“This is the universe. Big, isn’t it?”

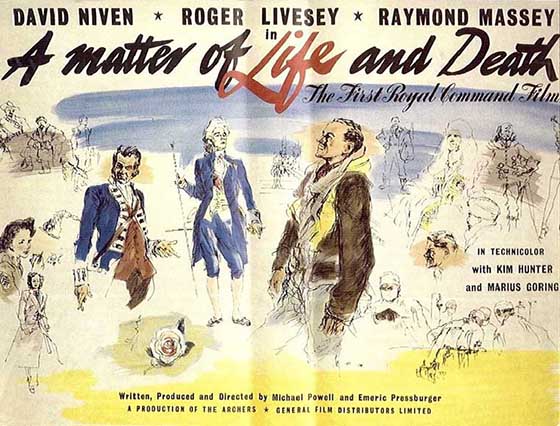

So opens A Matter of Life and Death (aka Stairway to Heaven, 1946), one of the finest films from the acclaimed British filmmaking team known as the Archers – director Michael Powell & writer Emeric Pressburger, who co-signed each of their films as equals – and which also happens to be one of the greatest films ever made. Certainly, it ranks high in my personal top 10. And any film which opens with a depiction of the universe in all its vast glory is not without ambition. Come to think of it, the American contemporary It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) opens in a similar manner, taking us from the microscopic (Bedford Falls) to the cosmic in the span of seconds, as prayers for George Bailey reach Heaven, which we only see as stars flashing at one another through the blackness of space like some kind of celestial Morse code (“Well, we’d better send someone down”). A Matter of Life and Death, with jaw-dropping production design by frequent Archers collaborator Alfred Junge (The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Black Narcissus), will eventually deliver on showing us a more literal afterlife, most notably a stairway to Heaven which rises like an escalator through the clouds, past monolithic statues of some of the great wise men of history: Abraham Lincoln, Plato, King Solomon. This film isn’t short on awe. But, like It’s a Wonderful Life, it also has its eye on the relatively microscopic, the everyday, which it treats with just as much wonder. RAF captain Peter D. Carter (David Niven) has fallen in love with a beautiful American girl, June (Kim Hunter), a simple fact that brings the cosmos to its knees. Heaven is a world of stark contrasts, and is therefore filmed in black & white. “One is starved for Technicolor up there!” says Conductor 71 (Marius Goring, The Red Shoes) wistfully as he dissolves from Heaven to Earth, and the black & white rose on his lapel becomes a deep pink (you’ll also notice that a breeze flutters its leaves, as though everything about him is finally coming to life). It’s a reverse Wizard of Oz. Our world has a lush quality which Heaven is lacking. It’s a wonderful life here – but Niven has to fight to hold onto it.

Radio operator June (Kim Hunter) connects with RAF Captain Peter Carter as he prepares to dive from his fiery plane without a parachute.

On May 2nd, 1945, at ten after four o’clock, June, a radio operator from Boston stationed in England, receives a distress call from Peter, pilot and last survivor of a bomber plane that’s about to go down in flames. All his crew has bailed out, his friend Bob Trapshaw (Robert Coote, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir) is lying dead at his feet, and he has no parachute, but he must jump. While she tries to assess the situation, he continues to tell her it’s hopeless, and is more interested in reciting poetry and asking her if she’s pretty (one of the most heartbreaking moments in the film is when she awkwardly answers, “Not bad…”). It’s a love affair born in the last minutes of his life. It’s also one of the classic moments in Powell & Pressburger’s filmography. While Pressburger’s dialogue stampedes forward with wit and stoicism (perfectly delivered by the ideally cast Niven), Powell shoots Hunter’s isolation with a pulsing red light to match her red lipstick, and intense close-ups as she stares forward at nothing, listening to Niven’s voice resolutely dictate a message for her to deliver to his mother, confronting death with the knowledge that he’s another WWII statistic. He promises to come see her later: “You’re not frightened of ghosts, are you?” And when he leaves her to make his fateful jump, the sound of the roaring engine suddenly cuts out, and we hear nothing on the soundtrack but a ticking clock. Few films contains moments so spellbinding.

The military base prepares an amateur production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”: “That’s not the way to spell ‘Shakespeare.'” “Who are you, his agent?”

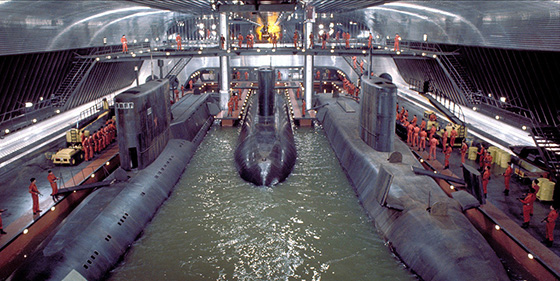

But this, of course, is not the end for Peter D. Carter. In the black & white Heaven, angel wings await new owners, hanging on racks like a laundromat. Bob Trapshaw waits in the lobby, refusing to sign in (those who do are asked to give their name and rank), because he’s expecting Peter to walk in at any moment. An angel (Kathleen Byron, Black Narcissus) takes him to look down a portal at the Records Office, a vast array of buildings that seem to be a mile below and which contain files on every human being ever born. She describes the duty of those working to keep track of all these files. A recent arrival, clutching a new pair of wings in his arms, stares down through the portal and says in wonder: “It’s Heaven, isn’t it?” Byron turns to Trapshaw and says, “You see? There are millions of people on Earth who would think it heaven to be a clerk.” But the error is soon uncovered: Peter has been invoiced but hasn’t checked in. Conductor 71, a gentleman beheaded in the French Revolution, is assigned to find the missing RAF pilot. Back in the world of color, we see Peter waking on an empty, idyllic beach. A nude child plays Pan pipes amidst goats. A dog runs up to Peter, and he says, “Oh, I’d always hoped there would be dogs!” Naturally, he thinks he’s passed into the afterlife (when he sees a “Keep Out” sign at one edge of the beach, he immediately obeys and turns about, apparently thinking the order comes from God). But, no, he’s still in England, outside a village where June herself is stationed. Somehow they recognize each other at first sight, and they kiss. All is right on Earth, just not in Heaven. Within the space of a few days he assimilates himself into her world. He meets her friend, Frank Reeves (Roger Livesey, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp), a village doctor with a brilliant mind who enjoys spending his afternoons working his camera obscura to observe the villagers from a heavenly point-of-view (a direct visual parallel is made to the portal through which Byron looked down upon her vast files on humanity). Alas, his audience consists of two bored cocker spaniels. Elsewhere, amidst an Eden of roses, Peter and June lounge in the grass, when suddenly time stops, and the Conductor appears to escort Peter back to where he belongs. Only Peter doesn’t want to leave. It was Heaven’s mistake, not his. With this unexpected wrinkle, it’s decided that the only possible resolution must come with a trial in three days’ time. As the deadline approaches, Peter becomes more distressed. Dr. Reeves diagnoses him with a neural condition and schedules an operation. He takes Peter’s upcoming “trial” very seriously – only he is looking for an earthly solution to his problem. He believes that it is a matter of life and death, because this medical condition might permanently cost Peter his sanity.

Conductor 71 (Marius Goring) is tasked with delivering Peter to the afterlife.

Much has been made of the film’s suggestion that Heaven and the climactic court trial exist solely in Peter’s mind. The opening scrawl tells us: “This is a story of two worlds, the one we know, and another which exists only in the mind of a young airman whose life and imagination have been violently shaped by war.” But the screenplay is too sophisticated to let itself fall into a simple analogy (John Bunyan, author of Pilgrim’s Progress, is briefly glimpsed in the film, but thank heavens this film isn’t as literal as his turgid work). We do not always see Heaven from Peter’s point-of-view; he isn’t present in the early scenes, as the angels scramble to discover their missing person and Conductor 71 is assigned to the case. We don’t get a proper explanation of how he could have survived his jump. All this complicates such a reading. It’s only late in the film that a parallel is drawn between his need to “win his case” before the celestial High Court and the struggle against his neural condition, which becomes most explicit when the stairway to heaven descends upon the operating room where the surgeons are at work. The frustrating thing about such simplistic interpretations (it’s all in his mind!) is that it seems to have the ulterior motive of dismissing the stakes which the story has laid out. This is a matter of life and death, regardless of whether or not Conductor 71 is real, or if that smell of fried onions that accompanies his appearance indicates some neurological condition. Besides, the films of Powell & Pressburger, particularly in this glorious stretch in their career (the film is sandwiched between I Know Where I’m Going! and Black Narcissus), are pure cinema. Just as Conductor 71 winks at the film’s use of Technicolor, almost breaking the fourth wall, this is a movie that exists in movie-land, with canted angles, a romantic score (by Allan Gray), beautiful cinematography (by Jack Cardiff), and sprawling sets with hundreds of extras in costume. It’s a movie where Peter and June can fall in love with only their words over the span of a few minutes, and recognize each other at once when they, rather coincidentally, come across each other on a country road. It’s all of a piece with angels, because, as the Archers have shown us time and again, cinema can be Heaven.