Monday, November 19th, 1990, all anyone could talk about in my high school cafeteria was Part I of Stephen King’s “It” (1990), which had aired the night before: the wounds in our psyche were fresh. A well-publicized two-part “Television Event” on ABC, the film boasted high production values, your typical miniseries all-star cast, and an envelope-pushing sensibility that makes one wonder just how it got on TV in the first place. This is, after all, an adaptation of a Stephen King novel about a child killer, and not just that: a child-killing demon clown. But it was a bestseller, and it was Stephen King – America’s most popular living author – so ABC took the risk, and a generation of young ones were scarred for life. I was 14, too old for scarring, but I was immediately absorbed in Part I, connected deeply to the tale of the “Losers Club,” and mesmerized by Tim Curry’s performance as Pennywise the Clown, who ends each cheery monologue with the reveal of yellow, razor-sharp teeth. Every shock from the first two hours was recounted with gleeful detail over our bag lunches. We had to wait until Tuesday night before we could see the conclusion, wondering how the grown-up Losers Club was going to kill Pennywise, who seemed to be, in his true form down in the sewers of Derry, some strange glowing entity. But the talk at the Wednesday lunch was bitter – our first burst of disillusionment. “It was just a stupid spider,” my friends said. Pennywise was supposed to be more. Something, of course, no made-for-TV miniseries could ever properly capture: pure, abstract Fear. I doubt we knew the solution to this problem. Maybe we just wanted to see the kids from Derry fight an evil clown with magical powers, or maybe we were getting a first lesson that sometimes anticipation can be so exciting that nothing can ever properly satisfy it. Part II wasn’t bad, but as far as my cafeteria table was concerned, it was The Phantom Menace. I was indifferent to the spider. I recall offering the defense stated in the show, that the Loser Club could never see Pennywise’s real form because their minds couldn’t take it, therefore it wasn’t really a spider…but my friends would have none of it. I was supposed to hate it. I rode the bus home thinking, “What would’ve worked better than a spider?” What you don’t know is that I wrote stories for my cafeteria table. I made them comic books, and they followed every issue. I was trying to figure out how to make storytelling work. The spider in It was a problem I felt I had to solve, never mind that the show had aired and it was done. How could such a great setup lead to a climax that disappointed so many people? Why couldn’t they stick the landing?

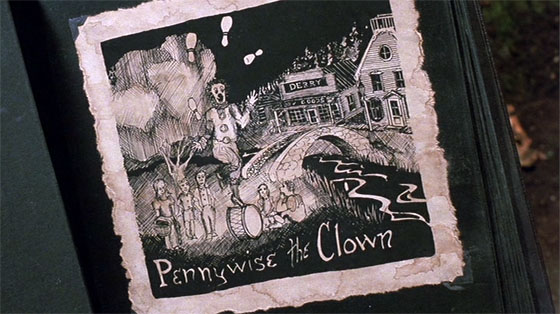

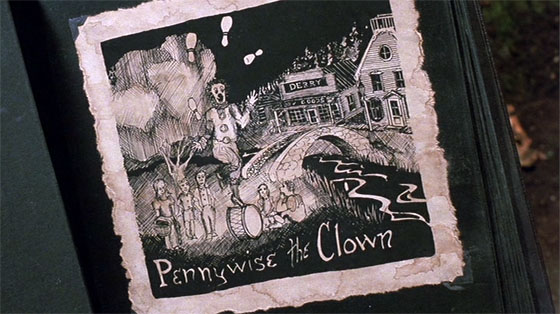

When Georgie loses his newspaper boat to a sewer, helpful Pennywise the Clown (Tim Curry) promises him that “everything floats down here.”

I taped Stephen King’s “It” when it aired, and watched it a few times as I struggled through my high school years. Like the characters in the film, I’d forgotten…but revisiting the film decades later, it’s evident that the film must have spoken to me, because I knew it well enough that I could finish its sentences. And it’s obvious to me why I connected so much with the film (not enough to read the book, apparently – I still haven’t gotten around to that). In It, the present collides with the past as a rash of child-murders and disappearances resume in Derry, Maine, exactly 30 years after the last time such events occurred. Librarian Mike (Tim Reid, WKRP in Cincinnati) knows the truth, and makes calls to those who share the secret. They’re the fellow members of his high school’s self-proclaimed “Losers Club,” social outcasts all: Bill (Richard Thomas, The Waltons), who stuttered; Ben (John Ritter, Three’s Company), who was obese; Beverly (Annette O’Toole, Cat People), who suffered from an abusive father; Richie (Harry Anderson, Night Court), who was the class clown with taped glasses; Eddie (Dennis Christopher, Breaking Away), who was a diminutive asthmatic; and Stan (Richard Masur, The Thing), who’s Jewish. In 1960 they dodged bullies – led by the sadistic Henry Bowers (played in the present by Michael Cole of The Mod Squad) – but also battled the evil entity Pennywise, who most frequently takes the form of a circus clown, but can become anything the kids dread, including, at one point, the werewolf from I Was a Teenage Werewolf, after the gang takes in a screening. (Sadly, Michael Landon doesn’t provide a cameo.) To Bill, the battle with Pennywise is personal, because the demon killed his younger brother Georgie by luring him into a gutter drain. They boldly confront Pennywise in the sewers where he dwells, fighting him with that which they have faith can harm him – Eddie believes his asthma breather is battery acid; Beverly believes that silver can be as effective as it is on a werewolf – and with the clown-demon in retreat, they come to think the curse on Derry has been lifted. Gradually their memories of Pennywise become clouded over, until the night Mike phones them. Many are enjoying successful careers: Bill is a horror author (looking quite a bit like Garth Marenghi), Richie is a TV comic, Ben has lost weight and become a wealthy architect, Beverly is a fashion designer. But as soon as they hear Mike’s voice, memories of Pennywise flood back. Old habits return, such as Bill’s paralyzing stutter. They’re like terrified kids again, about to face the worst possible bully.

The Losers Club: Beverly (Emily Perkins), Richie (Seth Green), Ben (Brandon Crane), Mike (Marlon Taylor), Bill (Jonathan Brandis), Stan (Ben Heller), and Eddie (Adam Faraizl).

Although the film apparently skips over quite a bit, and leaves out some of the novel’s more outlandish or controversial elements, it holds up well these twenty-four years later, enough for me to say that it’s one of the finer films to emerge from King’s hefty bibliography. Despite a dated and kitschy score (which won an Emmy, so what do I know), the performances are almost universally fantastic, elevating this miniseries in an era that no one ever pointed to as a “golden age of television.” The child actors are perfectly cast, and include Seth Green, later of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Robot Chicken, and more; Emily Perkins, who would co-star in the Ginger Snaps films; and Jonathan Brandis of TV’s SeaQuest DSV, who sadly committed suicide in 2003. Brandis and Perkins in particular are dead ringers for the actors playing their adult counterparts (Thomas and O’Toole, respectively), lending a certain continuity to the extended flashbacks which interrupt the present. Credit must also be given to director Tommy Lee Wallace, who directed the underrated and fascinating Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) – a film that also featured children getting slaughtered (maybe it got him the job?). By committing to such young actors – rather than the twenty-something high schoolers of Beverly Hills, 90210, launched the same year – Wallace actually ups the fear ante, because these characters seem genuinely vulnerable. The scene in which Little Eddie gets attacked by the gym shower nozzles wouldn’t have quite the same effect if he weren’t such a scrawny little tyke. When Beverly is seized by Henry Bowers and his greaser gang, we get an excruciating close-up while his fingers squeeze her lips together, and his face, smiling with menace, moves uncomfortably near. She isn’t some sexualized American Pie high schooler. She’s a little girl in serious danger of being beaten or sexually assaulted. (Wallace also guarantees there’s plenty of blood on display in this TV-movie, and maybe he gets away with it because it’s indirect bloodshed: exploding out of popped balloons from Pennywise or spurting from the plumbing in young Beverly’s bathroom. At the time I had never seen so much blood on a television program, though it’s probably tame by modern CSI standards.)

John Ritter, Annette O’Toole, Richard Thomas, and Dennis Christopher descend into the sewers to face It.

My cafeteria table was correct in praising the first part over the second: Part I is beautifully structured and almost suffocating in its relentlessness. On the surface, nothing much happens in Part I, at least in present-day 1990. Mike calls each of his childhood friends and asks them to deliver on their promise to return to Derry when “It” returned; the rest is handled in flashbacks of 1960, a childhood of negotiating neglectful or abusive parents at home and cruelty and sadism at school, enjoying brief windows of pleasure like attending a matinee screening of a monster movie, or cracking a joke that makes a crowd of schoolkids laugh (beep-beep, Richie), or that pretty girl in class saying something nice to you. Pennywise, for all of Tim Curry’s scenery-chewing (he’s excused: if ever there was a role that allowed for it…), hardly seems supernatural at all in a childhood so overflowing with misery and menace: he’s simply inevitable. And as I watched this it struck me: when I first watched this movie, I was a freshman in high school and I was getting bullied every day. I had my little windows of pleasure, giving comic books to friends, trying to make people laugh, coming home and watching movies: but I also dreaded and did anything to avoid the public shower of the high school gym (like Eddie), tried not to make eye contact with certain people on the bus who would give me a hard time, and tried to stay out of fights. I was new to high school and hating it so far. Then, a few months into my prison sentence, It came along, and it was as though I was part of the Losers Club, fighting Pennywise. Of course I watched my VHS tapes over and over. And of course I still hate clowns.

Pennywise attacks.

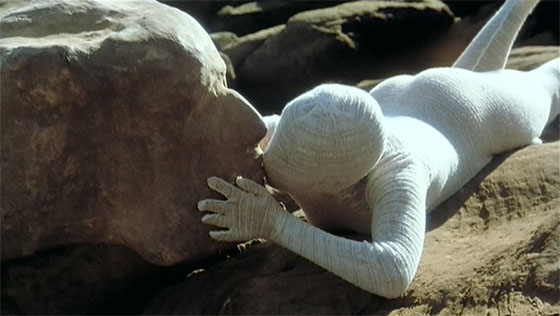

Finally, as to that spider. It’s stop-motion, at the very end of an era in which such things were permissible. Soon it would be Jurassic Park and CG everything. The spider, to the modern viewer, is charming. I’m a Ray Harryhausen fan; of course I like the damn spider. But an audience told that Pennywise can be their worst nightmare, the very worst thing they can possibly imagine, does not want a big spider. I am not sure there is any proper solution to this except to focus on the characters and the climax of their journey as an absolution of their traumatized pasts. Here is where It actually stumbles: the climax of Part II is rushed and too separate from what the audience cares about. Richard Thomas’s Bill races to save his wife, Audra (Olivia Hussey, Romeo and Juliet), who’s coccooned with the spider’s other victims. But we don’t care about Audra, who’s hardly been in the film at all. We care about the Losers Club. Since the audience is not properly prepared for a spider, the imagery of cobwebbed victims and green-pulsating abdomens and the spider’s heart – they pile onto the creature and tear out its heart – feels like the ending of some other, cheaper horror film. To be honest, none of this bothers me too much. This is the rare film that deserves to be remade, because I think that kids should see it (or sneak into it, because their parents won’t let them go). Guillermo del Toro once expressed an interest, and I hope he eventually makes room in his schedule. Kids should have their own It. Many already do, actually, and they’re fighting it every day – but horror allows them to see it. And that’s a tool; that helps you destroy your fears.