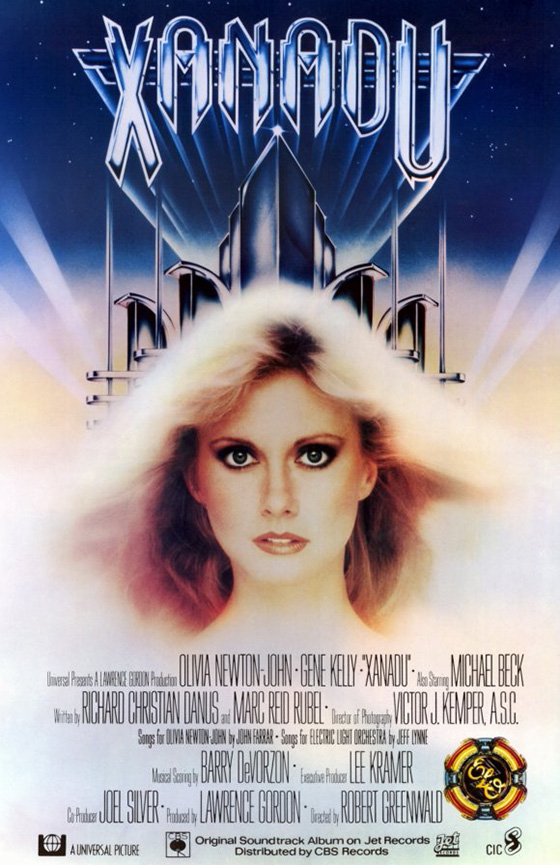

The term “guilty pleasure” seems to have been invented for Xanadu (1980). This is not a film one admits to liking in public. Still, it has become popular enough to have spawned a Broadway musical that was nominated for multiple Tonys. Because my sister was obsessed with the film as a child, so was I (I had no choice; she usually chose what we watched, which is why I, like many children, was traumatized by Little House on the Prairie, one of the most disturbing TV shows of all time). We watched Xanadu a lot. When I texted her this morning stating that I had just watched Xanadu, she replied, “Oh wow…that is so terrible, but I loved it so much. I don’t even know if I understood it. But the skating and the singing…” And because I was four years younger than her, the film was even more abstract, confused. I didn’t understand it. But the skating! The singing! Last night I decided to introduce my wife to the wonders of Xanadu. Afterward she asked, “So, when do I get that song out of my head?” “Never,” I told her honestly. “Whenever someone mentions Xanadu, that song will get stuck. That’s the deal.” So perhaps Xanadu is more like a curse that one passes to another, and the only way to get rid of Xanadu is to show it to someone else. (This is the plot of It Follows, right?)

The Greek Muses (including future Conan the Barbarian co-star Sandahl Bergman) emerge from a mural to ELO’s “I’m Alive.”

But there’s no denying that there is a pleasure to be taken out of the “guilty pleasure.” Someone had the good sense to hire Jeff Lynne and his Electric Light Orchestra to beef up the songbook alongside Olivia Newton-John’s longtime collaborator John Farrar. It’s Lynne who wrote the title song, which is essentially Newton-John fronting ELO (a combination that works). ELO also provides the songs “I’m Alive,” “All Over the World,” “The Fall,” and “Don’t Walk Away,” sounding very much their Mr. Blue Sky selves. Although I could stand to lose “Suspended in Time” and the big band pastiche “Whenever You’re Away from Me,” Farrar’s “Suddenly” is a flat-out lovely song, cynics; if nothing else, it’s an example of late 70’s/early 80’s easy listening at its least offensive. Obviously, your mileage will vary when it comes to musical tastes. But here’s the thing: even if you are enjoying the film solely as a “so bad it’s good” experience, Xanadu satisfies. This is a film that might have been just another Roller Boogie (1979), but somehow evolved into an Olivia Newton-John rock musical which takes pains to present disco and rock ‘n’ roll as a tribute to the Golden Age of Hollywood musicals, but within the confines of a roller rink. Not only was Gene Kelly convinced this was all a good idea, but he was talked into leading a roller derby brigade stomping their feet, crossing their arms into an X, and chanting “Xanadu!” He must have thought this was to be another charming retro-minded musical, like his cameo in the classic French film The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967). Xanadu is no Young Girls of Rochefort. But it is very much Xanadu, and that’s all that really matters.

Danny McGuire (Gene Kelly) dances with Kira (Olivia Newton-John) to “Whenever You’re Away from Me.”

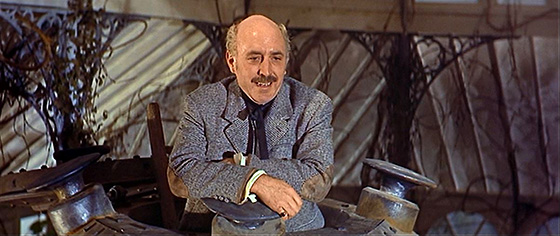

Kelly is playing Danny McGuire, an aging clarinetist who once led a Glen Miller-style big band. “Danny McGuire” was also the name of Kelly’s character in the 1944 film Cover Girl, which is appropriate, since Newton-John’s character in this film, Kira, graces an album cover herself. The album is by a band called The Nine Sisters, a reference to the Muses of Greek mythology, of which Kira is one – her real name being Terpsichore, the Muse of dance and song. McGuire knew one of Kira’s former incarnations, a singer from 1945, and in a daydream he imagines them dancing together. Kelly proves he can still cut up the dance floor, and Newton-John holds her own. This is the only scene in the movie which successfully pays tribute to Hollywood’s Golden Age without smearing it with neon mascara and glittery lip gloss, or lacing roller skates to its feet. Kelly can roller skate, but as his cinematic swan song, Xanadu is a peculiar choice, to put it mildly. It’s more than a cameo, more than the day’s shooting he put in for Jacques Demy and Rochefort, yet it’s amusing that he’s second billed while the film’s true leading man, Michael Beck (The Warriors), comes in a distant third: in a much smaller font after the opening title. Xanadu is a romance between Beck’s mural artist Sonny and Newton-John’s Kira, and his diminished status in the credits is just one sign of the film’s confused execution. Poor Danny McGuire is finally seeing the love of his life again, and she hasn’t aged; nevertheless, he shrugs and lets her run off with Sonny. How are we supposed to feel about that? Xanadu doesn’t have much time to dwell on it between musical numbers, which is fine, because all the dialogue in the film is disposable, if not outright painful, and the sooner it’s over the better. The story is a loose remake of 1947’s Down to Earth, and in an explicit visualization of the film’s Old Hollywood fetish, a big band led by a facsimile of the Andrews Sisters performs “Dancin'” on a stage directly opposite 80’s rock band The Tubes, grinding away at their own separate performance. Eventually the two stages begin to merge, the performers intermingle, and the songs become one. If you close your eyes, the effect works; but if you leave them open, my God. And that’s Xanadu in a nutshell. This is a film that got dressed in the dark.

Don Bluth’s animated sequence for “Don’t Walk Away.”

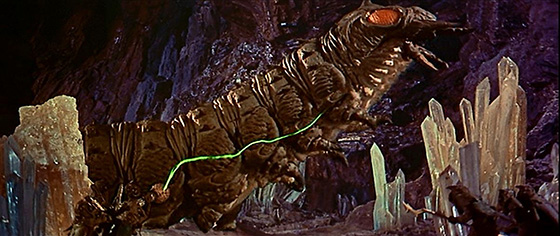

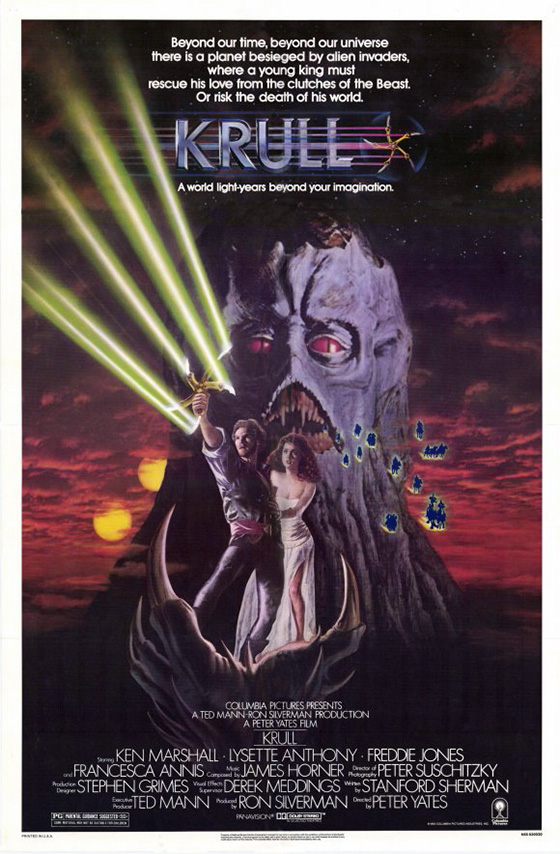

Sonny has fallen in love with the Muse of his dreams, though her true purpose is to inspire him to resurrect an abandoned auditorium to become the “Xanadu”: a roller skating disco nightclub fronted by Gene Kelly (just as Samuel Taylor Coleridge described it in 1797). Their love affair blossoms as it ought to: through musical numbers, first in “Suddenly” (roller skating around moving props) and then, with ELO’s “Don’t Walk Away,” in cel-animated form courtesy Don Bluth, who had recently led a mutiny of animators from Walt Disney Studios and was on his way to The Secret of NIMH (1982). Bluth’s vision of Kira is like a synthesis of Newton-John and the princess from his later laserdisc game Dragon’s Lair (1983). I doubt many would argue when I say this brief sequence is easily the best thing about Xanadu. Bluth uses his animation like a demo reel – showing off because he has to; he was forging a career as an independent animator to rival the monolithic Disney. It’s a staggering come-down when we cross from “Don’t Walk Away” to the musical number for “All Over the World,” in which Kelly brings some New Wave mannequins to life to go clothes shopping, and the messiest, most chaotic musical number in history ensues. At one point a man in spider-themed makeup crawls toward the camera between the cobweb nylon leggings of other dancers, as though auditioning for Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. Like the entire film, each moment is edited with the flashiest possible wipe, as supplied by your local high school A.V. club.

Sonny (Michael Beck) tries to convince Zeus to allow Kira to stay with him on Earth.

When Kira is summoned back to Mount Olympus, which is a garish Joust world of neon oranges, reds, and yellows, Sonny chases after her by roller skating at full force directly into a brick mural. (It’s easy to imagine what the alternate ending of Xanadu might have been.) Before the cosmic voices of Zeus (Wilfred Hyde-White, My Fair Lady) and Hera (Coral Browne, Auntie Mame), Sonny pleads the case for mortal love, and at last Kira is permitted to return to Earth just in time for the club’s opening. Newton-John performs a “Xanadu” medley while switching through various styles and costumes (hard rocker, country music singer, New Wave alien with a blue wig). It’s hard to come away from Xanadu questioning Newton-John’s talent. She can dance with Gene Kelly, hit every high note, swing about on roller skates, act the doe-eyed innocent in one scene and the sweaty sex kitten in the next. She’s as convincing a Muse as you’ll ever see in leg warmers. But what Xanadu as a whole inspires I leave up to you.