First off, this list is entirely personal. You will have 100 of your own. The intention is to draw a broad outline of fantasy films since the start of cinema in hopes that the reader might find some helpful recommendations. It’s an admittedly ludicrous endeavor to define 100 of the most essential of anything, which is why this is just “100 Essential Films of the Fantastic,” not the most essential. To pare this last down to 100, I found myself discarding many acknowledged classics, and holding tight to others for the sake of variety or my own passion for them.

To define what I mean by “Films of the Fantastic”…

Science fiction films are automatically considered eligible since they take place in the realm of “what if.” Horror films are eligible only if they contain at least one element of the fantastic. For example, John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) might be considered due to the last scene in the film, which implies the supernatural, though Halloween III (1982), fitting the above criteria more fully, makes a more interesting and perhaps more worthy candidate for this list. I found myself removing some major genre films from the list for the simple reason that the fantasy elements were too fleeting, or perhaps questionable (such as Jack Clayton’s The Innocents).

The era is taken into consideration. Today big-budget fantasy films are common. Although one might argue that Chandu the Magician (1932) is not as good a film as the latest multi-million-dollar superhero movie, it’s an exemplar B-movie of its era and uncommon in many ways; today FX-laden pulp movies are so everyday that, for the purposes of this list, I have the luxury to be picky. My intent is not to compare films from different eras but to celebrate those fantasy films which are outstanding for their time.

I could easily name 100 other films instead of these, but – as is the nature of these things – for the moment these are the ones I favored. They’re listed in chronological order, not from best to worst. Links are provided if I’ve reviewed the film for this site. I will post these in four installments; here is the first, taking us from 1902 to 1951:

|

#1 A Trip to the Moon/Conquest of the Pole (1902/1912) D: Georges Méliès

A double feature of shorts from the pioneer of special effects. Le voyage dans la lune (1902) provides arguably the most iconic image in fantasy cinema. À la conquête du pôle (1912) continues the exploration theme, and features an impressive encounter with a frost giant. |

|

#2 L’Inferno (1911) D: Giuseppe de Liguoro

Spectacular, and painstakingly literal, adaptation of Dante’s Inferno as Virgil guides the poet through one gorgeous, extras-torturing set after another. Available on DVD with a Tangerine Dream soundtrack. |

|

#3 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) D: Robert Wiene

German Expressionist cinema at its most nightmarish, this tale told by a madman features funhouse sets of extreme angles and painted shadows, along with influential makeup and costume design. |

|

#4 Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922) D: Benjamin Christensen

An impassioned essay film about the dangers of religious fundamentalism, Haxan also happens to give the viewer one spellbinding occult image after another, with plenty of black humor and outrageousness. |

|

#5 Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (1922) D: F.W. Murnau

Murnau was a master of silent cinema, and his unauthorized adaptation of Dracula, with images that sear the brain, delivered one of the defining cinema monsters in Max Schreck’s starch-stiff vampire. Remade by Werner Herzog in 1979. |

|

#6 The Thief of Bagdad (1924) D: Raoul Walsh

Douglas Fairbanks plays the freewheeling thief in this mega-budget spectacle of early Hollywood. The sets by William Cameron Menzies lend a storybook exaggeration to a tale that features a winged horse, a giant spider, a flying carpet, and breathtaking stunts. |

|

#7 The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) D: Lotte Reiniger

An Arabian Nights tale often cited as the earliest surviving animated feature film, Reiniger’s innovative film uses shadow-puppet-style cut-outs of intricate design to enact an elaborate fantasy romance. |

|

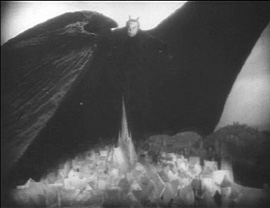

#8 Faust (1926) D: F.W. Murnau

The definitive adaptation of the Faust story is one of Murnau’s greatest achievements. Wickedly funny and tremendously entertaining, it’s a Gothic phantasmagoria of German Expressionism. |

|

#9 Metropolis (1927) D: Fritz Lang

An epic science fiction parable from another German master, Lang’s seminal work features a production design that seamlessly bridges the gap between Biblical history and a dystopian future. |

|

#10 Dracula (1931) D: Tod Browning

Though the Bela Lugosi/Tod Browning Dracula, an adaptation of a stage play of Bram Stoker’s work, is often criticized for being too talky and lacking in excitement or visual style, it is nonetheless a truly eerie work, and of course influential. The introduction to Lugosi’s Count, in a cobwebbed crypt, is indelible. |

|

#11 Chandu the Magician (1932) D: William Cameron Menzies, Marcel Varnel

If only all pulp serials and B-movies of the 30’s looked like this. William Cameron Menzies knew how to film comic book dreams. Lugosi embraces one of his best film roles as the villainous Roxor, and Edmund Lowe plays the illusionist hero Chandu. |

|

#12 Island of Lost Souls (1932) D: Erle C. Kenton

One of the creepiest horror films of the 30’s (rivaled only by Tod Browning’s Freaks), this adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau features standout performances by Charles Laughton as Moreau, Kathleen Burke as the Panther Woman, and Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law. |

|

#13 King Kong (1933) D: Ernest B. Schoedsack

One of the greatest fantasy films of all time, Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack, and Willis O’Brien breathlessly take us from a lost island overrun by dinosaurs to the summit of the Empire State Building in the tight grip of the 8th Wonder of the World. |

|

#14 The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) D: James Whale

Whale’s counterintuitive follow-up to his smash hit Frankenstein (1931) features a number of odd but poetic touches, including Dr. Pretorius’ collection of costumed homunculi in jars, and Elsa Lanchester as both the Bride and Mary Shelley herself. |

|

#15 Mad Love (1935) D: Karl Freund

Freund, who directed The Mummy (1932), combines German Expressionism and pulp drama with this adaptation of The Hands of Orlac. Peter Lorre, as a demented surgeon, is at his finest in this dream-like film. |

|

#16 Vassilisa the Beautiful (1939) D: Alexander Rou

This influential Russian fantasy was popular in its homeland during WWII, but seldom seen in the West. It’s a classic Russian fairy tale with Baba Yaga, a three-headed dragon, and a memorably surreal production design. |

|

#17 The Wizard of Oz (1939) D: Victor Fleming

Having recently rewatched this, I was struck at what a truly strange film it is to have become such a highly-regarded classic – but there’s no arguing its qualities. Dark Side of the Moon is optional. |

|

#18 Fantasia (1940) D: Norman Ferguson and others

A gamble (which didn’t exactly pay off), this film – extolling classical music – is long, ambitious, and occasionally pretentious. It’s also beautiful to behold and remains the high watermark of cel animation. Walt’s interest in his animated feature films declined after Fantasia; the films began to play it safe, which is a shame. |

|

#19 The Thief of Bagdad (1940) D: Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, Tim Whelan

A remake (of sorts) of the 1924 Thief of Bagdad, which also makes this list, this British take on Arabian Nights fantasy features a different plot and a very different lead in the young Sabu. The film was a strong influence on Ray Harryhausen as well as Disney’s Aladdin (1992). |

|

#20 The Wolf Man (1941) D: George Waggner

Universal’s horror line got a much-needed shot (or bite?) in the arm with The Wolf Man, which made Lon Chaney Jr. a star, and also offered a token role to the studio’s former leading man, Bela Lugosi. The fog-shrouded woods, the gypsy camp, and the existential angst of Chaney all add up to one of horror’s great films. |

|

#21 Cat People (1942) D: Jacques Tourneur

A Hollywood anomaly, the string of horror films by producer/writer Val Lewton for RKO counter-programmed against Universal’s monster mashes with films that emphasized atmospherics, dread, and guilt. The sophisticated and adult Cat People might be the best, though all are essential viewing. |

|

#22 Beauty and the Beast (1946) D: Jean Cocteau

Cocteau combines the visuals of a surrealist (candle-holders are human arms extending from the castle walls) with the spare precision of a modern poet. A fairy tale with teeth. |

|

#23 A Matter of Life and Death (1946) D: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

One of my “desert island films,” a Powell & Pressburger classic featuring charming performances by David Niven and Kim Hunter, trying to reconnect through the divide of the afterlife. In a reverse Wizard of Oz, Earth is presented in glorious color, and a monolithic Heaven is in stark black-and-white (because of course it is). |

|

#24 Orpheus (1950) D: Jean Cocteau

Cocteau’s masterwork, part of a trilogy filled out by the more abstract films The Blood of a Poet (1932) and The Testament of Orpheus (1960), Orpheus retells the Greek myth in a contemporary setting (cars and radios play a key role). The Underworld can be accessed by stepping through a mirror in the manner of Alice through the Looking-Glass. |

|

#25 The Tales of Hoffman (1951) D: Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger

Powell & Pressburger decided to adapt a famous opera as an opera, with only the slightest framing device (we see the theatergoers arriving, at intermission, etc.). Basically an extended version of the musical sequence of The Red Shoes (1948), the stage and the fantastic reality are seamlessly blended, evoking many stunning visual setpieces. |