The runaway box office success of Cat People (1942) gave producer Val Lewton a now-legendary amount of leeway during his run at RKO. As long as he kept the spending thrifty and stuck to the sensational titles imposed by the studio, he was given carte blanche to make the atmospheric, intelligent thrillers he desired. A full two years after Cat People, Lewton returned with a sequel that displayed his brazen independence from studio-think. This time, the title The Curse of the Cat People (1944) was forcibly attached to a film that he originally intended to call Amy and Her Friend. Even if the film is a sequel only at gunpoint, it’s the sort of sequel audiences ought to get more often: not a retread, but a completely different story connected to the original in a manner both tangential and vital. Lewton, who provided a final draft to all the scripts that passed over his desk, never underestimated his audience’s intelligence. In the case of this very rare sequel, he changes not only the plot and themes but the genre. Cat People was a sophisticated adult horror film about S-E-X, slipping past the Production Code thanks to Lewton’s (and director Jacques Tourneur’s) powers of cinematic suggestion. The Curse of the Cat People is a film about…childhood imagination and parenting, of all things. No one turns into a cat. No one threatens to turn into a cat. Nonetheless, it is a sequel, continuing the story several years on and informing us of what became of the last surviving couple of Cat People, Oliver Reed (Kent Smith, returning) and Alice Moore (Jane Randolph, also returning), now the new Mrs. Reed following the death of Ollie’s cat-cursed first wife, Irena (the irreplaceable Simone Simon). In a way, we even learn what became of Irena, if only through the eyes of Oliver and Alice’s young daughter Amy (Ann Carter, I Married a Witch).

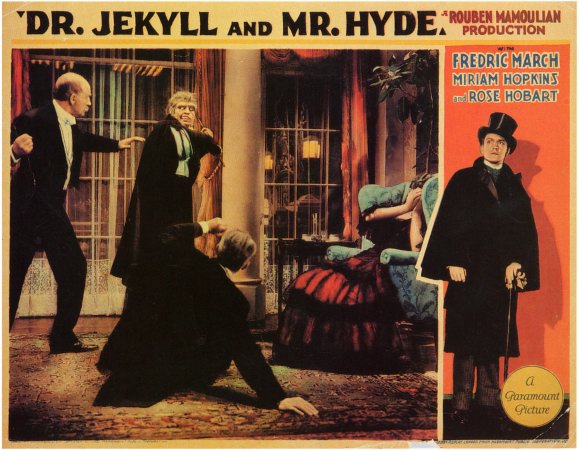

A different kind of horror: a boy’s careless destruction of a butterfly admired by young Amy.

Amy Reed can’t seem to find any friends, out of step with both the boys and girls her own age, and lost in her own imaginary world – it surely can’t be a coincidence that she looks like an Alice from an Alice in Wonderland movie. (The name “Alice” was already taken – by Jane Randolph’s character.) At the opening of the film, a teacher, Miss Callahan (Eve March, Adam’s Rib), describes the Headless Horseman while standing with her students on a bridge to cross from Tarrytown, New York, into the village of Sleepy Hollow. As the kids start to play with one another, Amy wanders off on her own, following an animated butterfly which she calls “my friend” – her refrain in the film. A boy, hoping to please her, catches the butterfly in his hands, inadvertently crushing it to pieces. This is the sort of horror that The Curse of the Cat People has to offer. Meanwhile, the girls dismiss her as strange, despite Miss Callahan’s insistence that Amy’s just “different.” At home, her misunderstanding father punishes her when she insists upon her imagination over reality, while mother pleads for patience. Amy’s latest crime is mailing invitations for her birthday party in her “magic mailbox,” a hollow in an old tree in their yard. The children further resent her for never receiving any invites, and so she finds herself wandering lonely into the thrall of an Old Dark House occupied by a reclusive former actress named Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean, herself a star of stage and silent films who was just mounting a return to acting after twenty-five years). Mrs. Farren also lives in her own illusory world, much to the resentment of her daughter, Barbara (Elizabeth Russell, Bedlam), who lives with her. She refuses to acknowledge that Barbara is her daughter, claiming the real Barbara died when she was six; but she embraces Amy and treats her as a surrogate, giving her a “wishing ring” as a present. The barest trace of a horror element is introduced at the suggestion that Barbara’s mistreatment by her senile mother might be giving her some very dark thoughts – with Amy as the scapegoat and potential victim.

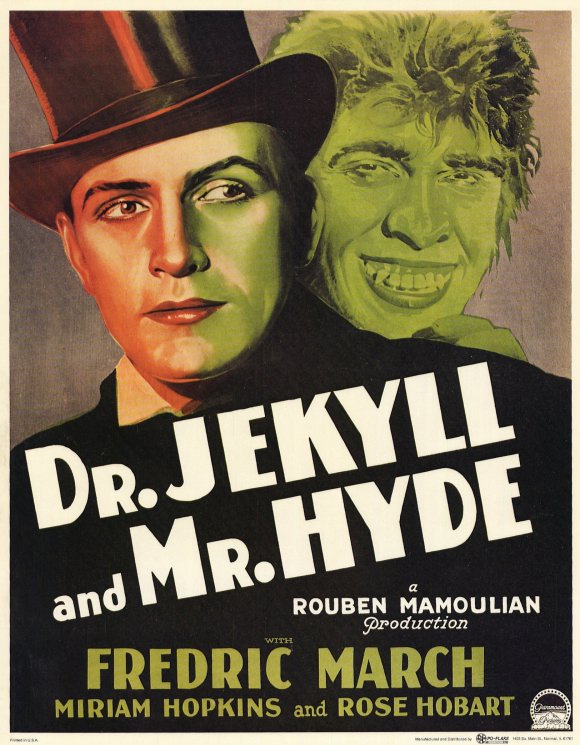

The deceased Irena (Simone Simon) offers friendship to the lonely Amy (Ann Carter).

The heart of the film comes with the introduction of Irena, who perished at the end of Cat People, undone by her jealousy of Oliver and Alice, and, of course, her “curse.” Here Amy, looking so hard for a friend, reconstructs Irena from an old photo of her father’s and the dropped name. Her Irena is the Irena we wished she could have become, if tragedy hadn’t intervened in the first film; the sexually frustrated, melancholy, envious Irena has become self-actualized – even warm and cheerful – through Amy’s imagining. She is also the only one who understands and listens to the little girl. The product of the “Wishing Ring,” she’s introduced stepping out from under the old tree and its magic mailbox, as though emerging from that other dimension through which Amy wishes letters could travel. As autumn gives way to winter – beautifully illustrated by leaves, falling like rain, becoming a cascade of snowflakes – Irena appears under the long branch of the old tree singing a French Christmas carol. But Amy’s insistence that she can see Irena further annoys and troubles her father, who, it’s evident, is haunted himself by memories of the catastrophe of his first marriage (he acknowledges Irena murdered before she was killed). And he seems to carry a good deal of guilt with him over that relationship as well, possibly blaming himself for what happened; that he keeps old photos of her, and can’t bring himself to destroy his last picture at Alice’s request, speaks of a lingering obsession. It all comes to a head when Oliver’s words drive his daughter out into the middle of a snowstorm on Christmas Eve, where she imagines the Headless Horseman chasing her (actually the rattling wheel of a car), and almost freezes to death before she faces a different kind of peril in the form of the jealous Barbara Farren.

The cats of “The Curse of the Cat People” (clockwise from upper-left): A stuffed cat with a bird in its jaws; “Irena’s favorite painting,” Goya’s “Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga,” with its lusting cats; two boys pretend to machine-gun a black cat off a branch; Amy is watched by two sphinxes on the bannisters.

Although the film is explicitly about Amy’s imagination and Oliver’s reconciliation with it, it is also about reconciliation with the past: the events of Cat People. A pouncing cat appears on the title card of screenwriter DeWitt Bodeen (who wrote the original film), and a black cat is soon seen lurking on a branch, when two boys pretend to machine-gun it – reportedly a scene demanded of Lewton at RKO’s dismay at the lack of Cat People in this Cat People movie, but also a subliminal introduction of Irena, the brutally silenced cat of the original film. A memento that belonged to Irena still hangs in the living room, Goya’s “Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga” (1787-88), or the “Red Boy,” which depicts a count’s son with his pet finch, three lusting cats lurking just behind him. In Mrs. Farren’s home, rich with the famous Lewton shadows, Amy encounters a grotesque display of taxidermy, a cat with a bird in its mouth – like the horrific aftermath of Goya’s darkly comic portrait. We can also glimpse two sphinxes guarding the stairs, a gate with a trial, a riddle, that she must pass. Sure enough, the climax takes place upon those stairs, as we learn that Mrs. Farren can’t climb them without the exertion killing her; it’s also on the stairs that Barbara threatens Amy’s life. Between those sphinxes – cat/predator, bird/victim, and woman, all as one – Amy confronts death, as Irena did, but with a happier (or at least bittersweet) resolution. There are also softer echoes to the first film, such as Alice’s remembrance of performing in “mummer’s plays” and “sword dances” and “St. George and the Dragon,” subliminally calling to mind Irena’s St. George-like statue in the first film, the Serbian King John impaling a cat with his sword. In other words, everywhere there is Irena, making this a sequel in which Cat People aren’t important, but the Cat Person is.

The Reed Family Christmas: Oliver (Kent Smith), Alice (Jane Randolph), and Amy.

Directing this time out was Gunther V. Fritsch (who had cut his teeth directing short films), but when he was perilously slowing the production, the budget climbing, Magnificent Ambersons editor Robert Wise was brought on board for his first directing credit. Wise would go on to an impressive career: The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), West Side Story (1961), The Haunting (1963), and The Sound of Music (1965), among many others. The Curse of the Cat People was actually shot on some of the same sets as Ambersons, giving it a big-budget look with ample help from a strong score by the prolific Roy Webb (who had scored previous Lewton efforts such as Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and The Seventh Victim) and lush black-and-white photography by Nicholas Musuraca (Cat People, The Seventh Victim, The Ghost Ship). Musuraca visually signals when we shift into Amy’s imagination by having an enchanted light sweep through the yard, or by showing the shadow of an unseen Irena slip from outside the window into the bedroom. But much of the credit for the film’s power lies with young Ann Carter, fantastic in her performance as Amy. (Sadly, Carter passed away last year at age 77.) Interviewed by Tom Weaver in Video Watchdog No. 137 (March 2008), she recalled, “I really was somewhat like her – a little bit of a dreamer. I enjoyed fantasy; my mother read to me so much…And I was ‘alone’ like Amy, an only child, so we were similar.” The accuracy of Amy’s depiction also depends to a great extent upon Lewton. Though DeWitt is credited for the screenplay, much is drawn from Lewton’s own lonely childhood – he, too, posted letters in a tree hollow. When Weaver asked Carter, “What happens to the Amys of the world who never get their acts together? Do they all become Val Lewtons?”, she responds, sensibly: “They may feel similarly, but just think of the amazing work Val Lewton gave us. They won’t all become Val Lewtons, because who has the talent that Mr. Lewton did?”