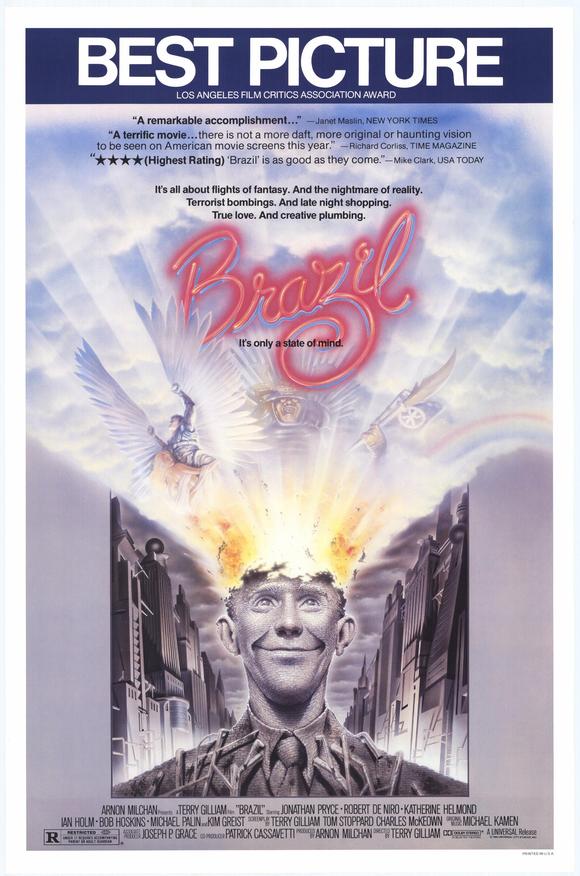

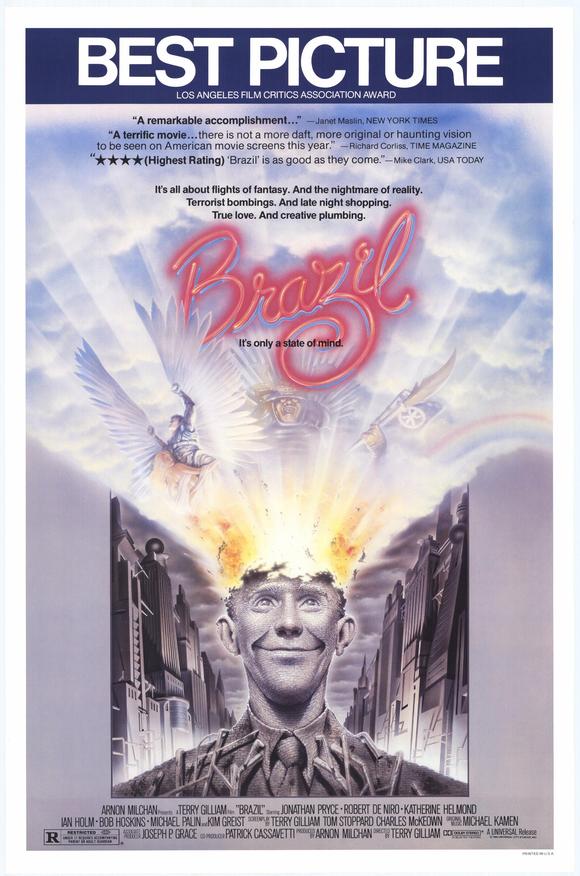

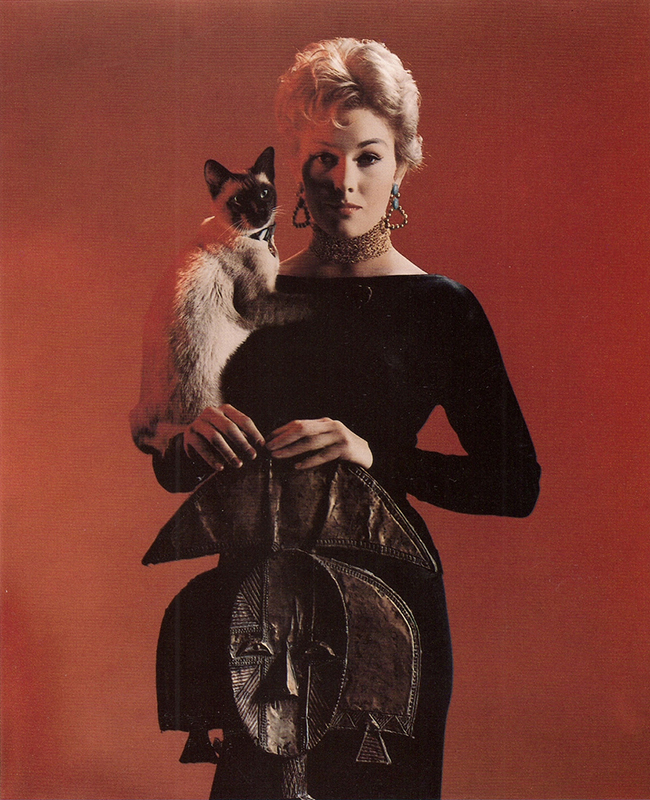

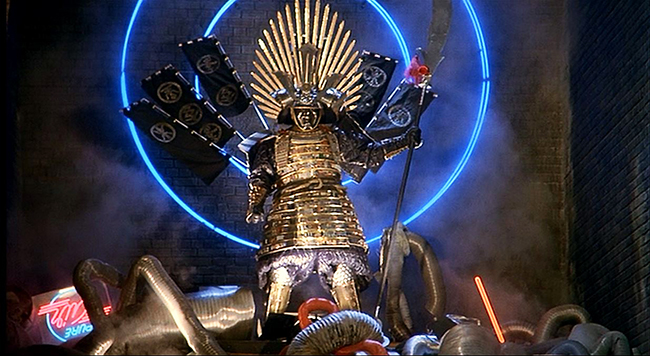

The most well known poster for Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) – at least, the one that became such a familiar video store staple in the 80’s and 90’s – is of the top of a man’s head exploding while he smiles dreamily. Out of his cranium come a silver-winged man, a samurai warrior, the red-neon title, and a blue sky that contrasts sharply with the gray urban landscape where the dreamer physically dwells. This film, Gilliam’s fourth (including his co-directing with Terry Jones on Monty Python and the Holy Grail), was his own head exploding, a mad jumble of invention and visual ideas that he’d been stockpiling in his notebooks since the mid-70’s. Somehow, miraculously, it all plays in harmony – a samba to the tune of the 1939 Ary Barroso standard “Brazil” – but it is relentless. Not a moment passes in the film that isn’t layered with two or three ideas at once, all competing for the camera’s attention. Add two more layers: the dialogue featuring contributions from famed playwright Tom Stoppard (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead), and an ambitious score in which composer Michael Kamen (The Dead Zone) twists and turns “Brazil” into variations that are blissful, bittersweet, ecstatic, fascistic, mournful, or nightmarish. It’s the darkest of satires, but so handsomely mounted that Universal thought they could turn it into a mainstream hit, and fought with Gilliam over the final cut in the studio’s misguided effort to create a film that it was never meant to be. Instead it became a cult movie, and in that vein one of the most influential of the 80’s, as well as the film to which Gilliam is still most closely identified. Like that catchy samba number, it’s become his signature tune.

Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) dreams himself the winged hero of his own film within the film.

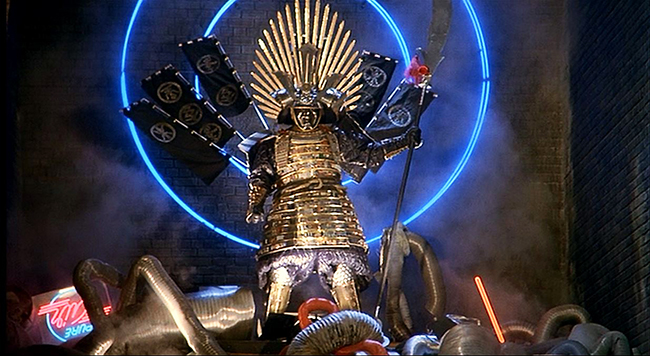

“Somewhere in the Twentieth Century,” Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce, Something Wicked This Way Comes) is quite content to keep his mid-level office job at the Department of Records in the Ministry of Information, the government entity which dominates this British realm (not Brazil – the film is named for the song, not the place). He daydreams constantly, envisioning himself as a silver-winged hero soaring through the clouds, always seeking to rescue a beautiful woman (Kim Greist, Manhunter) in a fluttering gossamer shroud, and battling strange entities including the poster’s mechanical samurai. Meanwhile, he tries to reassure his nervous wreck of a boss, Mr. Kurtzmann, that he won’t be accepting any promotions anytime soon. Kurtzmann is played by Ian Holm, who previously portrayed a Napoleon with an inferiority complex in Gilliam’s Time Bandits, and here he perfectly encapsulates an immediately recognizable sort of helpless, desperate, small-minded member of middle management. (It’s not a hostile portrait, actually, but a sympathetic, gently amused one; Gilliam even named him after his artistic mentor, Harvey Kurtzman.) Lowry ultimately will accept a promotion, but only after a series of events that perfectly illustrate the ruthless function and malfunction of the Ministry of Information. In the opening scene a fly gets caught in a printer deep in the M.O.I. offices, causing an arrest warrant for Harry Tuttle – rogue heating engineer – to accidentally print Buttle. And so one family gathering – the Buttles reading A Christmas Carol – becomes a traumatic event when Dad is bundled into a canvas sack, accused of being a terrorist, and whisked away for the discreetly phrased, utterly ominous “information retrieval procedures.” For which he’s subsequently overcharged. (In this efficient society, citizens are charged for their own torture – a detail which Gilliam borrowed from a history book about witch trials.) Sam discovers the erroneous charge as well as the fact that Buttle is listed as deleted – dead. Kurtzmann is distraught: how can they refund Buttle if he’s dead? How can they process the refund check? Sam reassures him that he’ll deliver the check himself. And it’s there, while explaining with frustration to Buttle’s widow that he’s doing her a favor by showing up in person to hand her the refund, that he glimpses his dream girl made flesh (Greist again). In an effort to learn more about her, he accepts the promotion and ascends to the upper echelons of the Ministry of Information, only then beginning to question the heartless mechanics of the society that he helps operate, the words of Mrs. Buttle echoing through his nightmares: “What have you done with his body?”

Sam explains to Mrs. Buttle (Sheila Reid) that her dead husband has been overcharged for his interrogation.

Everyone in Brazil is adept at shifting blame, even the man who, we learn, actually killed Mr. Buttle, Sam’s good friend Jack Lint (played by Gilliam’s Python cohort Michael Palin), an M.O.I. interrogator. “It wasn’t my fault that Mr. Buttle’s heart condition didn’t show up on Mr. Tuttle’s file,” Jack quite reasonably explains. He was simply given the wrong man for information retrieval, not a terrorist but a loving husband and father. It’s the system which short circuited, that’s all. And everything in Brazil short circuits, to the point that you could make a drinking game of it: the Rube Goldberg devices meant to automatically prepare Sam’s breakfast; the elevator that delivers Sam to the wrong floor, an Out of Order sign hung on it while he’s still inside; the heating system in Sam’s apartment, which prompts his introduction to the real Archibald “Harry” Tuttle (Robert De Niro), who shows up to fix things without the proper paperwork and thus finds himself on the government watch list. When Sam begins to suspect that his dream girl might actually be a terrorist, she responds, “How many terrorists have you met, Sam? I mean actual terrorists?” Tuttle hardly seems to qualify – although he does sabotage some proper heating engineers (including Bob Hoskins) in a very nasty way late in the film. In fact, Brazil edges toward the notion that the terrorists might be an invention of the Ministry, an idea made more explicit in earlier script drafts. We do see explosions and maimed bodies throughout the film, but given that everything is malfunctioning, how do we know these aren’t just more dramatic symptoms of a mechanized society constantly in a state of malfunction? In Ian Christie’s book Gilliam on Gilliam, the director says, “Are the terrorists real?…I don’t know if they are, because this huge organization has to survive at all costs, so if there is no real terrorism it has to invent terrorists to maintain itself – that’s what organizations do… Was the explosion in the restaurant a terrorist one?…It might just be part of the system that went bang, which happens all the time. But if you assume that technology works, then, if it blows up, it must be because someone blew it up…”

Mr. Helpmann (Peter Vaughan) offers Sam some advice for his upcoming torture.

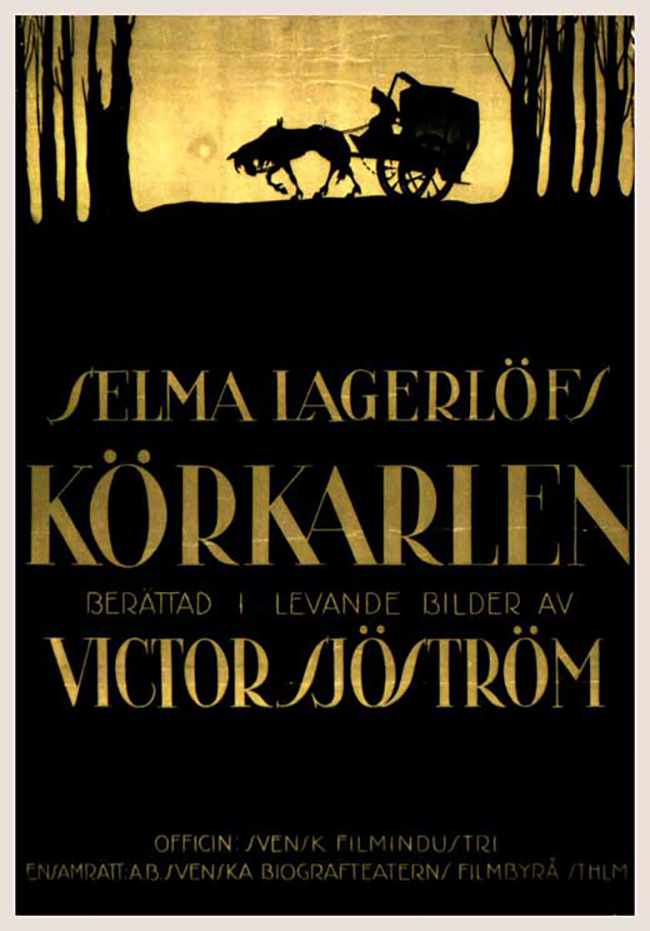

Thus there is no Big Brother in Gilliam’s Brazil (the director readily admits he hadn’t read George Orwell’s book when he set out to make this film, originally entitled 1984½). There is no Big Bad, not even the cheerfully terrifying Jack Lint, not even Mr. Helpmann (Peter Vaughan, Time Bandits, Game of Thrones), the fatherly Deputy Minister who accuses terrorists of “bad sportsmanship”: “They just can’t stand seeing the other fellow win.” There is a more existential threat in Brazil: the ducts. Ducts invade every home, every corridor; they quite spectacularly intrude upon the glamour of an upscale restaurant, diving into its central fountain. A television ad sells ducts in every color, whatever best suits your living space. The ducts of Brazil are both innocuous and nefarious, because they are omnipresent, robbing tableaus large and small of their beauty. In Sam’s dreams, he glides through an endless world of cotton clouds and golden sky – not a duct in sight. But skyscraper-like pillars erupt from the earth, barring his path, and eventually he is drawn down through their avenues, back into the ugly city again (the samurai, tellingly, stands astride a giant pile of ducts, king of the hill). The ducts deliver climate-controlled air, but also raw sewage and pages and pages of “pape.” Jack Lint, Sam Lowry, Mr. Kurtzmann, and Mr. Helpmann are just part of the ductwork, really: functional, and functionally destructive. They run on neatly processed files, efficiency at human cost – right down to Sam’s new office at the M.O.I., which has recently been cut in half for the sake of cramming another employee onto the floor. That paper-pusher (co-screenwriter Charles McKeown) pulls their shared desk through the wall, initiating a surreal tug-of-war. Sam’s first real rebellion comes in that cramped office, when he joins two pneumatic tubes together, the In and the Out, exploding those damned ducts and sending a glorious shower of paperwork over the heads of his bemused co-workers.

Samurai, neon, and ducts.

Adding to the many dense visual layers are a series of propaganda posters hung in offices and the sides of buildings or displayed on billboards (which stretch, end to end, across the countryside, obstructing any view of it). “Suspicion Breeds Confidence.” “Regret Nothing – Report Everything.” “Loose Talk is Noose Talk. Be a Live Patriot, Not a Dead Traitor.” “Don’t Suspect a Friend – Report Him.” “Trust in Security.” “Happiness: We’re All In It Together.” That last one is graffiti-modified in the slums to read: “The Shit: We’re All In It Together.” As Sam strides through a grimy back street, more graffiti is painted behind him: “Reality.” It’s a less than subtle reminder that Sam’s dreams are hiding him from the real meaning behind the M.O.I.’s sloganeering, the darkness behind “information retrieval,” the fate of Mr. Buttle. When I was a teenager, I identified absolutely with Sam Lowry – a dreamer, perpetually infatuated. Now that I’m older, and realizing that my day job has become a career, I worry that I’m turning into Mr. Kurtzmann. (There have been symptoms.) And I find myself much more frustrated with Sam Lowry, whose declaration of love to Jill Layton minutes after meeting her seems more infantile than charming these days. (She’s somewhat justified in trying to run him down with her truck – this is the man who just tried to deliver a refund check to Mrs. Buttle and became impatient when she didn’t appreciate his efforts.) Sam’s ultimate fate is tragic, it’s true, but that’s not to say he doesn’t shoulder his own blame for the sadistic bureaucracy. Interview by Bob McCabe in Dark Knights & Holy Fools (1999), Gilliam said of Sam Lowry, “He’s the guilty party. He is the system. He is what goes on. He’s been living in this sheltered little world. He’s an outrageous character. He’s got all the privileges through his father and [mother’s] connections. He’s bright so he should be taking responsibility in that organization, but he shuns responsibility. He lives in his little fantasy world. Then he goes out and delivers the check to Mrs. Buttle because it’s Christmas; it’s his good deed.”

Sam fights for his share of the desk in the office that’s been divided in two.

As Sam, the versatile Pryce gives a career-high performance. He was older than Gilliam originally envisioned the role (Tom Cruise was briefly considered, but was turned down because he wouldn’t give a screen test), yet he projects youthfulness, as well as a Buster Keaton-like athleticism. Take, for example, the scene where he grapples with Greist in a department store, the actress hidden on the other side of a mirror so that it looks like he’s wrestling with himself – a neat symbol for his own inner conflict. Or his ability to seize to the grill of her truck with his legs up like a monkey’s. He’s at his most sympathetic when he’s in Jack Lint’s office, slowly confronting the horror of the situation: that his friend tortures people for a living while the sweet receptionist in the next room types out every wail. And it’s difficult to imagine any other actor seated in the mammoth cylindrical interrogation room (actually a power station’s cooling tower), humming “Brazil” with a distant smile on his face. Pryce would switch his allegiance from fantasist to soul-crusher as The Right Ordinary Horatio Jackson in Gilliam’s follow-up, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988). Gilliam would retroactively call Time Bandits, Brazil, and Munchausen his “Dreamer” trilogy, chronicling the dreamer in childhood, middle age, and the autumn years. Familiar faces float through the films as a repertory company: Michael Palin, Ian Holm, Charles McKeown, Peter Vaughan, Katherine Helmond. Jack Purvis appears in all three, first as one of the Time Bandits, in Munchausen as the super-powered Gustavus, and in Brazil a brief cameo role as Dr. Chapman, rival to the demented plastic surgeon Dr. Jaffe (Jim Broadbent, of Moulin Rouge and the Harry Potter films). Jaffe is determined to cut the years off Sam’s mother (Helmond) through skin-stretching and Saran wrap. Dr. Chapman uses acid, a detail borrowed directly from Gilliam’s own life: his father’s skin cancer was treated by a doctor who used a technique of acid and bandages; when acid applied to his ear began to drip free, the entire center of the ear was burned away. Gilliam told Bob McCabe, “They went to sue, because the guy had been doing this to several other people. Unfortunately my dad died before the suit had been taken care of. So that was very personal about the acid man.”

In a Freudian fantasy sequence, Pryce’s mother has become young again – and turned into Pryce’s dream girl, Kim Greist.

The high budget was accommodated by splitting it between two studios: Twentieth Century Fox contributed $6 million for control of international distribution, and Universal $9 million for the American release. When the film was completed in 1985, Fox proceeded with their release of the full 142 minute cut, including its bleak but note-perfect ending. Reviews were glowing. But Universal balked at the finished product. Gilliam had been a hot property following the unexpected box office success of Time Bandits (he was offered Enemy Mine in its wake, and turned it down to push Brazil); the fact that Universal was aghast that he hadn’t delivered a more commercial product is largely due to the changing leadership which occurred at the studio during production of the film. Now Gilliam, who had final cut, was stuck trying to convince studio chief Sid Sheinberg that his film was fit for public consumption as-is. After the studio screening, Sheinberg reportedly said, “We’ll have to sell it as the film of the decade.” Which producer Arnon Milchan took as a compliment. Gilliam, however, saw the writing on the wall – like that grim graffiti of “Reality” which Sam Lowry pointedly ignores in the film. Troubled times were ahead. Universal had committed to $9 million made in two payments, one upon commencement of production, the other upon completion. The second $4.5 was withheld on the grounds that Gilliam’s cut was longer than what was contracted. An amendment was produced stipulating that if Gilliam cut the film by just ten minutes, the payment would be delivered – however, if Universal disliked the cut, they would have the right to make further edits with Gilliam’s consultation. Gilliam signed away his final cut under pressure from Milchan to have the funding released, and ultimately shortened the running time to 132 minutes. When Milchan informed Sheinberg of this, Sheinberg’s response is telling, as reported by Jack Mathews in his book The Battle of Brazil (1987): “As I have told Terry, whenever he is ready to show the picture we will only be too thrilled to see it. In my mind I still believe that a radical change in music utilizing appropriate contemporary recordings might be important in achieving audience interest in the all-important teenage category.” Milchan and Gilliam received the payment, but clearly they were doomed.

Sam and Shirley (Kathryn Pogson).

The relationship between Gilliam and Universal deteriorated quickly, and soon Sheinberg made it clear that he was going to have his own cut of the film created, as was his right per the amendment. Gilliam was phoned, but he had no interest in making further cuts and refused to work with the studio editor. He knew the film Sheinberg really wanted, and, indeed, Sheinberg’s 94-minute cut, known as the “Love Conquers All” version, is available for your viewing displeasure as part of the Criterion set. Although it’s fascinating from an archival standpoint, using many alternate takes, it ends abruptly, wrongly, in the middle of one of Sam’s fantasies – which Sheinberg means to convince us is reality. The happy ending. No torture for our hero, and no particular point to the story. But while Brazil underwent its butchery, the desperate director resorted to clandestine, contract-breaking screenings for critics and students and publicly calling out Sheinberg on morning television (with a game De Niro at his side). Most notoriously, he took out a full-page ad in Variety: “Dear Sid Sheinberg, When will you release my film Brazil? Signed Terry Gilliam.” He knew his career in Hollywood was sailing over the edge of a cliff without a pair of silver wings, but what choice did he have? The only option was to shame Universal into releasing one of his cuts, not theirs. The efforts paid off. As a result of one of those secret screenings, the film was voted Best Picture by the Los Angeles Critics Circle, as well as Best Screenplay and Best Director. Sheinberg’s sarcastic remark that it would have to be “the film of the decade” in order to recoup their investment now gave him an out, and bending under pressure, Universal released Gilliam’s 132 minute version – a film that was slightly shorter but uncompromised. In fact, I prefer the altered final shot in the American cut of the film, a perverse and poetic juxtaposition of Lowry’s dreams and reality, and I miss it when I watch the “final cut.” For years it became difficult to see the European cut in America, to the extent that when I finally saw it in Seattle’s Neptune Theatre circa 1998 I savored every unfamiliar moment. But shortly thereafter Criterion released their comprehensive box set, and the American cut has become displaced by the version Gilliam prefers. Universal certainly lost the battle, but Gilliam would return to the studio for 12 Monkeys (1995) with Sheinberg still in the executive chair. Reportedly, they avoided one another.

Sam in the torture room.

The battle scars of Brazil are all over Baron Munchausen, which was written while the battle was ongoing. With Pryce playing the Sheinberg character, it’s truly Gilliam inside John Neville’s Baron Munchausen, surrounded on all sides by the studio’s blasting cannons and lack of imagination. He wasn’t as lucky the second time around, with a production that spiraled out of control and a minuscule release received with less enthusiasm by critics – but that’s another story (and book – check out Andrew Yule’s superb and comprehensive Losing the Light). Nonetheless, both films have aged very well. Brazil, whose retro vibe meant it was not necessarily intended to be a vision of the future, seems prescient in the post-9/11 age, where the “existential threat” of terrorism has excused all sorts of sins, from Guantanamo Bay to invasive surveillance. And there is something timeless in the film’s depiction of the inhumanity that occurs when everyone’s only concerned with performing their obligatory function. “You’re running up an enormous bill by not cooperating,” Sam Lowry is warned while being billed for his own torture. “If you hold out too long you could jeopardize your credit rating.” By dressing issues of torture and murder in back-office banality – the man’s dead, how do we get rid of this refund check? – Brazil, a “dystopian” film, accurately depicts how horror works in the everyday world. This is how fascism really operates – with paperwork and processing of files, and nervous fits when things inevitably break and the real darkness behind the system is exposed. Merry Christmas?