Watching David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986) is a momentous event for me. Some background is required. When I was little, my parents enforced a strict “no R-rated movies” policy. But I was keenly interested in monsters. From the library I checked out binders of Famous Monsters of Filmland, and read many books on classic monster movies. Lon Chaneys Sr. and Jr., Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff were all names with which I was familiar from a very young age. Because I had no access to more modern, gorier horror films like Alien, I was educated on the classic Universal horror movies of the 30’s and 40’s, and giant monster movies of the 50’s and 60’s. I was certainly familiar with The Fly (1958) starring David Hedison and Vincent Price, though before I actually saw it, I remember my mother describing it to me. “And then there he is,” she said, “stuck in a spider’s web, a fly with a human face. A spider is about to eat him. And the little fly is saying ‘Help me, help me!'” (Oh – spoilers.) I know she described the scene to me before I saw it because I anticipated that climax on my first viewing. All I remember is waiting for that horrifying moment, which carried such weight because my mother was often imitating the little David Hedison voice, “Help me! Help me!” while wriggling her fingers like little fly legs.

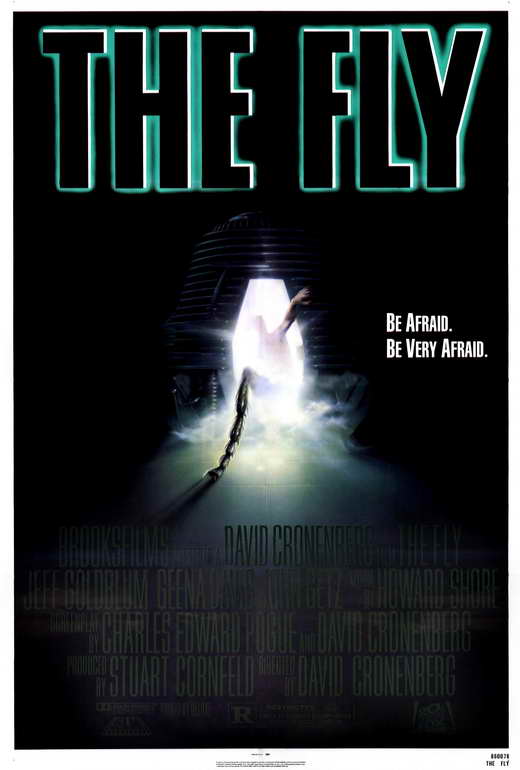

David Cronenberg’s “The Fly.”

When I was about ten years old, my father rented David Cronenberg’s The Fly. After I went to bed he watched it with a family friend, Jinx; my mother declined because she can’t stand horror movies (this, the same woman who chased me about the house squealing “Help me, help me!”). The next evening I was eating my favorite meal, Campbell’s Split Pea Soup, a lovely viscous green. Jinx is delighting in describing to my horrified mother every scene from Cronenberg’s film. Finally she says, “And he just vomits. He vomits and – it looked like that.” She pointed at my soup. Everyone laughed, expecting me to be traumatized. Perhaps this, at last, would turn young Jeff off Campbell’s Split Pea Soup. But, in truth, I was put off only for a moment. To this day, I love Campbell’s Split Pea Soup. Anyway, come high school, come R-rated movies, I still don’t watch Cronenberg’s The Fly. It just never crosses my path. In college, I finally rent the film, but I never get around to watching it, and I have to return it before it’s overdue. A couple weeks ago, I was up at three in the morning trying to get a crying baby to fall asleep. I start watching The Fly on the Sundance Channel. I’m halfway in when I realize that the film is edited, the swearing awkwardly dubbed over, the violence snipped out. (It had been a while since I watched this channel. Since when did they start editing their movies? Why would anyone watch this channel anymore?) I have to stop watching. I’m a purist. But now I’m resolved: I am going to watch this movie. This last weekend, I picked up a used copy of The Fly and The Fly II from the same store. “Ooh,” said the woman behind the counter, and she had to sing the next two words, for some reason: “The Fly“…as though I were about to be initiated into a special cult. Now I am here to report that I have finally watched the damn movie, uncut, all the way through, pea soup vomit and all.

Geena Davis as Veronica Quaife.

The thing about watching it now is that I have context galore. I’m already familiar with not just the Price film and its immediate sequel, Return of the Fly (1959), but also the original story “The Fly” by George Langelaan, and most of Cronenberg’s work – which is probably more important when it comes to watching this particular movie. (I’m embarrassed to admit I had no idea that 1965’s The Curse of the Fly existed until a couple weeks ago, so I’ll have to track that down for completeness’ sake.) The story is almost like an ancient fable to me by now, something Aesop wrote on a bender. A scientist builds two teleporter pods. A fly slips in beside him just before he zaps himself from one pod to the next, and when he emerges from the other end, he’s part-fly. In the original story and the 1958 film, the fly has also become part-him. He lumbers around with a fly’s head and his left arm swapped out for a fly’s leg, and the fly buzzing around the house has his head and arm. But Cronenberg and co-screenwriter Charles Edward Pogue (Psycho III) tweak the concept to avoid the “Help me, help me!” twist ending and plunge into even darker territory. Scientist Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) is genetically spliced with the fly – they are fused together and become one, leaving no little fly with a Goldblum face. At first nothing seems to have gone wrong at all. If anything, he becomes reinvigorated and more physically and sexually athletic than ever before – even acrobatic. But soon enough the fly inside him begins to poke through, which Cronenberg depicts, in his typical body-horror fashion, as a tumorous full-body mutation and a grotesque evolution.

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) begins to transform.

It’s often about evolution with Cronenberg: homo sapiens moving to the next, unexpected branch on the tree, which can seem frightening and repulsive because it’s unfamiliar and new. Sometimes that next stage is envisioned as a merging with technology (see: Videodrome, eXistenZ; even the J.G. Ballard adaptation Crash plays with the theme), and that pops up in The Fly in a few different ways. Brundle is using the telepods to deconstruct and reassemble matter, but at first is limited to inanimate objects, struggling to teach the computer how to handle the “madness” of the flesh. How he does this isn’t made specific. He taps at some keys, and a computer monitor displays 80’s computer gobbledygook. But he is finally able to pass beyond his early, failed experiment with a baboon, which turned it inside-out (good God, why not use mice?!). Drunk one night, jealous that his new sexual partner and scientific chronicler, journalist Veronica Quaife (Geena Davis), might be stepping out on him with her obnoxious editor and ex-boyfriend Stathis Borans (John Getz, Blood Simple), he “passes through,” as he puts it, unaware that a fly is in the pod with him. Afterward, his body seems to surge with new energy before an apparent physical deterioration starts to take place. Nonetheless, he is born again, and evangelical about it. This leads to one of the most Cronenbergian monologues in the director’s filmography:

You’re afraid to dive into the plasma pool, aren’t you? You’re afraid to be destroyed and recreated, aren’t you? I’ll bet you think that you woke me up about the flesh, don’t you? But you only know society’s straight line about the flesh. You can’t penetrate beyond society’s sick, gray, fear of the flesh. Drink deep, or taste not, the plasma spring! You see what I’m saying? And I’m not just talking about sex and penetration. I’m talking about penetration beyond the veil of the flesh! A deep penetrating dive into the plasma pool!

As Max said in Videodrome, “Long live the new flesh!” But this new flesh – which eventually does drop off “Brundlefly” like the deep-fried skin of an onion ring – is obligated to technology. His final transformation in fact involves a horrific merging with the telepod itself, the ribcage-like exterior of the pod fusing with his spine.

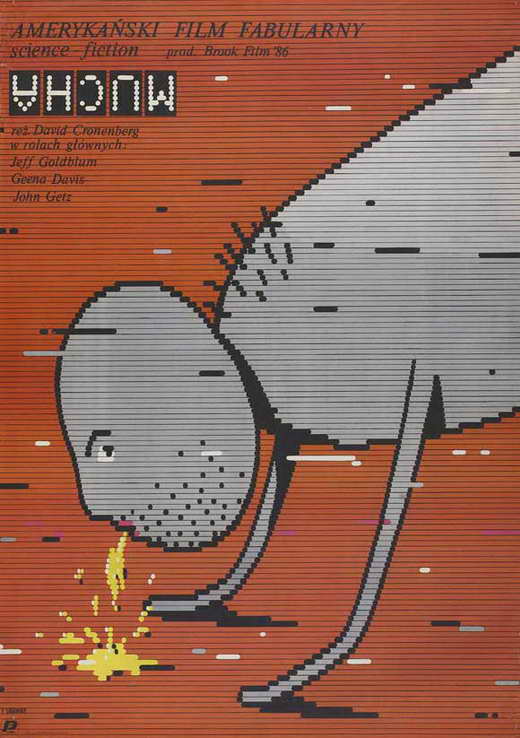

The Polish poster for “The Fly” emphasizes what’s really important: vomit. Also note that Brundle hasn’t shaved in a while.

It is equally important what he is turning into: “Brundlefly” is losing his humanity at a rapid rate, more and more becoming the insect. This is Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” as a horror movie; if Gregor Samsa’s insect was recognizably human, Seth Brundle’s reveals a ruthless, amoral, animal instinct that may lurk beneath every man’s flesh. Brundle’s insectoid impulses drive him to cheat on Veronica with a barfly (joke intentional on Cronenberg’s part?) after “winning” her in a physical contest against another man, an arm wrestling match for the ages. When he finally confronts Stathis in his torn-to-pieces apartment, methodically mutilating him, it’s an expression of his jealousy toward his nemesis – manifested in acidic puke. The relationship between Brundle and Veronica is the heart of the film, and the performances by Goldblum and Davis (a real-life couple for a while, and who have genuine on-screen chemistry) are key to the film working as well as it does. At one point, Brundle warns her that if she sticks around, he’ll hurt her. He won’t be able to help himself. It wouldn’t be a stretch to read the film as the downward spiral of a relationship that culminates in physical abuse. Central to this reading is a scene in which Brundle tries to force Veronica into the pod, urging her to become like him; he resents it when she refuses. Eventually, in the film’s climax, he does force her into the pod, and by now he has revealed what he truly is: an insect, a monstrous wall-crawling fly with hardly any traces of the human on display. But he’s also the funhouse mirror image of an abusive father. Veronica has become pregnant, and though she wants an abortion, he wants to fuse them all together, partly in an attempt to purge some of the fly out of him and recover his humanity, but also to become a nuclear family: “We’ll be the ultimate family. A family of three joined together in one body. More human than I am alone.”

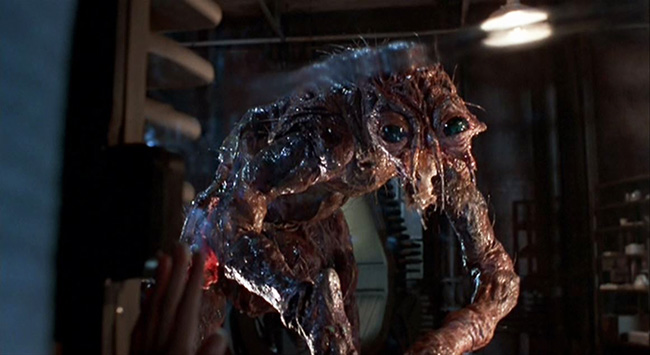

The flesh fallen away, the transformation complete.

No mistake, The Fly is a strange film. It’s a Hollywood blockbuster from an auteur horror director; he had initially come to Hollywood to make Total Recall, but found more potential to express his pet interests in this 50’s B-movie remake. The first half of the film is charming as hell, completely investing the audience in the budding romance between Goldblum and Davis and the drama of Brundle’s scientific experiments. Then Cronenberg slowly shifts the tone into grand guignol. Toward the end of the film, he even cameos as an abortion doctor in a ludicrous gross-out dream sequence where he delivers a giant larva from between Davis’ legs. This is the style of black humor that The Fly possesses in spades. It’s a monster movie that gleefully sends up its own concept – Goldblum vomits, vomits, vomits, because that’s what flies do to digest, you see? – but it has more on its mind. It’s a tragedy, and like all tragedies, it’s all about guiding the audience toward the inevitable downbeat ending that everyone can see coming. Brundle’s not going to get his old flesh back. Once it has begun to boil, fester, and split apart, all that’s left is the macabre fascination with what he might look like underneath it all.

So what did I think, after a lifetime’s worth of anticipation? Naturally there was a certain disappointment; a part of me, I think, would rather never have seen it, since it couldn’t possibly have lived up to such expectations. No movie could. I wouldn’t rank it toward the top of Cronenberg’s films, yet it’s satisfying to see him flex his intellectual obsessions on a Hollywood budget, with a simple sci-fi plot on which he could hang whatever he liked. Like the Brundlefly, it’s a very unique hybrid. And my wife marveled that I grabbed a bite to eat while watching it. “How can you eat?” she said. At least it wasn’t split pea soup.

Up next: The Fly II!