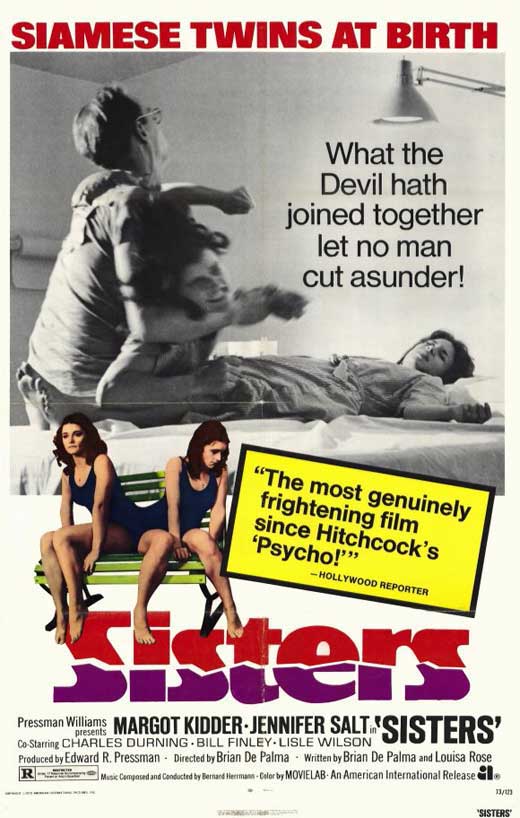

That Brian De Palma is the son of a surgeon – a philandering surgeon, no less, and one who let his son witness his surgeries – doubtless played a role in the development of his stylistic breakthrough Sisters (1973). The film is a psychosexual and Freudian minefield, but De Palma shoves us through it with demented glee. It’s a comedy disguised as a horror film, or a horror film disguised as a drama, or a Hitchcock homage that follows the Master’s ideas to their most absurd ends. It is De Palma adopting the visual language of Hitchcock to advance his voyeuristic storytelling, and now stands out as the director’s maturation into the artist we all know for his meticulous thrillers to come. To seal the connection with Hitch, Bernard Herrmann (North by Northwest, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho, Vertigo) is along for the ride as composer. Sisters also features a virtuoso performance by Margot Kidder, who would move onto another classic horror film, Black Christmas (1974), before enjoying commercial stardom as Lois Lane in Superman (1978). William Finley, who gained a cult following for playing Winslow Leach – the Phantom – in De Palma’s next film, Phantom of the Paradise (1974), had collaborated with the director for many years, but here appears in one of his most significant roles. Sisters also features memorable turns by Charles Durning (The Fury), Jennifer Salt (Hi, Mom!, Brewster McCloud, Play it Again, Sam), and journeyman actor Lisle Wilson (The Incredible Melting Man), who, judging by his performance here, deserved a much bigger career in film.

Phillip (Lisle Wilson) delivers a birthday cake to Danielle (Margot Kidder). Or is it Dominique?

Wilson plays Phillip Woode, who, in the opening scene, has stumbled across a blind woman (Kidder) undressing in his locker room. She doesn’t see him, and he can simply watch. It’s a classic De Palma moment of voyeuristic choice, except even in this early a film in his career, he’s already sending it up: it’s quickly revealed that Woode is in a pre-taped segment for a game show called “Peeping Toms,” and contestants must wager whether he will stay and watch the woman undress or act the gentleman and walk away. It’s a moral dilemma commodified. Woode walks, and both contestants lose, having bet for carnal desire. But for being an unwitting participant in the show, Woode wins a gift certificate to an Africa-themed restaurant (he chuckles at the casually racist gesture; he’s African-American), and invites along the actress model who duped him. Her name is Danielle, she’s not really blind, and she’s recently arrived in New York, a French-Canadian. Kidder pulls off the French-Canadian accent with great charm. Her character was written to be Swedish, but she had grown up around French-Canadians, and suggested to her boyfriend De Palma that Danielle have a French accent instead. He acquiesced to the decision; after all, he had written the screenplay for Kidder as a Christmas present. If you weren’t familiar with the actress from her bigger roles to come, it would be easy to believe that Danielle’s voice were her own. During the date, only gradually does Woode become aware of some slightly disturbing developments, such as Danielle arguing heatedly with her unseen twin sister Dominique (Kidder again), or the fact that she is followed wherever she goes by her French-Canadian ex-husband (Finley, looking uncannily like John Waters). Woode loses her ex-husband, and watches Danielle undress without, this time, looking away – he has stepped out of the reality show and into the fantasy, a theme that would continue through films like Body Double (1984). In the morning, on a whim, he decides to buy a birthday cake for the twin sisters. On the way out, he accidentally knocks Danielle’s pills down the sink’s drain. Danielle frantically tries to find them. When he returns with the birthday cake, he finds Dominique in Danielle’s bed – and he’s stabbed with the kitchen knife that he’d brought to slice the cake.

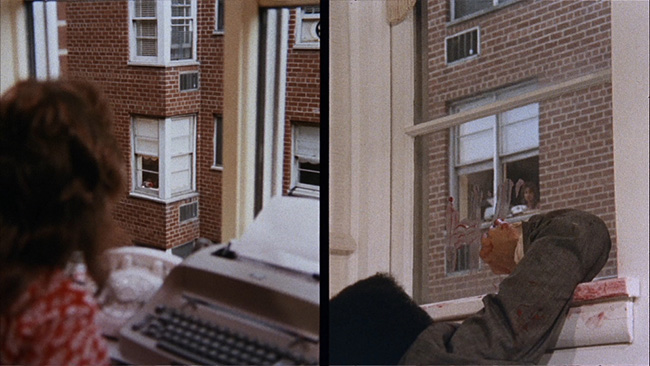

Grace (Jennifer Salt) witnesses the murder of Phillip from the neighboring building, in a dynamic use of split-screen.

With De Palma inviting Hitchcock into the discussion, let’s go ahead and talk about Psycho. Lisle Wilson’s Phillip Woode becomes an increasingly sympathetic character in the long stretch before his murder; by the time he decides to buy Danielle and her twin a birthday cake, and even jovially helps the incompetent baker write the words on the frosting, one wonders if Danielle could ever find a more perfect guy. Of course he’s doomed, but that it takes so long for Sisters to finally become a horror film owes a great debt to the structure of Psycho and its notorious use of Janet Leigh. I watched Sisters last Friday night in a 35mm print at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (part of their ongoing De Palma retrospective), so I wasn’t timing anything, but it certainly feels like half the film has elapsed before Woode meets his end. Yet it is in the murder of Woode that De Palma takes the reins from Hitchcock, utilizing a prolonged split screen inspired by its use in Woodstock (1970). The same year that Sisters arrived, another horror film had the same idea: Wicked, Wicked (1973). “MGM introduces a new film experience,” the poster proclaimed, “DUO-VISION. No glasses – all you need are your eyes. Twice the tension! Twice the terror!” But the split screen in Sisters is effective because it’s not a gimmick; it is naturally and logically integrated. It arrives at the precise moment in the film when we need more information – when we switch to the POV of small-time journalist Grace Collier (Salt), who sees Woode’s hand smearing blood on the window from her apartment across the street. Therefore the split screen is a hand-off in the thriller’s relay race; from here on out, we will be following Grace, not Woode. The split screen serves a metaphorical function as well, representing the separated Siamese twins of Danielle and Dominique. But even after Woode’s death, De Palma keeps the split screen running. We follow Grace as she calls the police and escorts them into the building, insisting they act urgently while, on the other half of the screen, Emil Breton (Finley), the “ex-husband,” arrives in the apartment to clean up the crime scene. There’s blood everywhere, so when he does get it all cleaned up before the policemen on one side of the screen can cross to the other half, it’s part of Sisters‘ inherent black comedy. (The film’s parodic overtones become more pronounced as the film goes on, so that this film actually leads organically into the overt spoof Phantom of the Paradise.) On this viewing I was fascinated by how De Palma doesn’t merely settle with split screen as a gimmick. He keeps playing with the images on both halves of the screen. Note how when the detectives arrive at Danielle’s door, he shifts that one camera back and forth to track Danielle’s nervous movements, or how, when she’s applying makeup in the mirror, there is another divide – in the glass, splitting her face symbolically in half.

Grace brings a private detective, Joseph Larch (Charles Durning), to the scene of the crime.

Charles Durning’s arrival, as private detective Joseph Larch, is not just the insertion of some comic relief, but represents a general shift in the film’s tone; increasingly, the film becomes both comic and surreal, even while it remains tense and creepy. In the trade-off, reality is left behind. Larch proudly announces his advanced investigative techniques, which involve posing as a window cleaner and infiltrating Danielle’s apartment, where he rifles through her things as Grace, watching from her own apartment window, essentially becomes James Stewart in Rear Window. Larch is in the apartment long enough to discover where the body has likely been hidden (the sofa-bed), as well as a secret file stolen from a mental institution. While Larch pursues the moving truck that’s carrying the furniture away, Grace reads the file and discovers that Danielle was one of the Blanchion Twins, Siamese Twins joined at the spine. But sister Dominique was said to have died during the separation. Now that we have our suspicions confirmed – that this will be a split-personality case along the lines of Norman Bates – De Palma springs a few more surprises upon us, in a delirious and suspenseful final act that sees Grace not just becoming the sinister Dr. Breton’s latest patient, but also a surrogate for the absent Dominique. In a black and white flashback/dream sequence that reflects late 60’s/early 70’s underground movie surrealism, Grace witnesses a grossly exaggerated version of the past unfolding while joined to Danielle’s side. Efficiently for this low-budget film, it allows De Palma to depict the twins without having to use any special effects to double Kidder. But more importantly, it sells the idea that Grace is becoming Dominique, having been fully integrated into the (literal and figurative) madhouse. De Palma would reuse this device in the key climactic flashback of another Hitchcock riff, Obsession (1976), and it would serve a similar symbolic end. But there is something more satisfyingly unhinged about Sisters‘ final act. Dr. Breton, having drugged Grace, leers over the camera, hypnotizing her, and I found myself squirming in my theater seat, wanting to look away. (Finley’s very good here.) The climax deliberately recreates bloody childbirth, entwined bloodstained fingers becoming entwined twin bodies – another doubling, pairing itself with the opening credits images of infants in utero. And the denouement, one of De Palma’s most tidy endings, hits its beats perfectly, as we witness both the lasting results of Dr. Breton’s mental dominance and Detective Larch’s hilariously absurd, never-ending quest for the truth.