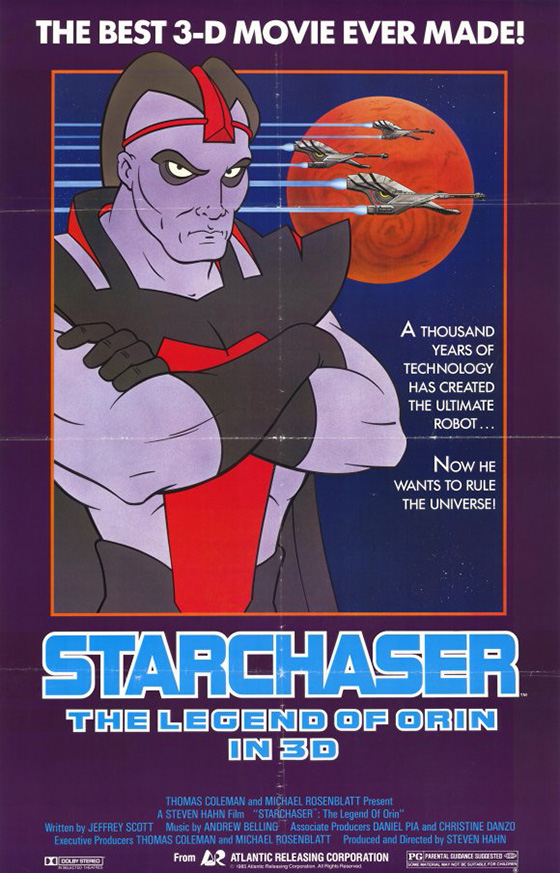

When I first watched Starchaser: The Legend of Orin (1985) on VHS sometime in the late 80’s or early 90’s, I thought it was going to be an anime. This was born from experience as a young video store patron: most science fiction animated films that I’d never heard of before turned out to be Japanese. I had mixed feelings on the prospect. On the one hand, the sex and violence in anime were edgier than in American fare, and as R-rated rentals were out of the question, I was on the make. But the tapes were always badly dubbed and the plots sometimes incoherent (often hacked down from a longer, complex series into a single feature). So here was a film that was new to me, with a character on the cover art (villain Zygon) who looked manga-esque, and a PG rating instead of the standard Disney G. It had to be Japanese. Lo and behold, the film was American. Characters swore and shot holes in each other. How had this escaped my notice for so long? I’d certainly heard nothing of its theatrical release, as I would have dragged my father: I made him take me to He-Man and She-Ra: Secret of the Sword the year Starchaser came out; this was a higher quality product and right up my alley. He-Man and She-Ra offered free comic books at screenings, but Starchaser was in glorious 3-D! I liked Starchaser well enough to dub myself a copy using the VCR-to-VCR method, and I watched it religiously for a few years, scratching that SF animation itch. So how does the movie hold up decades later?

A Man-Droid traps Orin.

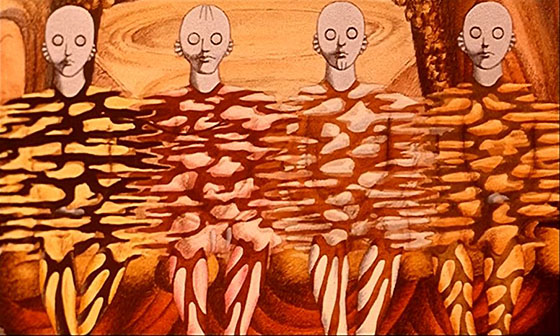

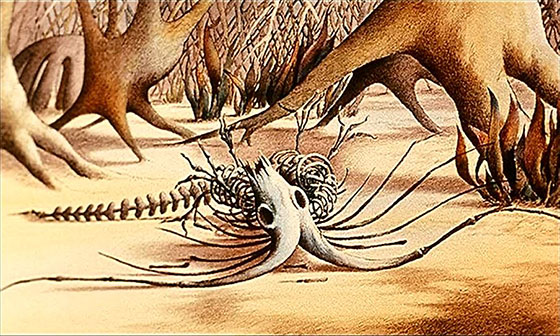

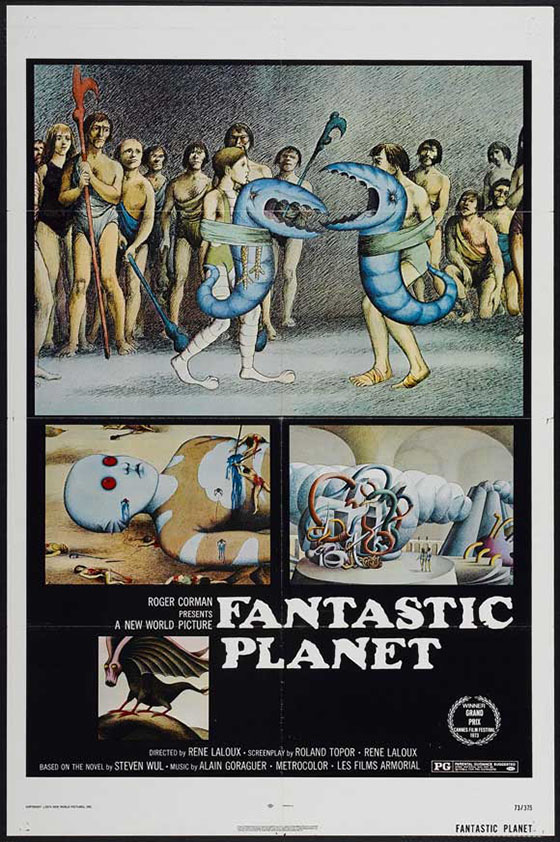

Not so great, but, you know – nostalgia will make so much endurable. The plot is perfect cardboard. Orin (Joe Colligan) is one of many slaves in a vast mine, digging for valuable crystals without ever glimpsing the sun while worshiping a Darth Vader/Thulsa Doom/Zardoz being named Zygon (Anthony De Longis), who greets them from what looks like the Temple of Doom set. One day Orin discovers a sword in the rocks, which beams out a hologram image of a Moses-like figure promising a fabulous world above to which the slaves can escape. The sword’s blade disappears, leaving only a golden hilt. When Zygon discovers Orin has this mystic artifact, he tries to take it (after physically strangling Orin’s girlfriend to death), but Orin evades Zygon’s robot guards and digs his way to the surface using his laser drill. In the film’s most striking sequence, Orin journeys through an eerie alien swamp reminiscent of René Laloux (Fantastic Planet) before encountering horrific Man-Droids, who capture Orin and threaten to dismember him so they can appropriate his parts into their mangled bodies: Heavy Metal meets The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. But the hilt still contains an invisible blade, on which the Man-Droids accidentally skewer themselves. Orin takes his magic sword and runs, rescued by cigar-chomping space smuggler Dagg Dibrimi (Carmen Argenziano), who differentiates himself from Han Solo by smoking a cigar and calling himself Dagg Dibrimi.

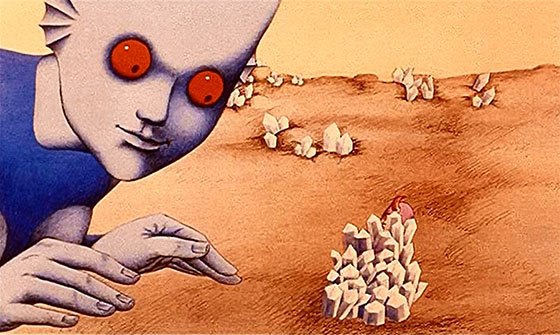

Aviana discovers Orin’s unconscious body.

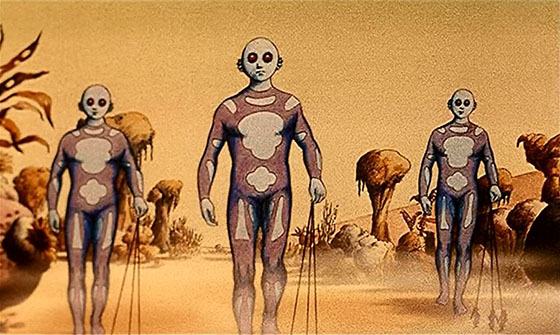

You could write the rest yourself. Orin joins Dagg’s ship, the Starchaser, along with mismatched, bickering allies who join them along the way: a Tinkerbell-like ball of light called a Starfly; the ship’s prissy A.I., Arthur (Les Tremayne); a rich girl named Aviana (Noelle North) and her robot bodyguard; and, most disconcertingly, Silica (Tyke Caravelli), a “Fembot” who lusts for Dagg after he reprograms her via the derriere. Eventually Orin finds his way back to the underground mines to kill Zygon and liberate the slaves. Everything here feels like it came from some other movie, but obviously Star Wars is the dominant influence. The Imperial March seems about to break out every time Zygon makes an appearance, and Orin’s magic sword, with its invisible blade, is an ersatz lightsaber, cutting through steel doors and deflecting blasters. When Orin finally learns that he didn’t need the hilt because the blade was projected from inside himself, he laments that it was so simple he couldn’t see it – but the viewing audience, well familiar with the Force, certainly could see it coming.

Zygon seizes the magic sword.

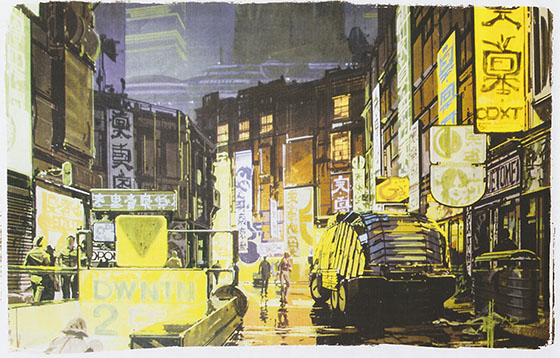

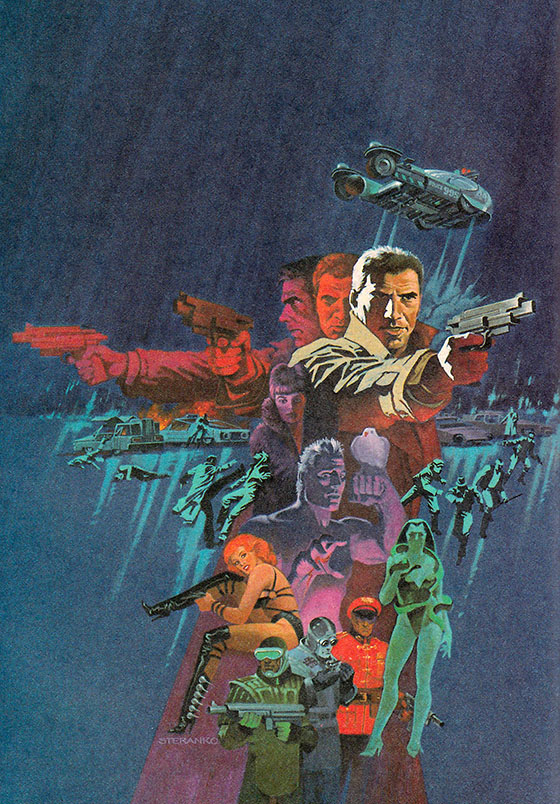

Hand-drawn animated films take time, so perhaps it’s not Starchaser‘s fault that it feels a bit late: late to 3-D (the 80’s 3-D boom was on the wane), late to the Star Wars bandwagon (the original trilogy had ended, and anyway Roger Corman had already oversaturated the market with B-movie rip-offs), and even late to adult-oriented American animation following Ralph Bakshi and Heavy Metal, both of which seem to have partly inspired this film. If the movie were more adult – say, a PG-13 at least – it might have been more interesting, but undoubtedly it’s a movie that will be enjoyed the most by indiscriminate kids, such as the younger me. Though the plot is unimaginative and the synth-driven score sounds cheap, the film is worthwhile if only for its animation, which integrates computer rendering rather smoothly with traditional methods. (How this all looked in 3-D, I have no idea, though I’d imagine it enhanced the experience.) Director Steven Hahn was an animation veteran, having worked on some of Bakshi’s films as well as the Droids Saturday morning series, which I also enjoyed as a kid. With Starchaser, ambitions were clearly high, and some of the action scenes and character moments are handled well, but on the whole this is one of those 80’s animation oddities, alongside the likes of Rock & Rule (1983): not quite a cult classic, but strange enough to stick in the memory.