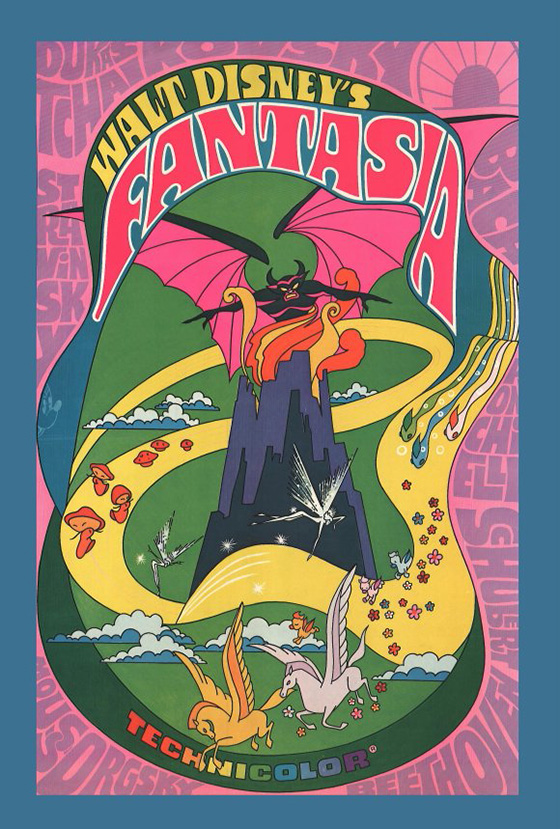

Fantasia (1940) is not an animated film, not by its own description. The film’s narrator, Deems Taylor – an announcer for broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera – describes what you are about to experience as “a new form of entertainment.” He stands in half-silhouette on a podium surrounded by an orchestra, whom we’ve just watched tune up, their instruments glowing in colors as musical notes are produced. He is not exaggerating, not with the perspective of 75 years, when the rarity of a film – no, a thing like Fantasia is all the more clear. Fantasia – whose title, according to The American Heritage Dictionary, refers to “a medley of familiar themes” – is more than just 125 minutes of animated segments to the accompaniment of classical music. It was meant to be a transporting, immersive experience in music and imagination: a simulation of sitting in the audience before a symphony orchestra while letting the mind wander through one strange daydream after another (no wonder the film was re-released in the 60’s with intentionally psychedelic poster art). Renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski of the Philadelphia Orchestra provided the music. Walt Disney provided the animation as well as the strategy of recording on seven tracks, ideally to be played in theaters outfitted with thirty speakers. As with the soundtrack, Disney intended the screen to envelop the audience, an idea anticipating Cinemascope. Even the ordinary Joe of Main Street USA, who could never afford to see a proper concert performance nor afford the finery to attend, would leave the theater weeping with joy at the beauty of classical music. And every few years, Fantasia would be re-released with new segments mixed with old favorites, like a touring musician mixing up his repertoire. Anyway, all that was the plan.

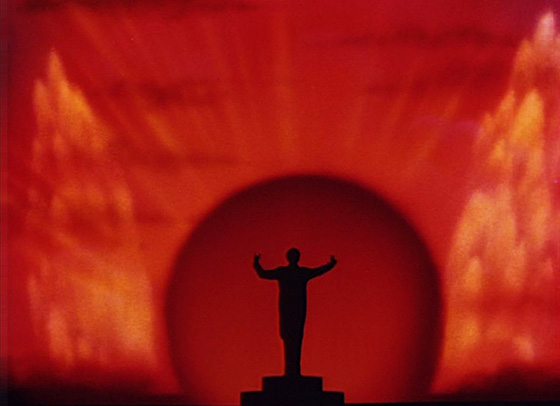

Leopold Stokowski conducts Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.”

In reality, the prophetic widescreen strategy never materialized, and the thirty speakers were so expensive to equip that they were utilized in only a select number of theatrical engagements. A sequel never arrived until Fantasia 2000 (1999), a belated gesture toward Disney’s original intention of a franchise. Nonetheless, Fantasia has always been much more than just a movie. It bore little resemblance to the studio’s previous films, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Pinocchio (1940). Apart from the “simulated concert experience” aspect, the film seemed to have higher aspirations: it has an educational slant, particularly in the longer road-show version with the spoken introductions by Taylor. He summarizes the composer’s intention for the music, and then how the Disney animators decided to interpret it. In retrospect, it’s amusing that Taylor has to explain what The Nutcracker is, stating that “nobody performs it nowadays”; Fantasia would popularize it again, to the point that now it seems every city has a Nutcracker production going at Christmastime. And generations of children have been introduced to the world of classical music via Fantasia, so, like Disney’s later educational films for 50’s television, there is a nobler goal in mind. When Taylor presents the opening piece, Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor,” he sets the stage for the entire picture, explaining that during this segment your mind will wander, at first conjuring images of the instruments as they play, and then drifting into more abstract shapes and bright colors. And then, naturally, we transition into more fantastic realms and stories. It’s like an instruction manual for attending classical music concerts: don’t let yourselves get bored – try doing this, kids.

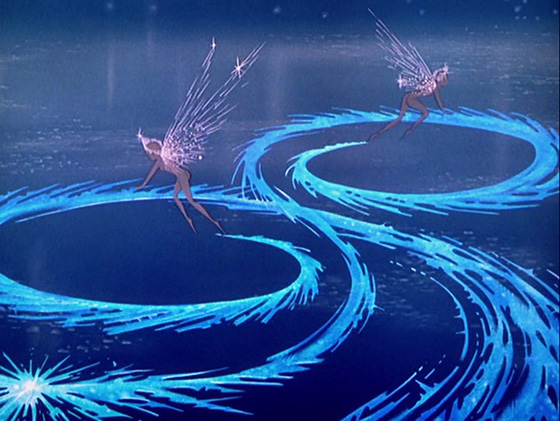

Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz of the Flowers” from the “Nutcracker Suite” sequence.

A major highlight of the film, the excerpts presented from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker are stripped of their narrative context and rejiggered with something technically startling and aesthetically marvelous. “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy” is set to yawning fairies summoning dew onto spider webs, and finally a collection of mushrooms, which shake off the dew to perform the “Chinese Dance.” As with every minute of Fantasia, the animation is superb: note that the littlest mushroom, struggling to keep up with the choreography, is painted in a lighter color so your eyes are drawn to it instantly. For the “Arabian Dance,” a goldfish darts shyly away from the creeping camera, scattering bubbles at the viewer while we explore submerged reeds and shadowy alcoves. Throughout Fantasia Disney makes the most of his multiplane camera (also well showcased in Pinocchio), which shoots through layers of painted glass to provide real depth. The technique will reach its apex with the film’s denouement, Schubert’s “Ave Maria.” But in the “Arabian Dance” sequence the animators also play with shadow and darkness, unafraid to dim the lights to near-pitch to make you peer through the layers at the twinkling animation – an element used again in the early scenes of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” when we witness the birth of life in the inky blackness of the ocean depths, and of course Moussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain.” The goldfish of “Arabian Dance” bring out the muted quality of the music, before their translucent tails form beautiful overlapping designs over their faces, like veiled women in a harem. In “Waltz of the Flowers,” fairies of frost ice skate energetically to the music before giant descending snowflakes twist in the light.

Mickey gets murderous when a broom gets out of control in “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.”

“The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” the most iconic segment of the film, was also the film’s genesis. In 1937 Walt intended to make a short film set to Paul Dukas’s hypnotic scherzo, but the budget ballooned, and the only way to turn a profit was to anchor it to a larger film – thus the birth of “The Concert Feature,” later to be titled Fantasia. Mickey Mouse, whose popularity was being eclipsed by Donald Duck (understandably), was always intended to have the starring role, and he was suitably redesigned – or, you could say, rebooted. Now he had whites in his eyes, to give him more expressiveness, but traces of his old mischievous qualities remained, thankfully. “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” is the story of youthful talent and ego run riot. Mickey, thinking he can be just as great a sorcerer as his master, brings a broom to life so it can complete his work for him – carrying buckets of water to fill a cistern in the center of the wizard’s cavernous, shadowy domain. While he sleeps, he dreams of standing atop a mountain and commanding the heavens and the seas, but he awakens to find the broom has filled the cistern to overflowing and won’t stop. Mickey picks up a giant axe and hacks the broom to pieces – which we see only in shadows traced against blood-red light. (Mickey is not to be messed with.) Alas, the fragments of broom come to life, forming an army that proceeds to flood the building. In particular I love the shot of the brooms several feet underwater, still mechanically dumping their buckets – set to their purpose, doing exactly what was asked of them, almost sinister in their blind obligation.

Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 6 (Pastoral)” is rendered in Greek mythology.

Oddly, Deems Taylor introduces Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” by insisting that it’s not art. Rather, this is science. Why can’t it be both? In fact there’s quite a lot of artistry to this segment, which is not short on ambition: it opens at the dawn of time, passing through gas clouds in the cosmos, before arriving at a primitive Earth tormented by volcanoes spewing lava. (Look at that lava. It’s all hand-drawn – every ripple, every flowing pattern.) The oceans ultimately overtake the volcanoes, and we are drawn deep below to witness the birth of life, first as single-celled organisms, then as miniature creatures consuming and taking advantage of one another in different ways, all in the interest of survival. We transition to the dinosaurs, and the pattern continues: the creatures almost casually preying on one another, until the arrival of a Tyrannosaurus – and a lightning storm – alters the mood, and everyone flees in panic. He can eat all of them. Prior to the storm sequence, the portrayal of the dinosaurs in natural lighting is interesting: they are often in shadow, just as you might see them if you came across them – they aren’t showcased like in King Kong (1933). They even behave as one might expect real animals to behave, lacking any cartoonish expressiveness, though we can still read their intentions clear enough. Eventually rapid climate change turns the oceans into deserts, and the few remaining dinosaurs scrabble over small pockets of water to drink, and wander dead-eyed through the desert like an animated version of Gus Van Sant’s Gerry. Intermission comes. The orchestra playfully improvises a jazzy tune, until a stern Taylor arrives, and the film resumes. In Beethoven’s “Pastoral Symphony,” we visit Mount Olympus, where winged horses play in the water or glide above it, before, in the most openly erotic sequence in the history of Disney animation, young “centaurettes” bathe and preen topless. (This remains uncensored – they don’t have nipples, after all – but home video releases do optically zoom certain shots to remove a racially-insensitive caricature. It’s a reminder that even this “timeless” classic is very much of its time.) Finally an alcoholic Bacchus cavorts in spilled drinks, and Zeus tosses thunderbolts from the skies before kicking off his sandals and pulling a storm cloud over his body to fall asleep.

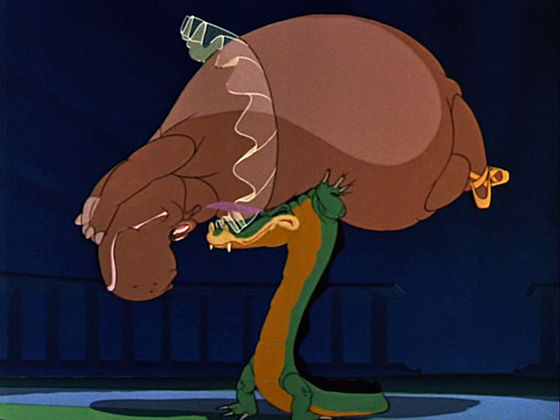

Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours” is given the satirical treatment by animator T. Hee.

Now, by this point, Fantasia is starting to drag. The film is more than half an hour longer than each of Disney’s previous animated pictures, and it seems longer because of the lack of dialogue and narrative. (Thus the use of an intermission in a film that’s just over two hours.) In its original road-show format, with thirty speakers (if you’re lucky) and the sheer spectacle of the exhibition, it would be a full-course, satisfying meal. When viewed on DVD or Blu-Ray in a living room, you’ll be forgiven if your attention has started to meander. In the 80’s, the classic Disney films were regularly cycled back into theaters, and my mother and older sister took me to Fantasia. The film broke during “Rite of Spring,” and I was annoyed because I wanted to see more dinosaurs. But my family saw the film’s breaking as a reprieve. Even in a theater setting, they weren’t digging it like I was. Later I was able to see more segments from the film when we subscribed to The Disney Channel (back when it was dominated by classic Disney animation, not tween sitcoms), and came to love the film’s remaining segments, including Ponchielli’s “Dance of the Hours” and “Night on Bald Mountain.” Here, the film’s tempo picks up again. “Dance of the Hours” makes the most of the no-dialogue-just-match-the-music dictum, sending up ballet with comically grotesque animals – ostrich, elephant, hippo, gator – performing a dance of lust (or just hunger) that alternately defies gravity and brutally succumbs to it. There’s more than a trace of Loony Tunes humor here. This is a short that ought to have brought applause during its theatrical screenings, rousing any audience members who were previously drifting off.

The spirits ride on Walpurgis Night in Moussorgsky’s “Night on Bald Mountain.”

“Night on Bald Mountain” presents us with one of the great Disney “villains,” the giant demon Chernabog. At first we just see Bald Mountain, before we realize that its peak consists of two great bat-wings, unfolding to reveal the towering embodiment of evil. His shadow stretches as a physical thing to engulf the town below – what must be an homage to a similar image in F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). It’s Walpurgis Night, and the spirits and devils come forth to cavort, riding the fell wind up to Chernabog and dancing in the flames of the mountain. In his claw, he transforms beautiful fire-sprites into deformed creatures. Naked harpies and other phantoms circle in a delirious haze. At last church bells are heard, pulsing a light from which Chernabog and his minions shrink, and the wings fold back to form the summit of Bald Mountain again. Below, a procession holding candles moves over a cathedral-shaped bridge, and into cathedral-like trees, while Schubert’s “Ave Maria” plays – held, profane, for a lingering time until the animation ceases entirely, and we simply stare at a painted dawn and listen to the choir music. The curtains are closed. I think back to a moment, much, much earlier, when Mickey Mouse is happily conducting for his broom, his white-gloved fingers gliding back and forth while the broom marches in a dance, and Mickey, instructing the broom, dances himself. He is casting his spell, but he is also dancing to “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” Right there, in the animator’s brush, is the purpose of Fantasia: music is a magic spell.