This post is a proud part of the Dorothy Lamour Blogathon (March 11-13) hosted by Font & Frock and Silver Screenings. Be sure to check out all the excellent essays on the films of Dorothy Lamour!

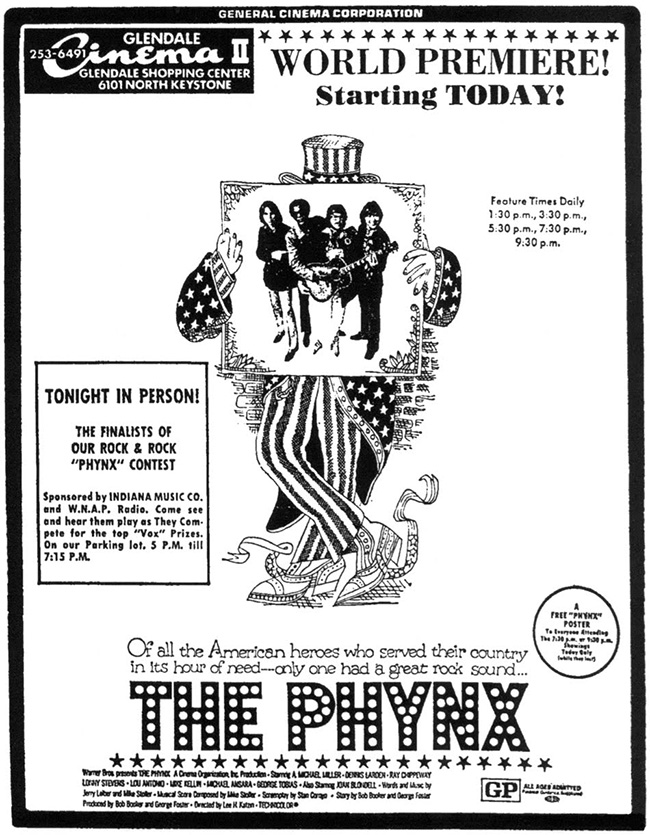

Dorothy Lamour has been kidnapped by Albania! So has Joe Louis, Johnny Weissmuller & Maureen O’Sullivan, Andy Devine, Leo Gorcey & Huntz Hall, Busby Berkeley, Edgar Bergen & Charlie McCarthy, George Jessell, and other American treasures! Who can infiltrate Communist Albania and save them? The answer is obvious: a manufactured pop band called The Phynx (1970). This Warner Bros./Seven Arts film was directed by Lee H. Katzin, a television director with just a smattering of theatrical films to his name, including What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? (1969) and the Steve McQueen-starring Le Mans (1971). The producers, Bob Booker and George Foster, would go on to “The Paul Lynde Halloween Special” (1976), and the screenwriter, Stan Cornyn, was an exec and record producer at Warner Bros. Records – this was his only screenplay. A bit more promising for this ostensible rock musical were the two names credited with writing the original songs: Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, the legendary pop craftsmen who wrote “Hound Dog,” “Jailhouse Rock,” “Kansas City,” “Searchin’,” “Yakety Yak,” and “Is That All There Is?” But by 1970 their hits had dwindled, and perhaps they weren’t the hippest choice for a counterculture rock and roll movie. That’s the thing: The Phynx isn’t a hip film. Rather appropriately for a film about a pop band cynically created by the U.S. government for their own purposes, The Phynx comes across like a Narc – stealing into the party wearing clothes two years out of fashion, throwing out tortured teen lingo, oblivious to the eyerolls. The film was barely released in the spring of 1970, and remained obscure until Warner Archive released it on DVD. It’s a time capsule for a year when Hollywood didn’t know what to do with itself. The film is hilariously square, but also deeply strange. The same year 20th Century Fox would release Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), to which The Phynx seems like a PG-rated cousin.

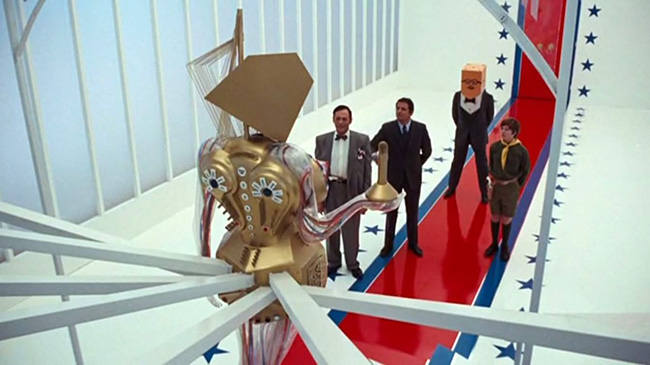

Bogey (Mike Kellin), Corrigan (Lou Antonio), and the box-headed Number 1 (Rich Little) consult M.O.T.H.A. with the assistance of a boy scout.

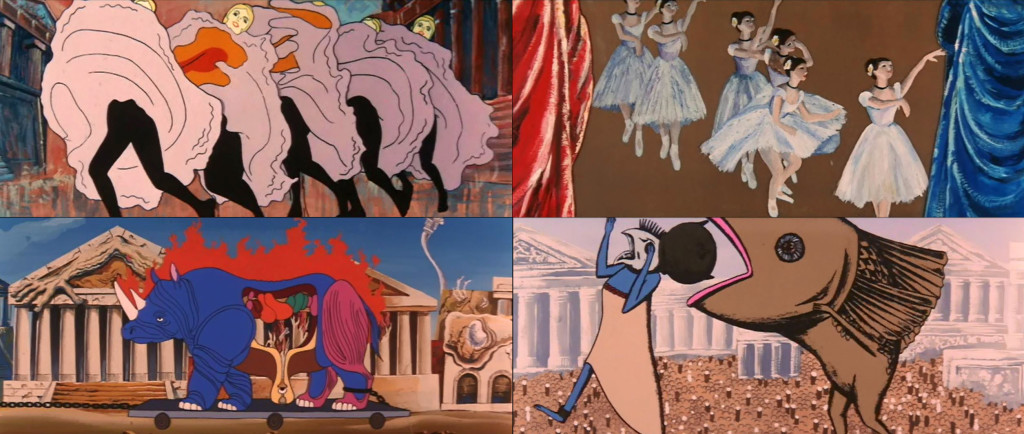

The film begins with a number of broad, cartoonish gags in the manner of later Pink Panther films, as Corrigan (Lou Antonio, Cool Hand Luke), a spy for the Super Secret Agency, attempts to pass through a wall that separates Albania from Yugoslavia, thwarted in each ridiculous attempt by Colonel Rostinov (Michael Ansara, The Doll Squad); his last attempt is to pose as a human cannonball in a circus, while Rostinov’s men catch him in a giant canvas target on the other side of the wall. This is followed by an animated opening credits sequence, which, in the grand tradition of animated titles, features nothing remotely funny. The Phynx briefly becomes Get Smart as Corrigan returns to the Super Secret Agency via a hidden door in a bathroom stall, whereupon we meet Bogey (Mike Kellin, The Boston Strangler), the head of the Super Secret Agency, who is either a Humphrey Bogart impersonator or Bogart himself. His Super Secret Agents gather in a hall, wearing their disguises: Black Panthers, Hell’s Angels, Ku Klux Klan, Boy Scouts, prostitutes, “Invisible Men” (empty seats), and so on. Number One, a man with a box for a head and the voice of Rich Little, explains that more and more celebrities have been kidnapped by Albania, and a new plan of attack is needed. On the advice of one of the Boy Scouts, Number One, Bogey, and Corrigan consult M.O.T.H.A. – “Mechanical Oracle That Helps Americans” – a female-shaped computer. M.O.T.H.A. produces the plan to form a pop group so popular that Albania will want to capture them. It even invents the meaningless name: Phynx. It’s the kind of satirical jab that you might expect to see in the Monkees’ Head (1968) – as the band sang in that film, “You say we’re manufactured/To that we all agree/So make your choice and we’ll rejoice/In never being free.” But The Phynx never digs that deep. It wants to create the new Monkees (if not The New Monkees). The fact that the members of The Phynx are drafted is explored only so far – and largely forgotten by the end of the film. The Phynx does rejoice that they’ll never be free, and the irony is nowhere to be found.

The Phynx records “What Is Your Sign?” for the Phil Spector-like producer Philbaby (Larry Hankin).

To further the Monkees comparisons, each member of the band has the same name as the actor playing him. Dennis Larkin is a Nebraska college student; Michael A. Miller is the hunk and ladies’ man; Ray Chippeway is Native American; Lonnie Stevens is African American. Stevens is treated better than Chippeway, who is subjected to a string of truly bad, racist jokes. The U.S. captures him by luring him into the “Firewater Saloon,” and Chippeway is given to deliver lines like “How, Whitey.” But the politically incorrect coup de grâce might be his father insulting his son’s hip clothes with the line, “White man turn son pansy.” (These kinds of jokes rather undermine the film’s attempt to show Chippeway as embittered at the American government’s treatment of his people.) Meanwhile, Stevens, apparently the only member of the band to go on to a career in Hollywood, gets perhaps the most honest moment of the movie when he commiserates with Richard Pryor, appearing in a brief cameo, telling the comedian that he’s better than doing stuff like this. (He’d be proven right.) Pryor is part of the “Super Secret Summer Camp 17,” a boot camp where Corrigan escorts the band through various mentors: Pryor teaches them soul; Trini López teaches them guitar; Dick Clark evaluates their fashion. At last a Phil Spector type, named Philbaby (Larry Hankin, Planes, Trains & Automobiles), is literally airlifted into the studio and gives the band a hit song, “What Is Your Sign?” The lyrics include:

What is your sign?

Don’t make me wonder

What is your sign?

What sign were you born under?

This immediately becomes a massive hit, and James Brown delivers a gold record for “the largest selling album in the history of the world” to their agent, Bogey. Granted, much of the success is delivered by force. Ed Sullivan (as himself) introduces The Phynx at gunpoint. Bogey storms into a record store and shoots up the competition’s records with a Tommy gun, spelling P-H-Y-N-X with bullet holes. But kids go crazy for The Phynx. Richard Nixon (in stock footage) signs a bill changing Thanksgiving to Phynxgiving. One of the band members appears on the three dollar bill.

Some of The Phynx’s many cameos: Dorothy Lamour, James Brown, Joan Blondell and Colonel Sanders, Charlie McCarthy and Edgar Bergen, Richard Pryor, Harold “Oddjob” Sakata.

In all fairness, some of the songs are pretty good, and – much like the Monkees’ – they vary in style, as though different songwriters had contributed them. If you played me “Hello” (perhaps the best song in the film) and claimed it was written by Harry Nilsson, I’d have believed it. Other songs range from soul to AM radio to the outright bizarre (“They Say That You’re Mad,” a song which I think Leiber and Stoller thought was hard rock…). Without a doubt, the songwriting is just as manufactured as The Phynx themselves, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t points of interest. The same goes for the songs by the Carrie Nations in the superior Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, but what that film has going for it – as well as the Monkees’ Head – is a genuine sense of subversion. There’s no Russ Meyer & Roger Ebert or Bob Rafelson & Jack Nicholson involved in The Phynx, and subsequently there’s no bite, not even when the band members complain about the Draft or Larkin returns to his college to face rejection from his peers for dressing like a hippie. (This was 1970. This might have had an edge years earlier.) Even the PG-rated sex doesn’t come off as satirical so much as sexist. The Phynx has a government-sanctioned orgy, and in the Morning After scene, passed-out women are removed with a forklift. The band receives a mission to discover secret maps tattooed on the bellies of three different women, and their techniques to discover the maps include X-ray glasses and having sex with hundreds of blonde girls lining up to “Meet the Phynx.” As for the political humor, it doesn’t go much deeper than Colonel Rostinov boasting of Albania’s “finest hotel, Communist Hilton.”

The Phynx performs before an oddly appreciative assortment of Hollywood stars.

The real reason The Phynx seems to exist is to act as a Golden Age of Hollywood class reunion, a farewell to retired actors, comedians, and other showmen. It’s as though the producers went door to door in Hollywood handing out flyers. In an Albanian castle, the stars are introduced one at a time, smiling and nodding to the camera, then taking their seats: Tarzan and Jane (Weissmuller and O’Sullivan), Bowery Boys (Gorcey and Hall), Guy Lombardo, Butterfly McQueen, George Jessell, Jay “Tonto” Silverheels, Clint Walker, Andy Devine, Busby Berkeley and the Gold Diggers, boxer Joe Louis, and more. Keep in mind that they’re all gathered to watch a rock concert by The Phynx. Dorothy Lamour is beaming. Butterfly McQueen seems to genuinely be enjoying herself. Many are good sports about not trying to look confused (though they should be). But, as one member of the band puts it, “Either we get these people out or we get drafted!” (They already have been, but never mind.) The celebrities are smuggled out of the castle where they’ve been imprisoned – forced to eat buckets of KFC from Colonel Sanders himself – and the Phynx gives one final concert for the Albanians. The climactic song, “(How About a Little Hand For) The Boys in the Band,” rocks so hard that a tank splits in half and the Albanian wall topples. All of the film’s elements mix as well as oil and water, but The Phynx is never, not for a moment, unwatchable. Still, the fact that nobody watched it is the only thing about the movie that makes a lick of sense.