The signature haunted image of Mario Bava’s Gothic classic Kill, Baby, Kill (Operazione paura, 1966) is that of a child’s hands pressing the outside of a window. That, and the moonlight shimmering from behind the fingers, contrasting with the darkness from the inside of an empty inn after hours – that’s all it takes for Bava to drive the chills up your spine. A face comes up to the glass, a girl with straight blonde hair and the face of a doll, with overlarge eyes and an expression of – is she smiling? With cruelty? The little girl haunts a small Carpathian village, of the style to which we’re accustomed in these Gothics – overshadowed by an estate called Villa Graps, of which the villagers are too terrified to speak, and which might as well be Dracula’s castle. She is sometimes seen playing with a white bouncing ball. And if you see her, you’ll meet an unfortunate end, “bled to death under mysterious circumstances” as one character puts it. Before the opening credits, one woman, fresh from a ghostly encounter, impales herself on the spikes of a fence. One can only imagine that the phantom girl, one of the most memorable creations in a film chock full of dazzlingly surreal moments, inspired an almost identical ghost in Fellini’s “Toby Dammit” segment of the anthology Spirits of the Dead (1968). In that film, the ghost is Terence Stamp’s visualization of the Devil. Watching Kill, Baby, Kill, it’s easy to see why.

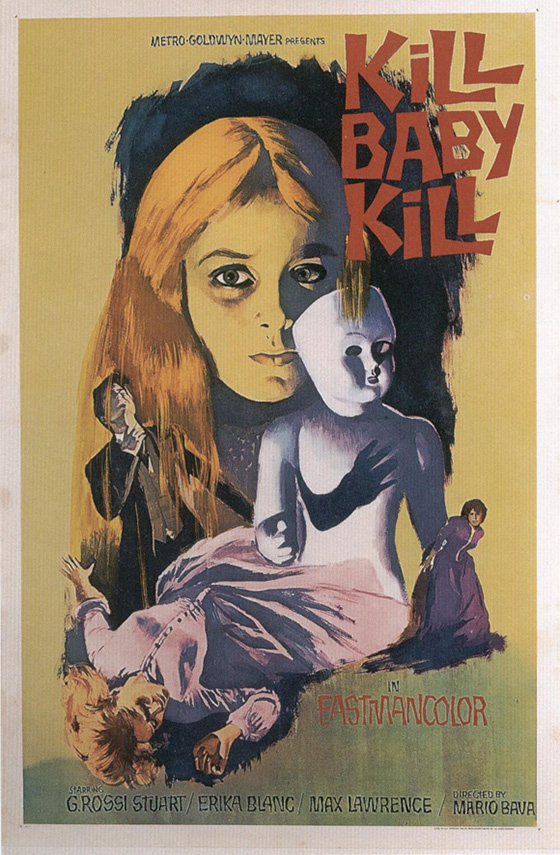

Paul (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart) confronts the terrors of the Villa Graps.

The mystery surrounding the ghost and the village curse must be solved by a skeptical young doctor named Paul (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart, The Last Man on Earth). Of course. There is usually a skeptical young doctor, and more often than not he’s named Paul. He has arrived in the village to perform an autopsy on the impaled woman, and he needs a witness, so he’s assigned a former student of natural sciences named Monica Schuftan (Erika Blanc, The Devil’s Nightmare). Exteriors were shot in the medieval village of Calcata near Rome, creating a claustrophobic, labyrinthine landscape of narrow alleys and archways and steep steps and high windows, as though M.C. Escher were the architect. The two witness the town bell ringing without anyone pulling the bell-rope. Maybe it’s the wind, they weakly suggest. But legend has it that the bell rings when someone is marked for death. A seven-year-old girl, Melissa Graps, bled to death while ringing the bell for help that never came. She had been accidentally trampled by horses during a drunken village festival many years ago – thus the curse. Now her mother, the Baroness Graps (Giovanna Galletti, Rome, Open City), never leaves the walls of the Villa Graps, surrounded by cobwebs, creepy dolls, paintings straight out of a Corman/Price film, and memories of her daughter.

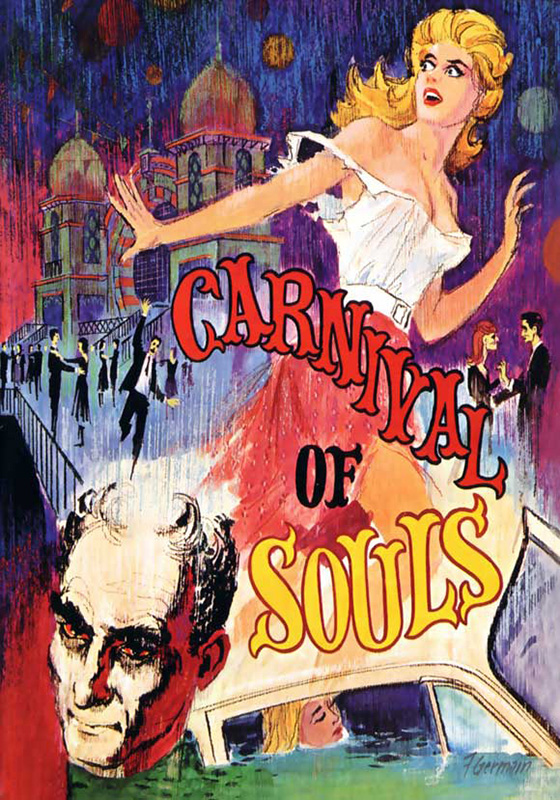

A doll appears inexplicably on Monica’s bed.

And those dolls! Bava makes the most out of one which appears to have been scalped by a hatchet. In a dream sequence he stretches them in funhouse mirrors as they lurch out of black shadows; and when the doll appears, the ghost of Melissa Graps is not far behind. Bava puts Melissa’s white ball to similar use, as we watch it come bouncing out of the ether, out of the Poltergeist dimension, in both the inn – where a young servant girl (Micaela Esdra) is tormented by the ghost – and in the villa, where it smacks its way down a spiral staircase that Bava lights in green, blue, and red. In Kill, Baby, Kill, Bava takes the viewer along a passage into the world of dreams, gradually, and it is in the Villa Graps that we find the boundary between dreaming and waking dissolved. Here are the corridors where Melissa Graps walks. Here is where, in a moment worthy of Buñuel, Paul suddenly finds that no matter how many times he passes through an exit, he cannot leave a room. He simply emerges on the other side of it. He tries again and again, faster, and sees his former self running ahead of him toward the exit. He tries to catch himself, reaching toward his own shoulder, and finally succeeding and overtaking. He turns, confronts himself, and sees his own face, but possessed of sinister triumph – a doppelgänger. As with the ghostly girl, it’s memorable enough to be copied (and played for laughs, in the X-Files episode “How the Ghosts Stole Christmas”), but it’s never as effective as it is here, for Bava is completely in tune with the logic and tone of nightmare.

The ghost of Melissa Graps.

Ultimately, there is more to the mystery than simply a ghost story – if it were straightforward, it would not be an Italian horror film. But nothing becomes too convoluted. Balancing Paul’s skepticism is a local sorceress, Ruth (Fabienne Dali, The Libertine), who tries primitive, brutal cures on those marked by the Graps curse, but ultimately is the only one who can stop the evil tainting the village. Her final confrontation with the Baroness is required, but ultimately less interesting than those moments in which Paul and Monica and wander through cemeteries of leaning tombstones, or walking the corridors and crypts of the Villa Graps, encountering everything Mario Bava can throw at them.