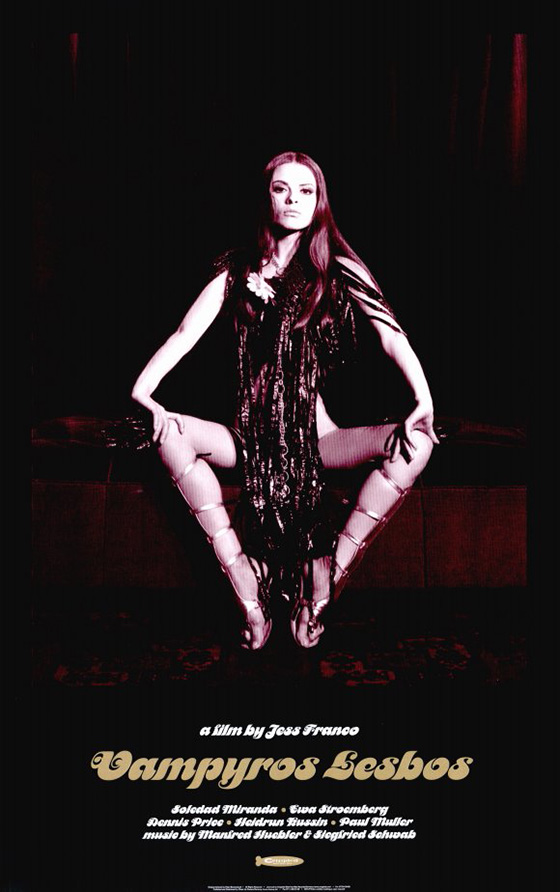

What makes Vampyros Lesbos (1970) such a satisfying effort in the endless and often frustrating filmography of Jess Franco is that, for all the director’s trademark random zooms, out of focus shots, silly dialogue, and numbing repetition, here it all works in synch like one of Kenneth Anger’s celluloid incantations to the Devil. Vampyros Lesbos is not just another piece of sexploitation, through which Franco often sleepwalked. It is a vividly realized rock ‘n’ roll poem, not so much telling a story as riffing on the theme of lesbian vampirism – an excuse for a psychedelic, erotic, hypnotic dream for the span of 80 minutes. At the center of it all is Soledad Miranda, Franco’s muse of the moment. The two had briefly crossed paths with his La reina del Tabarín (1960), and after she had worked for various Spanish directors in the 60’s, the pair reunited for a series of horror films and thrillers in stark contrast to the mainstream, often musical work that had become her forté. With Franco she would make Count Dracula (1970), Nightmares Come at Night (1970), Sex Charade (1970), Eugénie de Sade (1970), She Killed in Ecstasy (1970), The Devil Came from Akaseva (1970), and this film, all breathlessly shot back-to-back before the tragic car accident that took her life. Franco, along with producer Artur Brauner, hoped that Miranda would be the next big thing, and thought of these exploitation films as vehicles to spotlight her beauty and talent. But Miranda, already a prolific actress and singer, was entering the next phase of her acting career, and was looking to break free of the regional, censorship-heavy Spanish market. She shed her clothes and her former wholesome persona, and submitted herself to the wild, strange world of Jess Franco. Vampyros Lesbos is bursting at the seams with delirious energy and intensity, as though Miranda and Franco were willing this humble B-movie – with its almost crude simplicity, vague gestures at vampire lore, and trippy soundtrack – into something of occult importance.

Linda (Ewa Strömberg) looms over her vampire mentor, Countess Carody (Soledad Miranda).

Miranda plays the Countess Nadine Carody, a Turkish vampire once bitten by Dracula himself. Franco flips the genre expectations, deliberately separating his film from Hammer-isms: Miranda’s vampiress loves to sunbathe, and when she’s performing a striptease at a hip nightclub, her performance is in front of a mirror (she casts a reflection). It’s one of these performances that captures the attention of Linda Westinghouse (Ewa Strömberg, She Killed in Ecstasy), who abandons her confounded boyfriend Omar (Andrea Montchal, Eugénie de Sade) for a trip to Nadine’s private island off the shore of Istanbul. Nadine treats Linda to a swim, a bit of wine, some sex, and a gory bite on the neck. Linda’s growing obsession with Nadine, and her nascent vampirism, draws the attention of Dr. Seward (Dennis Price, Twins of Evil) and his Renfield-like female patient, Agra (Heidrun Kussin), who is already mad with desire for the Countess. But just as Vampyros Lesbos reveals itself to be a gender-swapped version of Dracula, Franco adds a few subversive twists. Dr. Seward is interested in vampires only because he wishes to become one himself. His overture to Nadine is rejected, just as Linda rejects Omar – the two women are destined for one another. Ultimately, Linda is not rescued by a man: she destroys her master on her own through voracious hunger, biting through Nadine’s neck. Even as Linda narrates the close of the film, as though order has been restored, she reassures us that she will never forget the beautiful dream of living under Nadine’s spell.

Countess Nadine Carody.

A simple plot description doesn’t capture the groovy and woozy qualities of this stream-of-consciousness vampire movie. One digression features Franco himself, playing a sadistic killer called Memmet, and though his story doesn’t seem to fit logically into the larger one, it only adds to the film’s stream-of-consciousness, dreamlike style. Memorably, Miranda’s costume is a robe of black lace, a red scarf wrapped around her neck and dropping vertically to her feet. Her straight black hair frames wide lips and large, dark eyes: she embodies a being of insatiable hunger. Apart from Miranda, the film’s most notable feature is the music by the team of keyboardist Manfred Hübler and guitarist Siegfried Schwab. Together they craft a dazzling soundtrack of lysergic lounge music, barking distorted gibberish like air traffic controllers from another dimension, swooning, moaning, sizzling grooves. Their music elevates Soledad Miranda to the status of vampire goddess: her eyes become that much bigger, her red scarf that much longer. Franco takes inspiration, and films a scorpion drowning in a pool, blood dripping down a glass door, a skyline of cupolas in Istanbul, and Soledad, Soledad, Soledad, lying on her back with her face half-veiled by her scarf and black hair, her fingers extended toward the camera, beckoning. Which is to say that this Franco film becomes something else: a paean to the black magic of female sexuality. Although this film was released during a wave of sexy vampire movies, it can easily be distinguished from both The Vampire Lovers (1970) – Hammer tentatively exploring sexploitation – and the Jean Rollin sequence of lyrical vampire films, which are quieter and considerably more French. Severin’s new Blu-Ray, from a German print of this German production, is lushly rendered; the film has never looked better (ignore my screenshots, from other sources). Contrast this with the bonus disc, a ragged and washed-out edition of the alternate Spanish cut of the film for completists. Severin has also released She Killed in Ecstasy on Blu-Ray, with a bonus soundtrack CD (3 Films by Jess Franco) featuring the music of Manfred Hübler and Siegfried Schwab, and which Quentin Tarantino helped popularize in the mid-90’s thanks to the Jackie Brown soundtrack. Both films are essential slices of Eurocult.