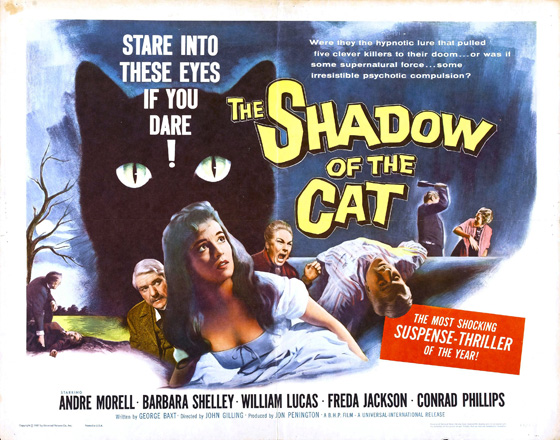

The Shadow of the Cat (1961) has long interested Hammer fans, partly for its unavailability on DVD and partly because it isn’t quite a Hammer film, being a Hammer co-production with B.H.P. Films (it went out under the B.H.P. name). That first concern has been remedied with a new DVD release on Region 2, though it essentially remains a problem film in Hammer’s filmography. Sometimes grouped with their horror output, it has little to do with Hammer’s grand guignol remakes and reinventions that marked a turning point in the genre in the late 50’s and early 60’s. It is in black-and-white, placing it more in tune with the studio’s black-and-white suspense films of the period (Scream of Fear, Paranoiac, etc.) rather than its lavish color horror films. But it possesses a good deal of true Gothic atmosphere, and coupled with its clichéd plot it is very much in line with the “Old Dark House” thrillers of the 30’s and 40’s (indeed, Hammer’s The Old Dark House of two years later pokes fun at just the sort of picture that The Shadow of the Cat unabashedly is). In short, The Shadow of the Cat is old-fashioned, and the lack of a Hammer branding may ultimately be appropriate: they didn’t typically make this kind of film.

Hammer starlet Barbara Shelley as Elizabeth.

Still, Hammer signposts are here. Barbara Shelley, who would go on to Hammer films like The Gorgon (1964) and Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), stars alongside André Morell of Hammer’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), Cash on Demand (1962), She (1965), The Plague of the Zombies (1966), and others. Freda Jackson, in a supporting role here, also appeared in the excellent The Brides of Dracula (1960). And the director is John Gilling, who would proceed with a string of solid Hammer pictures including The Plague of the Zombies and The Reptile (1966). In The Shadow of the Cat, Morell is Walter Venable, a cynical old man who marries Ella (Catherine Lacey, The Lady Vanishes) for her money, then has her draft a will bequeathing to him Duncroft Mansion (the typical Bray Studios lot). The film opens as her butler Andrew (Andrew Crawford) savagely beats her to death on the instruction of Walter. Walter buries Ella in the grounds, then proclaims to the police inspector (Alan Wheatley) that she has gone missing. But the cat knows the truth – and continues to stalk and terrify Walter, servant co-conspirators Andrew and Clara (Jackson), and soon a trio of greedy relatives, Edgar (Richard Warner, Village of the Damned), Jacob (William Lucas, Sons and Lovers), and Louise (Vanda Godsell, Sword of Sherwood Forest). These three agree to find and kill the cat on instruction of the increasingly paranoid Walter; and in their spare time, they search for Ella Venable’s second will (shades of The Grand Budapest Hotel). The cat retaliates by leading each wicked member of the household to their death. Only beautiful niece Elizabeth (Shelley) and handsome Michael Latimer (Conrad Phillips, Circus of Horrors) suspect that the cat is on a mission of revenge, and that Ella’s disappearance was actually foul play.

Murderer Walter Venable (André Morell) instructs his trusted family members (William Lucas, Vanda Godsell, Richard Warner) to capture and kill the cat.

The key setpieces are the death scenes, which typically involve Tabitha the cat leading someone into a fatal accident – drowning in a bog, falling down the stairs or off the roof, or just by scaring them to death. The audience is encouraged to root for the cat, who is actually adorable and not at all menacing, no matter how many times Gilling shoots the cat’s face in extreme close-up. Naturally, all attempts at shock are sabotaged, so the film never gets off the ground; though Gilling does his best to enliven the (fairly talky) proceedings by including shots from the cat’s POV. Most effective is the opening; Ella’s murder has a brutality that’s truly shocking by Hammer standards, given a nightmarish distortion through the cat’s eyes. This follows a vintage Gothic opening in which Ella reads from Poe’s “The Raven,” an open acknowledgement to the story’s debt to Poe (in particular the author’s oft-filmed “The Black Cat”). Though the film itself never delivers on that opening, the explicit Poe reference is interesting, given that Hammer rivals AIP and Roger Corman were at the height of their Poe series of films (Pit and the Pendulum was released the same year). So not only is this not-quite-but-almost a Hammer film, it’s also not-quite-but-almost an Edgar Allan Poe film. Gilling also finds plenty of opportunity for black humor. After Clara is killed, in the very next scene Jacob is so unmoved that he remarks to another, “Well, have they put old Clara in cold storage?” While Walter searches for Tabitha through a rat-and-cobweb-filled basement, he rants, “I’d like to brain it! I hate it!” before calmly calling out to the cat, “Kitty kitty kitty…” But damn if that cat isn’t the cutest little villain. Screenwriter George Baxt (Circus of Horrors) wanted the cat to be nothing more than a shadow – a phantom that might just exist in the head of its victims, a la “The Black Cat.” Gilling, alas, insisted upon a real cat, which removes the story’s psychological subtlety and supernatural interest. The end result is a slightly silly and very odd little picture (released on a double-bill with an undisputed Hammer classic, The Curse of the Werewolf). The new DVD, though it seems to frame the image a little too tightly, is recommended for the film’s rarity as well as the inclusion of an excellent, surprisingly in-depth documentary about the film directed by Hammer expert Marcus Hearn.