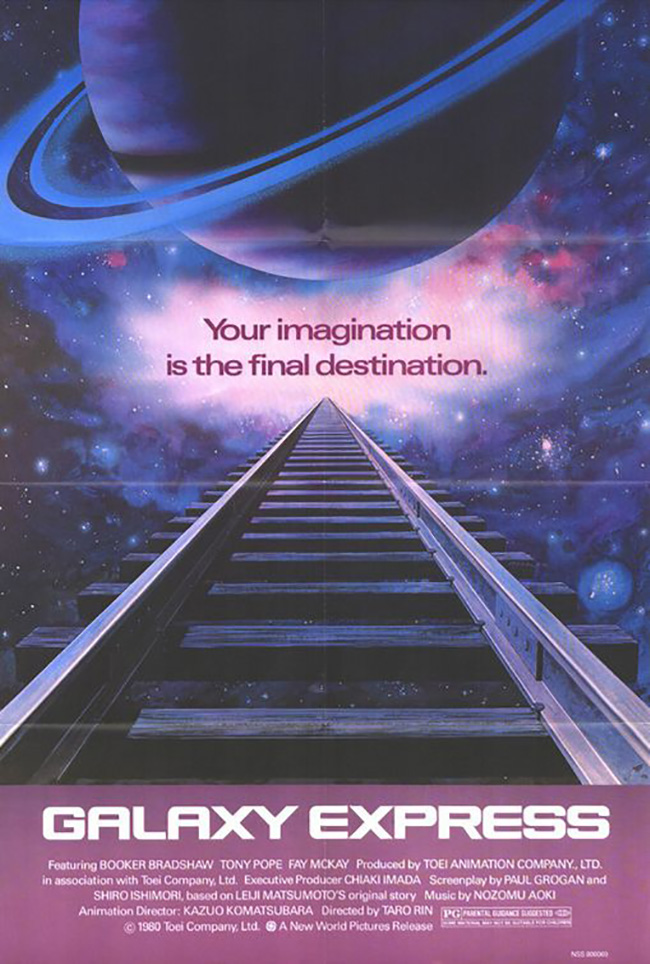

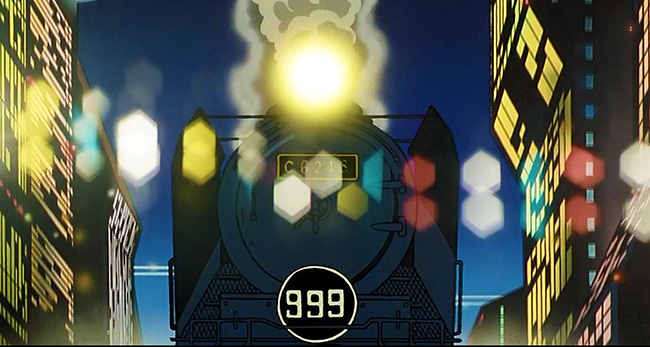

At one point in Sans Soleil (1983), essay filmmaker Chris Marker, visiting Japan, turns his camera on his hotel television set. He watches footage of Japanese recovering from an earthquake, he watches samurai movies, and he watches the anime TV series Galaxy Express 999 (1978-1981), as a steam locomotive rockets up a skyward-pointing track and then straight into the black cosmos. Marker says, “Last night’s quake helped me solve the problem. Poetry is born of insecurity…By living on a rug that jesting nature is ever ready to pull out from under them, they’ve gotten into the habit of moving about in a world of appearances, fragile, fleeting, revocable, of trains that fly from planet to planet, of samurais fighting in an immutable past. That’s called the impermanence of things.” Marker, a Frenchman, was watching TV without dubbing or subtitles, spending his days wandering in Tokyo crowds, lost, pondering the culture while trying to place an idea – what becomes Sans Soleil. If he’d deciphered Galaxy Express 999, he probably would have liked it; after all, he’d directed La Jetée (1962): a science fiction film, the greatest short film ever made, and the inspiration for Twelve Monkeys (1995). But by letting the images wash over him he grasped enough: a train leaving Earth and traveling from planet to planet. Homelessness. Insecurity. Impermanence. He’d actually settled on one of the central ideas of Galaxy Express. The show got its point across with the sight of an express train traveling through outer space, home far behind.

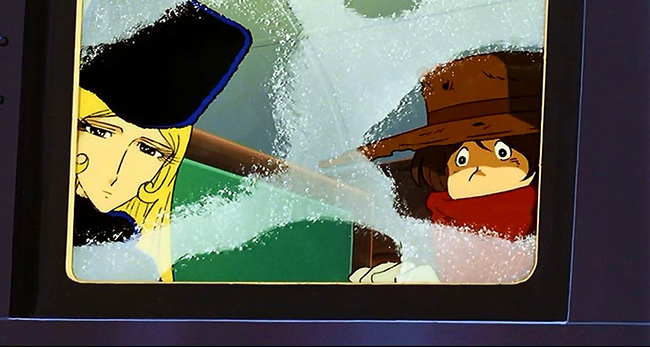

The temperature drops as the mysterious Maetel and the young Tetsuro travel to Pluto.

Galaxy Express originated as a serialized manga by Leiji Matsumoto, begun in 1977. The TV series commenced the following year, and the feature film Galaxy Express 999 (1979) had the unusual distinction of airing while the show was still in progress. Complicating the matter, the movie was a distillation of the series’ overarching plot, condensing (and revising) four years’ worth of episodes into two hours, and providing a premature conclusion. Writer and director Rintaro was making his feature filmmaking debut; he would later direct Harmagedon (1983), X (1996), and the terrific Metropolis (2001), among others. Like Battle of the Planets, Voltron, and Robotech, Galaxy Express has served as one of those entry-points to anime for American fans. I first watched Galaxy Express 999 on VHS tape, dubbed and pan-and-scan, but like Marker, I was captivated by its very visual ideas. The Galaxy Express departs Earth, travels through the solar system and beyond, ultimately to a world where “mechanized” bodies are offered, free of charge, to those seeking immortality. But tickets to board the train are available only to the very wealthy. Tetsuro, a child, longs to board the train: his mother was murdered by mechanized hunters serving the callous Count Mecha, who resides in Time Castle. In a flashback we see her shivering amidst falling snow and a green sky. “If we had mechanized bodies we’d hardly be able to feel the cold at all,” she tells her son. After she’s killed, he holds a snowball in his hand stained with her blood. Then he joins up with Maetel, a blonde woman in a black coat and fur hat, looking like she’s stepped out of Doctor Zhivago. He tells her he wants a free mechanized body – then he’ll never have to feel cold. He also wants to take revenge on Count Mecha. For mysterious reasons she’s willing to bring him aboard the Galaxy Express, and soon they’re headed toward their first stop, Saturn’s moon Titan.

On Pluto, Shadow tends to the “graves of ice.”

The set-up is actually perfect for a television series: with each episode, the Galaxy Express visits a new planet, or encounters something in-between. (Star Trek is the clear model, although this acts as a more surreal cousin.) As a feature film, Rintaro makes the best of it, offering a few key stopping-points, all of which contribute to the story and its ending. In Titan, an old woman gives Tetsuro a Cosmo Gun, as well as a ragged hat which has a symbolic significance revealed much later. On Pluto – the film’s most evocative setpiece – he encounters the “graves of ice” where bodies are kept preserved, their owners having abandoned them for mechanized ones. Maetel is seen gazing through the ice at one particular frozen body. On the planet Heavy Melder, Tetsuro confronts Count Mecha and has his vengeance, and at his final destination, in the Andromeda Galaxy, he comes to realize that having a mechanized body might not be the answer to his problems after all. He also learns the secret of Maetel, and a climactic battle features his new companions Emeraldas and Captain Harlock, pirates who would have their own spin-off films and adventures. All of it is animated with rich colors, vitality, and imagination. Saturn has about 62 moons, and judging by the background paintings used for Titan’s surface, the artists seem determined to fit them all in. Pluto’s an icy cemetery (Pluto is the god of the Underworld, after all), with thousands of prone bodies frozen in layers in the ice, and Shadow’s abode, where she keeps her original body, is an igloo-like mausoleum.

The pirate queen Emeraldas.

By keeping the planetary adventures on-point, everything builds toward Tetsuro’s epiphany, which is that exchanging your humanity for immortality is a bum deal. Maetel, we learn, has long since surrendered her original body, and is passing from one shell to another, like the Express passing its cosmic stations; she breaks out of her ennui to destroy the mechanized empire, but still she returns to the Galaxy Express, always traveling. Neither destruction nor revenge offer satisfaction: it’s interesting that the prop villain Count Mecha is killed by Tetsuro before the final act, leaving Tetsuro to move restlessly on, his existential problem unsolved. (Alas, this can also make the film feel a little longer than it is.) Chris Marker, watching the untranslated images on a TV set in a Japanese hotel room, still lights on the central melancholy at the heart of the film. Tetsuro is anxious to leave home, because his home was a site of tragedy. But moving restlessly onward leaves him forever without a home. Maetel becomes his surrogate mother, which is not my personal interpretation but a literal story-point: Maetel has taken his mother’s cloned body as the latest vessel in her immortal wandering. (The fact that Tetsuro doesn’t realize this from the start is somewhat understandable. Most of Leiji Matsumoto’s women are cast from the same mold.) Traveling toward the Andromeda Galaxy, he obtains a surrogate family of sorts with Emeraldas, Harlock, a bandit named Antares, and the glass-bodied Galaxy Express waitress Claire. But Antares stays behind on Titan, Claire sacrifices herself, and pirates never stay in one place. Even by the end of the film, when Tetsuro is finally home in Megalopolis, he’s chasing after the Galaxy Express – a take on the old familiar train station scene, where one lover chases while the other leans out the window until they’re permanently separated. Except, in this case, we know Maetel is Tetsuro’s mother (of sorts). Freudian implications aside, we’re watching as Tetsuro loses his mother a second time, and the train lifts off into space, abandoning him. A cheesy song plays on the soundtrack as the credits roll. Poetry is born of insecurity, and Galaxy Express 999 is anime pop-poetry at its finest.