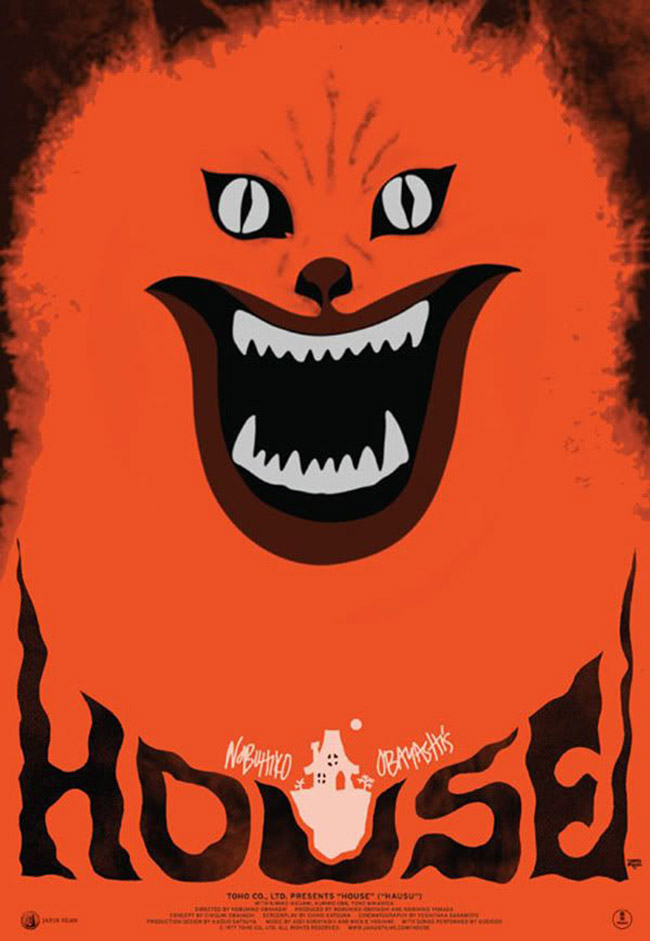

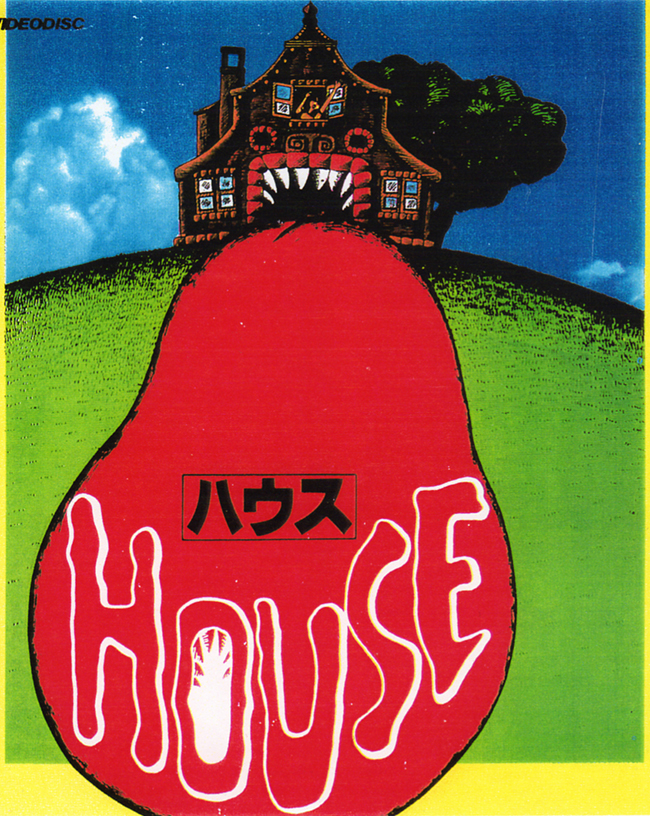

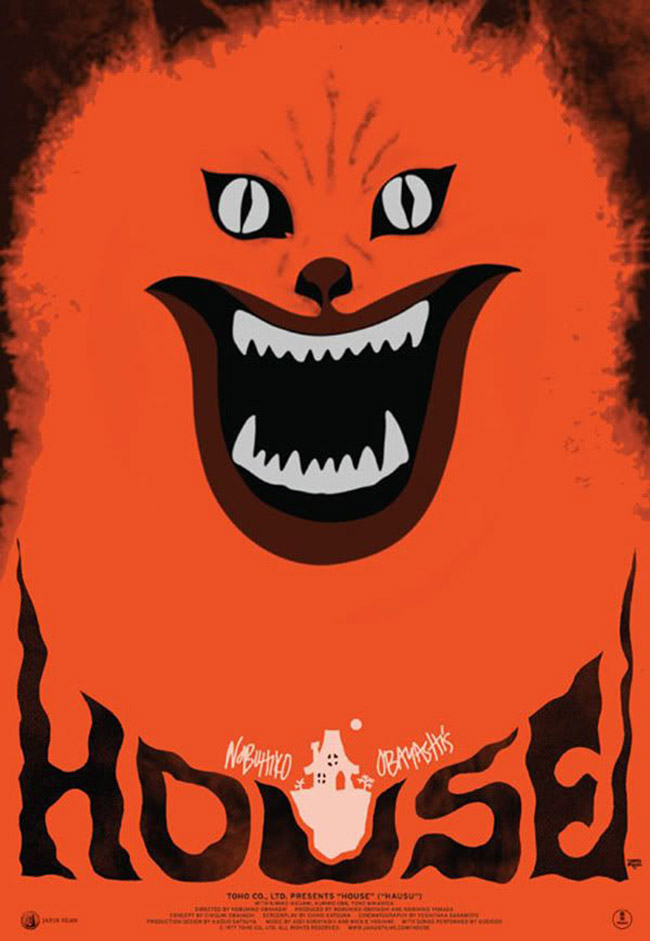

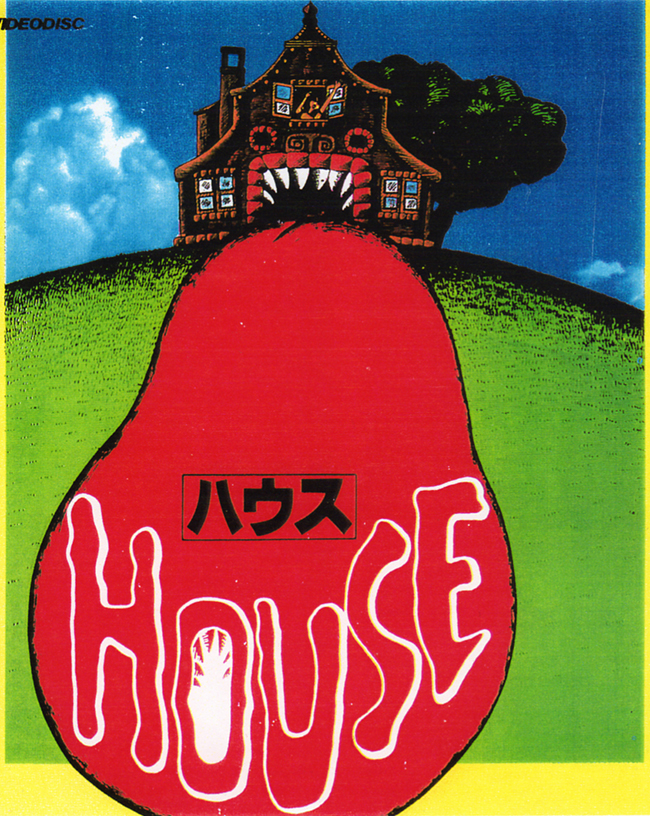

Exactly five years ago today I started up Midnight Only, and to set the appropriate tone, for the site’s first film I settled upon Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (1977). I figured House was a good place to start because I saw it as the most distant point in the cinematic cosmos, a pre-CG film in which nearly every shot contains a lovingly handmade special effect or some other piece of invention, a Toho horror movie with Attention Deficit Disorder that can’t let a moment go by without some absurd soundtrack effect or a whiplash transition, a completely, defiantly unconventional movie-movie. On the surface this story about a house that eats Japanese schoolgirls is simply a parody of haunted house movies, so broad it becomes a live action, feature-length Looney Tunes cartoon, but nonetheless it confidently retains a melancholy undertone – which certainly shouldn’t work as well as it does. Even veterans of outré Japanese pop culture, who have sampled Takashi Miike and hentai anime and TV game shows, will find House to be pretty unique. Your appreciation may depend entirely on how much sugar you can handle; the film is like snorting Pixy Stix while dancing in a graveyard. And House is horror as pop music – songs here provided by Godiego, who also wrote the theme song of Galaxy Express 999 (1979), and who make an in-film appearance. House is avant-garde, as experimental as anything by Kenneth Anger or Stan Brakhage. It’s disturbing and accessible. It’s more dream-like than all those movies I usually call “dream-like” – one idea leads to another leads to another, so that you quickly forget how you got where you are. You have to keep up with Obayashi. He never stops fiddling with the film you’re watching.

Schoolgirls embark on their summer vacation. A matted background makes the composition look like a manga.

Obayashi proposed House to Toho based on ideas provided by his young daughter (a contemporary American equivalent might be Axe Cop, which began life as a comic book illustrated by artist Ethan Nicolle from stories told by his 5-year-old brother). Obayashi and screenwriter Chiho Katsura (who later worked on the screenplay for Rintaro’s anime film Harmagedon) took the images and ideas from Obayashi’s daughter and stitched them together into a story, applying further layers and themes (including Auntie’s WWII backstory). The script languished, even though a soundtrack, a novelization, a late-night radio play, and other spin-offs were released prior to the film’s production. The radio play’s popularity finally persuaded Toho to move forward with the film, and Obayashi, who had made the short “Emotion,” the experimental feature Confession (1968), and hundreds of television commercials, was hired to direct. The result is a film that is essentially an adaptation of itself, made for an audience already familiar with its story and music – a House based on a House based on a House. Perfect for a film that’s about as meta as a film can get. During shooting, Obayashi’s focus, it seems, was to maintain the freeform spirit of his daughter’s ideas by working without storyboards and constantly experimenting with styles and special effects. Toho, perhaps mystified by the story, gave him free reign on its vast soundstage – the delightful result was the proverbial inmate running the asylum. Most of his young cast members were amateurs, but, as the director notes in his interview on the Criterion disc, they could be guided in their performance and movements by playing the House soundtrack on the set. “They belonged to a younger generation that found it easier to express emotion through chords, melodies, and rhythms than through words. So instead of talking, I decided to use music to direct their movements. That’s how I drew performances out of them. Film critics belittled their acting for that reason, but young audiences found it interesting that the girls moved as though they were dancing.”

Kung Fu (Miki Jinbo) in action.

Photos of Obayashi on set show the director as a buoyant, bearded, sunglasses-wearing satyr of cinema, the cast gleefully following his lead. “I didn’t care if I was ridiculed. I wanted to make a film unlike any Japanese film before it…Should I shoot this scene like this? Wait, Kurosawa did something like that. No, Ozu did something similar. If Kurosawa or Ozu were to see it, what kind of direction would offend them the most?…That’s how I’ll do it.” He also took responsibility for the visual effects with his cinematographer Yoshitaka Sakamoto, shunning the professional FX artists of Toho. He didn’t want the fantastic elements to look polished. He wanted the seams to show. The crew threw themselves into the untested experiments. Actresses would be shown to dissolve by splashing buckets of blue paint over their bodies against a bluescreen. Even the most complex and challenging effects in the film were improvised with a minimum of planning. Obayashi says, “I would imagine in my mind, ‘If I shoot a reflection in a mirror, and then break the mirror, I could make composites using the cracked pieces.’…I want to make the special effects a child would make.” It was impossible to see what the end result would be until the film was printed. Every aspect of House was a dive off the deep end.

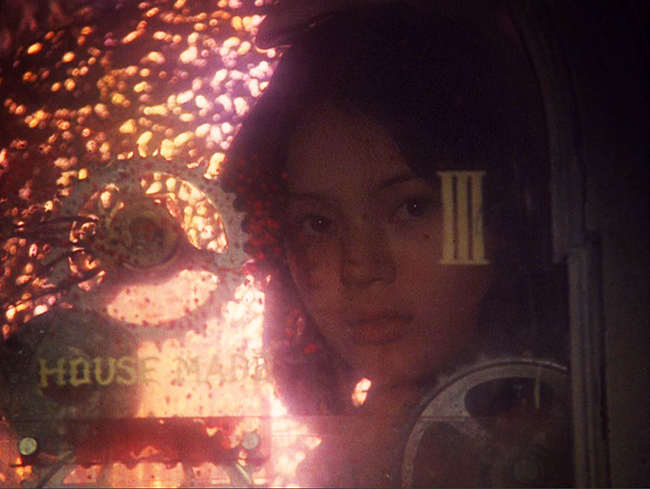

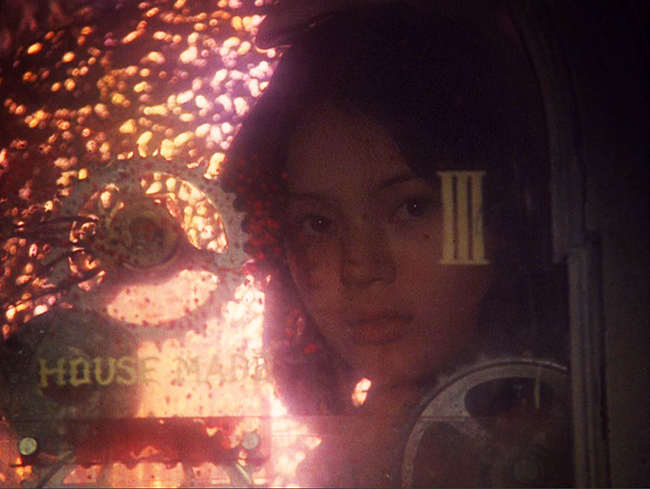

Gorgeous (Kimiko Ikegami) is consumed by the mirror.

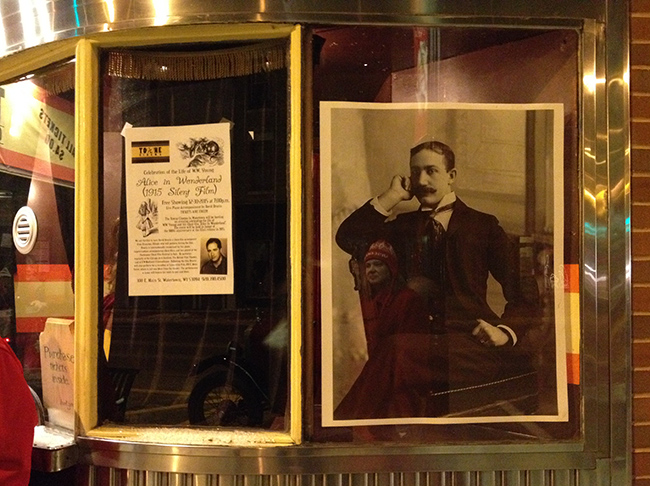

House was a box office hit in Japan, the young audience able to plug into its unique vibe even if critics could not. But it didn’t make it overseas until Janus Films acquired the film and distributed a short repertory run from 2009-2010 in advance of the Blu-Ray release. I was lucky enough to catch House in a Madison theater in 2010. The film played for a week at a venue called the Stage Door, located in the back of Madison’s landmark Orpheum Theater. The Stage Door was obliterated when the Orpheum was remodeled a few years ago, but it was an interesting place to see a movie – it would screen those films not big enough to warrant the main theater. Inevitably you wouldn’t have enough leg room. It was as cold as a meat locker. On the ceiling there was a mysterious hole, like one of the dark portals in David Lynch’s Inland Empire. When I saw a revival of Godzilla (1954) there, kids could be heard playing in the balcony. It was like some cinema netherworld – and so the perfect place for House, a movie that might as well have descended from the interdimensional hole in the ceiling. I’ve seen the film four times now, and I’m still noticing little moments – certainly on that first viewing it was way too much to absorb. There’s simply too much going on in the frame, too much flying at you with every jarring edit or multi-layered special effect. This is a House you have to revisit many times to fully appreciate. But the effect of that first immersion in Obayashi’s insane universe is irreplaceable. You’re pummeled, and it’s great. The opening shot dazzles with an effect that’s over so quickly that I didn’t fully appreciate it until this most recent viewing. House begins with a literal film-within-a-film. Gorgeous (Kimiko Ikegami) and Sweet (Masayo Miyako) are shooting a student movie, which is composited in the foreground over a frozen frame of the classroom in the background. As the movie turns to color, its lead removes her costume and walks through the classroom, and the superimposed film seamlessly joins the background, the frozen frame un-freezing. The transition happens so smoothly that it’s a wonder it was done without the aid of computers. But this is a film full of magic tricks.

The film’s opening shot, in which the film-within-a-film seamlessly merges with the background.

Gorgeous, the central character, soon meets the new fiancée (Haruko Wanibuchi) of her widower father (Saho Sasazawa). In one of the film’s best running gags, the woman is constantly shown with wind whipping her hair and scarf dramatically, a beatific, insipid smile on her face. Gorgeous, overwhelmed, decides to spend her summer vacation in Karuizawa at the home of her Auntie (Yoko Minamida). This decision comes just as a mysterious white cat, Blanche, appears at her window. Blanche will subsequently appear on the train (the cat apparently bought its own ticket), and in the lap of the wheelchair-bound Auntie – in one scene, visibly tossed into Auntie’s lap from an offscreen crew member. Along for the ride are Gorgeous’ six friends, who round out Obayashi’s version of the Seven Dwarfs: Sweet, Fantasy (Kumiko Oba), Melody (Eriko Tanaka), Prof (Ai Matsubara), Kung Fu (Miki Jinbo), and the eating-addicted Mac (Mieko Sato). If this is a Walt Disney homage, it’s not the only overt cinematic reference. Gorgeous’ father is a film composer back from Italy, boasting that “Leone said my music was better than Morricone’s.” On the train ride – which is filmed like a live action Yellow Submarine – there’s a prominently placed copy of Denis Gifford’s 1973 book A Pictorial History of Horror Movies. A shot of one girl trapped within a clock is very similar to the ghost at the window in Mario Bava’s Kill, Baby, Kill (1966). Whenever Kung Fu springs into action, the film becomes a martial arts movie, scored with the character’s groovy action theme. One of the first supernatural incidents is the severed head of Mac flying out of a well and through the air, an image straight out of Japanese ghost movies – although in Obayashi’s version, the ever-hungry Mac bites Fantasy on the rear end and proclaims, “Tasty!” All of this is scored by Asei Kobayashi with a theme that plays over and over, in different variations and styles, so incessantly that one wonders if Obayashi was trying to drive the audience to the brink of madness. There is one scene in which the theme on the soundtrack is interrupted by the theme played on a music box, followed by Melody playing it on piano. It’s enough to make you beg for another of the film’s pop songs by Godiego, just to get the demonic tune out of your head. Kobayashi also cameos as a watermelon vendor, who becomes so frightened at the implication of bananas that he becomes a skeleton and drops to the ground in pieces. Yes, that happens too.

Death by piano: severed fingers, goldfish bowl, lightning, commentary by floating head.

While Auntie frolics in the house with a dancing skeleton and chomps on eyeballs (an image mimicked in the animated opening titles, with the “O” in House biting down on one), the girls find themselves isolated, hypnotized, and absorbed into features and furniture of the house – which is haunted by Auntie’s grief over her fiancé lost during wartime. Mac becomes a watermelon to be sliced up and eaten by the unwitting girls. Sweet is assaulted by a mattress. In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, Melody, the musician of the group, is chomped up in the jaws of a possessed piano while her friend goes cross-eyed in fear, goldfish in a bowl swim through the foreground, and lightning strikes for no reason other than it’s just another thing. While Melody’s severed legs kick out of the piano’s interior and fingers plink against the keys (that musical theme will never cease), eventually Melody’s disembodied head floats into the screen, notes the camera’s leering crotch-shot, and accuses the film of being “naughty.” It’s not the only example of the characters explicitly commenting on the film. The sepia-toned WWII flashbacks are presented like 16mm film running through a projector and framed in the image as such, while the girls comment on the silent-film romance: when a kiss between Auntie and her fiancé is interrupted by a hole burning into the film, one of the girls says, “A kiss of fire!” Later, after one of Kung Fu’s many ludicrous action scenes – battling logs flying through the air and stripped down to her panties – she sagely notes, “This is ridiculous.”

Mac (Micko Sato) returns to haunt Fantasy (Kumiko Oba).

Riding to the rescue is a teacher the girls somehow find to be a dreamboat, the dopey Mr. Togo (Kiyohiko Ozaki), but Togo proves to be about as effective as The Shining‘s Scatman Crothers. He eats noodles, he gets lost, eventually he turns into a pile of bananas. Meanwhile, as the girls are offed one by one, the house fills with blood vomited from the painting of the ubiquitous demon cat. Washing up on the shore of the staircase is the final castaway, Sweet, who, in her trauma, is reunited with Gorgeous waiting on the steps, now fully possessed by the spirit of her Auntie. It’s a tribute to Obayashi that the shot of Sweet resting her head on Gorgeous’ naked breast is oddly moving (while, of course, maintaining the film’s exploitation stylings). Perhaps it’s because he’s tapping into that potent archetype of so many Japanese ghost stories and horror movies, the spirit of the wronged woman, nobly keeping house. But the epilogue, in which her father’s still-windswept fiancée arrives to find the spiritually transformed Gorgeous, is muted, even as Gorgeous consumes her stepmother in flames. The resolution is like an ellipsis; the audience – who, in 70’s Japanese cinemas, might have already consumed the story through its pre-release adaptations – is left to color in the rest of Obayashi’s violent, sexy, absurdist comic book/pop song/juvenile melodrama/surrealist happening.

Watch it late at night.