The most effective stretch of Burn, Witch, Burn (1962), whose original British release title is Night of the Eagle, is a long, carefully constructed, vital stretch in which Norman Taylor (Peter Wyngarde, The Innocents), an erudite university professor and a staunch skeptic, gradually comes to realize that his wife Tansy (Janet Blair, The Black Arrow) is a practicing witch. It’s unbelievable to him, not just because every day he teaches his students about the ignorance of belief in the supernatural, but because his wife, his suburban home, his friends, all seem so very ordinary. Slowly his eyes are opened, not just to the many charms Tansy has secretly planted about the house, not just to her conviction that witchcraft is effective, but to the fact that the shadowy world of the uncanny is all around him, barely kept at bay by his wife’s efforts. In fact, it is Norman who has been in ignorance, protected in a bubble that was of his wife’s making. When he asks Tansy to destroy all the charms, that bubble breaks, and the placid, easygoing success that has been their life together is suddenly threatened, seemingly from all directions, as though the world is caving in. It’s easy to imagine that these moments of Burn, Witch, Burn are what most interested screenwriters Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont; everything else, including Norman’s march into the world of witches and hexes to rescue his wife after she suffers a life-threatening supernatural attack, somehow feels a bit more flat, a bit less interesting, than those prickly conversations between Norman and Tansy in their fast-crumbling sanctuary. It’s staged as simply as a play. But Matheson and Beaumont, two of the most acclaimed writers of The Twilight Zone, milk every square foot of the living room, kitchen, bedroom, fireplace – the Taylor home is turned inside out to reveal what’s really holding up that posh house. In one moment, Tansy spins the tasseled lampshade to discover a little voodoo doll perfectly disguised amongst the tassels, and she hastily removes and burns it: the first sign that their home has been invaded by a hostile force. Or perhaps the initial sign is in the casual disappointment of Norman when he discovers that his wife believes in witchcraft: the subtle but withering disdain. As with the best Twilight Zone scripts, the fantastic is part and parcel of the mundane. We understand the stakes because we see the wedge driven into their marriage. It’s witchcraft this time, but it could have been anything.

Norman Taylor (Peter Wyngarde) discovers charms and other instruments of witchcraft hidden about his house.

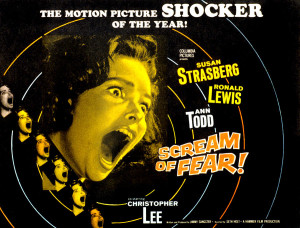

Burn, Witch, Burn is based on the 1943 novel Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber, which was published in Unknown Worlds and first reached the big screen as the Inner Sanctum film Weird Woman (1944) starring Lon Chaney, Jr. Leiber produced a rich body of work in fantasy, SF, and horror, and among his accomplishments is helping to mold the modern sword and sorcery genre with his wonderful “Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser” story cycle; he is a titan of fantasy fiction. Matheson and Beaumont resurrected Leiber’s novel, but instead of making a pulp quickie, treated the horror story with the same level of sophistication and wit as Jacques Tourneur’s classic M.R. James adaptation Night of the Demon (1957). American International Pictures outsourced the script to the British production company Anglo-Amalgamated, who distributed many AIP films, and so Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch Burn is a British film. In the director’s chair was Sidney Hayers, who made Circus of Horrors (1960), but whose career would largely be spent in television. To play Tansy, Janet Blair was cast, an American actress with a lengthy Hollywood resume and a headliner of musical theater. Peter Wyngarde, who appeared in The Innocents as the glowering face of a ghost, in this film gets quite a bit more to do as Norman. He and Blair make a convincing married couple, but nonetheless they are both a bit miscast; the script implies they are younger. Norman is supposed to be a fairly green, handsome professor over whom students swoon, and the object of the faculty’s scorn and envy – the spark of all his subsequent troubles. I would have cast the young Oliver Reed – and perhaps Susan Strasberg of Scream of Fear (1961) as his witchy wife. Nevertheless, the problem would have been exacerbated if the producers got their first choice for the role of Norman – the much older Peter Cushing! Wyngarde would later play Number Two in the classic Prisoner episode “Checkmate” (the one with the game of human chess); so it’s an added treat for Prisoner fans like myself that Burn, Witch, Burn also features Colin Gordon, the nervous, milk-drinking Number Two of “The General” and “A, B, & C.” Margaret Johnston (The Psychopath) rounds out the cast, turning in an excellent performance as the calculating, smug Flora.

Norman confronts the wicked Flora (Margaret Johnston) in her office.

The eagle of the original title is a great stone statue hovering above the university where Norman works. It’s an odd object of menace, to be sure (why not a gargoyle?), but figures memorably into the film’s climax. Most of the suspense in Burn, Witch, Burn comes not from hulking stone statues but from the invisible. It’s the sense of not knowing the rules, of having the expert – Tansy – benched while Norman tries desperately to figure out the rules. Perhaps the best moments of the eerie are produced by a recording of one of Norman’s dry lectures, tainted by a hypnotic tone that seems to be an invocation of dark forces: the perfect summation of a skeptic undermined by the evil he persists in denying. But the threats first arrive in a manner that doesn’t seem to be supernatural: Norman is accused by one of his female students (Judith Stott) of sexual assault – jarring, given that we know she was nurturing an unrequited crush on him. This, by the way, is the part of the film that’s aged the worst: the dean allows Norman the opportunity to question the student about the accusation in private (!). Ultimately Norman is given the benefit of the doubt, and the accusations are quickly recanted and forgotten about: not exactly the most sensitive treatment of the issue of campus rape. And there’s an equally dated notion behind the story that the stay-at-home wife must protect her husband’s career at all costs – the novel was written in the 40’s, after all. But as Matheson and Beaumont slowly turn the screws on Norman Taylor, we see that it’s his wife who really knows how the world works, and his carefully constructed worldview is only a house of cards scattered by witch-summoned winds. For the American release, AIP, eager to match William Castle, appended a prologue in which Paul Frees warned audiences of the film’s occult power, and at special screenings audiences were issued salt and a protective spell. One of the posters proclaimed, “SPECIAL DE-WITCHING CEREMONY PRIOR TO EVERY PERFORMANCE! The management disclaims all responsibility to those who feel they are already partly hexed and immune to our protective measures!”