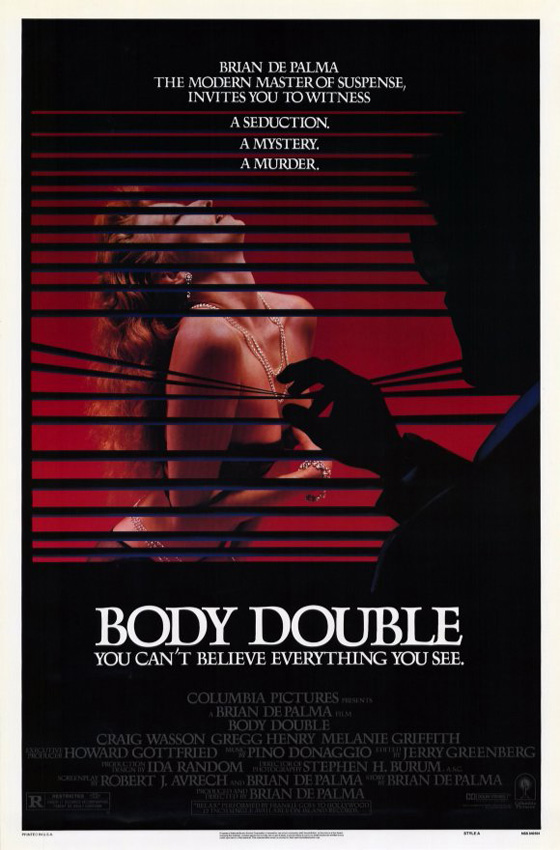

If you’re celebrating the new, extras-packed Phantom of the Paradise Blu-Ray from Shout! Factory’s Scream Factory imprint, you could expand your evening to a double feature by pairing the rock musical/horror/comedy with another Brian De Palma experiment in Hollywood meta, Body Double (1984). Ten years after Phantom, De Palma continued to send up genre cinema with this film which opens with a vampire experiencing paralyzing claustrophobia in his coffin. It’s quickly revealed this is struggling actor Jake Scully (Craig Wasson, Ghost Story), and his claustrophobia loses him the lead role in this cheap B-picture (directed by a very recognizable Dennis Franz). Even the opening titles make clear De Palma’s double-purpose with Body Double. The credits are those of a 60’s Hammer film – very Brides of Dracula – but the letters dissolve into the more stately font of a straight-faced 80’s thriller. One is reminded of De Palma’s better-loved Blow Out (1981), which opens like a slasher movie before pulling back to reveal those in the editing suite watching it. But in Body Double, the curtain is only apparently pulled back. Scully soon finds himself involved in a thriller straight out of Hitchcock; in fact, De Palma expects you to know the plot is an amalgam of Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). In many ways, Scully’s crossed from one movie set to another. This level of artifice gives De Palma carte blanche to indulge his perpetual love of Hitchcockian style, while sending up the genre of “erotic thriller” which was in vogue at the time, a genre that resurfaced again in the early 90’s post-Basic Instinct.

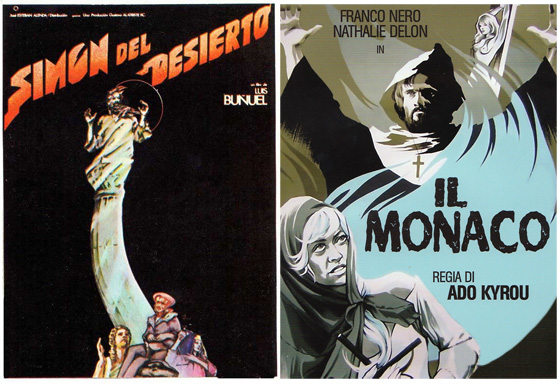

Gloria Revelle (Deborah Shelton) encounters a driller killer.

As a mystery, Body Double is actually fairly easy to decipher – at least for those who have seen a few Hitchcock films. After he catches his girlfriend (Barbara Crampton, Re-Animator) in bed with another man, Scully accepts the offer of Sam (Gregg Henry, Just Before Dawn), a fellow actor, to stay in a house he’s been renting, an elevated Space Needle-style watchtower with a lush, black-walled suite, adorned with a rotating round bed, an aquarium, a wet bar, and binoculars that look down on a neighboring house where a beautiful brunette does a striptease before the open windows every night. He soon notices that another man is watching her, who will be known only as “The Indian.” The woman is the wealthy Gloria Revelle (Deborah Shelton), trapped in a loveless marriage with an apparently abusive husband. When Scully sees the Indian trailing Gloria to a shopping mall, Scully follows, but loses sight of his goal – as when Gloria stops at a lingerie shop and tries on a pair of panties behind a half-open curtain. The woman working the register sees him and calls mall security. Before Gloria leaves the mall, she reconsiders her purchase, and drops her shopping bag in the trash; Scully retrieves the silk panties and stuffs them in his pocket. De Palma makes it clear that Scully is as much of a stalker as the hulking “Indian” is, and his motives are just as dubious. Finally he witnesses the woman’s murder by the drill-wielding Indian, crossing from James Stewart-binoculars-voyeur to participant when he breaks into the house in a vain attempt at rescue. When the detective arrives, there’s something about Scully that bothers him. De Palma can’t resist a pan down to Scully’s pants, and the stolen panties sticking from his pocket. Our hero, ladies and gentlemen.

Jake Scully stalks a stalker.

You could read Body Double as a serious erotic thriller, but it would be a mistake. For one thing, the sexual metaphors are gleefully obvious, from the nearly-obscene hot dog stand where Scully grabs a bite to eat to the over-the-top phallic imagery of the drill wielded by the murderer, finally escalating to an 80’s porno underworld so exaggerated and dream-like that it could never possibly have existed. (For one thing, the porno shoot is also a Frankie Goes to Hollywood music video, because why not?) Body Double is indeed a dream – or at least the ambiguous ending implies it could be. Reading the film as the wet dream of its sexually obsessive, psychologically damaged, claustrophobic protagonist – the film makes considerably more sense and the humor seems that much more effective, and prevalent. When Scully finally speaks to Gloria, they immediately melt into one another in a dizzying session of liplocking and heavy petting while De Palma’s camera spins around them over and over and over again. It’s such an absurd sequence (they have no reason to kiss; in fact, she has every reason to issue a restraining order against him) that it plays better when you view it as parody. In light of the idea that this may all be playing out in Scully’s imagination, it’s parodic but logical. Just as Scully finds himself in the midst of a Hitchcock film, he finds his erotic fantasies playing out like the late-night smut he’s watching on the rotating bed, lonely and depressed. But De Palma can’t resist commenting: during the Frankie Goes to Hollywood music video/porno shoot (“Relax! Don’t do it! When you want to come!”), De Palma casts Scully as a nerdy, glasses-wearing poindexter hooking up with the girl of his dreams; in the next scene he’s incognito, a greasy porno producer promising that same girl – one Melanie Griffith, here playing “Holly Body” – a starring role in his latest opus. He’s a character actor moving from one part to the next, but De Palma is only too happy to apply each label: the nerd, the sleazeball, the voyeur.

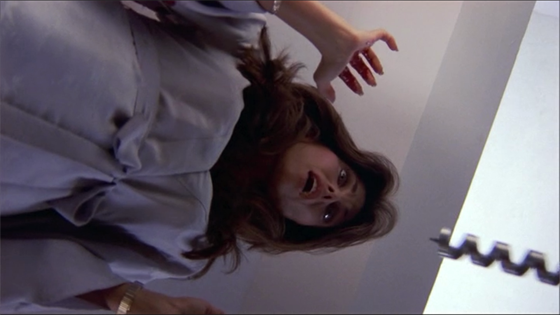

Melanie Griffith as Holly Body

Griffith is very amusing – and uninhibited – as Holly Body (perhaps related to Mr. Body from Clue?), a porno star with a limited vocabulary for which she overcompensates with street smarts. A scene in which she switches into negotiating mode, and describes all the acts which she won’t do for Scully’s proposed porno while he subtly blanches, signals the film’s transition into more overt satire, as does the trailer for her latest film, Holly Does Hollywood (a riff on Debbie Does Dallas), which looks like something out of The Kentucky Fried Movie. “Holly keeps this business where it belongs – IN THE GUTTER. Screw Magazine.” (The porno actress introducing the trailer, in some kind of Playboy Channel-style program, says she’s an “expositionist” before her partner gently corrects her: “exhibitionist.”) Holly Body is the body double of the title, hired to do the striptease to draw Scully’s attention to the window every night – so he can witness the murder of Gloria Revelle. The solution to the mystery is exactly what you expect it to be – Scully’s been set up. But more interesting is its resolution: De Palma cuts back to that horror movie set with Dennis Franz, Scully still afraid of that coffin, but equally afraid of getting fired. Then De Palma returns to the climax, but by now our faith in the reality of what we’re seeing has been critically undermined. So is this all a dream – a claustrophobia-induced panic attack stretched to two hours, a scuttling retreat into Scully’s Id? Does it matter? During the ending credits roll, De Palma simply shows us how body doubles get work: while Scully holds his position, one actress is traded for another (smacking gum), allowing for a simple edit so we can see the blood of the vampire’s bite seeping over naked breasts. Even in the film’s final moments, he’s giving the audience the smut it wants while underlining that it’s all really just a con, and the audience, like Scully, is the mark.