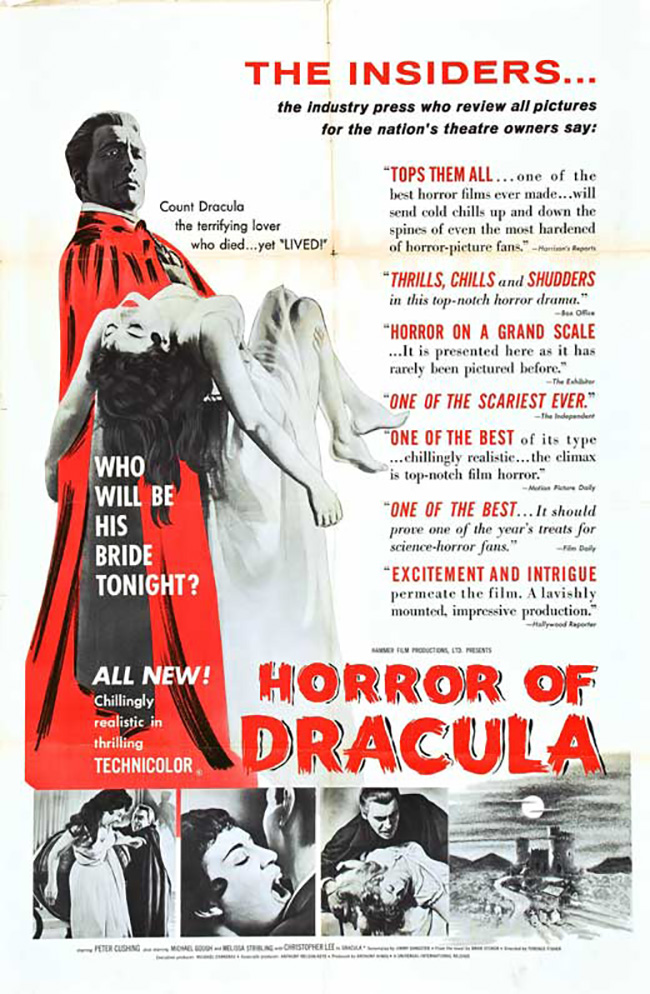

If there is one film which defines Hammer horror, it is Dracula (1958). It was the natural follow-up to the company’s successful, X-certified The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), which brought back Gothic horror with a vengeance – that is, with full-color gore and shocks, handsome production design to hide a modest budget, and impeccable performances. All the key players were brought back: stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, director Terence Fisher, composer James Bernard, cinematographer Jack Asher, and screenwriter Jimmy Sangster. But Hammer’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel wasn’t just some more-of-the-same cash-in; instead, it was a perfection of the studio’s approach to horror. Even more than Curse of Frankenstein, Dracula set the template for all that followed. It was released in the U.S. as Horror of Dracula, partly to reassure American audiences that it wasn’t just another reissue of the Bela Lugosi film, and partly because the title made it pair well with Curse of Frankenstein on a double bill. (A famous poster declares, “Frankenstein Spills It! Dracula Drinks It!”) But the film quickly separates itself from the Universal monster-mashes of the 30’s, even though Universal distributed the film in the U.S. as part of a deal to grant Hammer rights to the Dracula character. Christopher Lee’s Count was younger and sexier than Lugosi. Terence Fisher’s direction was considerably more dynamic than Tod Browning’s. And Peter Cushing was a sympathetic and athletic Van Helsing, in contrast to the professorial Edward Van Sloan.

Peter Cushing as Van Helsing.

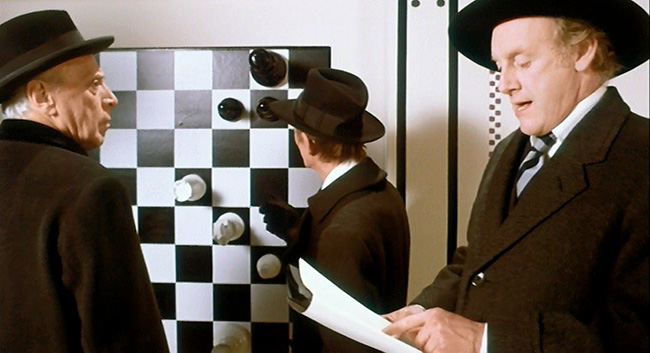

Both a Dracula and a Frankenstein series followed in the wake of the two films’ success, each running well into the 70’s. Peter Cushing fronted the Frankenstein films (with one exception), and Christopher Lee the Draculas (with at least one exception*). It’s interesting that Lee came to be most associated with the Dracula franchise, considering that he’s hardly in this first film. As with Stoker’s novel, the Count makes carefully rationed appearances, and thus doubles his impact when he does appear, blood on his mouth and eyes bloodshot. Lee only has the first act of the film to present the more civilized side of Dracula, offering the use of his library to the visiting Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen, Quatermass 2), and presenting his guest handsomely furnished quarters that include a stained glass window, a chess set, and a fireplace. Later he will provide the film’s sex appeal, kissing Mina Holmwood (Melissa Stribling, The League of Gentlemen) up and down her sensual features before biting her neck. But Peter Cushing is really the star of the movie, and although this is the one that made Lee famous, it’s appropriate that Cushing’s name is above the title on most posters. Sangster’s script condenses Stoker’s plot and abandons or combines some of his characters, but his most inspired move was to make Van Helsing the film’s protagonist. Van Helsing was always an important catalyst in the plot, but never as centralized. Sangster even kills off Jonathan Harker at the end of the first act, which means that Harker’s only function in this version of the story is to introduce Dracula, his castle, and the idea of a vampire slave (Valerie Gaunt, The Curse of Frankenstein), as well as to leave a diary which will ultimately convince the skeptical Arthur Holmwood (Michael Gough, Horrors of the Black Museum) that vampires are real. Meanwhile, Cushing is the audience surrogate: the one who knows the threat Dracula poses, who asks the right questions and brings the right equipment. He also gives the film some heart. When young Tania (Janine Faye) is trembling in a cemetery after an encounter with a vampire incarnation of her Aunt Lucy (Carol Marsh), Van Helsing takes a pause from his hunting to kneel before her, gingerly give her his coat and crucifix, and distract her with a line that reveals his inner optimism: “If you look over there, you can see the sun come up.”

Van Helsing comforts Tania (Janine Faye) in a graveyard stalked by a vampire.

There’s also quite a bit of Terence Fisher in that line – Fisher excelled at presenting the battle between Satanic evil and a Christian good, as in The Devil Rides Out (1968), because he really believed in it. His Dracula films, such as his excellent follow-up Brides of Dracula (1960), are propelled by that conviction. Nonetheless, there’s a lot of macabre humor lurking throughout Dracula. When Lucy is holding Tania’s hand in the graveyard, her promise of “I know somewhere nice and quiet where we can play” is both menacing and a bit of a sick joke. There’s more than a hint of incestuousness to Lucy’s smile when her brother Arthur visits her crypt: “Dear brother, why didn’t you come sooner? Come, let me kiss you.” Even when we first see Lucy preparing for Dracula’s midnight visit, it’s easy to smile at how overt is the film’s “subtext.” She readies the room for her favored lover, and arranges herself seductively on the bed, all set to be ravished. A joking undertaker (Miles Malleson) offers a strong dose of gallows humor – to an awkward Van Helsing and appalled Arthur – and there’s even some (unsuccessful) slapstick late in the film, but Dracula is at its best when it’s delighting like a libertine at the fresh explorations of the novel’s blood and sex. Sure, women swooned at Lugosi’s Count too, and Dracula’s Daughter (1936) played with the theme of lesbianism, but Dracula feels like a kid discovering a new playground – even if it comes in the shape of a decrepit graveyard. What would become stale in vampire films of later decades was fresh in 1958, and still feels fresh on each revisit, thanks to Hammer’s commitment to the material.

Publicity still showing the disintegration of Dracula (Christopher Lee).

In 2011 Simon Rowson, a Hammer fan living in Japan, was able to uncover a Japanese print of the film which contained footage censored from all other prints, including a slightly extended version of Mina’s seduction, and, most remarkably, a longer death scene for Dracula, with unique makeup effects including the Count peeling off his own face. Hammer had previously restored the film in 2007, and proceeded to acquire and incorporate the uncovered footage into a new 2012 restoration. Both versions are available on the 2013 Blu-Ray/DVD set, for now only available in Region 2. The Blu-Ray has proven controversial, with many vocal fans deriding the restoration’s slightly darker and bluer palette. Even tainted by all that discussion, in (finally) viewing the Blu-Ray I find the change less objectionable. (I’m inclined to believe those experts who state this grading is not what the film originally looked like. Personally, I wasn’t alive when the film was released theatrically, and I’ve only ever watched the film on home video or cable TV.) All things considered, the Blu-Ray is still a significant visual upgrade from the old Warner DVD, and it’s a lot of fun to watch it with the reintroduction of the censored footage. Accompanied by multiple documentaries, the 2007 BFI restoration, and even the unrestored Japanese reels, this is currently the best and most thorough presentation of Hammer’s Dracula available. It remains to be seen if an American release will be forthcoming, and if so, whether the presentation will be superior, inferior, or just a port of the same disc. Warner previously released Horror of Dracula as part of a Hammer box set (and two subsequent Hammer-themed DVD compilations); some of those films will be released in October on a Blu-Ray set, but not Dracula. With the recent passing of Christopher Lee, one would imagine that demand has never been higher for the definitive release of his most famous film. If the British Blu-Ray isn’t 100% perfect, at least it’s very close.

*Brides of Dracula (1960) featured Cushing but not Lee (nor a Dracula). The other possible exception is The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974) if you consider it part of the series. As for the Frankenstein films, Cushing did not appear in The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), which featured a younger Baron played by Ralph Bates.