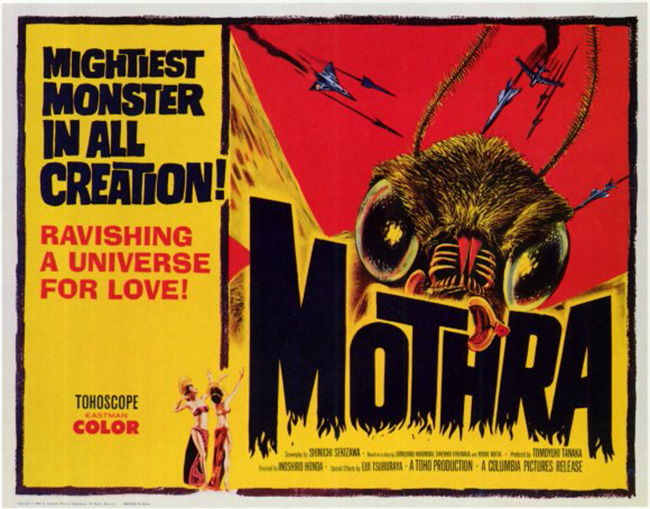

Mothra (1961) was based on a Japanese novel (The Luminous Fairies and Mothra) but regardless takes its biggest cues from the earlier Godzilla films (Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again) and King Kong (1933). As in King Kong, the plot is set in motion by an expedition to a remote (Polynesian) island, isolated from modern civilization and teeming with exotic dangers. Among these are a “vampire plant” and a tribe of natives prone to elaborate dance numbers. But most mysterious are a pair of fairy twins only a foot high, played by the “Peanuts,” singing sisters Emi and Yumi Ito. They’re abducted by the egomaniacal villain (Jerry Itou), who exploits them in a stage show, introducing them in the English dub as a “wonder of the world.” (The eighth wonder was already taken.) After forcing the pair to sing their hymn to the mysterious “Mothra” before a backdrop resembling a cut-out version of their island home, he keeps them imprisoned in a birdcage backstage. For a good half of the film, Mothra is nothing more than a giant egg which the natives keep hidden. But after the fairies’ abduction, the egg hatches and a great caterpillar is unleashed, swimming to Japan and sinking cruisers on the way.

Mothra, in caterpillar form, leaves destruction in her wake.

One of the nifty kaiju aspects of Mothra is that she (and it is a she) is two monsters in one, a trick repeated in subsequent films. Director Ishirō Honda (Godzilla) makes the most of both the caterpillar and moth manifestations of Mothra: as a caterpillar she bursts through buildings, and as a moth the powerful beat of her wings sends (toy) cars hurling through the streets. And Mothra isn’t a man (or woman) in a suit, but a puppet, giving this monster picture a touch unique from its brethren. As with a lot of the kaiju films, the special effects run hot and cold, but on the whole are impressive for 1961. A shot where Mothra the caterpillar rears her head through a flaming sea looks unexpectedly convincing. The matte paintings, in particular during the early exploration of the island, add a necessary touch of wonder, not unlike those spectacular paintings in King Kong – if only there were more of them. Some of the miniature effects are impressive-looking, although by the climax the illusion of scale degrades quickly. Not that you watch a kaiju film for realism. For that, look to the first – and best – Godzilla (1954). That film was a grim, gritty parable about the perils of the atomic age, with heavy overtones of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Seven years on, Ishirō Honda lightens the mood with Mothra. Not only does he give the main role to a comedian (Frankie Sakai) – who, let’s face it, is pulling faces through the entire picture – but this full color, widescreen Tohoscope fantasy emphasizes the surreal beauty of monsters.

The foot-tall fairy twins (Yumi and Emi Ito) perform for a greedy impresario.

The most visually stunning, eerily strange example comes midway through the film, when the twins are engaged in their stage act, which involves floating above the audience is a miniature carriage strung on a wire. The hovering coach moves against a painted night sky – the walls of the theater, with artificially twinkling stars – but for a moment is superimposed over the turbulent ocean waves. Then Mothra, like a torpedo, bursts over the horizon, eyes aglow, as the carriage passes by, and the girls sing at her; she seems to be following the flying carriage like a loyal dog. When Mothra finally becomes a moth, it’s not a terrible, ugly creature, but colorful and lovely (and ludicrous, all at once – by now the illusion of scale is completely gone, as the little fluffy puppet flaps its way across the set). Kaiju destruction always wears out its welcome early, but Mothra doesn’t linger too long for the action to become banal. Refreshing for a monster movie from 1961, Mothra doesn’t succumb to fiery death, but flies free after being calmed by the knelling of bells and a sacred, cross-like symbol recreated from her island temple – as well as the soothing telepathic influence of the two fairies. In other words, in Mothra it’s enough that the monster stops destroying buildings and cars. We all know she’s misunderstood; now let her loose, sequel-bound. No wonder the film proved a hit with Japanese girls, and so Mothra took a bow for her follow-up films, including the entertaining, and inevitable, Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964).