, Cockney maid, Rose (Imogen Millais-Scott, Little Dorrit), undergoes an astonishing transformation to become the Princess Salome, who desires John the Baptist, and pleads to her stepfather Herod the Tetrarch (Stratford Johns, The Lair of the White Worm) for the prophet’s head, to the delight of her mother the Queen (Glenda Jackson, making yet another appearance in this marathon, and scarcely better). Millais-Scott purrs, “Who is the Son of Man? Is he as beautiful as you, John the Baptist?” She is both lovely and androgynous, looking like a chandelier, or an Aubrey Beardsley drawing brought to life (his Salome illustrations become the opening titles). In her extended monologue to John the Baptist, where she is continually rebuffed, she turns up the charm to the strains of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade: “There is nothing in the world as red as your mouth. Let me kiss your mouth. I will kiss your mouth, John the Baptist. I will kiss your mouth.” (Satie’s Gymnopédie No.1 is also put to very effective use as Herod and Salome negotiate.) Eventually Salome performs her notorious Dance of the Seven Veils, with Russell swapping out Millais-Scott with a man, then both of them taking the stage at once in sexual confusion before the eyes of the drunken, lusting Herod. It’s a scene so spectacular that even Russell himself puts in an appearance to snap a photo. Millais-Scott did not make many films, and this was her last, making it all the more special (for more info, see Judy Berman’s fantastic tribute, Imogen Millais-Scott’s Last Dance).

Availability: Streaming (cropped, unfortunately) on Amazon Video, Vudu, and Epix, and there is a Region 2 DVD.

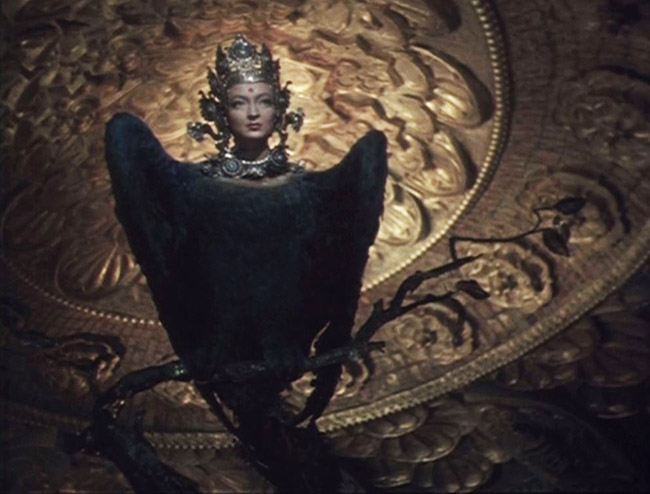

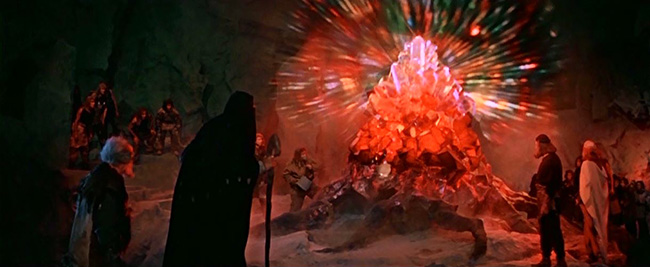

10:45pm The Lair of the White Worm (1988)

“Your entire nervous system is paralyzed,” says Lady Sylvia Marsh (Amanda Donohoe, The Rainbow) to the Boy Scout she has sitting dead-eyed in her hot tub. She’s wearing a thong, thigh-high leather boots, and smoking casually. “You’re a vegetable. Metaphorically speaking, of course. The god is not a vegetarian.” The Lair of the White Worm is based on an obscure Gothic mystery novel by Bram Stoker about an ancient worm of legend that terrorizes the modern English countryside. Although a loose adaptation, Russell’s low-budget film for Vestron takes the strange ideas of its source seriously, which naturally allows a black comedy to take shape. All he has to do is allow Donohoe to vamp it up, and throw in a couple of avant-garde, religious-themed hallucinations to tie the White Worm to the snake from the Garden of Eden. The stuffy British protagonists pitted against Marsh include the future Doctor Who Peter Capaldi, Hugh Grant, Catherine Oxenberg (Dynasty), and Sammi Davis (The Rainbow). A large skull like a dragon’s is unearthed, drawing the attention – and reverence – of the mysterious Marsh. She steals the skull from Scottish archaeology student Angus (Capaldi), but not before spitting venom on a crucifix hanging on the wall. High in a mountain cave (yes, there’s another mountain climb) Angus and his friends discover evidence that the ancient d’Ampton Worm is real and on the hunt, and begin to zero in on a sinister plot by Marsh. The final act of the film builds to a crescendo of black comedy and campy horror. It’s like an art house Fright Night.

Availability: A special features-packed Blu-Ray is due Jan. 31 as part of the Vestron Video Collector’s Series. Otherwise it is available on DVD and streaming on Amazon Video, Vudu, and Google Play.

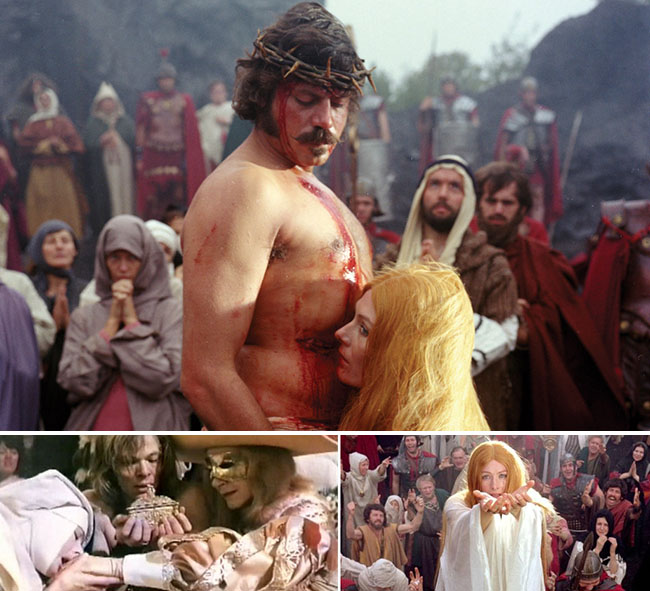

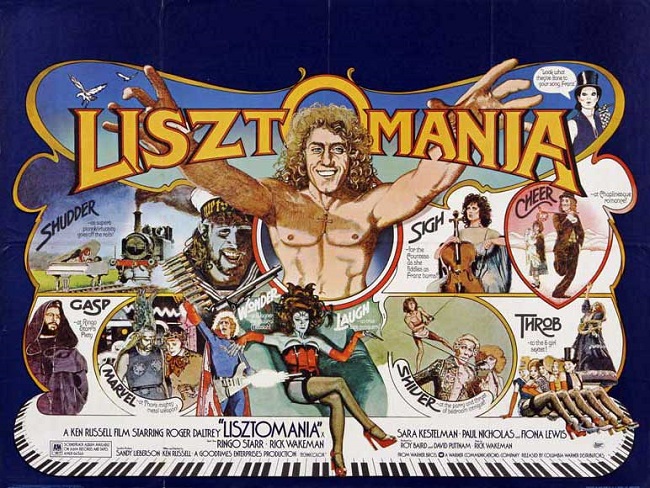

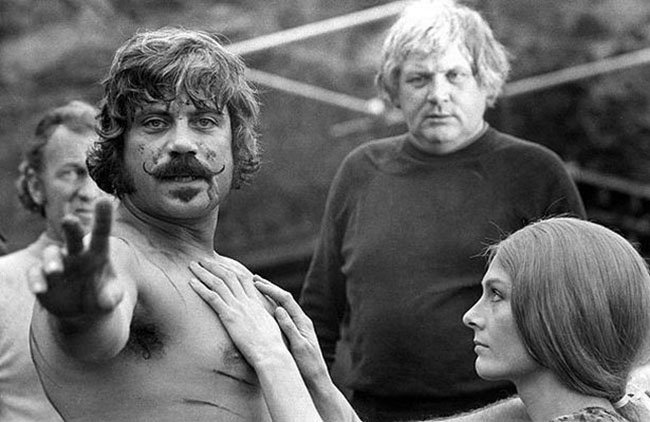

12:30am Lisztomania (1975)

Not just the title of a song by Sofia Coppola’s favorite band Phoenix, Lisztomania is Russell’s fast follower to Tommy, again featuring The Who’s Roger Daltrey in the lead (as Franz Liszt), with music by prog rocker Rick Wakeman of Yes. It’s the most fanciful – and ridiculous – of Russell’s composer biopics, an instant midnight movie with one excessive setpiece come galloping after another, such as when Liszt straddles a gigantic penis which he rides above a number of spread-legged maidens in the court of Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Sara Kestelman, Zardoz), or the opening film’s piano concerto, which Russell presents as a rock concert stuffed with groupies. Ringo Starr plays the Pope, rolling in on his papal throne while Liszt is in bed with a nude woman (Rocky Horror’s Little Nell). From my 2012 review: “Historically inaccurate: Liszt never tried to exorcise a vampiric Wagner, here seen plotting to create an army of supermen (in both the Nietzsche and D.C. Comics meaning) from his Gothic castle, and becoming reborn as a Frankenstein Hitler. That never happened. It is also unlikely that Liszt was ever locked in a chamber by a Russian (Russell favorite Oliver Reed, in a cameo) and nearly suffocated by stone asses in the walls jetting toxic fumes.” But who cares about historical accuracy when there’s this much glitter? You may ask, is this bloated, adults-only, carnival ride of a movie any fun? Hell yes. And it’s essential.

Availability: On MOD DVD from Warner Archive, or streaming on Amazon Video, Google Play, and Vudu.

2:15am Gothic (1986)

“Conjure up all your ghosts!” urges the libertine Lord Byron (Gabriel Byrne, Miller’s Crossing) to his guests: Percy Bysshe Shelley (Julian Sands, A Room with a View), his lover Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Natasha Richardson, The Handmaid’s Tale), her stepsister Claire Clairmont (Myriam Cyr, I Shot Andy Warhol), and doctor and author John William Polidori (Timothy Spall, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban). During their debauched retreat in the summer of 1816, they seek to not only write ghost stories, but actually create a ghost. Famously, the outing will give birth to Frankenstein, but also to a collection of supernatural tales by Lord Byron and Polidori’s seminal “The Vampyre.” The pronouncement-laden screenplay by Stephen Volk (The Guardian) feels like it’s gone through the blender a few times, and the score by Thomas Dolby of “She Blinded Me with Science” fame sometimes crashes jarringly against the action, while Russell seems more interested in wild experimentation than coherency – making this one of his most chaotic, delirious, and strangest films. It’s a mixed bag, to be sure. Biographical details of the famous poets and writers are intermingled with surreal visions, opium-induced hallucinations, and dreams, such as a snake wrapped around a suit of armor, a fish gasping in an emptied bird bath, nipples that become eyes, and a miniature devil crouching on Richardson to recreate the 1781 painting The Nightmare. A Turkish automaton does a striptease; Percy Shelley stands naked on the rooftop in worship of the power of lightning; a pig’s head turns into a severed head; Spall becomes a vampire; Russell runs the film backward; and on and on. The central problem is that the characters and their relationships aren’t properly established, which is a problem when you’re asked to care about Claire’s pregnancy with Lord Byron’s child and the subsequent fallout. For a plot in which characters spiral into madness in a long, dark night of the soul, it would help if events began at a baseline normal. But it is indeed a Gothic, with, at one point, Byrne wandering through his cobweb-draped wine cellar looking for all the world like Vincent Price in a Roger Corman Poe adaptation. And if the film is judged purely on its ability to evoke the logic of dreams and nightmares, then it is a success.

Availability: Stream it on Amazon to see it in widescreen; the Artisan DVD is pan-and-scan.

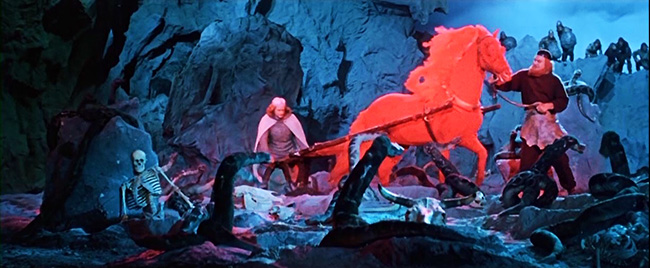

3:45am Mahler (1974)

Our final Russell film to complete the 24 hour cycle is another composer biography, but one about trying to come to peace with life and its meaning (or meaninglessness) on the precipice of death. A cabin on the water explodes into flames. A rock like a man’s face gazes upon a chrysalis which begins to resolve itself into the shape of a writhing woman wrapped in gauze. It’s all a dream of Gustav Mahler (Robert Powell, Tommy), traveling on a train to Vienna and in ill health, accompanied by his wife Alma (Georgina Hale, The Devils) long after their marriage has gone sour. Mahler is one of Russell’s purest portraits of a composer’s life. It’s evident that his budget is smaller than the lavish The Music Lovers, but he enlivens his biography with a timeline that skips back and forth through Mahler’s life using the train journey as a framing device, periodically entering his daydreams and reveries, allowing for Russell’s signature surrealism – such as a dream of Mahler encased in a coffin that resembles a metronome, attending his own funeral and Holocaust-style cremation at the hands of the Nazis to come. Russell also includes sweeping helicopter shots over an Austrian lake and mountains to capture Mahler’s attempts to portray nature through composition. Those who were disappointed by The Music Lovers’ fixation on Tchaikovsky’s sex life might find more satisfaction here, as Russell balances personal details (including struggles with Austrian and German anti-semitism) with insights into his creative method. It also includes musings on the meaning of life: “If I could tell you the answer in words,” Mahler says, “there would be no need for me to write music.” In one of the more outrageous moments – an interpretation of Mahler’s conversion to Catholicism to secure the post of director of the Vienna Court Opera – the composer becomes another of Russell’s mountain-climbers, bearing a Star of David to sacrifice it at the summit, slay a dragon, and eat pork from a pig’s head at the behest of Cosima Wagner (Antonia Ellis, The Boy Friend), dressed up as an SS officer/dominatrix/Valkyrie. It’s a scene that evokes not just Wagner’s Siegfried but also the Fritz Lang silent film. (The character of Cosima last appeared in our marathon in Lisztomania.) I initially saw part of Mahler while flipping channels in the early morning hours a long time ago, and all I could think was Wow – who made THIS? Co-starring singer Dana Gillespie (The Lost Continent), Richard Morant (The Company of Wolves), Peter Eyre (Dragonslayer), and David Collings (Scrooge). A fitting capper to our marathon, equal parts outrageousness, tragedy, humanity, and a note of optimism and youthful exuberance in defiance of death: “We will live forever!”

Availability: On Region 2 DVD.

What didn’t make the cut:

Billion Dollar Brain (1967) is a Michael Caine/Harry Palmer spy movie, well made and entertaining. Russell’s personality is nowhere to be found, however – he was simply cutting his teeth as a feature film director.

Women in Love (1969) is a sumptuous D.H. Lawrence adaptation, with then-groundbreaking male nudity and homoeroticism, an empathetic performance by Glenda Jackson, gorgeous cinematography by Billy Williams (Gandhi), and a boldly understated finale. It has been left off this marathon only to make room for the underseen Lawrence adaptation The Rainbow, but it is nonetheless recommended. It’s recently been released on Blu-Ray in Region 2, and is out on DVD in Region 1. Expect a more in-depth review on this website soon.

Valentino (1977), now available on Blu-Ray, is an epic evaluation of the life of Rudolph Valentino starring the dancer Rudolf Nureyev. There are some memorable sequences – Russell, as ever, gives the film a unique energy to suit its Jazz Age setting – but the prolonged, downbeat climax is more exhausting than satisfying.

Altered States (1980) is an important chapter in Russell’s career, his foray into Hollywood filmmaking. Clashes with Paddy Chayefsky left Russell bruised and frustrated, though the film itself, about experiments with an isolation tank, is an interesting entry in post-Star Wars special effects extravaganzas – one that melds FX with New Age mysticism. It was on this list until I decided to swap it with Gothic. Altered States is the better film, but Gothic is more loose and personal.

Crimes of Passion (1984), his second and final film made in America, is by contrast modest, experimental, thorny, sexually graphic, and completely a Ken Russell film. Katherine Turner and Anthony Perkins turn in feverish performances as a prostitute and the man dressed as a priest who stalks her. I recently reviewed it here, which is partly why I excluded it, though it’s also flawed, challenging, and certainly not for everyone.

Whore (1991), starring Nicolas Roeg favorite Theresa Russell and rated NC-17, is a film that I admit is still on my “must get around to watching” list. I have seen bits of it – and, like Crimes of Passion, it seems to be another gritty, explicit, challenging viewing experience. A review may turn up on this website in the future.

In addition, Russell made a number of TV movies, short films, and docudramas, including contributions to the anthology films Aria (1987) and Trapped Ashes (2006).