This post is a proud part of the Movie Scientist Blogathon hosted by Christina Wehner and Silver Screenings. Visit those websites to check out all the participants’ entries.

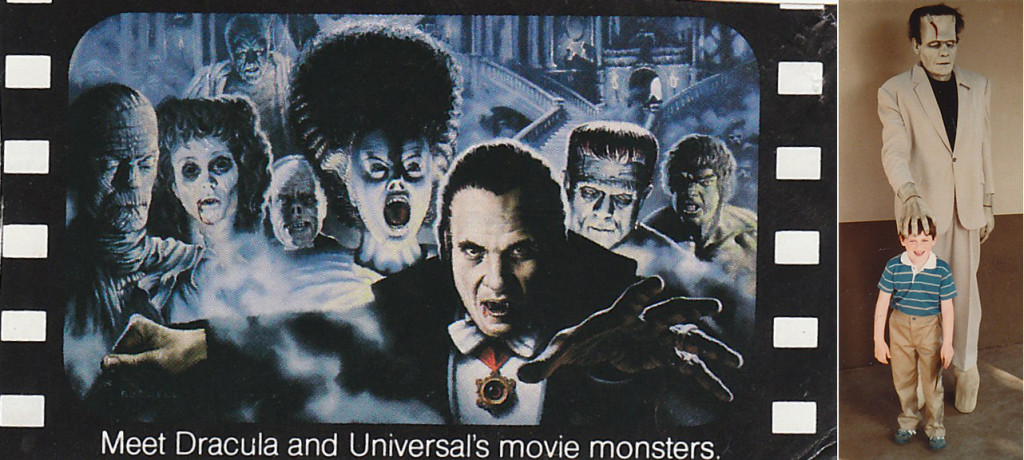

In the early 80’s, my parents took me to Universal Studios. While we were waiting in line to get inside, Frankenstein’s monster was over in the corner, up against a wall, just kind of hanging out. Not moving. But I suspected one of two things: that it wasn’t a mannequin but a real person under makeup; or, most worrying, that it really was Frankenstein’s monster. My parents asked me to go stand in front of him so they could take a picture. I approached him with great caution. Turned, smiled. For a fleeting instant, as I recall, I was convinced that it was all right, that it was just a mannequin, just some Frankenstein’s creature that was shot and stuffed. That’s when I felt the hand clamp down upon my head. The picture was snapped. I ran. (I recently came across the photo in an old album, and rescued it from corrosive adhesive. Scroll down to see it.)

Although I had an early interest in horror, I wasn’t allowed to watch R-rated films, not until I was older, so when it came to monster movies – always my preference on the horror spectrum – I was either stuck with reading about them in library books (including binder-bound compendiums of Famous Monsters of Filmland) or watching the ones that were deemed safe, namely old, classic films. I learned the names Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, and Lon Chaney Sr. and Jr. from a very young age. I became obsessed with Frankenstein, Dracula, and other Universal Monsters. Even in college, in a Creative Writing class I submitted a poem about Colin Clive, who plays Dr. Henry Frankenstein in the 1931 film. (No, I won’t be sharing that. Some things are better left…buried.) Although I’ve generally preferred the more dynamic character of Dracula, clearly Frankenstein’s creation has always followed just behind me, his hand hovering above my head.

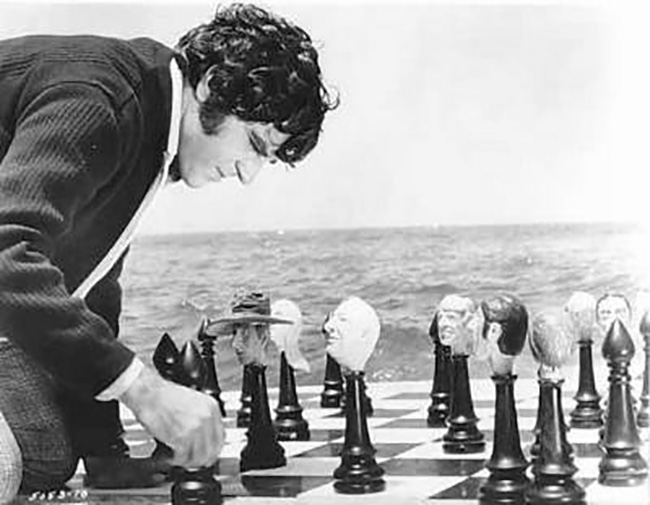

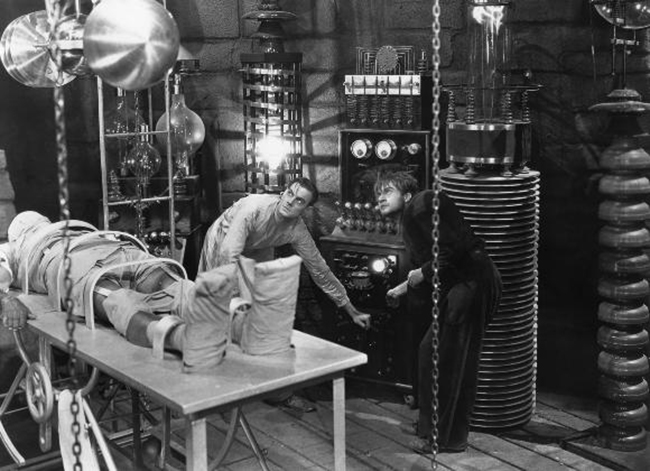

Publicity still of Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) and his assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye) at work on the monster.

Frankenstein (1931) is a remarkable horror film, although it has become so appropriated into pop culture that it’s almost impossible to watch it with fresh eyes. After James Whale’s film, Mary Shelley’s original 1818 novel – and its monster in particular – was practically displaced. Shelley’s creature, which is brought to life by obscure means, is intelligent and eloquent, and enacts a cruel revenge against his creator for abandoning him at the moment of his birth. Over the decades many have tried to present the novel without neck-bolts, either on stage (such as in Danny Boyle’s 2011 Frankenstein starring TV’s two Sherlocks, Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller) or on the big screen (including Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 film Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein); on the small screen, TV’s Penny Dreadful presents a surprisingly faithful version of the monster, even if the story goes in wilder directions. So – the book is fantastic, but it is not the Whale film, and that’s perfectly all right, because the story it does tell is a valid and intriguing variation. The monster never gains adult sophistication; he remains a monstrous child. There’s no epic journey across land and to the Arctic – nor is there room for it in this 70-minute film, based on a stage play by Peggy Webling. What it does share with Shelley’s book is an interest in the creator/creation relationship; the father who abandons his son like the progeny of a one-night stand, only to find that he can’t escape the past; the madness of obsession, as Frankenstein neglects family for his work; and a rumination on what it means to create life. Whale’s film has a lot going on – it’s an intellectual film, and to make the ideas work as concrete things, his landscape visualizes the tormented psychology of Frankenstein and his monster.

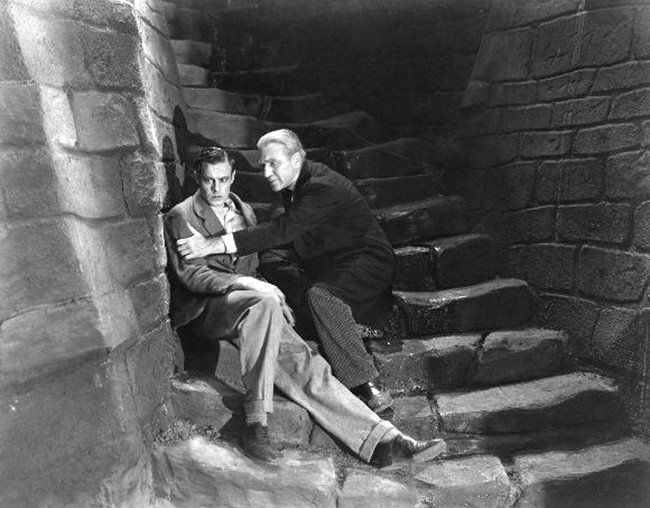

Henry Frankenstein and Dr. Waldman (Edward Van Sloan).

That is, of course, the forté of German Expressionism. Originally slated to direct Frankenstein was Robert Florey (The Cocoanuts, Murders in the Rue Morgue), who began planning a film that would rely heavily on Expressionism for its artistic design: slanted sets and stairways of the abandoned watchtower where he works, a graveyard on a hill, its Gothic tombstones leaning over and casting long shadows. Florey was replaced by James Whale (Waterloo Bridge), but Whale kept the design choice. Frankenstein looks like a cousin to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) or the silent films of F.W. Murnau. Only in the drawing rooms of the upper crust does the film regain straight angles and sensibility. The contrast is appropriate for the fractured personality of Henry Frankenstein. At the start of the film, he has become so focused upon his goal of creating life from dead bodies that he has isolated himself from his fiancée Elizabeth (Mae Clarke, of Whale’s Waterloo Bridge), and frequents cemeteries and gallows with his hunchbacked assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye, in another iconic role following his Renfield in Dracula). Fritz, with his twisted body, seems to represent what Henry’s soul has become. Refreshingly, there are no scenes of Henry debating whether or not to go grave-robbing; he is introduced embarking on the mission without regrets. A short while later he instructs Fritz to cut down a hanged body, only to lament, “The neck’s broken, the brain’s useless. We must find another brain!” This Fritz does, although he smashes the “Normal Brain” jar and substitutes the “Criminal Brain” nearby. (It is impossible to watch this scene now without thinking of Marty Feldman and Young Frankenstein.) By the time Elizabeth, Victor (John Boles, Stella Dallas), and Dr. Waldman (Edward Van Sloan, Dracula‘s Van Helsing) arrive at Henry’s lab, he insists they sit down and watch as he creates life from scratch. “Quite a scene, isn’t it?” he says, aware of their gaze in that you-think-me-mad sort of way, derisive, couldn’t care less. Colin Clive gives the essential mad scientist performance – his initial annoyance at being interrupted succumbs to a delirious, blind pride in what he’s about to accomplish. His cry of “It’s alive!” is orgasmic – crucially followed by the (oft-censored) line, “Now I know what it’s like to be God!”

The monster (Boris Karloff) discovers sunlight.

As perfect as Clive is in the part, naturally it’s Boris Karloff who steals the show. The British-born Karloff had acted as an extra in countless films before, but this was his first prominent role – as the story goes, Whale spotted him in the Universal commissary eating lunch, and was struck by his gaunt features. He knew he had his monster. Karloff was 43, but his whole career was ahead of him. In the opening credits, his credit is replaced by a question mark to add to the mystery – what will this monster be? Maybe not even an actor, but a special effect? Or perhaps a real monster – like what I suspected when I approached the creature at Universal Studios as a kid. In the ending credits Karloff’s name finally appears, and in re-issues his name was featured prominently on the poster, for by then he had become a horror icon. Under the genius of makeup artist Jack Pierce, Karloff endured 3-3 1/2 hours of makeup each morning, and it took almost as long to remove it. It was Karloff’s idea to build up heavy, drooping eyelids, giving his creature a corpse-like appearance which retains a genuinely eerie effect. Pierce’s brilliant makeup design, with the flat skull and neck bolts (for charging him like a battery), quickly became synonymous with the word “Frankenstein.” It’s hard to imagine there was a time when this version of Frankenstein didn’t exist. Imagine achieving something like that in your life; it’s like inventing coffee. Famously, Lugosi turned down the role, back when it was going to be a Robert Florey film, although at the insistence of Dracula and Frankenstein producer Carl Laemmle Jr. he did undergo a makeup test on June 16th and 17th of 1931. With both Florey and Lugosi out, they were handed Murders in the Rue Morgue instead. Lugosi’s most triumphant follow-up to Dracula was the dream-like White Zombie (1932), but the quality of his roles, and the quality of the productions, declined while Karloff found better fortune with a wider variety of interesting turns in films like The Old Dark House (1932, for James Whale), The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), The Black Room (1935), a trilogy of thrillers for Val Lewton (The Body Snatcher, Isle of the Dead, and Bedlam), and many, many others.

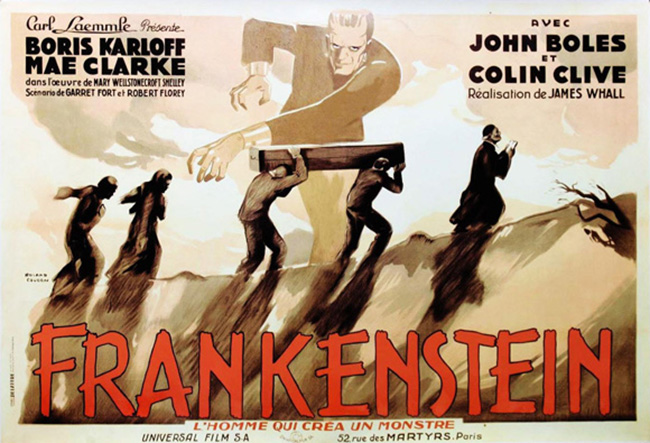

Lobby card for the film’s re-issue.

But in Frankenstein Karloff found his ideal role. Because his makeup relied so much upon his own features, the camera could capture the actor’s emotions, the monster’s fleeting joys and depths of anguish. From the very start the creature is a physical threat, capable of great violence, but it’s the torture-by-torch that he endures from the sadistic Fritz that actually foments any monstrous qualities he possesses. Henry allows the creature to be locked away. He allows Fritz to do what he will. He’s a neglectful father. When the creature sees sunlight from a high window in the watchtower and reaches skyward in wonder, it’s heartbreaking. But the true wrenching moment is one of the film’s most famous scenes, as the monster, wandering free, meets a little girl throwing daisies into a river. Unafraid of the creature, she demonstrates her little game – making the daisies float. He plays along with her, until he runs out of daisies and decides to throw her into the water instead. It’s an innocent violence (and a moment that Karloff reportedly tried to dissuade Whale from filming); the creature is still a child, unaware of his own power. This act culminates in the powerful moment when the girl’s father carries her limp body through a crowd of villagers during a festival. Whale’s camera tracks with the father as he walks, his face frozen in grief. In the background, the villagers are still smiling as they drift through the shot, but their smiles fade as they see what’s moving through the foreground. I love Tod Browning’s Dracula, but moments like this prove why Whale pulled off the better film. Unlike a lot of early Talkies, Frankenstein doesn’t forget the lessons of the Silent Era. You could watch the film without sound and understand it perfectly.

The original Mad Scientist.

While the monster enacts his tragedy – born, abused, misunderstood, hunted – Clive’s Henry Frankenstein emerges from his delirium and into the sunlight with the promise of a happy marriage with Elizabeth. He’s a new man, like an addict who’s successfully gone cold turkey. “My work – those horrible days and nights – I couldn’t think of anything else,” he says. He’s healed by Elizabeth, but he’s also walked away from his creation. Similar to Shelley’s novel, his sin is not just creating life with the hubris of a man who wants to imitate God, but in not properly nurturing the life he’s created. There’s a toast in the film – “Here’s to the son to the house of Frankenstein!” – which indicates that his path will now take him to nature’s preferred method of creating life. But Henry can’t cut the ties to his creation, and the monster goes after Elizabeth. Ultimately Henry will find himself tracking down the creature as it flees the prototypical lynch mob of angry villagers. A windmill burns, and the monster screams, surrounded by fire. There’s almost something ritualistic about the film. It’s myth-making, separate from the novel. There would be interesting sequels, including Whale’s phenomenal Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Rowland V. Lee’s Son of Frankenstein (1939). There would be the monster mashes of the 40’s, and the resurgence of Frankenstein and his creation(s) by Hammer in the 50’s through the 70’s, with Peter Cushing as a more coldly calculating doctor, unafraid to get his hands bloody. But there’s an undiminished spark in the 1931 film which remains untouchable. It’s the spark of creating a new life from an 1818 novel – of stitching together something unique, which will march on no matter how many windmills come crashing down.