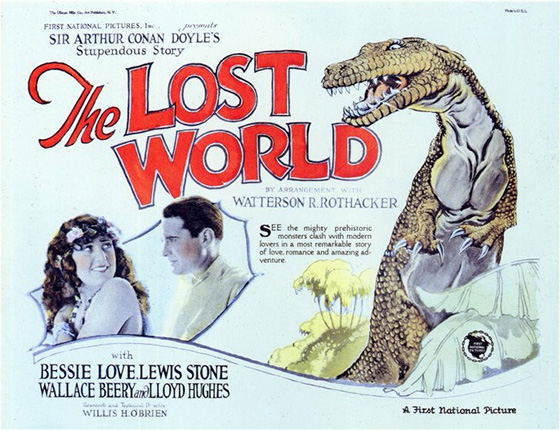

When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published The Lost World in Strand Magazine in 1912, he was allowing his name to be associated not just with his creation Sherlock Holmes, but with the likes of speculative fiction authors H. Rider Haggard and Jules Verne. The first in a series of novels and short stories featuring the headstrong Professor Challenger, The Lost World was sprung upon the public in the same year that Edgar Rice Burroughs began publishing his fiction; Burroughs would go on to explore the “lost world” genre exhaustively, uncovering lost tribes and prehistoric creatures in the jungles of Africa or in our Hollow Earth, the land of Pellucidar. So Doyle, whose novel proposed a plateau of dinosaurs and ape-men in an unexplored region of the Amazon, was engaging in a tradition but also perfecting a template for others to follow, and the film adaptation, released thirteen years later, served a similar role for monster-movie spectacle. The Lost World (1925), directed by Harry Hoyt, is most notable for featuring stop-motion dinosaurs created by Willis O’Brien. O’Brien’s work here would ultimately lead him to King Kong (1933), whose influence on fantasy cinema – or blockbuster films in general – cannot be understated. But The Lost World was a significant stepping-stone, and a huge hit in 1925, providing eager audiences the opportunity to see creatures like the Allosaurus, Brontosaurus (Apatosaurus), Stegosaurus, and Triceratops parade by while Professor Challenger (Wallace Beery, Robin Hood) and his small group of explorers gape in wonder from the corners of the screen, true audience surrogates.

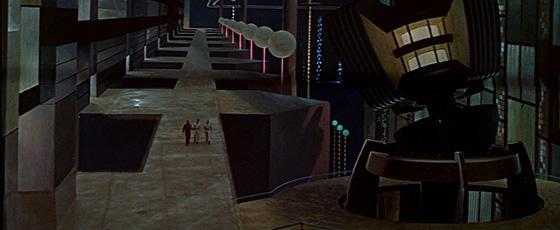

The plateau of the Lost World, as the explorers cross to it from a felled tree.

The screenplay, by Marion Fairfax and an uncredited Charles Logue, is reasonably faithful to the novel, inserting a love interest in the form of Paula White (Bessie Love, The King on Main Street), as well as a climax featuring a Brontosaurus rampaging through London (in the book, Challenger brings back a live Pterodactyl as evidence of his journey). Paula White is the daughter of Maple White, an explorer who claims to have discovered a lost world in an unexplored region off the Amazon River. Challenger, angrily defying the ridicule of his peers, says he will volunteer Maple White’s map to those who will form an expedition. Volunteers come in the form of great white hunter Sir John Roxton (Lewis Stone, The Prisoner of Zenda), the skeptical Professor Summerlee (Arthur Hoyt, the director’s brother), Paula White – who wishes to find her missing father – and young reporter Edward Malone (Lloyd Hughes, The Sea Beast), whom the journalist-loathing Challenger wrestles down a staircase. The team is advised to unseal the map only when they’ve traveled to a certain location up the Amazon, but when the envelope reveals a blank sheet of paper, they’re at an impasse – until Challenger arrives with the map in hand, declares himself leader, and guides them the rest of the way upriver to the towering plateau, where a “Pterodactyl” (actually a Pteranodon) soars overhead. Scaling the sheer walls is impossible, but they follow Maple White’s path (shades of Journey to the Center of the Earth‘s Arne Saknussemm) by climbing an adjacent spire, felling a tree, and crossing it. Alas, after they span the bridge a Brontosaurus knocks the tree down the cliff, stranding them in the Lost World.

A sinister ape-man is shot in the arm by the expedition.

The novel’s hostile tribe of primitive ape-men is reduced to a single man in a shaggy suit, who first tries to dissuade the intruders by toppling a boulder at them while they camp at the base of the cliffs, and later tries to attack Edward before Sir John shoots him in the arm. The ape-man’s grotesque makeup seems like it belongs to Island of Lost Souls (1932) more than 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but it does provide some variety to the rogues’ gallery of O’Brien’s model work. And there are plenty of models on display, including a jungle of swooping Brontosaurus necks, a Stegosaurus, a family of Triceratops, an Allosaurus constantly on the prowl (he’s described as a “pest”), and a Tyrannosaurus Rex. Challenger turns a tree into a catapult as a means of defense, but only uses it to launch Summerlee in the air, ending their dispute as to whether the flight will describe a curve or a parabola (Challenger’s assertion is correct, and Summerlee is dunked in the river). Despite his engagement to the fickle Gladys (Alma Bennett) back home, Edward falls for Paula and they ask Summerlee to preside over their marriage. Sir John discovers the skeleton of Paula’s father in a system of caves, bringing her quest to a sad end, but searching the caves also provides a way off the plateau; the ape-man tries to kill them during the escape, before he’s shot for good. Finally, Challenger’s attempt to bring a live Brontosaurus back to London backfires when the creature gets loose, destroying London Bridge and last seen swimming the ocean.

The Brontosaurus escapes his London captors.

Arthur Conan Doyle, who is seen at the opening of the film, was so impressed by O’Brien’s stop-motion effects that, three years before the film was completed, he showed the animator’s experimental films to the Society of American Magicians. As stop-motion authority Mike Hankin writes in his O’Brien chapter of Ray Harryhausen: Master of the Majicks, Volume 1 (2013), “Refusing all questions on how the footage was created, he left the audience bewildered (sweet revenge for constantly being baffled by their tricks).” Doyle then wrote a letter to his frenemy Harry Houdini explaining – as though it really needed to be said – that the dinosaurs were a hoax of his own. (Houdini and Doyle were at opposite ends of the debate over spiritualism; Houdini made it an obsession to expose mediums as frauds, but Doyle was a firm believer. It appears that Doyle used Willis O’Brien to get back at Houdini.) But stop motion wasn’t new, as O’Brien had already collaborated with Herbert M. Dawley on The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918), a short which features stop-motion dinosaurs, and Dawley went on to make a sequel, Along the Moonbeam Trail (1920), which he animated himself. Prior to this, O’Brien had animated for Thomas Edison’s film company. Nonetheless, The Lost World was a significant step forward in the art, being a feature-length film combining actors with stop-motion effects. By comparison to King Kong, the quality of stop-motion in The Lost World is variable: some scenes are much smoother than others. The models are also not quite as refined or detailed. But they are abundant. Once the explorers reach the plateau, there are dinosaurs everywhere, because it is obvious what moviegoers had come to see. This exuberance for prehistoric fantasy would be exceeded in King Kong, with the added benefit of awe.

Willis O’Brien animates a dinosaur battle.

The Lost World may have been a popular hit – it was the first in-flight film ever shown (in April 1925) – but the original ten-reel roadshow version disappeared after 1929, when prints were ordered withdrawn and destroyed by the rights-holder, the widow of the film’s co-producer Watterson Rothacker of the Rothacker Film Manufacturing Company. For decades only a drastically shortened version of the film survived, stored at the George Eastman House. Finally, in 1992 an almost-complete print was discovered in the Filmovy Archiv in Prague. According to Silent Era, “In 1997, George Eastman House debuted the almost wholly reconstructed Lost World, which now totaled more than 8000 of its original 9200 feet. Of the missing footage, most of it remains lost in the form of minor print break splices, damaged reel ends and shortened running times on intertitles (which ran long for slower-reading contemporary audiences). Among the still-missing footage is the cannibal attack sequence in the Amazon jungle.” A 2001 DVD release uses this reconstruction as well as other sources including alternate footage from the production’s right-hand camera, intended for a foreign-release negative, to provide even more missing material (but no cannibal attack). Although the film is still not entirely complete, it flows well and we can count ourselves lucky to have at least 86% of the original version. It remains an enjoyable picture, and Doyle, who died five years after its release, had something to be proud of – despite the cringeworthy use of a blackfaced character (but such was 1925, and Doyle’s novel wasn’t short on Colonialist racism either). Kong would eclipse The Lost World, but nonetheless its first, dinosaur-addled half feels like The Lost World redux. I also find it interesting to note that Doyle’s novel features a “dinosaur pit” of horrors that is uncannily similar to the lost “spider pit” sequence in Kong. Subsequent B-movies such as Lost Continent (1951) and King Dinosaur (1955) demonstrate a Lost World influence, and the story was adapted again in 1960 by Irwin Allen (with Claude Rains as Challenger), and then 1992 (with John Rhys-Davies), 1998 (with Patrick Bergin), and 2001 (with Bob Hoskins). A syndicated series of the same name ran from 1999-2002. Michael Crichton paid tribute by titling his Jurassic Park sequel The Lost World, adapted into a film by Steven Spielberg in 1997. In homage to Doyle, perhaps, Spielberg climaxes his film with another dinosaur on the loose in a modern setting, in this case a T. Rex in San Diego.