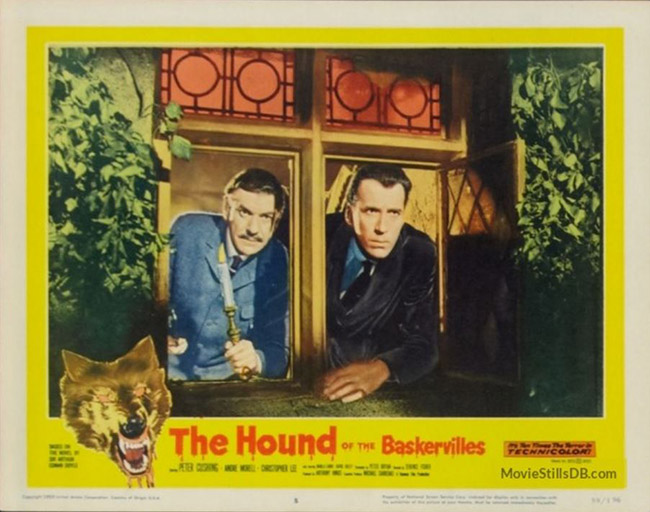

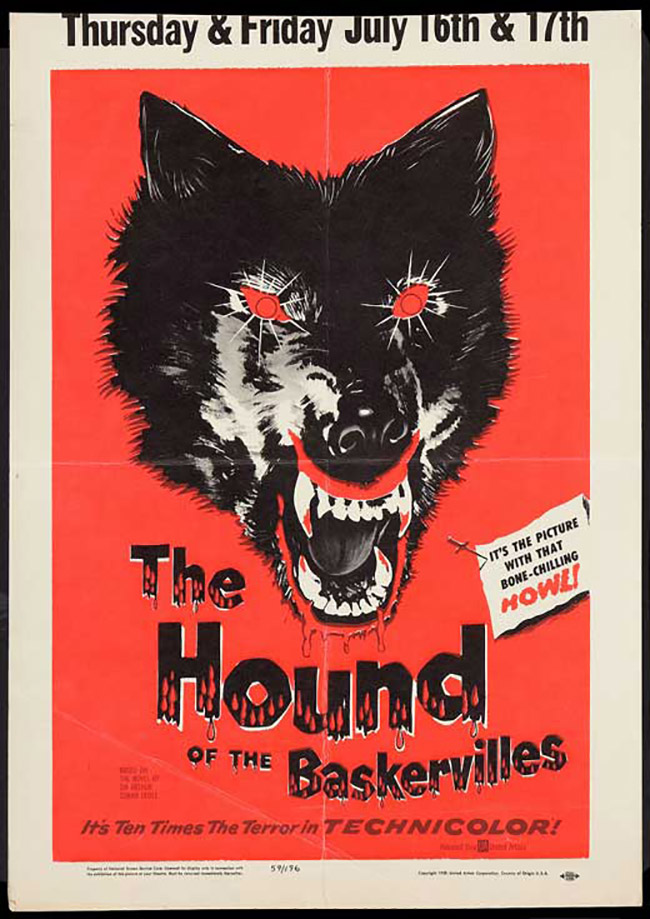

Reviewing The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) has me thinking about my favorite Hammer films, horror or otherwise. What follows is a list of the Hammer films I return to the most often and with the greatest pleasure. It’s not a list of the “essential” Hammer films, for the first thing you’ll notice is the lack of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Dracula (1958), and The Mummy (1959), which ought to be included on any list of that nature. Nor is it a list of the best overlooked Hammer films, for which I might include Quatermass II (1957), Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (1960), Cash on Demand (1961), or The Nanny (1965). No, these are simply the ones I’m most likely to upgrade when the latest physical media format is released, the discs I threaten to wear out. So no, Dracula isn’t on here, but the Count is present, as is Baron Frankenstein. These are simply my favorites…at the moment.

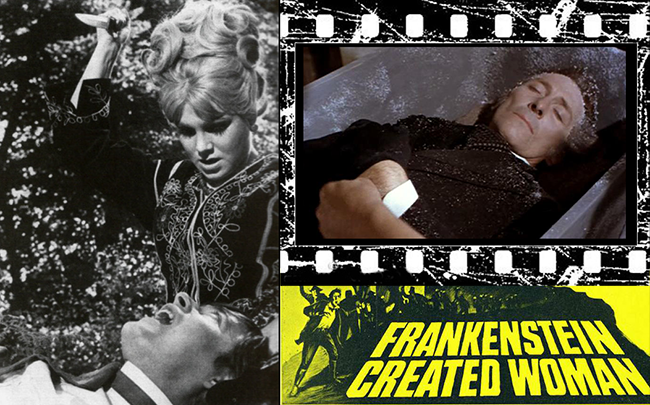

#10 Frankenstein Created Woman (1967) D: Terence Fisher

For the first few times I watched this film, I was astonished (yes, each time) that it was a completely different movie than what is suggested by its “Hammer Glamour” marketing. By now I’m very familiar with what Terence Fisher achieved, and can easily separate that from what’s suggested by the Roger Vadim-inspired title. Surprisingly lyrical despite a few gonzo elements, Frankenstein Created Woman, more than any other film in the long-running series, focuses upon those affected by the doctor’s experiments rather than the doctor himself. (Though it has been a fruitful vein for the franchise to mine, as seen in The Revenge of Frankenstein and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed.) Susan Denberg, far from being the sex object suggested by the film’s campaign, instead plays a disfigured peasant girl whose life takes a tragic turn; the Baron (Peter Cushing) gives her a second lease on life, which she uses to take revenge on those who wronged her. The final scene is heartbreaking – you don’t use that word often in the Hammer oeuvre. This is the film which Martin Scorsese has praised for its unique scene in which Cushing transplants a human soul, visualized as an orb of light.

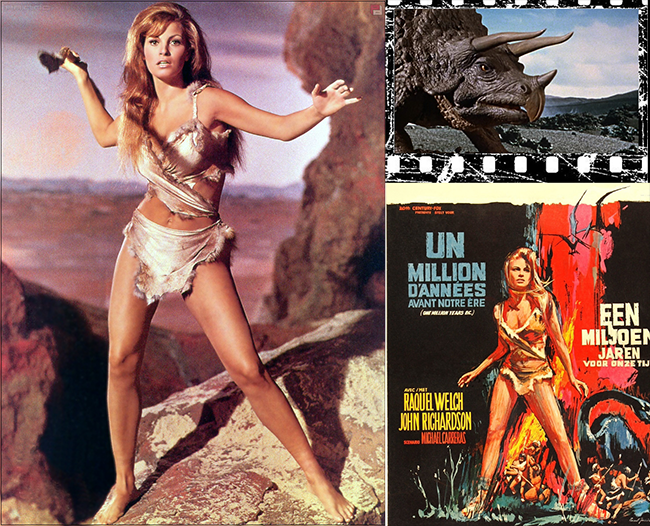

#9 One Million Years B.C. (1966) D: Don Chaffey

One Million Years B.C. enjoys the privilege of straddling two different but rabid fanbases: Hammer Films and Ray Harryhausen. It’s become an essential film in either category. For Harryhausen, the film was a chance to make a dinosaur picture without remaking King Kong, setting dinosaurs in their natural environment – prehistoric times – although obviously historical accuracy was out of the question, given the presence of cavemen. For Hammer, its success was the springboard for a number of prehistoric films leaning on the sex appeal of their lead actresses. An athletic and tan Raquel Welch wears a fur bikini, so who cares if none of the dialogue is in English? The stop-motion animation is some of Harryhausen’s very best, and – despite the camp appeal – there’s conviction to this big-budget survivalist spectacle which makes it perfect Saturday matinee fun. The film celebrates its 50th anniversary this year; I’ll post a full review of its forthcoming Blu-Ray release later this summer.

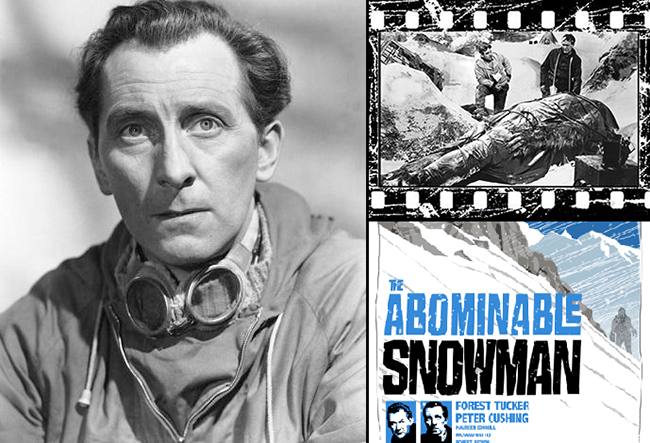

#8 The Abominable Snowman (1957) D: Val Guest

Hammer continued its rewarding association with writer Nigel Kneale with this adaptation of his 1955 teleplay The Creature. Peter Cushing and Forrest Tucker pursue the legend of the Yeti in the Himalayan mountains, but find themselves ill equipped to tackle the awesome force awaiting them. The Yeti is only briefly glimpsed, accomplishing the feat of both suggesting more than is shown and being completely satisfying. Val Guest was adept at tackling Kneale’s tough-as-nails and scientific approach to SF, as he demonstrated with the first two Quatermass films; with The Abominable Snowman, he perfectly expands this style into horror and fantasy. The score by Humphrey Seale is superb, evoking the snowy Tibetan wilderness, and the film is further enhanced by some location shooting with real mountain climbers.

#7 Scream of Fear (1961) D: Seth Holt

Seth Holt didn’t direct many films for Hammer, but when he did, they were worth watching: in addition to Scream of Fear, he was responsible for The Nanny (1965) and Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971; though he died during filming, and the production was completed by Michael Carreras). Susan Strasberg plays a wheelchair-bound young woman who goes to stay with her father after the death of her mother; but Father is mysteriously away, and she begins to suspect that he’s been murdered, possibly by her stepmother. The conspiracy turns out to be something quite different than expected. I’ll never forget how I first saw Scream of Fear, at a movie theater which specialized in revivals, and on a double bill with The Revenge of Frankenstein. The audience was completely absorbed by the story, and delighted at the final twist(s). The lush black-and-white photography also looks stunning on the big screen. This is the best of Hammer’s straight-up suspense films, with a screenplay by Jimmy Sangster. Christopher Lee, who has a small role, called this the best Hammer film he ever appeared in.

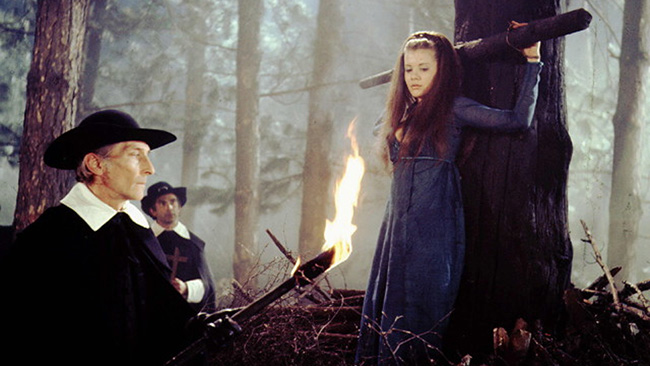

#6 Twins of Evil (1971) D: John Hough

In my house, right beside the original Scream of Fear poster, you’ll find one for Twins of Evil. “One uses her beauty for love! One uses her lure for blood! Which is the virgin? Which is the vampire?” That’s about as good as ballyhoo marketing gets. Twins of Evil delivers on the exploitation potential of its poster while offering one of the best performances Peter Cushing ever gave. Much as how Witchfinder General (1968) brought out a different side of Vincent Price, Twins of Evil demonstrated a darker, more ruthless, and unquestionably haunted Cushing, no doubt informed by the devastating loss of his wife just prior to shooting. (Cushing was never the same.) Yet this is also the film in which twin Playboy Playmates Mary and Madeleine Collinson wear semi-transparent negligees while one of them falls to the allure of vampirism. It’s the third and best in the informal, Carmilla-inspired “Karnstein Trilogy” (following The Vampire Lovers and Lust for a Vampire), and a prime example of how Hammer tried to adjust to the 70’s and its loosening censorship.

#5 The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) D: Terence Fisher

It’s surprising that Hammer didn’t embrace the werewolf quite as much as they did vampires, Frankenstein’s monsters, and mummies. The Curse of the Werewolf doesn’t feature Lee or Cushing – and it had no sequels – but it did provide one of the iconic movie Wolf Men, and introduced Oliver Reed to wider audiences. Reed is well suited for a role in which it’s impossible to imagine the studio’s two marquee stars. Reed is young, handsome, tormented, and seems capable of brute violence – qualities he displayed to strong effect in Hammer’s excellent Cold War thriller These Are the Damned (1963). Although the story is familiar (a loose adaptation of Guy Endore’s The Werewolf of Paris, transposed to Spain), it feels fresh and vital thanks to the literate screenplay by Anthony Hinds and the sensitive direction of Terence Fisher. It’s just damn fine storytelling, with an added emotional potency that Reed completely sells.

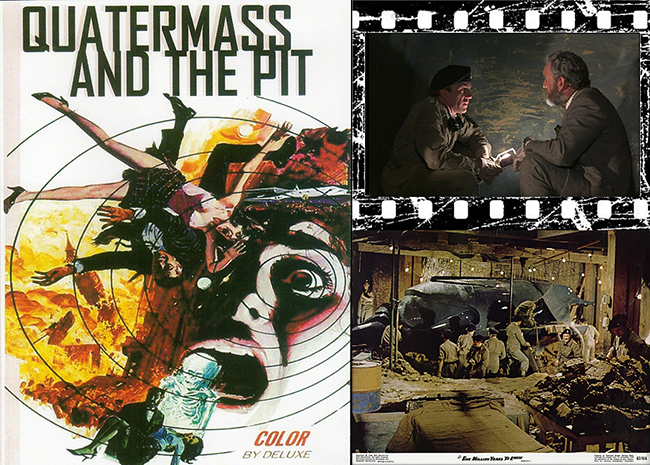

#4 Quatermass and the Pit (1967) D: Roy Ward Baker

One of John Carpenter’s favorite films, Quatermass and the Pit was the last of Hammer’s Quatermass trilogy after a gap of ten years from the prior installment. It’s also the best of the series – which is saying a lot, given that the first two films are wonderful. Nigel Kneale famously complained about the Quatermass of the Val Guest films, the brash American actor Brian Donlevy, who was present simply to sell American tickets. The Scottish Andrew Keir perhaps embodies a more appropriate Quatermass, but the star is once again Kneale’s story, a compelling science fiction mystery (with teases of the occult) which explodes into an apocalyptic epic in its final reel. This first-class thriller justifies Hammer’s return to the character who helped jump-start the studio; I’ve yet to encounter anyone who’s seen it who doesn’t love it.

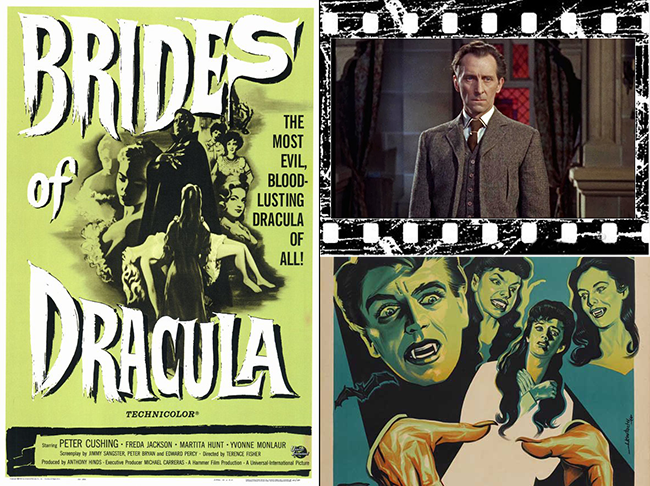

#3 The Brides of Dracula (1960) D: Terence Fisher

Here’s what the Dracula series might have been: like the Frankenstein films, one consistent human protagonist with a rotating cast of monsters. Lee thought he might avoid typecasting by not appearing in the sequel (little did he know), so instead Cushing returned as Professor Van Helsing, and a welcome return it is. Here he’s pitted against Baron Meinster (David Peel) and his harem of vampire women, with the white neck of the beautiful Yvonne Monlaur at stake. Once more Terence Fisher proves he was the ideal director for this sort of thing, memorably staging tense scenes such as Van Helsing actually succumbing to a vampire’s bite (and his hurried and self-administered treatment) and his final vanquishing of his foe, which might be absurd in concept, but is so spectacularly realized that it’s bound to earn your applause. The next Dracula film would be long in coming, but it would finally see the return of the Count; Dracula – Prince of Darkness (1966) has some fantastic scenes but doesn’t have quite the imagination and energy of this immediate sequel.

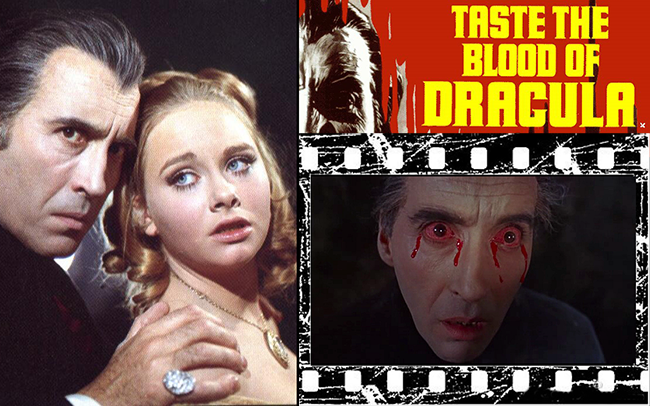

#2 Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970) D: Peter Sasdy

This sequel shouldn’t be as strong as it is. Lee had once again sworn off playing the Count, but his appearance was negotiated at the last moment, and the sloppy rewrite is evident in the script. This might have been a film in which Ralph Bates took the role of Dracula’s disciple; instead, he is literally replaced by Lee, who resurrects himself through Bates’ body (almost halfway through the film). With Lee’s absence planned, the script places emphasis not on the standard Dracula-stalks-his-victims plot of the last couple of films, but instead on a theme of youth revolting against the hypocritical older generation. Basically, this is a movie for the hippie era, except with Victorian costume instead of bell-bottoms. After moral icon of society Geoffrey Keen chastises teenage daughter Linda Hayden for wanting a boyfriend and locks her in her room, he visits a whorehouse with his two compatriots and seeks more perverse thrills with the aid of occultist Bates. When Hayden and Isla Blair finally fall under the command of Dracula, they murder their parents by driving stakes through their hearts, inverting the vampire formula. It’s endlessly disappointing that Dracula’s demise is an afterthought, but forget the silly final minutes: this is one of the most compelling and thoughtful films in the series.

#1 The Devil Rides Out (1968) D: Terence Fisher

Not just my favorite Hammer film, The Devil Rides Out is also, I believe, the very best the studio ever produced. As censorship became more relaxed, Hammer could finally tackle the occult-themed books of Dennis Wheatley, with Lee playing Duc de Richleau, Wheatley’s fearless fighter against the forces of Satanism. Fisher, completely invested in the material, employs an impressive ensemble including Charles Gray as the mesmerizing, devil-worshiping Mocata, perhaps the most evil and frightening character in Hammer’s filmography; the elegantly beautiful Nike Arrighi as Tanith, an occultist who finds herself in too deep with Mocata; and Leon Greene, Patrick Mower, Paul Eddington, and Sarah Lawson as the forces of good, struggling to follow Lee’s strict instructions, especially to stay inside that damn magic circle. One thrilling sequence follows another; the pace never lags. Promises of a remake have come and gone over the years, but its influence can be felt in films like Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate (1999) and Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell (2009).