Imagine that there were no sequels to A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), no endless stream of Freddy Krueger merchandise, no Freddy vs. Jason, no parodies even after the series itself had become self-parodying, no 2010 reboot or the many reboots to come. Imagine there was just A Nightmare on Elm Street. The success of the film was Freddy’s worst enemy, in some ways, and even though we periodically return to the Elm Street universe, and filmmakers try to make Freddy scary again, he’s already ascended to the pantheon of classic monsters, overshadowing the film that birthed him. He’s a wax figure now, a Halloween costume, a Simpsons drawing. He shows his glove of knives, tips his dirty hat, lounges in his red-and-green sweater, the scars on his burned face as familiar and unfrightening as the neck bolts of Frankenstein’s monster. But imagine there was just this film, a mid-career jolt of inspiration from the late, great Wes Craven, who had previously given us the unsettling grindhouse classic The Last House on the Left (1972), plus The Hills Have Eyes (1977), Deadly Blessing (1981), and Swamp Thing (1982). By 1984, the slasher craze was beginning to feel a little tired. The Friday the 13th series was already releasing its “Final Chapter” (spoilers: it wasn’t). Nightmare was a second wind for the genre, kicking off its next wave. What was significant was not the arrival of Freddy Krueger but of A Nightmare on Elm Street, a near-perfect slasher film, impeccably assembled, cleverly scripted and plotted, that happens to have – pre-Scream – a winking appreciation for genre tropes without for one second undermining the suspense. If you can strip away everything that came after and watch Nightmare with fresh eyes, it’s easy to understand why the film made such an impression.

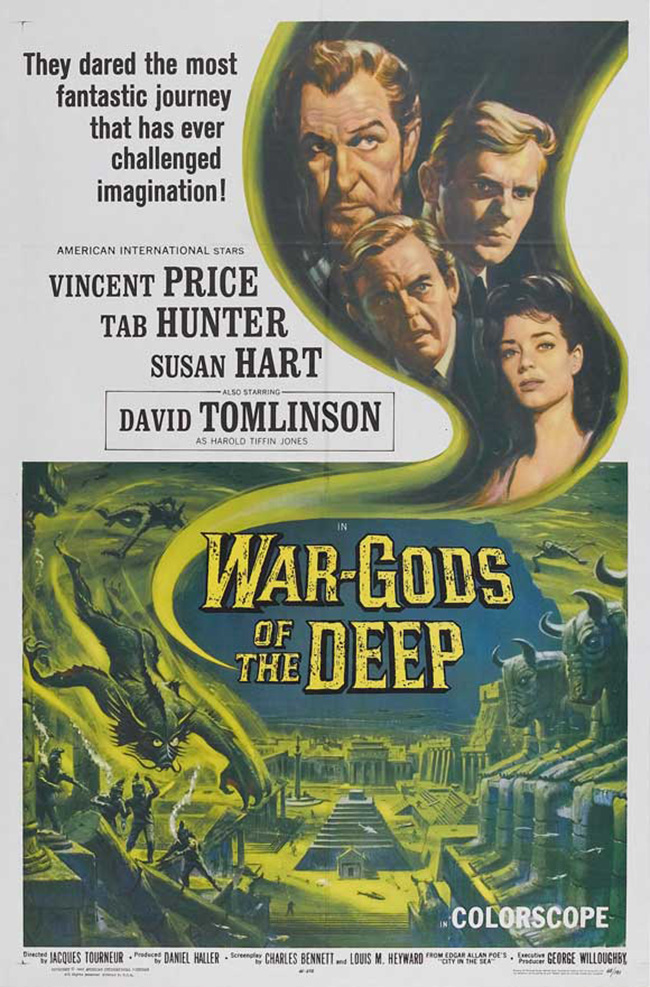

Heather Langenkamp as Nancy Thompson.

Foremost is not Freddy but its premise: if you fall asleep, you die. So there is no rest for the characters living on Elm Street. In their nightmares, Freddy comes for them. This gives the film a relentless, exhausting quality, the actual horror. Many of the best horror films give the audience something tangible to which they can relate. What would I do if that happened to me? How would I stay awake, and for how long could I do it? Here is something everyone, without exception, can understand: the biological need for sleep. With that stripped away from Craven’s teenage protagonists, there is seemingly endless material for a horror film, a playground for Craven’s imagination. (It’s telling that Craven had to step in and provide a story for the third film, saving the franchise after it seriously stumbled in its sophomore outing. 1987’s A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors is the imaginative, fun sequel that the original deserved.) But it takes a while, naturally, for the characters to figure out exactly what’s going on. Being an original film, Nightmare has the luxury of discovery – for its characters and the audience. It opens with a dream of young Tina’s (Amanda Wyss, John Cusack’s obsession in Better Off Dead). In an underground boiler room, a sheep wanders through the frame (was she counting them?). Then Tina stumbles upon a scarred boogeyman in a hat and striped sweater, and sporting a glove with knives on its fingers. Listen close: on the soundtrack you can hear the baas of a flock of sheep. He chases her, slashes with his glove, and she awakens to find that her nightgown has been shredded. This is our first indication that the boogeyman is not just confined to the realm of dreams.

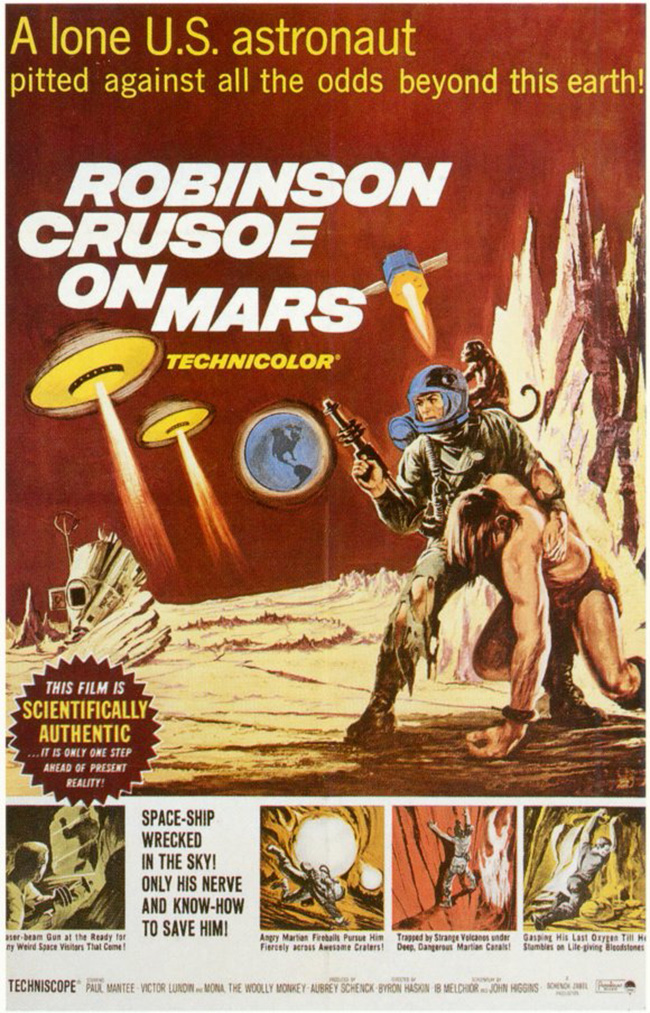

Johnny Depp as the boyfriend, Glen.

“Maybe we’re gonna have a big earthquake. They say things get really weird right before.” It’s the morning of another school day, and our cast of high school students pile into a car: Tina, her friend Nancy (Heather Langenkamp), and Nancy’s jock boyfriend Glen (Johnny Depp, pre-everything). We also meet Tina’s boyfriend, the leather jacketed greaser Rod (Jsu Garcia), the type who seems to be up to no good, but actually has a heart of gold. Everything seems to be lining up to slasher movie tradition: Tina and Rod have an active sex life, and Nancy – a brunette – seems to be the virginal “Final Girl” type. And, indeed, Nancy is the Final Girl. But Craven cuts to the chase quickly. Less interested in a body count, he keeps his cast small so he can focus in on the details of teenage suburban life, and how their interest in the trivial quickly escalates into something far more earth-shattering, something their parents can’t understand and refuse to believe. Tina isn’t long for this film. Her death scene is a showstopper. While the Friday the 13th films were obsessed with creative kills (what sharp object can penetrate where), Craven is thinking outside the box. Or, rather, he turns it upside-down. That’s what he does with the bedroom set, when he has an invisible Freddy drag Tina kicking and screaming to the ceiling, slashing her chest again and again, then dropping her, pools of blood everywhere while boyfriend Rod stares at the carnage impotently. He flees the scene, because in this locked room he’s the only suspect. Nancy’s dad, police lieutenant Donald Thompson (John Saxon, Enter the Dragon), sets a trap for him, then throws him behind bars. But now Nancy, who had already been sharing visions of the same boogeyman in her dreams, becomes the killer’s next target. The majority of Nightmare‘s running time is devoted to Nancy trying to stay awake while trying to figure out exactly what “Fred Krueger” is. Her boyfriend isn’t much help, and her parents think she’s just hysterical at the violent loss of her best friend: but there’s a glimmer of recognition in her mother’s eye when she says her boogeyman’s name.

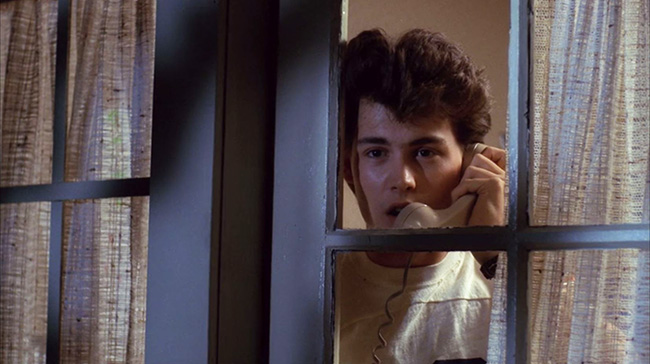

Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) stalks Nancy in her home. Wes Craven seldom gives us a clear look at Freddy outside of shadows.

Throughout, Craven maintains a sense of humor that never goes to the jokey excesses of some of its sequels. Craven was 45 when he made A Nightmare on Elm Street, whose cast members are playing characters that are 15 or 16 years old. After a sleepless night, Nancy looks in the mirror and laments, “Oh God, I look twenty years old!” (In fact, Langenkamp was 20 when this film was released, though she credibly plays someone younger.) Unlike most slasher films where it feels like the screenwriter is asleep at the typewriter, all the dialogue snaps. “Guys can have nightmares too, you know,” Rod grouses. “[Girls] ain’t got a corner on the market or somethin’.” After one character’s death, depicted as a geyser of blood shooting from the bed to the ceiling, one cop comments to the other that instead of a stretcher they might need a mop. Late in the film, Nancy’s perpetually drunk or drugged mother (Ronee Blakley, Nashville) reveals that she – and many of the other adults around Elm Street – formed a mob and burned child-killer Fred Krueger to death: “He’s dead, honey, because Mommy killed him,” she says sweetly. Craven always liked to run down a checklist of things that creep people out, and squeeze as much of them as possible into his movies. In Nightmare his list includes maggots (which seep out of Krueger’s wounds), millipedes, dark bedrooms in the middle of the night, and, of course, high school hall monitors. Freddy disguises himself as one when Nancy falls asleep in class. When she wakes up screaming and flees the classroom, her teacher reminds her, “You’ll need a hall pass!” But even this doesn’t play like a gag. Very much like John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), Craven’s suburbia is always believable. Still, it’s very funny when, after Nancy’s mother leaves the room in the middle of the night, we see Nancy pull out a Mr. Coffee from out of hiding, a fresh pot already brewed.

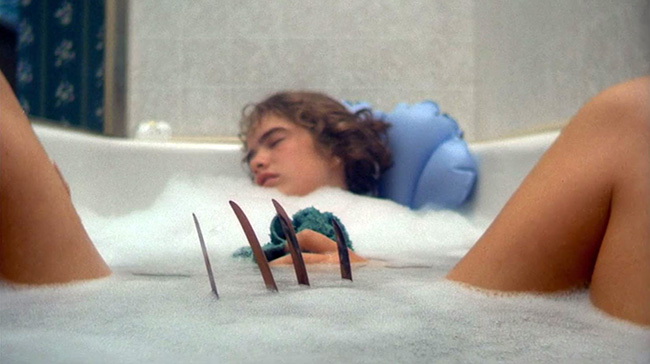

Nancy falls asleep in the bath.

A Nightmare on Elm Street still speaks to teenagers, even as it’s gently poking fun at them. Because if you are Nancy’s age and you’re shuddering through this movie, you understand that parents won’t get the gravity of what’s happening to Nancy. You even understand the betrayal when you learn that, yes, this is the adults’ fault after all – of course Mom keeps the killer’s glove in the basement furnace; of course she knows the boogeyman’s name; of course she helped start all this. Like a young adult novel, it speaks to teenage paranoia and the growing awareness of being, ultimately, on your own (and, in fact, Freddy has spawned young adult novels). The ending is downbeat, underlining that you can’t escape the nightmare – it just continues on, dreams within dreams, until you’re killed. Actually, I disliked the ending when I first saw the film. But on a rewatch it feels perfect: there should be no escape, no waking up. Not to mention that Craven’s sly sense of humor is still intact. Nancy’s addict mother is now dressed in white, emerging onto the porch to the sound of chirping birds: “I feel like a million bucks! You say you’ve bottomed out when you can’t remember the night before. No, baby, I’m going to stop drinking. I just don’t feel like it anymore.” It’s the first clue that maybe this isn’t real – followed by confirmation a second later when all of Nancy’s dead friends pull up at the curb. Surely my anger when I was younger is because I was in Nancy’s shoes, I wanted her to escape. But as an adult I can hear Craven cackling behind the camera as the kids drive away in a convertible with a red-and-green-striped top. Forget everything that followed this film, even though some of it was worthy. A Nightmare on Elm Street is perfect as its own self-contained, endlessly looping nightmare, a testament to the late Craven’s smarts and craft.