In Hope, New Jersey, turn off at the cemetery and follow the old dirt road into the woods, and you’ll find yourself in Camp Crystal Lake. Don’t listen to crazy Ralph. “You’re going to Camp Blood, aintcha?” he’ll tell you. “You’ll never come back again. It’s got a death curse!” The sheriff will laugh it off with: “He’s a real prophet of doom, ain’t he?” But take care of yourselves. Back in 1957, a young boy named Jason Voorhees drowned out in Crystal Lake; the counselors who were supposed to be watching him were off having sex. A year later, two camp counselors were murdered right after sneaking off to have sex in a cabin. Maybe there was a connection? It’s June 13th, Jason’s birthday, and a Friday and a full moon to boot. What could go wrong? As long as everyone stays together, keeps the electric generator running, doesn’t allow themselves to get separated in the dark, and doesn’t sneak off to have sex, the night should go swimmingly. Ch-ch-ch, ah-ah-ah.

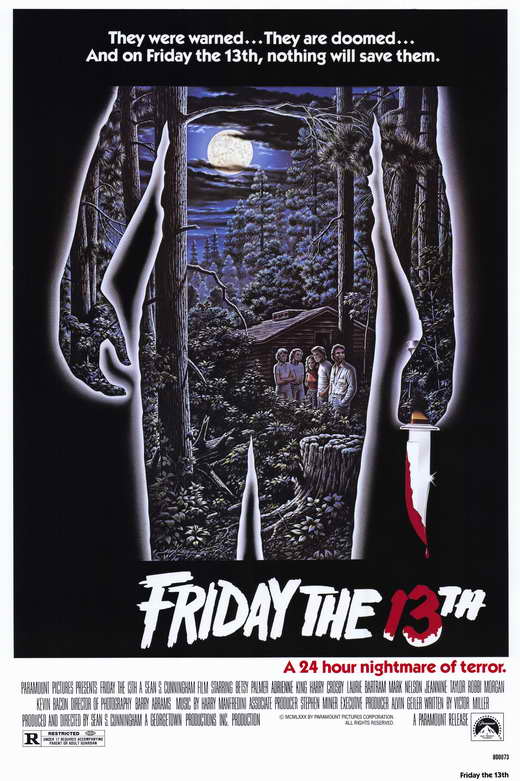

Marcie (Jeannine Taylor), Bill (Harry Crosby), and Alice (Adrienne King) in “Friday the 13th.”

Sean S. Cunningham, the producer of Last House on the Left (1972), decided to try his hand at the slasher movie by producing and directing the summer camp-set Friday the 13th (1980). The calendar-themed title evoked John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), the film’s primary inspiration, as well as Bob Clark’s cult classic Black Christmas (1974), but slasher films date back at least to Psycho and Peeping Tom (both 1960), and many of the genre’s techniques were refined in Italian giallos of the 60’s and 70’s, particularly those of Mario Bava and Dario Argento. Friday the 13th was the biggest hit of its kind since Halloween, and calcified the horror genre for the 80’s, to such an extent that when Fright Night (1985) came along, Roddy McDowall’s Peter Vincent famously lamented, “All they want to see are demented madmen running around in ski masks, hacking up young virgins.” What’s well known to fans but surprising for newcomers is that the series actually took a handful of films before it perfected its own formula. Jason Voorhees, killer of camp counselors, doesn’t appear in his trademark hockey mask until the third film, and he barely appears at all in the first. By then, the rest of the formula was already wearing pretty thin, because it was threadbare to start with. In Friday the 13th, there is virtually no story, and we don’t learn about Jason (apart from a quick reference to a drowning in 1957) until the final reel, when Mrs. Voorhees (Betsy Palmer, Mister Roberts, The Tin Star) offers the exposition that the rest of the film was lacking. Unlike the giallos, the Friday the 13th films are not known for their twisty plots. But it does follow the tradition of the summer camp movie, for which I have a weakness: a group of youngsters gather in the woods and hang out; the pace is relaxed, like a lazy summer day. Goof off by the lake. Take in some canoeing. Go hiking. At night, play Strip Monopoly (remember how we all used to do that when we went to summer camp?). “I’ll be the shoe,” says one girl with strange conviction.

Steve (Peter Brouwer) shows Alice what he’s got to offer.

The first film, in retrospect, benefits from its low budget, youthful cast, and general naiveté. Crazy Ralph (Walt Gorney, Nothing Lasts Forever) pops up shouting things like, “I’m a messenger of God. You’re doomed if you stay here!” – blissfully unaware that he will become an instant cliché, later sent up in films like The Cabin in the Woods (2012). Nonetheless, he returns in the second film in the series, and replacement Ralphs pop up later on. I enjoy the pointlessly extended scene of camp owner Steve Christy (Peter Brouwer) making a clumsy pass at Alice (Adrienne King) while wearing nothing but cut-off denim shorts, a red handkerchief, and his mustache. And King, with her bowl cut and slightly gawky charm, makes an ideal Final Girl for 1980. There are six camp counselors, with a seventh youngster, perky Annie (Robbi Morgan), in transit to serve as cook for the campground – she never arrives, her throat slashed in the woods. The other counselors include Jack (Kevin Bacon, well before Footloose), prankster Ned (Mark Nelson), sultry Marcie (Jeannine Taylor), Bill (Harry Crosby), and Brenda (Laurie Bartram). It’s an ideal number to be killed off one by one, the bodies hidden so that they can be revealed more or less at once in the finale, the heroine screaming as she encounters each one, as rules dictate. Makeup legend Tom Savini (Dawn of the Dead) is on hand for the gore effects, although they are nowhere near as spectacular as those in a superior-in-every-way campground slasher he’d work on subsequently, The Burning (1981). One girl does get an axe in the face, and Kevin Bacon is impaled through the throat. There’s also Mrs. Voorhees’ slow motion decapitation, a moment which becomes the catalyst for the film to follow. The killer, you see, is not Jason at all (not that you have much of a chance to suspect him, since he’s hardly mentioned), but his mother, wreaking vengeance for the neglect of her son back in 1957. The problem with this reveal is that witnessing murders from the killer’s POV, as happens through much of the movie, is a very different experience from seeing Betsy Palmer stumble around with a knife. She’s not very frightening, even when she is speaking in her son’s voice, as though possessed by the spirit of Jason.

Betsy Palmer as Mrs. Voorhees.

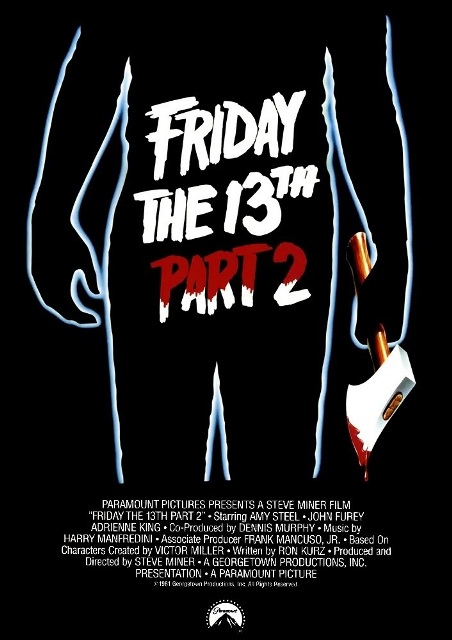

Perhaps the best known scene in the first film is its coda, which has echoes of Carrie (1976) and foreshadows the epilogue of future franchise rival A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). In an unexpectedly ravishing image, Alice lies in a canoe adrift in the center of Crystal Lake, the water creating a mirror image from below. On the shore, police cars pull up. Just as Alice awakens and touches the water, the decomposing corpse of young Jason vaults out from behind her. It’s all a dream, probably – she awakens in a hospital and warns that Jason is still out there (even though we’ve seen no evidence that he is, apart from the dream). Released just a year later, Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981) begins with an interminable flashback of the last film’s ending while Alice (a returning King) dreams restlessly. In film chronology, it is five years later. One night she opens her refrigerator and discovers Mrs. Voorhees’ severed head inside. Someone grabs her from behind and penetrates her skull with an ice pick. This pre-credits sequence borrows a bit from Psycho in its abrupt killing of its would-be protagonist, and it confirms her original warning: Jason is out there. Camp Crystal Lake lies abandoned. Instead, we travel to the nearby Counselor Training Center where Paul Holt (John Furey, Island Claws) instructs a small army of teenagers on how to be an effective counselor. When explaining how to avoid attracting bears, he offers the very specific advice to “keep clean during your menstrual cycles.” There’s so much fresh flesh that one expects a smorgasbord of killings for Jason Voorhees, but, in fact, there’s less than you’d expect. Some of the young actors don’t even get lines. The focus is instead on Paul, who resembles Fred from Scooby-Doo, and his equally blond girlfriend Ginny (Amy Steel, April Fool’s Day), who can quickly be identified as the new Final Girl. She makes a good one, too.

Amy Steel as Ginny.

Part 2, directed by Steve Miner (House), is a better film in some ways, mostly because of Steel’s strong performance, but also because the pacing is stronger and Jason (Warrington Gillette) finally gets to take center stage. Here, he wears a burlap sack over his head, with one eye-hole cut out. He’s a scary looking figure, but what’s interesting is seeing him behave in such a vulnerable fashion. He’s not the relentless undead zombie of later films, not a Michael Myers type, but a man with a child’s mind (albeit a slaughter-focused child) who fumbles when Ginny fights back. She even gets a chance to knee him in the balls. Depending on your tastes, this approach, quickly abandoned in series chronology, can be appealing: this Jason is a villain it’s possible to outwit and overcome. Her final confrontation with Jason involves impersonating his mother (which allows for a returning Betsy Palmer), and Jason cocks his head like a dog, confused. The story here is that Jason witnessed his mother’s decapitation, and he’s now begun his killing spree. Among the potential victims are dopey Jeff (Bill Randolph, Dressed to Kill) and his buxom girlfriend Sandra (Marta Kober, School Spirit); sex bomb Terry (Kirsten Baker, Midnight Madness) and Scott (Russell Todd, Chopping Mall), who lusts after her; wheelchair-bound Mark (Tom McBride, Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins) and Vickie (Lauren-Marie Taylor, Neighbors), who has a crush on him; Ted (Stuart Charno), requisite clown for this installment; and a little dog named Muffin.

Jason Voorhees (Warrington Gillette).

That’s not to mention all the other camp counselors who don’t get much screen time. Late in the film, almost everyone heads out to a bar and casino while others stay behind to face certain death. As mentioned, Crazy Ralph returns, just long enough to say, “I told the others. They didn’t believe me. You’re all doomed. You’re all doomed!” He’s killed off pretty quickly. Harry Manfredini, who contributed the memorable Jason theme to the first film, also returns for this installment. The kills aren’t that much more graphic than in the first movie – that is to say, they don’t reach the Fangoria-baiting proportions of later films – although one couple does get impaled together post-coitus. Out in the woods, Ginny encounters a shrine to Mrs. Voorhees with her severed head encircled by candles, an image which would, if nothing else, inspire part of the notorious Friday the 13th NES game. Special emphasis is placed on unmasking Jason, and we get a brief glimpse of his Toxic Avenger-like face. But the ending is curiously abrupt, perhaps because a final scene, in which Mrs. Voorhees’ preserved head smiles at the audience, was (wisely) deleted following test screenings. The film was another box office hit. Roger Ebert, who would quickly become an enemy of the franchise, wrote in his half-star review, “It is a tradition to be loud during these movies, I guess. After a batch of young counselors turns up for training at a summer camp, a girl goes out walking alone at night. Everybody in the audience imitated hoot-owls and hyenas. Another girl went to her room and started to undress. Five guys sitting together started a chant: ‘We want boobs!'” Director Miner may have been playing to the cheap seats, but he knew that for a Friday the 13th movie, all the seats were the cheap seats.