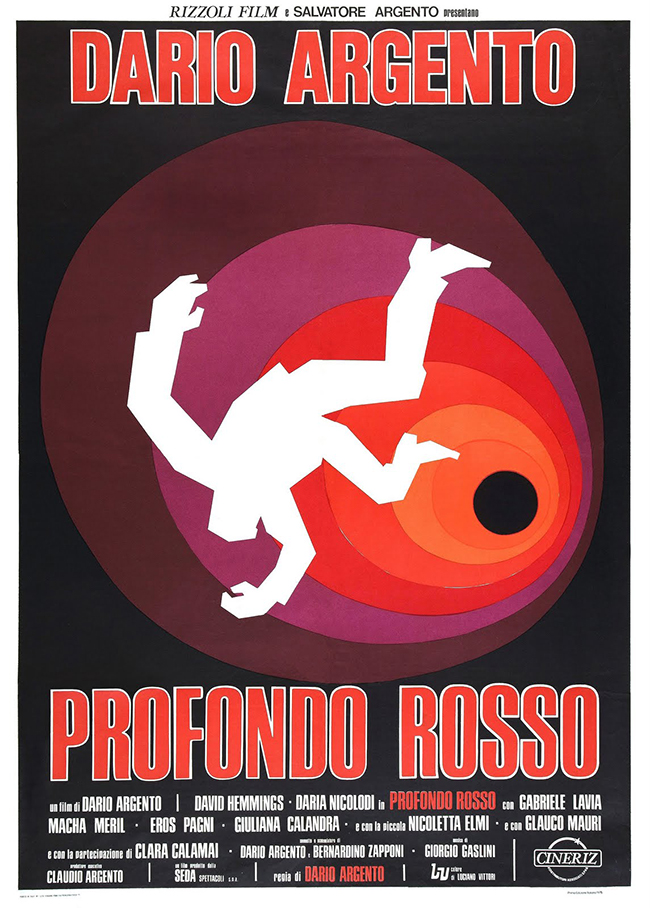

Dario Argento’s Deep Red (Profondo Rosso, 1975) is a suffocating film, as if you can slowly feel a noose tightening around your neck. Although it was not to be his last giallo, it’s perhaps his maximum giallo. It is also a horror film, although his next, Suspiria (1977), would embrace that label without compromise. You can trace Deep Red‘s lineage back to not just the “yellow” Italian pulps that inspired giallo films, but to the fetishistic, voyeuristic murders of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), Mario Bava’s stylish and colorful thrillers including his proto-slasher Bay of Blood (1971), and Argento’s own trendsetting “animal” trilogy, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), The Cat o’Nine Tails (1971), and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971). Nevertheless, Deep Red turns a corner, both for Argento’s method and the horror genre as a whole. For the score, Argento, who had notable collaborations with Ennio Morricone in his filmography, took a risk on a little-known prog rock band called Goblin. The result is a rock horror film. Not a rock musical, mind you, but a movie in which every murder becomes a choreographed performance, the elements being Goblin’s stabbing keyboards, Argento’s floating, circling camera, geysers of bright red blood, punctured flesh, and, for lyrics, the rasping voice of the killer. Style is everything. Logic is less important. Deep Red is horror cinema as a waking nightmare, as sensory overload. It lays the groundwork for the slightly better-known Suspiria, but it’s a masterpiece in its own right.

David Hemmings and Daria Nicolodi team up to solve a brutal murder.

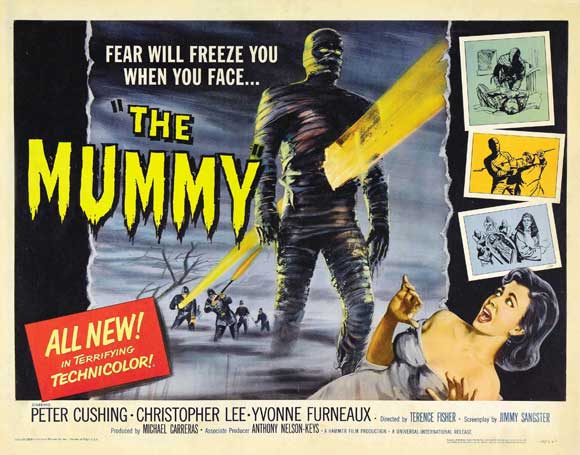

Like any good giallo, the plot is a tangled mystery with momentum sustained by its suspense scenes – and graphic killings. Our audience surrogate this time is Marcus Daly (David Hemmings of Blow-Up fame), a British pianist living in Italy who witnesses a woman’s murder. After walking down a deserted street talking with his friend and musical partner Carlo (Gabriele Lavia, Beyond the Door), Marcus approaches his apartment building and sees the upstairs window being smashed open by a woman’s screaming face. He rushes upstairs and into the apartment to discover the dead body, glimpsing the raincoat-clad killer escaping through the street below. Questioned by police, the only unusual detail is that a portrait, which he glimpsed upon entering the apartment, now seems to be missing. He also meets an ambitious reporter named Gianna (Daria Nicolodi, Argento’s romantic partner, the mother of Asia Argento, and the co-writer of Suspiria). After Gianna writes an (unhelpful) article stating that Marcus saw the killer, he believes he might be next on the hit list. This is confirmed when the killer enters his apartment, plays eerie children’s music on a tape-player, corners and traps him – and we’re only halfway through the film.

A paranormal conference, approached by Dario Argento’s roving camera through red curtains.

The plot is actually very simple, when all is revealed (and one crucial twist regarding that missing painting you’ll probably figure out right away), but that’s not really the point. Deep Red is an experience, like a theme park ride. Argento had taken a brief respite from giallo with his previous film, The Five Days (1973), and upon his return he sought to reduce the genre to its most potent elements, leaving all the boring bits on the cutting room floor. The American edit, which is shorter by 22 minutes, was actually overseen by Argento, and among the trims are many dialogue scenes. The film is meant to land like a punch. In retrospect one might wonder what’s up with that mechanical doll that struts – impossibly, terrifyingly – across the room in one shot. How does that work? Why’s it there? You might wonder why there’s a big setpiece involving psychic phenomena: at a paranormal conference, a medium onstage picks up violent thoughts from a member of the audience, and is subsequently murdered for accidentally connecting with the killer. This isn’t a film about the paranormal. Nothing else supernatural occurs in the story. Why have this? For the moment, of course. For the mini-movie it provides, with a beginning, middle, and end. For the way the paranormal conference proceeds along the banal before becoming heightened when the psychic suddenly stumbles upon the thoughts of the murderer. For the theatrical opportunities, with Argento’s camera sweeping between red curtains and down the center aisle of the grand old theater, closing the sequence with another rope-pull and the sweep of curtains. In Argentoland, everything is about the moment. If you leave the theater wondering why this and why that, it hardly matters. You might also awaken from a nightmare, describe it to a friend, and watch them roll their eyes. It was frightening to you in the moment, and the moment, in Argentoland, is cinema. Goblin’s throbbing sounds, Argento’s impeccable eye, and the build and build to an explosion of violence. One of Argento’s key contributions to horror was demonstrating how it should feel, and that feeling, if overpowering, can override all other concerns.

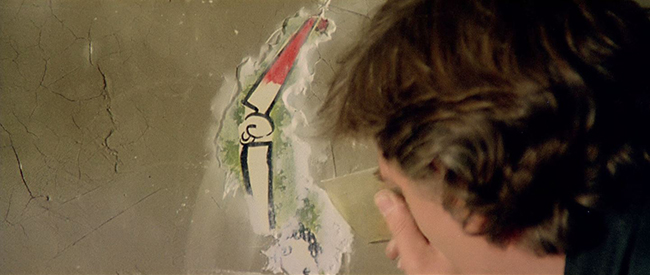

Hemmings uncovers a plastered-over child’s drawing in an empty villa.

But on this viewing I was struck by one of the film’s less-advertised qualities: it opens like a Fellini film. First there’s David Hemmings playing with his jazz combo, the epitome of cool, and then he’s wandering the empty streets (of Turin) with his friend Carlo, two young men happy in their haunted city, Argento’s camera at a great distance, emphasizing the open night. There’s even some well-played physical comedy. These might be deleted scenes from La Dolce Vita. Throughout, there are clever little moments, Argento attuned to the performance of Hemmings (he’s quite good, even though he’s essentially playing the same role as in Blow-Up) and the opportunities of physical space, but he seamlessly transitions this level of realistic physical detail into the realm of nightmare, such as when Hemmings wanders into a dark home, the site of a murder, and trips down a step, landing next to a fallen birdcage and a dead bird. He touches the cage. He wipes his hand. These are minor details compared to the operatic, attention-grabbing murder scenes, but the viewer registers even these smallest gestures, like the wiping of the hand, unconsciously. It’s an experiential film. The audience is present in that room. Argento was careful to stage the murders with physical injuries that the audience could understand. One of the most painful, for me, was watching one victim get his teeth slammed repeatedly against the corner of a table. Because it was so easy to imagine accidentally falling and smashing my mouth against a table’s edge, I could almost feel this. And Argento knows that – he looks for pain that can reach out from the screen like a 4-D movie. There is a vivid, inescapable atmosphere to Deep Red, even in that brief shot of the “painting,” the woman’s face, that Hemmings sees in his fateful first visit to the woman’s apartment. It is dropped into the corner of the screen like a clue, but also like a shrapnel of nightmare lodged into the film from the aether of our unconscious. He would push this further, to great success, in the overtly otherworldly Suspiria. But in Deep Red the elements of nightmare are already assembled, an apotheosis of dread, and the shrapnel stays with you.