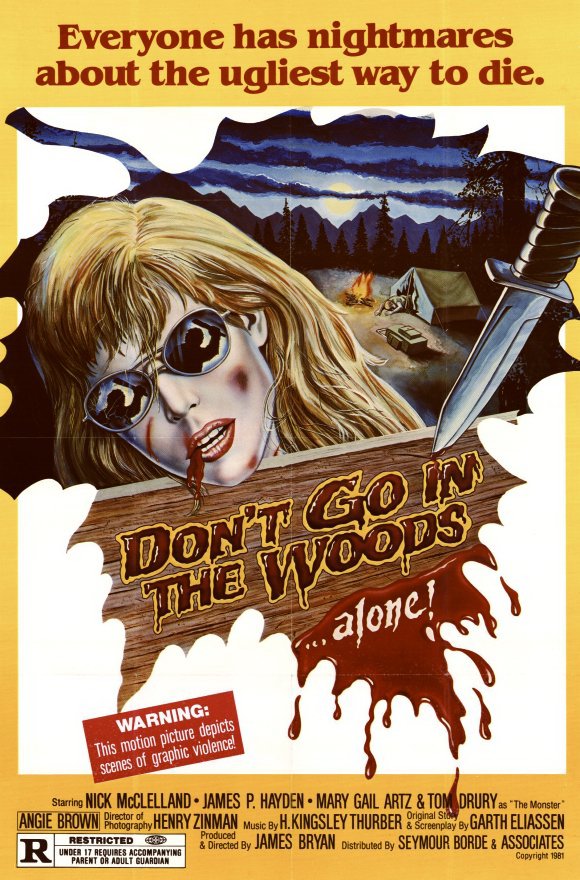

Don’t Go in the Woods (1981) had the benefit of arriving at the height of the slasher movie boom, reaching theaters after Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980) and in the same year as The Burning (1981). A nonstop stream of slasher films following roughly the same formula – young people, gory murders, sex, the “final girl,” and so on – were a staple of theaters and drive-ins. Critics were disgusted at them, teenagers flocked to them. But Don’t Go in the Woods had something special going for it, something to separate it from the pack: complete and utter incompetence. Director James Bryan largely specialized in porn, though he was transitioning into different kinds of exploitation, including biker movie (Hell Riders with Adam West and Tina Louise, 1984), action (The Executioner, Part II, 1984), and comedy (Boogievision, 1977). Don’t Go in the Woods is his attempt at horror, and perhaps it’s for the best that he quickly left the genre behind him. At times it feels like a computer program was fed different slasher movie elements, choked on its punch-cards, and spat out a randomly composed, whimsically written, incoherently edited, fake-blood-spattered mess. At least you can say it has everything. Well, except for the sex. Or suspense.

A birdwatcher becomes the first of the victims. I don’t know his name, and neither do you.

Bryan and his crew shot in the mountains of Utah, providing a very cheap but worthwhile special effect: beautiful locations. On Vinegar Syndrome’s Blu-Ray, restored directly from the original interpositive, the green foliage is practically fluorescent. The mountain peaks are shrouded in mist. The sky above the canopy of trees is blue, the bubbling mountain streams sparkle. Then come the buckets of red blood, dousing the amateur actors. The body count begins piling up before you even know who the main characters are. But – in retrospect – they are four young campers: the know-it-all guide, Craig (James P. Hayden); whiny Peter (Nick McClelland), redhead Ingrid (Mary Gail Artz), and brunette Joanne (Angie Brown). Craig looks a bit like Micky Dolenz, wears a cowboy hat, and never stops giving advice on how to find your way through the woods. Peter wears a tee-shirt advertising Bryan’s movie Boogievision, because every little bit helps. The actors, like most everyone in the film, speak in looped dialogue. It is difficult to tell exactly what they’re talking about, but generally everyone seems to hate each other. With disorienting frequency we cut away to other people wandering in the woods, who are quickly murdered. A birdwatcher. A young mother painting on a canvas while her baby watches from her jumper. A married pair of middle-aged tourists. From time to time we see a fat man in a wheelchair, alone in the wilderness, struggling to get up a hill. The soundtrack makes goofy wonk-wonk noises. We wait for him to get killed. But he’s usually just trying to make do without any apparent talent guiding that wheelchair. After a while, we begin to ask questions extending beyond the usual “Who is this person?” that we’ve been asking of most everyone in the film so far. We start to wonder: How did he get into the middle of the woods by himself? Why is he alone? Why doesn’t he know how to use a wheelchair? If he doesn’t know how to use a wheelchair, how did he get this far into the mountains alone and unaided? And – no, seriously – who is he, exactly?

Just another victim. Where did she come from? Where was she going? Did she hope to sell her painting, or was this more of a hobby?

A sheriff (Ken Carter, but he really ought to be Alan Hale Jr.) drives up into the mountains with his deputy (David Barth) to investigate. It’s typical of the film’s surreal editing that at one point a line of dialogue between them drops abruptly in the middle of a sentence, then the other one answers as though nothing has happened. The film was edited by dull scissors. One of the few scenes shot at night is unintentionally Buñuelian: Craig tells his fellow campers a scary story around a campfire, but the camera never moves from its poorly-lit vantage, and we never see Craig’s face. Is Craig even there? Probably not. Perhaps James Bryan is trying to tell us that we’re all really alone, and isolated in the frame, never given the solace of an edit to another angle, and always poorly lit. I know I feel that way sometimes. But enough of these types of scenes and you begin to feel a little queasy. We’re supposed to, right? The bad editing and amateurish, oft-mumbled acting is all to build a feeling of discomfort and dread? Eventually the killer is seen: a crazed mountain man with weird beads strung over his face. He lives in a cabin-in-the-woods whose main point of interest is a creepy doll. When Peter stumbles out of the woods and into a hospital, he leaves shortly thereafter to rescue his friends. “That guy Peter flew the coop?” the sheriff asks. “We’ve got a mental case too?” says the exasperated deputy. They follow him, exhausted, back up the mountain. The man in the wheelchair is killed. Oddly, this now feels like narrative progression. The baby in the jumper is being raised by the mountain man, and she’s playing with a hatchet. This movie has a baby playing with a hatchet. Someone please take that hatchet away from that baby. I know this is Utah – I used to live there, I get it – but come on. Then Peter and Ingrid finally get the upper hand on the killer, and stab him over and over with spears, pinning him to the ground, stabbing, stabbing, stabbing, stabbing. He’s been dead a while. They keep stabbing.

So. Don’t go in the woods?