The Astrologer (1975) comes to us from the mind (and Id) of the late Craig Denney, the film’s director and star, who looks like a cross between Matt Damon and Matt Berry – the British comedian and musician who appeared in The IT Crowd, Snuff Box, and Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace. For a brief moment in the middle of The Astrologer, as I was beginning to lose all sense of reality, I began to wonder if this “film” was, somehow, all an elaborate con of Berry’s, and that this would turn out to be another installment of the faux-retro Darkplace. But no – there is something sweaty, sunburned, coke-addled, and altogether far too authentic in every jarring editing choice, every loving shot of Denney’s untoned, shirtless body, and the film’s unique, personal point-of-view. This is an indelible portrait of the duplicity of women, the corruption of fame, the dangers of jewel-smuggling, and, most of all, the importance of astrology, as filtered through Denney’s peculiar imagination. It is semi-autobiographical, supposedly. Like Tommy Wiseau and The Room (2003), Denney had the money and the means to film his own personal vision – just not the talent to execute nor the clarity to see what he was actually creating. It is no exaggeration to say that The Astrologer is The Room of 1975, even if this doesn’t precisely capture just how weird the movie is. And original. But the world wasn’t quite ready for The Astrologer, which played briefly in Australia, then resurfaced on the CBS Late Movie in June of 1980 before vanishing entirely.

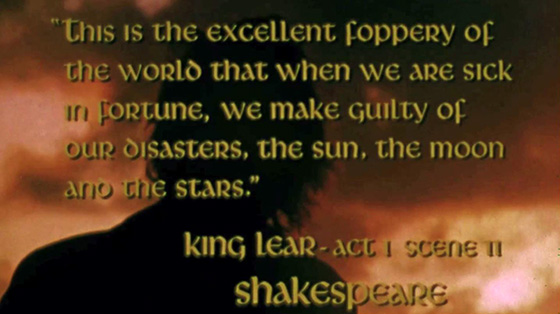

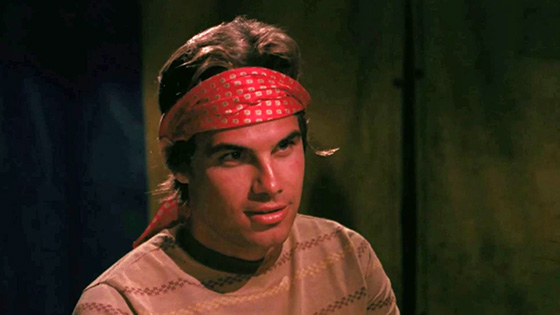

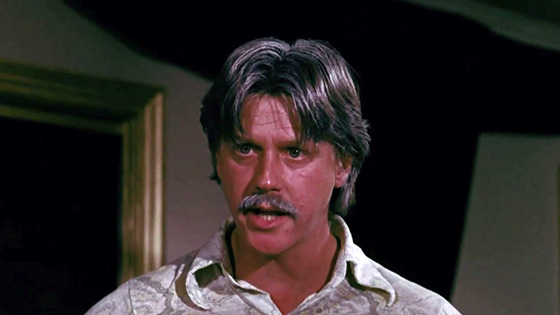

Director Craig Denney as Alexander, the Astrologer.

I learn these facts from actor and Astrologer fan Pat Healy (The Innkeepers, Cheap Thrills), who introduced the screening at the 2015 Wisconsin Film Festival. The obscurity has recently received a 2K digital restoration from the American Genre Film Archive, and played last year’s Fantastic Fest in Austin, where Healy first viewed it. He describes The Astrologer as “Indiana Jones meets The Jerk meets some schizophrenic guy on crack telling you his life story.” Denney plays Alexander, a self-described mystic at a carnival attraction (his trailer with “Alexander” painted on the side of it) whose talents largely derive from picking the pockets of his marks. His elaborate astrologer garb includes a red scarf on his head, a tan tee-shirt, and blue jeans. He falls for one of his marks, Darrien (Darrien Earle), and insists on refunding her money because he wants to marry her. She acquiesces quickly. “I think I’m going to enjoy this,” she enthuses. “I’ve never lived in a trailer before, but…” Soon they’re hobnobbing with an oil baron and his wife, Boyd and Rita, in a sequence that consists entirely of close-ups of hands and overdubbed voices. Abruptly, we are in Kenya. Alexander has been arrested for diamond smuggling on behalf of his oil baron patron. At the end of a line of shirtless, strapping African prisoners is the short, schlubby, and equally shirtless Alexander, his thumbs proudly hooked behind his belt buckle. A note: Denney is always smiling in this film. It is a wise, knowing, contented smile. The film, says the smile, is going according to plan. It is a serene smile.

In this case, Alexander is smiling because he knows his wealthy patron will get him sprung – and sprung he soon is. He travels with Boyd and Rita deep into the jungle to find a legendary ruby. Boyd is bitten by a deadly cobra and…let me explain the jungle. The jungle is mostly a wall covered in ivy. During this African sequence, one often gets the impression that the actors are walking through the shrubbery just off the path at a local zoo. When Alexander is later traveling with a widowed Rita, he points out quicksand, but we don’t see it at first. The camera is afraid to look. But soon Rita is swallowed by it, and we get a gratifying image of her hand disappearing into quicksand (albeit free of continuity, like the rest of the movie). The scenery at last opens up when Alexander takes a schooner out to sea, which becomes a music video for The Moody Blues’ “Tuesday Afternoon.” Superimposed over shots of Alexander gazing out at the sunlit waters are a few months’ worth of calendar dates flying at the viewer. The rights weren’t cleared with the record label, but nonetheless the ending credits proclaim, “Music by The Moody Blues.” We’ll also hear Elvis Presley’s “It’s Only Make Believe” and Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” among others, but no one crafts a musical montage like Craig Denney. Tommy Edwards’ romantic “It’s All in the Game” accompanies a tour of a men’s urinal shot through a fish-eye lens, juxtaposing the erotic art on the walls with middle-aged prostitutes flashing the camera. Meanwhile, Alexander has murdered one man in Africa, witnesses another murder in Tahiti, and returns to the United States rich with jewel-smuggling cash. His astrologer’s skills become so renowned that soon the U.S. Navy is knocking on his door, and someone known only as “The Admiral” enlists Alexander’s skills to keep ships from sinking in the Bermuda Triangle. Alexander’s explanation for the shipwrecks consists of lots of stock footage of submarines while he describes complex astrological arrangements, most of them involving Uranus.

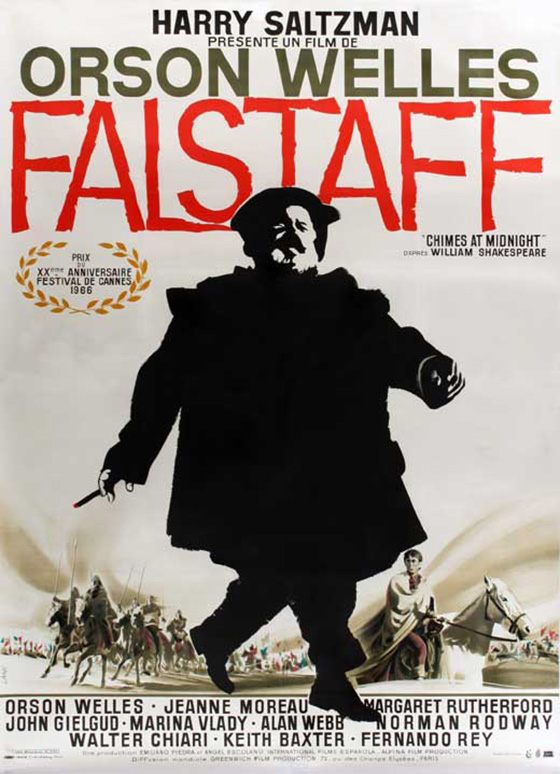

Arthyr Chadbourne as Alexander’s confidante, Arthyr.

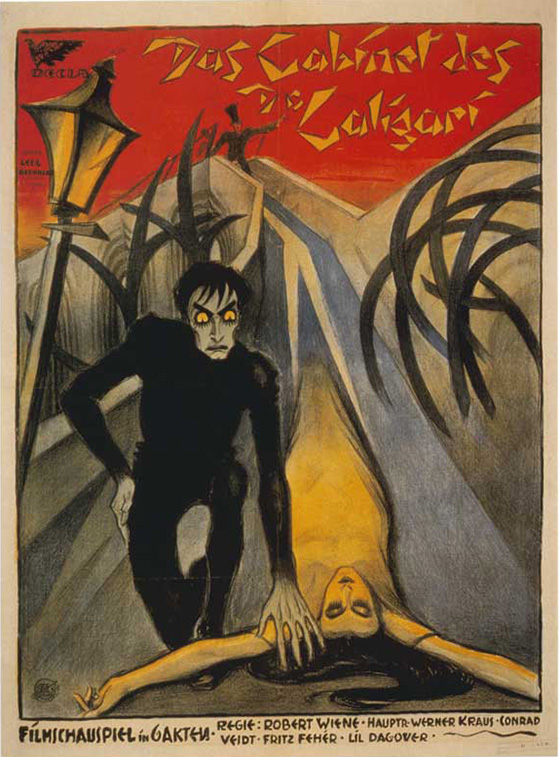

This last section of the film takes us through Alexander’s meteoric rise to fame as America’s preeminent astrologer, where his every move makes headlines. He creates a film called The Astrologer and attends the premiere, smiling at the screen, smiling at his performance (making love to a beautiful topless woman), smiling like he knows something we don’t. He rescues Darrien, who has descended into prostitution and is found sprawled on a bed with a rat on the windowsill, a mountain of crushed beer cans on the floor, and a bedside mirror with the following written neatly in lipstick: “God is dead,” “Hell on Earth,” “Shit on life.” His reunion with Darrien is short-lived, and their marriage is terminated following a slow-motion argument at a restaurant. A spinning newspaper announces that the Astrologer has signed for divorce. But this doesn’t stop him from strangling his wife in her lover’s bed, after shooting said lover through the window. The Admiral bails him out, for Alexander’s work is important. But Alexander has become a monster. After excoriating and then firing an actress, he chortles to his best friend Arthyr (Arthyr Chadbourne), “Now that’s how you treat actresses. They’re like hamburger meat. You buy them by the pound.” As his career begins to crumble, even Arthyr turns on him: “You’re not an astrologer. You’re an asshole!” This occurs during a rant in which the faces of those Alexander has wronged pass before him – including Arthyr’s face, even though Arthyr is sitting right there. The final image of the film is a quote from Shakespeare’s King Lear, of course: