Welcome back to Midnight Video, the video store I opened in my basement! Here are some of our latest titles (which you can’t rent, because I keep the house locked).

The Sword and the Sorcerer

New Arrivals

I’ve written about The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982) at length before, but it’s been quite some time since it’s been available on disc. Shout Factory compensates for the gap with a surprising 4K UHD + Blu-ray upgrade, replete with a limited edition poster, a 4K scan of the film from the original negative, a new audio commentary from director Albert Pyun, and in-depth interviews. This is a film cursed to never be as good as you remember it, but it does have its qualities, and it’s certainly a notch or two better than the many Roger Corman-produced pulp fantasy films that glutted the market in the 80’s (and which I love, if shamelessly). TV actor Lee Horsley received a rare starring role as Talon, a prince-turned-mercenary wielding a three-bladed sword, and he’s very well cast here, bringing some much-needed charisma to a character who’s actually quite the sleaze. Also well-suited to his role is sneering Richard Lynch (Deathsport) as the tyrant “Cromwell” (not Oliver Cromwell, so far as I can tell), who seizes the throne through the magic of a literally slimy demon sorcerer. The supporting cast includes more TV veterans: Kathleen Beller (Dynasty), Richard Moll (Night Court), and Joe Regalbuto (Murphy Brown). This was the first film from director Pyun, who would go on to a diverse array of genre films including Radioactive Dreams (1985), Vicious Lips (1986), Alien from L.A. (1988), Cyborg (1989), Dollman (1991), and many others.

A low-budget production that became an unexpected box office hit – no doubt in part because of its terrific poster – The Sword and the Sorcerer offers flashes of potential throughout, but they remain only brief flashes. Most of the film seems to be spent setting up the plot, and it only really cuts loose in a swashbuckling scene in which Horsley swings and swordfights from one corner of the palace to the other, at one point barging into a chamber of nude harem girls and stealing a kiss between sword-swings. There are some funny lines and moments, as well as atmospheric cinematography and sets – the 4K really packs its punch in the film’s deep blacks and reds that occasionally evoke the paperback covers of Frank Frazetta – but the film rushes to its conclusion just as things are getting going, promising a sequel, Buckaroo Bonzai-style, before rolling credits. The extras are revealing, with Pyun (who is now battling dementia) discussing his battle for control of the film with producer Brandon Chase, how he nearly quit the set, and how he was shut out of the editing room. He wanted to lean harder into more stylized violence, noting the Lone Wolf and Cub films as an influence. Beller explains that she’d hoped the film would be more comedic and fun, a la Raiders of the Lost Ark – in fact, her Karen Allen-esque performance is one of the film’s redeeming qualities. She also notes Pyun’s kindness but obvious inexperience, and begrudgingly admits, when she recently watched the film for the first time since its release, that it wasn’t quite as bad as she’d long believed. Yet, clearly, it could have been so much more.

Communion

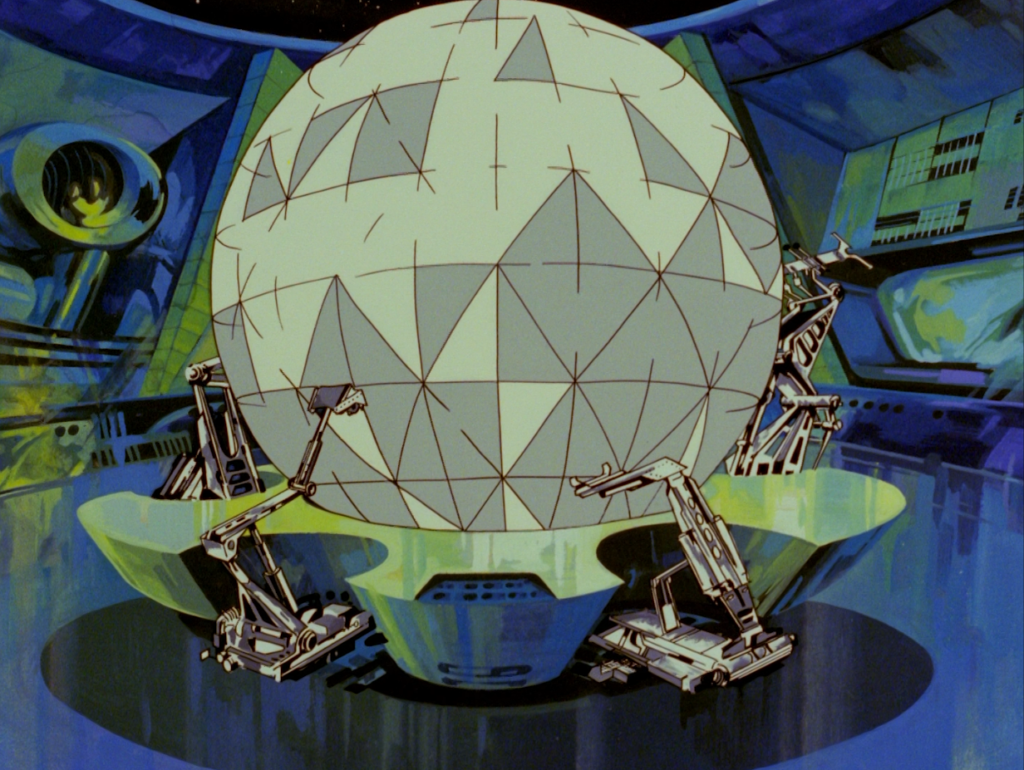

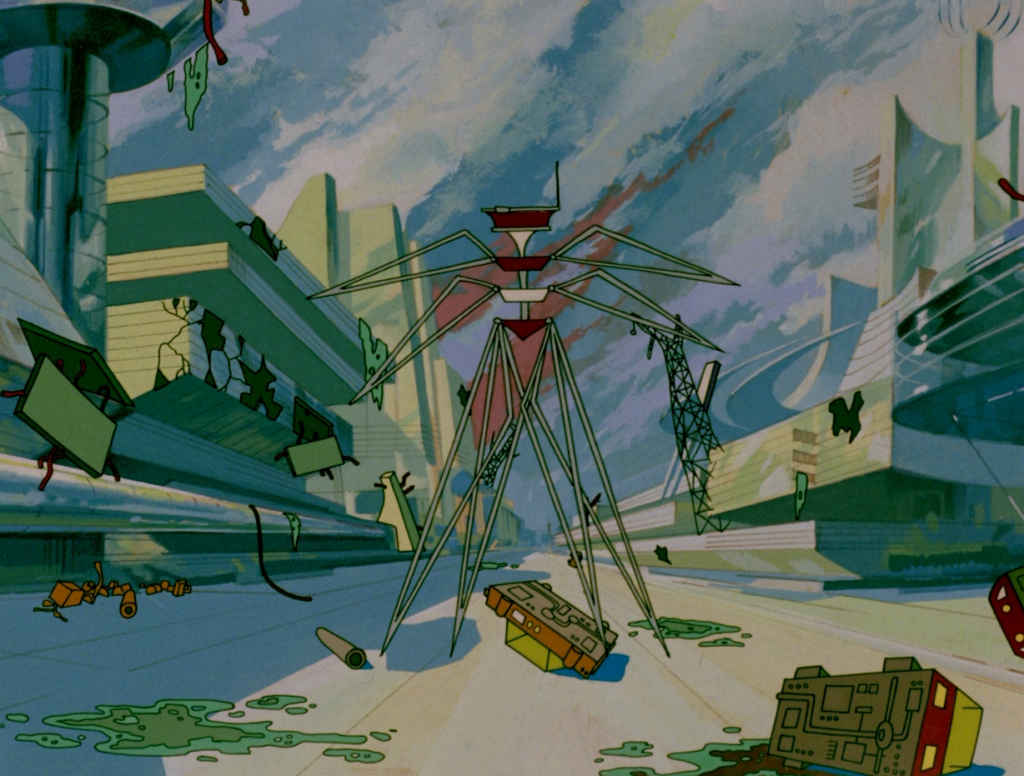

Also new from Shout is Communion (1989) starring Christopher Walken, Philippe Mora’s adaptation of Whitley Strieber’s bestseller in which he claimed to have had an extraterrestrial encounter. It’s easy to see why this is one of Shout’s limited edition releases, exclusive to their website (and apparently 75% sold out already): it’s a very soft-looking HD transfer, lacking in detail and badly in need of a new restoration. Nonetheless, the disc ports over some valuable older features including a commentary track by Mora and William J. Birnes, the publisher of UFO Magazine, as well as outtakes and behind-the-scenes footage. And this is one weird-ass film that’s worth revisiting. Much like Mark Pellington’s underrated The Mothman Prophecies (2002), or – more relevantly – the alien abduction film Fire in the Sky (1993), Communion attempts to build credibility for its “true” story by creating intense and unnerving depictions of paranormal encounters. And, smartly, it leans into skepticism. As Mora describes on the commentary track, he’s not quite a believer himself, and neither was Walken. Working from Strieber’s own screenplay, the filmmaker avoids building this into some Close Encounters of the Third Kind faith redemption story, and there’s no giant spaceship to display in the climax. Instead, Strieber (Walken), his wife (House of Games‘ Lindsay Crouse) and their son remain shaken and perplexed even by the film’s end. (Since Strieber didn’t get carried away by a UFO, the narrative resolution is nothing more than, “And so he wrote a book about it.”) The film seems to acknowledge that the viewer may already believe that Strieber – a horror novelist (he wrote The Hunger) who gained his greatest fame with the book Communion – is the perpetrator of a hoax. But the film is effective at shifting the conversation from “nothing happened” to “something happened, but we can never know what.”

What’s so intriguing about Communion, especially viewed post X-Files, is that it doesn’t shy from the sheer unbelievability and strangeness – even silliness – of so many accounts of alien encounters, abductions and rectal probes. The insectoid grays have a rubbery face and elastic arms, wobbling about and dancing on a table like a cheap sideshow attraction. Troll-like bluish creatures with massive faces – at one point likened to kobolds of legend – are depicted in a completely different style of creature design, more detailed but absurd in their own way, pursing their lips and flexing their mouths, and they share space with the wiggling grays. At one point, Walken dances with them, high-fives them, dons an alien mask, and even kisses them on the lips. It’s ridiculous, and it’s supposed to be. When Walken is pressed by his friends to describe what he’s seen, he can’t stop laughing – though the laughter is increasingly hysterical as the story progresses (Walken’s in his wheelhouse, you can be certain). He’s uncomfortable attending a support group of fellow abductees, and maintains an antagonistic relationship with the hypnotherapist (Frances Sternhagen) who only uncovers details that are more disturbing and bizarre than enlightening. At one point, Walken tears at the face of an alien and sees that it’s just a mask for something more frightening underneath. But that too, he says, is just another mask. The value of Communion is presenting a story in which the truth is never even approached; it just grazes us, blinds us, like the lights of a UFO as it sears through the sky.

Morvern Callar

Fun City Editions, a partner label of Vinegar Syndrome, recently released a much-needed Blu-ray upgrade (a 2K scan of the interpositive) of Morvern Callar (2002), one of the very best indie films of the 2000’s. Directed by Lynne Ramsay (We Need to Talk About Kevin) and starring a young Samantha Morton (Minority Report), this adaptation of the 1995 novel by Alan Warner follows the titular character, a Scottish woman who, in the opening scene, has just discovered that her boyfriend has committed suicide. Rather than reporting the death, she keeps the body where it is, taking the mixtape he left her and his unpublished manuscript. Impulsively she decides to take credit for the novel, sending it to a publisher and receiving a surprising positive response. After slicing up her boyfriend’s body and burying it in the highlands, she withdraws his cash and invites her supermarket co-worker (Kathleen McDermott) to a resort in Spain for drunken partying and hook-ups. But Morvern remains disconnected all the while, seldom removing her headphones while she listens to the mixtape (and thus providing the film’s amazing soundtrack, which includes the Velvet Underground, Can, Stereolab, Broadcast, Aphex Twin, and the Mamas and the Papas). Increasingly isolated, she continues to shed her attachments in pursuit of some undefined future and freedom. Ramsay shoots Morton like she’s observing some creature from another world, Morvern’s unpredictable behavior and mysteriously naïve smile leaving her enigmatic to the end. It’s an intensely subjective film which, by design, never quite untangles its riddle of a subject. And it’s also darkly funny, particularly when Morvern finally meets up with her eager publishers. When they ask her what she’s planning to write next, Morvern, who has never even read the novel they’re discussing, replies with an irreconcilable mix of impishness and genuine confusion, “I work in a supermarket.”